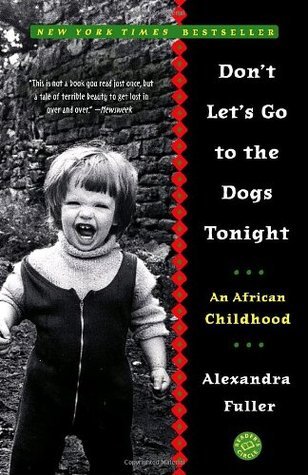

| Title | : | Dont Lets Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 315 |

| Publication | : | First published December 1, 2001 |

| Awards | : | Guardian First Book Award (2002), Book Sense Book of the Year Award Adult Nonfiction (2003), Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize (2002) |

Dont Lets Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Reviews

-

This is one of my top-ten favorite books of all time. An extremely compelling memoir, well-written, poignant but not maudlin or precious. I've read it twice and feel another reread coming on.

The brutal honesty in this story is startling, and Fuller does not set out to insert political or social critique into her story. This is probably unsettling for readers who come face-to-face with her family's colonialist attitudes and expect to hear her criticize and critique them. However, I prefer that Fuller let the story stand on its own. The book doesn't set out to dissect "Issues," but rather to tell one particular- and it is a particularly heartbreaking, frightening, disturbing, visceral, and funny one- story. -

I almost gave this book four stars because it was very well-written and evocative. But I just never felt much of a connection to the book or to any of the characters. The author's writing skill made it a pleasant enough read - at least, pleasant enough to finish. But it definitely wasn't a can't-put-it-down kind of book.

If I had to give concrete criticisms of the book, the main one would be that she doesn't develop any characters outside of her immediately family (in fact, it seemed her family didn't have any substantial relationships with anyone, other than each other), and even those characters could use a bit more context. (Why were they in Africa? I mean, what really motivated them to keep slogging it out in Africa, really? Where did their racism come from? How did she feel about their racism? How did her parents meet and what ties did either of them have to Africa before deciding to raise their kids there? What motivated them to raise children in a country in which a civil war was raging?)

On the other hand, she writes terrific dialogue and her sensory descriptions of Africa made me feel like I was there. -

The memoirs of the childhood of a white girl (Alexandra, known as Bobo), raised on African farms in the 1970s and 1980s, along with her sister, Van(essa). But it's not a gilded, ex-pat life: her parents lose their farm in forced land distribution, after which they are itinerant farm managers, who move where the work is, often to disease-ridden and war-torn areas. They also have their own problems with bereavement and alcohol. It is perhaps closer to misery lit, although the tone is mostly light, and the worst episodes glossed over.

It is told in a chatty and slightly childish and rambling style (she is a child for most of the book), mostly in the present tense. This means the precise sequence of events is not always clear, but overall, it is an endearing insight into some troubled lives and times. It does rather fizzle out at the end, though.

QUOTIDIAN DANGER

The opening is a startling demonstration of how mundane life-threatening danger can become. "Mum says, 'Don't come creeping into our room at night.' They sleep with loaded guns beside them... 'Why not?' 'We might shoot you.'" Not very reassuring to a small child who might want a parent at night. By the age of 5, all children are taught to handle a gun and shoot to kill. There are many more examples throughout the book. For instance, the parents buy a mine-proofed Land Rover with a siren "to scare terrorists", but actually its only use is "to announce their arrival at parties". At the airport, "officials wave their guns at me, casually hostile".

IDENTITY AND NOT BELONGING

The Fullers are white and apparently upper middle class, but heavily in debt (though they manage to pay school fees). Mum says "We have breeding... which is better than having money", and they're pretty bad at managing what little money they do have. Often, they live in homes that are really dilapidated and lacking basic facilities.

Bobo feels neither African (where she spends most of her childhood) nor British (where she was born). At a mixed race primary school, she is teased for being sunburnt and asked "Where are you from originally?" and when at a white school that then admits African children, learns what it is like to be excluded by language (they talk Shona to each other). She is also very aware of her family's thick lips, contrasting with their pale skin and blonde hair.

RACE

One aspect that some have objected to is the attitude and language relating to the Africans. However, as I read it, Fuller is merely describing how things really were: casual, and sometimes benevolent racism were the norm.

As a small child, she resists punishment by saying "Then I'll fire you", which is awful, but reflects a degree of truth, and similarly, her disgust at using a cup that might have been used by an African is a learned reaction. However, as she grows older and more questioning, it's clear she is no racist.

It would be very sad if fear of offence made it impossible to describe the past honestly, though the list of terms by which white Rhodesians referred to black ones might be unnecessary.

I suppose you could argue she should have done more to challenge the views around her, such as when Mum is bemoaning the fact that she wants just one country in Africa to stay white-run, but she was only a child at this point.

In her parents' defence, they treated their African staff pretty well, including providing free first aid help, despite the fact they were so short of money they had to pawn Mum's jewellery to buy seed each year, then claim it back if the harvest was good. "When our tobacco sells well, we are rich for a day." Only a day.

What to make of an observation like this? "Africans whose hatred reflects the sun like a mirror into our faces, impossible to ignore."

There is beautifully written passage describing driving through a European settlement and then Tribal Trust Lands: "there are flowering shrubs and trees... planted at picturesque intervals. The verges of the road have been mown to reveal neat, upright barbed-wire fencing and fields of army-straight tobacco... or placidly grazing cattle shiny and plump with sweet pasture. In contrast, the tribal lands "are blown clear of vegetation. Spiky euphorbia hedges which bleed poisonous, burning milk when their stems are broken poke greenly out of otherwise barren, worn soil. The schools wear the blank faces of war buildings, their windows blown blind by rocks or guns or mortars. Their plaster is an acne of bullet marks. The huts and small houses crouch open and vulnerable... Children and chickens and dos scratch in the red, raw soil and stare at us as we drive thought their open, eroding lives." Those are not the words of a racist.

DEPRESSION, TRAUMA, ALCOHOLISM

There are some very dark episodes (including deaths), and at one point, even the dogs are depressed, and yet the book itself is not depressing. For instance, the four stages of Mum's drunken behaviour in front of visitors is treated humourously.

More troublingly, a victim of a sexual assault is just told not to exaggerate, and the whole thing brushed away. There is equally casual acceptance of the children smoking and drinking from a young age.

There is fun, but also a lack of overt love, particularly touching (the many dogs are far luckier in this respect!); aged only 7, Bobo notes "Mum hardly even lets me hold her hand". That is a legacy of multiple hurt and grief - and the consequent problems.

Then there is a life-changing tragedy, for which Bobo feels responsible: "My life is sliced in half". Afterwards, "Mum and Dad's joyful careless embrace of life is sucked away, like water swirling down a drain."

A later tragedy has more severe consequences, and these passages are described more painfully:

* "In the morning, when she's just on the pills, she's very sleepy and calm and slow and deliberate, like someone who isn't sure where her body ends and the world starts."

* "When Mum is drugged and sad and singing... it is a contained, soggy madness" but then "it starts to get hard for me to know mere Mum's madness ends and the world's madness begins."

* "She hardly bothers to blink, it's as if she's a fish in the dry season, in the dried-up bottom of a cracking river bed, waiting for rain to come and bring her to life."

* "Mum smiles, but... it's a slipping and damp thing she's doing with her lips which looks as much as if she's lost control of her mouth as anything else."

* "Her sentences and thoughts are interrupted by the cries of her dead babies."

* "To leave a child in an unmarked grave is asking for trouble."

* She is grieving "with her mind (which is unhinged) and her body (which is alarming and leaking)".

OTHER QUOTATIONS

* A new home "held a green-leafy lie of prosperity in its jewelled fist".

* When they stop a journey at a fancy hotels, the opulence is unfamiliar: "the chairs were swallowingly soft".

* "The first rains... were still deciding what sort of season to create."

* "It is so hot outside that the flamboyant tree outside cracks to itself, as if already anticipating how it will feel to be on fire... swollen clouds scrape purple fat bellies on the tops of the surrounding hills."

* Captured wild cattle give "reluctant milk" and even after adding Milo milkshake powder, "nothing can disguise the taste of the reluctant milk".

* A German aid worker "is keen on saving the environment, which, until then, I had not noticed needed saving".

* The ex-pat lives were typically "extra-marital, almost-incestuous affairs bred from heat and boredom and drink." When they go to England for good, they remember Africa with "a fondness born of distance and the tangy reminder of a gin-and-tonic evening". -

Deciding to read more memoirs again, I picked up Alexandra Fuller’s Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight (first read about 6 or 7 years ago). I enjoyed this book. Fuller’s memoir quickly draws the reader into her girlhood growing up in Africa with candor and humor. Fuller weaves her story back and forth between an intimate portrait of her family and the violence surrounding them. Violence is not just a backdrop; this violence, and the lack of political stability in the countries she grows up in, shapes her family (and contributes to her mother’s descent into alcoholism and madness). It doesn’t sound like there should humor here, but Fuller pulls it off without sounding callous and even with a certain amount of warmth.

-

***Review written in 2015, all time favorite***

This is by far the most remarkable memoir I've read in years. The author has that rare gift, being able to speak to us through the eyes and mind of the child that she was. She was nicknamed "bobo", growing up in African during the years from 1972 through 1990.

This British family was always in hostile, desolate environments, moving from Rhodesia to Zambia and Malawi. With the author's wry and sometimes hilarious prose, we feel her encounters with mosquitoes, scorpions, snakes and more. The book also touches upon politics and racism in South and Central Africa and the relationship of blacks and white during wartime.

Through her rich descriptions of sights and sounds we know that she truly loved this land of rich, pungent flora ad fauna. If you read one memoir this year, consider this one :) -

This is a wonderfully detailed memoir of the author growing up in southern Africa amidst civil war, terrorism, and blazing heat that threatens to kill crops, livestock, and people. My most frequent thought reading this book was, “This is so very different from the way I grew up.” From earwigs skittering across the living room when the Christmas tree candles were lighted to the pair of rats living in her bedroom, and from clinging on while her dad drove around shouting for the laughing kids on the car roof to sing louder to her mother’s breakdowns after losing three children, Fuller presents each experience just as she remembers it, with little to no commentary. Her bluntness is refreshing. She relates what her upbringing was like - the good and the bad - and leaves the reader to think for themselves, not breaking the pace of the narrative with reassurances.

Even when it comes to her parents’, her white neighbours’, or black officials’ racist attitudes (to one another and to Indian merchants), she doesn’t excuse or condemn anyone; she lets their words and actions speak for themselves. The closest Fuller comes to a commentary on racism is when telling about her boarding school desegregating. She gives an account of meeting the first black student to transfer from his former boarding school, talking to him, finding out that he is polite and doesn’t have the stereotyped “African manners” and that his family is much better off financially than any of the white students’. As more black students and staff transfer in, a drought comes on and the students are made to share bathwater. Fuller recalls how as a child she marvelled that she didn’t get a rash or change colour after bathing in the same water as a black child. This is the only hint of commentary that really came through, with the implication that this was the first time Fuller started re-evaluating what she had been told to think her entire life, instead reflecting on her firsthand experiences. It broke from the neutral style of the rest of the narrative, but it was a wonderful moment.

This was a great book, pulling me into a very different world from my own, but describing everything in a brisk, vivid way that made it easy to picture. It was a unique perspective that at times took me far out of my comfort zone, and made me consider how varied individuals’ viewpoints and experiences can be, even when growing up at roughly the same time. -

I totally, TOTALLY loved this book!!!!! I know I tshould think a bit before I write something, but I am carried away by my emotions. I love the family, all of them. How can I love them, they are so very far from any way I could live my own life, but nevertheless I love them to pieces. Their lives are hard, but they get through, one step at a time. They know what is important. They don't demand too much. Oh the mother, my heart bled for her. I know she is manic, but who wouldn't be - living through what she does?! Africa is hard, but on the other side I grew to truly love it. OK, I couldn't live there but this author made me love Africa and that is strange because it has so many problems, there is so much wrong, so much that has to be fixed.

The dialog is beautiful:

Mum has been diagnosed with manic depression. She says. 'All of us are mad,' and then adds, smiling, 'but I am the only one with a certificate to prove it.'

The photos are straight from the family album. You see the kids, the one's that survive, growing up.

I dye Mum's hair a streaky porcupine blonde and shave my legs just to see if I need to. Vanessa experiments with eye shadow and looks as if she has been punched. I try and make meringues and the resulting glue is eaten clench-jawed dutifulness by my family. Mum encourages me not to waste precious eggs on any more cooking projects. I learn what I hope are the words to Bizet's Carmen and sing the entire opera to the dogs. ..... I smoke in front of the mirror and try to look like a hardened sex goddess. Vanessa declares, hopelessly that she is thinking of running away from home. I stare out at the nothingness into which she would run and say, 'I'll come with you.' Mum says, 'Me too.'

And then when the author gets married, on the way to the ceremony, sitting in the car with her father who is now driving and has just handed her a gin and tonic to combat both nerves and a persistent case of malaria, her father says, "You're not bad looking once they scrape the mud off you and put you in a dress."

This family is so real. You learn to love Africa, despite all its troubles. As the tension builds in the novel the author knows when it has reached the breaking point and throws in some humor. As in life, when times are bad, you pick up the pieces, take a deep breath and go one. What other choice do you have?

And of course you learn about Rhodesia, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi. -

What a fantastic read! Alexandra Fuller took me on an amazing journey through her younger years growing up in Africa as a poor white girl. Her parents are expats from Britain who moved in the late 60's to work as farm managers. This memoir details her life from that time right up to the late 90's, a time period when Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) was at war fighting for independence from Britain. I found it fascinating to not only read of the hellish conditions, but also how this young girl named Bobo, deals with so many challenges. She brought me right into her world, one more concerned with family, and her daily life. Only a child can see the humor in situations that would scare the crap out of me. So this was not a somber read at all. As a kid, you have no idea your parents are racist, so it can be uncomfortable to read of this families ideas of blacks, but also deeply informing.

Truly, this memoir has it all, a family on the wrong side of history, a mothers mental health issues, constant loss, death, relocating, and a vivid picture of the land. The descriptions of the land were so dynamic and realistic I will never forget them. I became a part of this book, such a rare feeling! -

Whenever I read an autobiography, I compare my childhood experiences with those of the author. What was happening in my life at that age? How would I have behaved under those circumstances?

With this book, the comparisons were difficult to make. I can't imagine growing up amid so much tumult and violence and uncertainty. Not to mention numerous inconveniences and an abundance of creepy and dangerous vermin.

I'm glad I didn't grow up in a place where terrorists were so common that they were referred to as "terrs." And scorpions were so common that they called them "scorps." And I'm quite grateful that my first day of school photo does not feature me clutching an Uzi for protection.

Alexandra "Bobo" Fuller writes about her experiences in a strangely unsentimental, matter-of-fact way. Be it fear, fun, or heartbreaking loss, all is recorded with equal detachment. Maybe it's just her writing style, but I wondered if a young life filled with danger and uncertainty and pain taught her not to feel anything too deeply.

If Fuller's family and friends are any indication, it would appear that white people can only cope with African life through heavy boozing. Full-grown adults with families drink like college boys on a bender! I guess it helps them handle the stress and loneliness and tolerate the intense heat. But it made me a little queasy thinking about the hangovers they must have suffered.

I did like the story about the exploding Christmas cake, though. Nothing like a little flambe to brighten your holiday. HA!

For me the book was both informative and entertaining. Also quite sad at times, but never melodramatically so. It opened my eyes to still more of the complexities that are the very definition of Africa. The residual colonial attitudes were also quite a revelation to me.

The writing is excellent, if a little disjointed at times. It's written mostly in present tense, the curse of my existence. If not for that, I might have gone with five stars. -

The author writes of growing up in the African countries of Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia. I love those books that make you want to see/smell/hear/feel the countries they are describing, and this is one of those. "I appreciated that we, as whites, could not own a piece of Africa, but I knew, with startling clarity, that Africa owned me."

They were poor. They struggled. Life wasn't easy. Her mum is a manic-depressive ... unfortunately, enduring the death of some of her children didn't help. "Mum has been diagnosed with manic depression. She says. 'All of us are mad,' and then adds, smiling, 'but I am the only one with a certificate to prove it.' ...lol

3 Stars = I liked the book. I'm glad I read it. -

I read

"Cocktail hour under the tree of Forgetfulness" first, and found this book too repetitive - although it was written first. I loved Cocktail hour more.

However, I enjoyed Alexandra Fuller's candor, honesty, wit and great writing style as usual.

I somehow had enough now for a while of all the hardship, tragedy, hurt, and everything else related to the wars in Africa and everywhere else. I have experienced much the same as Alexandra Fuller, being part of the revolutionary times, the same wars, as she did. I can probably write my own version of it as well, but I don't want to.

She says in "Cocktail hour under the tree of Forgetfulness":

I have read quite a few war-related memoirs lately and it is getting to me. I need some balance now.

" No one starts a war warning that those involved will lose their innocence - that children will definitely die and be forever lost as a result of the conflict; that the war will not end for generations and generations, even after cease-fire have been declared and peace of treaties have been signed."

Besides, reading all the books about war, including the Second World War, the Holocaust events, the French Revolution, Africa and Asian wars, we can conclude that nobody should complain since the person standing next to you might have had it much worse (a thought from "Small Island" written by Andrea Levy).

I will definitely find her other books to read, she's worth it! I just need a break right now. -

Find all of my reviews at:

http://52bookminimum.blogspot.com/

The only reason I read this is because Alexandra Fuller provided the cover blurb for

Where the Crawdads Sing . . . .

I’m not even sorry either because I probably would never have heard of this memoir otherwise.

Alexandra Fuller’s family arrived in Rhodesia via way of Darby, England in 1966 when she was only a toddler. This is the story of her childhood as a farming family in what originally was a country ran by whites under British rule through the revolution where Rhodesia became Zimbabwe under Robert Mugabe’s control. It is a tale of strength in both body and spirit about a family constantly fighting the odds, yet somehow never quite giving up. With moments of extreme sadness that are counterbalanced by a delightful sense of humor . . . .

“Can I help you?” We can’t trust anyone anymore. Not even white men. It is only then we see that both men are armed with thick shiny black Bibles. Mum shuffles her gun behind her back. “Oh shit, Jesus creepers.” Bible outstretched, hand extended. He introduces himself and his partner: “And we’re here to tell you about the Lord.” He’s American. I start to giggle. Mum sighs. “Well, come in for a cup of tea, anyway,” she says.

Recommended to fans of

The Glass Castle. -

The first few lines are gripping, to say the least.

Mom says, "Don't come creeping into our room at night."

They sleep with loaded guns beside them on the bedside rugs.

She says, "Don't startle us when we're sleeping."

"Why not?"

"We might shoot you."

"Oh."

Just a taste of what life was like for young Alexandra "Bobo" Fuller.

Living in a house with no electricity, Fuller recounted how she and her sister employed the "buddy system" to use the bathroom at night. One girl used the toilet while the other held a candle high to check for "snakes and scorpions and baboon spiders."

"I have my feet off the floor when I pee."

Um...baboon spiders? Eek!

In 1974, when many white residents were fleeing Africa, Fuller's parents bought a farm smack dab in the middle of twin civil wars in Rhodesia and Mozambique. They erected a huge fence, topped by barbed wire, and adopted a pack of dogs. They drove around in mine-proofed Land Rovers. Mama was packin' an Uzi.

Fuller's Mum is really the star of this show. Alcoholic and racist, she bemoaned, "Look, we fought to keep ONE country in Africa white-run..." Her attitudes seem shocking today, but were sadly shared by many at the time. She had an abiding respect for Africa, but not its people.

This is a gritty, "warts and all" memoir. Fuller's early years were anything but dull. But be warned...

if tales of irresponsible parenting and child endangerment drive you up a wall...you should probably stay FAR away from THIS book. -

I read this book (well, most of it, I admit, I didn't finish and didn't want to) while in training as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Namibia, Africa. I found the writing to be disjointed and the colonial attitudes to be far too accurate. I might have liked it better before going to Africa, before seeing first-hand what various colonizing governments did to people, but maybe not. I might have liked it better if she told her memories in order, rather than jumping around so I had some clue as to where and when she was. When I left Africa, I left the book behind for someone else to read (reading material is in short supply for PCV's) and didn't mind a lick that I hadn't finished it.

-

A well-written memoir that was fascinating if only because the author is exactly my age, born the year I was born, and lived a life so very different from my own. As she described each stage of her upbringing, I found myself thinking about what I had been doing at that same age and marveling that the two of us could possibly have occupied the same world at the same time. I envy her when I should probably not -- her life has clearly not been easy, but it has been rich with experiences. The other reason I really enjoyed this book was the sometimes startlingly candid and dispassionate voice of the narration. There's a lot of beauty in this prose...even the most terrible parts of her story are beautifully rendered. Her style shows a restraint that I fully appreciate (others may find it disquieting). She unflinchingly describes her life and does not apologize for it nor cheapen it by gaudily harping on lessons she has learned. She gives the reader credit for being able to figure it out. Sometimes quite funny. Often very sad. In the end, uplifting and powerful.

Good stuff. -

Alexandra (Bobo) and her sister, Vanessa, are some kick ass tough kids. Raised by their parents on farms in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi during the 1970’s, they are white Africans, exposed to deeply ingrained racism from birth. They have free reign among scorpions, snakes, leopards, and baboons and they live in the middle of the Rhodesian war. The girls learn to load and shoot guns to protect themselves from terrorists in this long civil war. Mixed in with these geographical hardships is their family’s struggle and acceptance of the loss of three other siblings (how could the reader not forgive Mum’s love of gin and tonic?). An honest, humorous and endearing look at an unconventional upbringing in Africa.

Well written. The author did an excellent job of plucking out the most memorable moments to produce a flowing narrative. Recommended. 4.5 stars. -

I genuinely hated this book and that's rare. The characters made me angry. Not in a "good, I get to see them grow" way, more in an "I hope they get shot and go away" way.

-

Her writing is beautiful, descriptive. You can smell and taste Africa; sometimes you can even smell and taste blood and liquor.

I would have never have dreamed of reading a book about Africa; the country just never appealed to me. But my friend, who is a teacher, and who lives part time in Africa teaching English at a school she had started, recommended it. It is a true story of a white girl growing up in Africa during the civil war, and it smacks of colonialism and racism, both of which I dislike. So I decided to give it a try, and I am glad that I did.

It begins in Rhodesia in 1976. Alexandra's parents go to bed at night with guns near their bed, the fear of terrorists is great. The girls take a flashlight to the loo in the night and have fears of snakes, scorpions, baboon spiders, and anything else that may be lurking.

Then when they rush back to their bed they take a flying leap from the floor onto the bed because of the fear that a terrorist might be hiding under the bed and just might grab their legs. In my childhood, when I got up in the middle of the night, I would run through the kitchen turning on the lights on the way to the bathroom, and when I returned to my room I would also take a flying leap onto my bed. My fears were not of terrorists but of the bogyman. I knew the bogyman wasn't real, but they knew the terrorist was.

The book was hard to enjoy at times since my mind was often on the children, and I kept questioning the parent's reason for bringing them to Africa during such a turbulent time. Then my mind would wander to America, and how parents took their kids across it in covered wagons, and how dangerous that was because sometimes entire families were killed or died from starvation or other causes. I justified Alexandra's parents in this way.

Alexandra's mother was an alcoholic, and in time she lost her mind slowly as she lost one child after another. The girls, even at a young age, lived in fear for their lives. It seemed that they were too young to even have to be thinking about death. But they all saw death in many different ways, some deaths being too horrible to have been inscribed into their minds. The slashing of bodies is not a pretty sight.

How much can a parent really protect their children? Life on this planet is never without dangers; some people are just more lucky than others to live a life where they have few fears. I look back on my life and realize that there were many times that I could have been killed by something I had done when I was young and wandering the countryside by myself. Life can be so horrible that it is no wonder that many dream of heaven, but Alexandra still dreams of Africa. -

As an avid reader, it often surprises people when they learn that I rarely re-read books. I know that a lot of people find great enjoyment from repeat readings, discovering new layers to the story and gaining a better understanding of the book. I look at it a bit differently. There are so many wonderful books out there and I'll never be able to read them all. Usually when I choose to re-read a book I feel like I'm wasting time that could be devoted to reading a new book.

My reason for sharing this is simple... I have read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight not just once, not just twice, but three times! There is no stronger endorsement I personally can give. Alexander Fuller takes risks with her writing and grammar. I found myself marveling at her bravery. It's always risky to deviate from standard writing format. Some people can be put off immediately, but I found it charming.

The ingredients necessary for a great memoir are all present. The reader is transported back in time. I felt as if I were in Africa, experiencing Alexander's life for myself. She doesn't shy away from showing her family for who they are, warts and all. The book cycles from heartbreaking episodes to moments of crystal clear beauty and life affirming incidents. It's a very sensual book, her sharp prose conjuring up the sights and smells of the African countryside so vividly that I actually missed it when the book was over. Hence the duplicate readings. I wanted to go back, even though I knew I'd have to experience the heartbreak again, because it was a place I wanted to visit one more time. -

“I am African by accident, not by birth. So while soul, heart, and the bent of my mind are African, my skin blaringly begs to differ and is resolutely white. And while I insist on my Africanness (if such a singular thing can exist on such a vast and varied continent), I am forced to acknowledge that almost half my life in Africa was realized in a bubble of Anglocentricity, as if black Africans had not culture worth noticing and as if they did not exist except as servants and (more dangerously) as terrorists.”

I picked up this book several years ago with the hope that it might help me make sense of my own relationship to Africa – the strong but confusing bonds that arise from childhood immersion and are easily discounted among adults but can never quite be brushed aside. At first, it seemed that the entire book and the author herself would have laughed mockingly at that quaint desire for commonality. Alexandra Fuller’s African childhood was much more eventful and harrowing than my own: growing up a desperately poor farmer’s daughter in the epicenter of the Rhodesian war for independence, with Uzis a more common accessory than handbags, and a dysfunctional, alcoholic, supremacist, emotionally remote family, before bouncing around ex-British colonial East Africa as tenant farm managers. I don’t enjoy immersing myself amid characters that are depressed, lost, or unmoored, so there were a couple of points where I might have abandoned the book had it not been for the funny, personable dialogue of the children trying to make sense of their conditions and the emotions of the adults.

But then I realized that the book is a love letter. By opting not to romanticize her family life, Fuller allowed her Mum, Dad, and older sister to shine as “hard-living, glamorous, intemperate, intelligent, racist, … taciturn, capable, [and] self-reliant.” Their frequent moves and their physical and racial isolation force the family to learn to accommodate each other’s flaws/quirks, and they become very tight-knit because of (not in spite of) their individual eccentricities. They love each other not because they as individuals are sympathetic, but because together they survived both Africa and a tumultuous family life. Had Fuller chosen to whitewash or idealize her family life, she would have deprived them of this shared experience and been left with a cardboard cutout of the real thing.

It’s also a love letter to the land, using words far more poignant and evocative than those that

Margaret Mitchell puts in Scarlett O’Hara’s mouth. Given the surface-level dissonance of a white family claiming an African identity, Fuller works hard to demonstrate how their roots, their loyalty, even their identities are all inexorably bound to the earth. Her descriptions of sounds, smells, and miscellaneous details were truer than true and made me ache with memory. The rainy season that brought with it gray solid sheets of water which rendered roads as thick and sticky as porridge. Weekend holidays on the shores of Lake Malawi running wild with expats-like-us while burning to a crisp. The mosquito coils, the baobab trees, the explosion of day birds, the greasy fish stews over rice, the smells of black tea, cut tobacco, fresh fire, old sweat, young grass. Hauntingly evocative.

In her epilogue (well, the “Reader’s Guide” published at the end of the Random House edition), Fuller recounts how she repeatedly tried to write a fictionalized version of her childhood, failing in part because her adult values demanded that she “write into full life the voices of the black men, women, and children who had been silenced by years of oppression,” even though her childhood had included no such voices. In the end, she opted to write her life exactly as it had been, racist elements and all, and included a suggested reading list at the end for the “powerful, beautiful, often sly and funny literature of black Africa.” Though criticized by some other reviewers, this choice to consciously stare everyday white supremacy straight in the face, instead of caricaturizing it or demonizing it, strikes me both as brave and as an important contribution to post-colonial storytelling. -

A classic memoir that conjures up all the sights, sounds, smells and feelings of an Africa on the cusp of a colonial to postcolonial transition. Fuller’s family were struggling tobacco and cattle farmers in Rhodesia (what later became Zimbabwe), Malawi and Zambia. She had absorbed the notion that white people were there to benevolently shepherd the natives, but came to question it when she met Africans for herself. While giving a sense of the continent’s political shifts, she mostly focuses on her own family: the four-person circus that was Bobo (that’s her), Van (her older sister Vanessa), Dad, and Mum (an occasionally hospitalized manic-depressive alcoholic ) – not to mention an ever-changing menagerie of horses, dogs and other pets. This really takes you away to another place and time, as the best memoirs do, and the plentiful black-and-white photos are a great addition. (My free copy came from the Book Thing of Baltimore.)

A few favorite lines:

“My soul has no home. I am neither African nor English nor am I of the sea.”

“We eat impala at each meal. Fried, baked, broiled, mined. Impala and rice. Impala and potatoes. Impala and sadza.”

On her brief conversion: “Once (when drunk) at a neighbor’s house I take the conversation-chilling opportunity to profess to the collected company that I love Jesus. Mum decalres that I will get over it. Dad offers me another beer and tells me to cheer up. Vanessa hisses, ‘Shut up.’ And I tell them all that I will pray for them. Which gets a laugh.”

“Since October, Mum has been using a hypodermic needle to inject the Christmas cake (bought months ago in the U.K.) with brandy.” -

I read an article by a book reviewer a little while ago in which they talked about how sick they were of "growing up in fill-in-the-blank" books and wished people would be more original. I think that's incredibly misguided. Growing up isn't a cliche, it's just something that happens a lot that's important. So people are going to write about it, and good for them.

They don't usually write about it this well though. This is one of those books that tops out on many different levels at the same time- the language is beautiful, the dialogue is great, the people come alive for you, it's hilarious, it's sad, it's beautiful, and it deals with the subject of entrenched racism incredibly well, by simply telling the truth about how people were and what people did, without ever stretching to make a political point. It's fantastic, and I'd recommend it to anybody. -

An unconventional memoir, and I think Fuller's commitment to write about her life in Sub-Saharan Africa through her own perspective as a child is an interesting stylistic choice, but for some reason, I dreaded this book as I was reading it, and I couldn't wait for it to be done. I think I struggled with so many short chapters skipping around in time without a reason or frame, and as a result, I felt anchor-less. I think her voice may speak to others more than me, but I simply did not enjoy reading this book.

-

Just an astonishing memoir, beautifully written, packed with wry humor. Read it, enjoy it, marvel at the tightrope

No cheetahs are harmed, but the impalas typically arrive as steaks.

Fuller walks as she describes the fall of apartheid from the minority white perspective (without nearly enough contrition, but that's apparently a matter for a different book).

Alexandra Fuller was a handful as a kid, and she wrote it all down while she still remembered it.

Born in 1969, she's technically a gen-xer but the childhood she describes will be oddly recognizable to some American baby boomers. ("Coke adds life" she notes ironically at one point, swilling one as she's flopped beneath a formal table soaking up rarely-encountered air-conditioning at an off-hours country club.)

The story centers on Fuller's parents, unreconstructed white settlers who were stunned to see Rhodesia fall.

Her parents come across as hard-drinking, passionate, and harum scarum. They're cursed with bad luck and armed with fatalistic, philosophical British good humor. And Uzis.

What makes the book remarkable is Fuller's nuanced account of her colonial-era childhood. You wouldn't think a five-year-old's mysterious rash would become an instantly awkward incident of politics and race relations. But when a rambunctiously itchy young Fuller shrilly demands that the two family servants examine her "on my downthere, man" to assess and relieve the itch, the servants take refuge by (entirely reasonably) feigning deafness.

Fuller's parents are absent, she is fully accustomed to ordering both adults around and being obeyed, and she is furious and mystified at being ignored. The adult Fuller includes enough details (her habitual childhood imperiousness to darker-skinned adults, those adults' dismay, then anger at her impossible harping) for us to understand exactly what is at stake, and also to let us understand the ironies. Fuller's nanny had told her not to play in the bamboo patch, but had she listened?

Other details are just as revelatory. Late in the book, when Fuller's family discovers their home has been ransacked, their greatest loss is the mother's rings. Not because of sentiment, but because the rings are the family's single valuable possession, and must be pawned as security prior to planting the tobacco crop each year.

The book is full of such insights told so truthfully that on the book's publication, Fuller's family quit speaking to her for months. The vivid details are entirely worth it. -

I was completely mesmerized reading this highly compelling memoir of Alexandra Fuller's childhood experiences as a British expat family living in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), during the time of ending colonialism in the 70s-90s.

This book captivated me on so many different levels:

I was captivated by the writing: the author writes with candor and wit about her chaotic, often tragic childhood. The writing is poetic, yet understated, letting the beauty and harshness of the landscape and her experiences speak for themselves.

I was captivated by the “larger than life” personalities of her parents: Alexandra’s childhood revealed a wild, dysfunctional family with eccentric parents who lived life to the fullest, but also drank a lot, acted recklessly, lived on the edge, and practiced an extreme degree of hands-off parenting.

I was captivated by the stories: The stories were fascinating, dangerous, unimaginable, maddening, crazy, and hilarious. They catapulted me from sorrow to hilarity and back again in the span of a page.

I was captivated by the stark realities of a harsh life: Alexandra grew up in a world where children over five "learn[ed] how to load an FN rifle magazine, strip and clean all the guns in the house, and ultimately, shoot-to-kill." Her entire experiences were against a backdrop of ongoing struggles between blacks and whites that continued for many years. Alexandra candidly relates these experiences and the racism of her parents which pervaded her youth.

This is a book I definitely plan to read again, knowing that I will get even more out of it the second time.

Audiobook Notes: The audio version is narrated by Lisette Lecat and it is a brilliant performance. Her voice, tone, and pacing supported the writing perfectly, I kept imagining it was the author herself speaking to me, and I was readily immersed in the dreaminess of the landscape, and the realness of the stories. She did a masterful job creating distinct realistic voices with multiple accents to distinguish between the different ages, genders, and nationalities found within the stories. Winner of AudioFile Earphones Award -

4.75

What makes Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight an outstanding memoir was Fuller's interesting choice to tell the story of growing up as an "expat-like-us" in Africa from a child's POV and the fact she did not tie herself to recounting her childhood in a linear manner. The latter was effective since Fuller doesn't get bogged down in the day-to-day mendacity that is life and she can focus on events and stories that give a full picture to growing up (white) in Africa. Her choice to use a child's POV is incredibly clever since it allows her to touch on issues like racism, post-colonialism, and dysfunctional family dynamics without needing to present apologies, excuses, or really any editorializing and that let's her experience shine through.

What makes Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight an outstanding book is Fuller's feel for language. Her feel for dialogue (naturally reconstructed, but incredibly realistic) is outstanding and her rendering of a child's understanding of language is superb. She is also a hell of a writer.

My only complaint was the ending -- it was far too abrupt. We suddenly jump ahead to her wedding, which wouldn't be horrible, except that suddenly 10 years (or something) have passed since the last event she recounts and since none of the memoir is written from an adult perspective, this relatively short portion is jarring. -

This is the second book I've read by fuller and I just love her writing style and the story she has to tell. Growing up in the 70's as ex-pats in a country still fighting for it's own independence. Where it's normal to live carrying guns and needing escorts just to go to the local village, in case you drive over landmines or get assaulted. And then to have to grow up in a family as unusual as alexandra's is just such a fascinating story. A mother who is heartbroken from a loss of a child, who drinks to forget, who fights tooth and nail for her family. A dad trying to keep it all together through farming but who is restrained by political changes going on at the time. And two young girls growing up in a changing Africa. It's a brilliant story.

-

I quit a book club to avoid titles not unlike this stylistic disaster. Displaying a tin ear for rhythm, Fuller lazily stacks adjectives past the point of diminishing returns. Overripe and olfactory, vast swaths of text read like an Avon catalog, if the hot scents were wood smoke, fried fish, lion piss, and cattle shit. Faux-literary and mock-tough, it made me embarrassed to be seen with it in public.