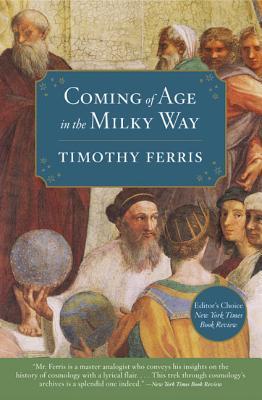

| Title | : | Coming of Age in the Milky Way |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0060535954 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780060535957 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 512 |

| Publication | : | First published May 4, 1988 |

| Awards | : | Pulitzer Prize General Nonfiction (1989), American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award (1988) |

Coming of Age in the Milky Way Reviews

-

Light on science, heavy on the history of cosmology.

It's a nice, short read.

There is, however, one horrible mistake.

Ferris credits Christian creation mythology with contributing the idea of a beginning to time.

There is no historical (or logical) basis for this.

The theory that the universe began a finite time in the past was a natural outcome of the distance-correlated redshift of extra-galactic objects.

It is irrelevant to the history of scientific progress what beliefs some desert religion happen to hold before the invention of the telescope.

Religion can NEVER contribute scientific progress.

It can only HINDER science by defaming (Charles Darwin), torturing (Galileo Galilei), and outright killing (Giordano Bruno) scientific thinkers. -

I had always meant to read this book, but somehow I never had gotten around to it. But I decided recently that, while I spend all day thinking about astronomy (as an astronomy grad student), it might be good to get a "popular science" take on some of these topics so that I can actually speak intelligibly about astronomy with non-astronomy folks.

Despite the fact that some of the later chapters are out-of-date on the astronomy and physics results, this was a very fun read. The first section on historical astronomy was particularly fun; it was very similar to the astronomy class I took in high school that got me into the field in the first place. Ferris does a very nice job of conveying the material more or less accurately, while also making it approachable for the lay audience. The one quibble I would have is that people like Caroline Herschel, Maria Mitchell, Cecilia Payne-Gaposhkin, Henrietta Leavitt, Annie Jump Cannon (got the pattern yet?) didn't get as much attention relative to others as they deserve given their contributions to the field. This was particularly noticeable to me because I had just read a biography of Maria Mitchell and was in the middle of a biography of Cecilia Payne-Gaposhkin. It is one of those amazing things - some of the most important discoveries in 19th and 20th century astronomy in this country were made by women, most of whom couldn't get PhDs, barely got recognition for their work, and were often discouraged from thinking about the science. Maria Mitchell found a comet, and in so doing single-handedly brought much-needed credibility and prestige to the struggling field of American astronomy and the fledgling Harvard University. Henrietta Leavitt basically solved the biggest problem in astronomy - how to measure distances to distant objects - without which Edwin Hubble could not have made his discovery of the expanding universe. Cecilia Payne-Gaposhkin was the first to figure out the puzzle of what stars are truly made of and created what many consider to be the best astronomical thesis ever written. -

The perfect layman's guide to the universe. It gets pretty hairy as soon as quantum mechanics take the stage about 3/4 in, especially if you have no background in physics whatsoever (as i certainly don't) but i doubt Ferris could have written about the various quantum theories in a simpler way, at least not without cheating the subject of its inherently complex grace. I came away from this reading experience with not only a renewed interest in astronomy (and science in general, really) but also a greater appreciation for the size of the universe and our relative inconsequence in the grand scheme of things. Exciting stuff.

-

Ferris provides his reader with an extremely abbreviated version of discovery from Columbus through now. There are some aspects of his stories that are lesser known, which makes them quite enjoyable. The layout of the book is really great as well. Not too many books provide a summary of biology and physics in tandem. Adding to that, Ferris keeps each subject brief so that it packs as much information as possible, while remaining fairly uncomplicated. Considering all the positive aspects of this book, I can see why it received the accolades it did. However, historians must have a hard time reading this book. It's not that Ferris kept the descriptions of Newton and Darwin brief. It is more that his representations of the scientists seem to be under researched.

If Ferris is going to portray various scientists in a manner that is far different from how just about every other author, whose life work has been to study the biographies of their chosen scientist, has portrayed these scientists, then he is going to need to provide some proof for his alternate version of their personalities. For example, according to Ferris, Newton was humble, didn't care about fame, and instead cared only about the work. This would describe Darwin but not Newton. When describing Newton's reputation as a "monster", Ferris seems to misunderstand why people called him that. His depiction of Darwin was equally naive.

Writing books that are short, easy to understand, and not overly complicated are essential in helping scientific information disseminate into the public at large. Anytime writers choose brevity over jargon-laden prose, a book always trades a bit of accuracy for relatability. That is par for the course. So, my critique is not coming from an ideology that believes books should be both brief and extremely accurate. However, they should strive to be as accurate as possible, not just in relating the science itself, but in portraying the scientists' personalities. If an author does not know enough about the life and personality of the scientists, then the author should just leave them out. It's preferable to an inaccurate portrayal. -

I struggle with the rating on this one. The author is inaccurate and dismissive on questions touching on religion and inaccurate and incomplete on matters of women's contributions to science. The book is frustrating in the earlier historical parts because of this. It gets better in the third part, where he waxes rhapsodic about physics, but he's also not nearly as eloquent as he thinks he is. That said, the parts about the "stairway to heaven" describing conditions going back to fractions of a second after the Big Bang and the scale of the universe were pretty good. A decent read but there are much better science books out there that cover similar material.

-

Having had no physics or chemistry beyond the eighth grade, some of this was way beyond me, but it's a testament to Ferris' beautiful prose that I was still able to get the basic gist, finish the book, and get a lot out of it. It's not an easy read, but it just kept blowing my mind and making me think. There are so many great thoughts encapsulated here! If you like to be challenged by science, this is the book for you.

On a side note, as a musician, who ostensibly makes beauty for a living, who feels called to put it out into the world for the sake of humanity, it was really fascinating to learn that physicists feel very similarly about their work. -

A popular history of astronomy, and particularly cosmology, with some physics and a little geology and biology, this is apparently considered a classic of popular science writing, although I'm not quite sure why. It's a low-level popularization (not intended as derogatory; I mean it's a simple account with no mathematics, intended for readers with no previous knowledge) and while there were as always a few anecdotes I didn't know, I'm now a bit beyond that level.

It wasn't a bad book by any means, but just not in the league of Weinberg's The First Three Minutes or the books by Marcia Bartusiak, Kip Thorne, Brian Greene, Lee Smolin and others I have read in the last three or four years on similar themes. It's also of course after 35 years a bit dated when it gets to the "present" (dark matter is barely mentioned, as it is still a new idea; dark energy and the accelerated expansion weren't known yet; string theory was just getting started, there were no exoplanets known, and so forth-- it's amazing how much more is known after three and half decades), although as history its fine, just not very detailed. There is a very long bibliography, which makes it disappointing that not much has made it into the text. -

I have given this book five stars because I really enjoyed it, I learned a lot, and it awakened in me a desire to learn more science. I also learned that physics which I thought was something I couldn't understand is actually understandable. All that aside, this book is not for everyone. It is part history and part science. It is a great survey of science, scientists, all that we have learned in the last few thousand years. It is divided into three parts: Space, Time, and Creation. It is in the last section where is introduced to quarks, particles, quantum physics, and string theory that it can really get complex. I understood more than I anticipated and am eager to learn more. Exploring science has made me appreciate the design of nature and my Creator. As humans explored and answered questions, we also found more questions and so our search continues. If like me you love history and are also interested in science give this book a go. You will not be disappointed.

-

Fantastic book that covers the relatively short history of cosmology and human discovery that acted to expand the long history of the universe.

This book has been on my shelf for a while but, like Carl Sagan's Cosmos, once I picked it up I couldn't put it down. It's easy to read, while still appealing to readers with some background knowledge. -

This was like a coming-of-age story, except with the journey of the human mind. Light on the science, heavy on the history and pretty decently written. If you have even the slightest interest in space, you'll enjoy this one.

-

I hate to use cliches but in this case, apt - Ferris has a lyrical quality to his writing about the evolution of knowledge about the universe - from the earliest days of the Greeks to the latest cosmology.

The book in the first few chapters deals with the discovery of planets, moons, and the heliocentric perspective of the solar system. It is mostly told via 'great man' chapters from the usual suspects - Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, Herschel and others.

Of course as science got more complex with better tools, further truths about the universe became a mix of discoveries upon discoveries from a mix of astronomers and physicists. And these chapters are less about individuals as geniuses (some exceptions here: Einstein) than about what was learned and how.

A reasonably easy read, with no math although having at least high school physics helps. Excellent illustrations throughout. It only bogged down in the chapter on subatomic particles but fortunately, the next chapter got more macro and was easier to follow.

Worth reading? Yes to anyone who wants in one place a grand scale, chronological epic narrative of how humans have come to understand the universe in which we live. -

I loved this book! Though not a dry collection of facts, it's crammed with information. It's a feast for the mind. It's more like a biography or a historical novel than a textbook. It expresses the beauty and power that happens when we get science right. It was perfect for me because I know little about the subject but wanted to absorb an overview written in an easy to read and entertaining manner. Though so much of modern physics was established well before I was born, none of it was taught in my high school general education classes. We didn't get past Newtonian mechanics.

Human attempts at the explanation of our world are a mess of false starts and tangents. The early scientists were philosophers. They saw the randomness and unpredictability of this terrestrial muck and imagined that perfection must exist in the heavens. Many of them didn't observe the stars; they contemplated them, imagining symmetrical geometric beauty and music. Those who actually observed the stars and the planets worked hard to fit what they saw into the prevailing theories. They were also led astray by their own perceptions, such as that the earth stands still while the heavens move. Without the empiricism of science, we'd have the same beliefs today.

It's so easy to be complacent in hindsight and wonder why scientific discovery seemed to progress so slowly. This beautifully written story makes me sympathetic to the struggles. The people are brought alive with wonderful descriptions. I really enjoyed the trenchant profiles of Tycho, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton. Until now, those individuals for me were a sculpture at Griffith Park observatory. Even the animation of them in the new Cosmos series didn't do it. But I'm a reader, and this book was like candy.

Reading the final chapters on the search for unified field theories made me think we have come full circle. We are still vainly searching for perfection in an imperfect universe, except now we've replaced Plato's perfect geometrical figures with supersymmetry and strings and hyperdimensionality. It's harder to follow as the concepts get more abstract. The author continues with colorful descriptions of eccentric and egocentric scientists and their sometimes clashing, sometimes meshing theories.

Sometimes as I read about theoretical physics I felt like the character Charlie in Flowers for Algernon might have felt. I could appreciate only a mere shadow of the many concepts contemplated by great minds. Without really grasping any of it, I managed only to pick up a few terms I can drop to sound knowledgeable in conversation. But it was fun to read.

The writing is gorgeous. The author is so skillful in his use of vocabulary, and of literary devices such as hyperbole, metaphor, and simile, that the reading experience never felt trite or pretentious. It just flowed. Sometimes it was as pleasurable as eating chocolate -- and for me that's saying a lot.

"Space may have a horizon and time a stop, but the adventure of learning is endless." This book gave me a taste of the joy of that adventure and at the same time a bittersweet sense of humanity's -- and my -- ignorance. I can't recommend it strongly enough.

Addendum: I do have a couple of complaints that I chose not to mention because of my overall enchantment, but I keep thinking about them. The author mentions a mythical deity an awful lot for a science book. Though he describes many ways the church hindered scientific inquiry, in one passage he actually credits it with inspiring further exploration into the age of the earth. I don't understand how someone who so clearly comprehends the magnitude of what we have learned from science could possibly reconcile that with religious belief. I was unable to hold two such incompatible world views without feeling schizophrenic. One of them had to go, and my reading list and profile should make it clear which one that was.

I thought the chapter on Darwin was rather out of place. Maybe the author was trying to draw an analogy between the modern synthesis as a sort of "theory of everything" in life science with the search for something similar in astrophysics and cosmology. I found it annoying that he chose to quote from the 1860 edition of The Origin of Species, which contains the phrase "by the Creator," which Darwin added possibly because of pressure from religious groups. See

http://darwin-online.org.uk/Variorum/... and

https://edge.org/conversation/there-i...

One more thing. Gendou gave this book a poor review because it's "light on science." I agree, but that doesn't make it a bad book. Right now I'm trying to read Not Even Wrong by Peter Woit. I don't have a background in mathematics and physics, so though it covers much the same subject matter as Coming of Age in the Milky Way, I'm finding it incomprehensible. I might try reading Lee Smolin's The Trouble With Physics, because it's recommended for a more general readership, but what I'm starting to see is that you don't really need to comprehend physics to realize that string theory is a bit like complimentary and alternative "medicine" in that a lot of money and effort are being spent on hairbrained, dead-end concepts -- ones that are "not even wrong." -

A must read for anyone interested in the history of the science of the cosmos.

-

A random goodwill buy that turned out to be super insightful introduction to astronomy and physics.

-

I hate the penultimate chapter and as wary of the last, but I still give this book five stars. It is fascinating from the first sentence until the last sentence of chapter 18, and so beautifully written that I am jealous of Ferris's gift for telling this story. The book may not be as amazing as the cosmos, but it is amazing for a popular science book.

-

Ferris begins with the ponderings of ancient societies and brings us forward, with clarity and painstaking research. This approach can lend itself to a predictable scientific greatest hits parade (say it with me, preferably in the singsong of Sherri and Terri twirling the jump rope on The Simpsons: and Brahe begat Kepler and Kepler begat Newton...). But Ferris does one better and balances the march of scientific discoveries with a regard for the fumbling humanity of the steps, both forward and back, toward piecing together an understanding of the universe in which we find ourselves.

As we as a species grew in our understanding, the universe in turn grew around us, showing us more as we were increasingly capable of seeing more. To peer out across the galaxy, beyond the galaxy, into the universe, is of course to peek backward in time. To look ever deeper into the traces of history is to dig at the mystery of the beginnings of time. And so the book is divided into three sections, following the pursuits of space, time, and creation.

Where the weave of clarity becomes looser in the later chapters of Coming of Age, Ferris steers toward the marvelous, bringing us alongside the puzzles faced by cosmologists and particle physicists in the late 20th century. It was not until these final chapters that I realized the book was written in the late 1980s, with a quick 2003 afterword appended. No matter. As it dwells less on explaining the then-current state of affairs in favor of pursuing the theoretical implications that arise, Ferris's book does not feel particularly dated (although a particle physicist will undoubtedly beg to differ).

In fact, its ending seems less dated than prophetic. Researched and written in the late 1980s, Ferris ultimately imagines and describes what from my armchair in 2013 appears to be an interstellar internet, a series of self-replicating communications hubs that would network civilizations throughout the galaxy, allowing them to interact exponentially faster than the speed of light would demand. And not only that: "Growing in sophistication and complexity with the passage of aeons, forever articulating itself among the stars, the network would come to resemble nothing so much as the central nervous system of the Milky Way. [...] Life might be the galaxy's way of evolving a brain" (379).

For all the pop science and science fiction I have been ingesting of late, this suggestion is the most eye-popping and intriguing of all, for it simultaneously hands us a purpose and relegates us to the backwaters of Purpose. The notion, seemingly Ferris's own, giveth and it taketh. It reminds me of the Portuguese man o' war, which walks and talks, so to speak, like a single animal but is in fact comprised of a colony of organisms. Perhaps my solar system is but a polyp that has yet to link up with its brethren in the formation of an interstellar intelligence (Galactus, I presume?).

Ferris then takes his bow and ends on a note familiar to fans of Carl Sagan:

"Science is young. Whether it will survive long enough to become old depends upon our sanity and courage and vigor, and, as one always must add in this nuclear age, upon whether we blow ourselves up first. 'Nothing that is vast enters into the life of mortals without a curse,' as Sophocles said, and the knowledge of how the stars shine is very great, and its dark side is very dark indeed.

"Epictetus the former slave remarked thatevery matter has two handles, one of which will bear taking hold of, the other not. If thy brother sin against thee, lay not hold of the matter by this, that he sins against thee; for by this handle the matter will not bear taking hold of. But rather lay hold of it by this, that he is thy brother, thy born mate; and thou wilt take hold of it by what will bear handling.

Therefore, we say--speaking as living and (we think) thinking beings, as carriers of the fire--therefore, choose life" (387-88). -

Really a well-written history of physics and cosmology. It was written in 1988, so doesn’t have recent developments. The sections on quantum mechanics was not as clear as the rest of the book (insert joke here.)

-

There's something poetic about the nature of the universe, and it is this as much as a desire for knowledge which drove early man to strive toward a solution of its riddles. The universe, in turn, has also driven men to write poetry, and there's something of the poetic in Ferris' history of cosmology, a book which takes us from the first recorded beliefs of our forebears through to recent discoveries at CERN. The book is structured in sections which cover first the development of our understanding of the scale of the universe, then the nature of time and its relation to space, and finally plunges into the subatomic ballet which is currently expanding our knowledge of how the universe was formed.

Ferris has a light, elegant style which lends itself well to this kind of book, both in the lyricism with which it draws the readers through the early stages and in the skilled use of metaphor which allows him to illustrate concepts in quantum physics, although these come so thick and fast toward the end that you'll not so much struggle to understand as remember them all. You can appreciate the view of one scientist who, on seeing the mass of particles predicted by quantum physics, said that if he could remember all that he would have become a botanist. Like trails in a cloud chamber, however, what is left imprinted on the reader is an appreciation of just how far we've come.

My one niggle was in the section on Herschel, where I thought he gave his sister Caroline - a skilled astronomer in her own right - somewhat short shrift. Perhaps this is understandable in a work of this scope - it certainly shouldn't detract from the enjoyment and edification which flows from its pages. -

La mejor obra de divulgación científica que había leído hasta la fecha, en 1995 (desde entonces otras también han entrado en el Olimpo, como el libro de

Bill Bryson, los de Brian Greene...). Explica las cosas desde el enfoque histórico, lo cual lo hace emocionante al tiempo que menos directo. Cuando vamos avanzando en el tiempo vemos cómo los pensadores y las ideas cambian la concepción del universo, agrandándolo y enriqueciéndolo con multitud de nuevos conocimientos y detalles. Asistimos a la mejora y refinación de los conocimientos acerca del Universo por parte de la Humanidad igual que podríamos maravillarnos de un niño pequeño que va aprendiendo cosas y obrando en consecuencia. Es un libro completamente adictivo y que está lleno de anécdotas científicas. He aprendido mucho, muchísimo, y desde luego me dejo abundante material para futuras relecturas.

Al texto en sí se le añade una extensísima bibliografía de más de 1300 libros (¡!) comentados brevemente, un útil glosario y los índices alfabético y onomástico, que añaden casi 100 páginas al libro, y lo encumbran a obra de referencia además de obra de divulgación. Una obra maestra sin dudarlo. -

I went back and forth on whether to rate this 4 or 5 stars. COMING OF AGE IN THE MILKY WAY is a wonderful but challenging book; the latter quality is particularly evident when Timothy Ferris discusses Quantum Mechanics or String Theory. In the end, though, a 5 star book is one I know I will return to, and I can't imagine not returning to this book.

In less than 400 pages, Ferris manages to describe the history of humanity's understanding of the universe, from the pre-Socratic Greeks to String Theory. There are, of course, subjects you wish he would dwell on longer, and the understanding of such subjects requires a sustained effort, but Ferris' ability to condense complex ideas and movements into a digestible length is highly impressive.

In the end, though, this book gets the 5 star rating because of Ferris' prose. Short of Carl Sagan, I've never read a science writer able to adeptly explain complicated subjects AND evoke a such a formidable sense of wonder. The language throughout is precise, elegant, and lyrical. This book not only allows for an appreciation humanity's ceaseless progress in the sciences, but it captures some of the beauty and strangeness and awe of the cosmos. -

Ferris' book is a readable and engaging summary of the history and philosophy of cosmology with supporting vignettes into mathematics, physics, astronomy, chemistry, and evolution (Darwin). He does a good job of weaving together historical events, personalities, and the little questions. Though he doesn't address it directly until the concluding chapter, throughout this book Ferris presents the human drive to know and understand our place in nature as specific questions have been posed. Thus, Ferris builds from the immediate questions and applications to the larger question of human existence and in fact, beyond with his consideration of ET. The only error I found was his referral to cell walls in human skin cells -- no animal cells have cell walls -- which does not detract from his point but is erroneous and therefore, annoying. In the world of biology, it matters that animal cells do not have cell walls. I found this book to provide an excellent historical framework in which to organize the many articles and books I have read in this area. Highly recommended.

-

What much popular science book skip through, the history of the times and the people who developed science, this book dwells on.

From Ancient Greece, Ptolemy, Aristotle, through the Renaissance, Kepler and Galileo and more, until Newton and our times, governed by Einstein. This book tells their stories, their breakthrough, and how the universe was understood in each time.

So I thought this book is more of a history of science until I got to the second and third part when it took a turn to Darwinism and (expectedly) quantum physics. By that point, it became very similar to most popular science books, which by no means is wrong.

It even gets a little technical, but just on the right amount not to bore you. Not being a physician or a mathematician, some of those concepts I still find hard to understand, but this book is another step in the path of learning. -

One of the best books that I have ever read in my life. Infact life is not worth living if one does not read this beautiful book.

Its a romantic account of the history of science and especially of cosmology. A truly beautiful book that explains the efforts, sacrifices and the science behind various theories. The rewards of understanding the book is primarily to appreciate the scientific process of enquiry, which is to question everything and be radical in the thought processes.

The sacrifices of the scientists are truly amazing!

Also urge people to also see the TV Series Cosmos while reading the book.

A reader literally gets a beautiful 365 degree view of the subject.

Couldn't resist sharing the beautiful line from the book:

"Errors can often be fertile, but perfection is always sterile".

Beautiful book. -

The most recent assessment of our universe reveals its energy output is only half what it was two billion years ago. Everything is fizzling. In trillions of years, what was once vibrantly pulsating Milky Way will become a cold, dark place. How did we get to this point?

This is the question Timothy Ferris tackled in his 1988 Coming of Age in the Milky Way. It’s an enlightening read. I’m not scientifically inclined. Yet the starry heavens fascinate me. In this I’m no different from the ancient Egyptians. Ferris traces the story of European culture’s efforts to understand how the universe works while introducing the reader to the men and women responsible for scientific breakthroughs. Well worth reading -

A fairly concise history of the sciences associated with our place in the universe - astronomy, geology, cosmology, physics - conveyed with equal coverage of the progression of the concepts and the essential biographic details of the key players. Precise in its scientific language and yet accessible and even beautifully poetic at times. I don't think a whole lot more has been discovered since its publication in 1988 that would merit major changes in a new edition. A thoroughly enjoyable read, I breezed right through it.

![The Whole Shebang: A State-of-the-Universe[s] Report](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/books/1347278841i/310330.jpg)