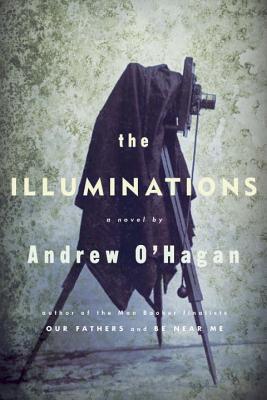

| Title | : | The Illuminations |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0771068336 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780771068331 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 304 |

| Publication | : | First published January 27, 2015 |

| Awards | : | Booker Prize Longlist (2015), Dublin Literary Award (2017) |

Standing one evening at the window of her house by the sea, Anne Quirk sees a rabbit disappearing in the snow. Nobody remembers her now, but this elderly woman was in her youth an artistic pioneer, a creator of groundbreaking documentary photographs. Her beloved grandson, Luke, now a captain in the British army is on a tour of duty in Afghanistan. When his mission goes horribly wrong, he ultimately comes face to face with questions of loyalty and moral responsibility that will continue to haunt him. Once Luke returns home to Scotland, Anne's secret story begins to emerge, along with his, and they set out for an old guest house in Blackpool where she once kept a room. There they witness the annual illuminations--the dazzling artificial lights that brighten the seaside resort town as the season turns to winter.

The Illuminations is a beautiful and highly charged novel that reveals, among other things, that no matter how we look at it, there is no such thing as an ordinary life.

The Illuminations Reviews

-

Andrew O’Hagan, I only just discovered, has been nominated for a number of prestigious awards, including the Booker Prize (1999), the Man Booker Prize (2006) and was voted one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists for 2003. He is editor-at-large for the London Review of Books. In September of 2014, O’Hagan

interviewed Karl Ove Knausgaard for the London Review of Books at St. George’s Church in Bloomsbury. At that time, Books 1-3 of Knausgaard’s six-volume novel/memoir,

Min kamp 1 (My Struggle), had been translated into English.

O’Hagan elicited something more from Knausgaard than earlier interviewers had: his silence as an interlocutor was voracious. He raised questions citing Nietzsche, Camus, Saul Bellow, Emile Zola, Ibsen. He elevated the level of discourse, provoking revelatory statements from Knausgaard about living an "authentic life," and the "lies" that we must tell in order to live with others. One question "Do individuals own their own life story?" O’Hagan posed to Knausgaard and is also a central question of The Illuminations, O’Hagan’s fifth novel.

Luke Campbell, the grandson of Anne, finds himself rooting about in his grandmother’s history in an attempt to clarify his own life. Recently discharged from the 1st Royal Western Fusiliers serving in Afghanistan, Luke is suffering a crisis of conscience from events that took place before his departure from the war zone. Looking after the affairs of his aging grandmother began a journey of discovery for Luke, revealing long-held secrets and answering the question, "whose story is it?"

The title, The Illuminations, refers most directly to the city of Blackpool and the festival of lights it sponsors each year in September, streamers of bulbs illuminating the seaside promenade until the wee hours. But the title also refers to a young man viewing a firefight in Afghanistan, Anne emerging intermittently from dark clouds of dementia, and Luke’s mother Alice experiencing flashes of insight: "It’s the hallucinations, as I call them…My mother always behaved as if the truth was the biggest thing. The photographs [Anne] took when she was young were all about that." Alice’s mother Anne, a once-famous documentary photographer, had stopped taking photographs long ago and no one knew why.

Luke Campbell had joined the Fusiliers to "look for his father" who had died patrolling Belfast during The Troubles in Northern Ireland. Sean Campbell had been in the Western Fusiliers, the same regiment that Luke joined. Luke knew his father had died but he did not know the story of his grandfather who, it was said, had flown reconnaissance planes in WWII. Without consciously setting out to uncover the whole story, Luke offers himself as a means by which Anne could return to Blackpool and her past.

Luke is close with Anne, and though his grandmother "always made too much of the men" in her life, she "spoke [to him] as a person not only ready to invest in you but ready to bear the costs to the end." His mother Alice, on the other hand, was always taken up with practicalities and resentments for being "sacrificed" growing up. "I didn’t ever think it would be so hard. So hard to face it," Alice tells her doctor. "I didn’t get to ask about my father or get a grip on the past...I would love to spend half an hour with the woman who made those pictures." Alice faces the truth with no filters, and feels the cut.

O’Hagan is

a spokesperson for The Scottish Trust and he takes seriously the responsibility for following in the footsteps of great literary figures: "some of what we understand to be literary values come from Scotland in the first place." O’Hagan points to Rudyard Kipling at least twice in this novel and the poem "If" almost charts Luke’s personal journey to manhood. Kim, Kipling’s book about the great power struggles in an India that included parts Afghanistan, sits comfortably in parallel with a young soldier’s disillusionment: the military affair in which Luke was involved in Afghanistan illustrated for him the ways that men and countries can be crushed under the weight of their experiences.

This novel is not the smooth, polished piece one associates with "great novels," but it is packed with the insights of a work three times its length. One might even say that the work is at the service of big ideas. O’Hagan, like his central character Luke, is "a bit of a thinker," and strives to touch on important themes that we face today in the world. I admit to wanting to look at whatever O’Hagan has written "and test it all against reality." -

"You don't see the connections in your life until it's too late to disentangle them," one character says in The Illuminations.

It's easy, also, to not see all the connections Andrew O'Hagan makes in this novel until you reach the end. The story follows Anne, an 82-year-old woman in Scotland, slowly losing her memory as her grandson, Luke, a soldier in Afghanistan, returns home to unravel the secrets of her past. It's known she was a talented photographer, that she had a child--Luke's mother, Alice--with another photographer, Harry Blake, and yet, her talent never took off. Why? And is the self she hides and is slowly forgetting the same self that she is now?

The novel is ambitious, and short. It tackles themes of war, representation of history, families and their secrets, and realization. The image of light is pervasive and threads itself throughout the novel in many forms.

While I struggled through the first half of the novel, disengaged with the alternating narratives, the second half tied things together. In this case, hindsight is 20/20. It's important to see the whole picture, and once the metaphorical light was switched on, things came clearly into focus. Much like the photographs Anne has taken, the story has sharp contrasts, of light and dark. Scotland and Afghanistan. Young and old. Memory and loss. There are many dichotomies present that take you until the end to fully realize.

By no means is this a perfect novel, but it has something in it, some certain quality of lightness and fondness that stuck out at me. One particularly convicting passage said, "It isn't a world, Luke. People who read books aren't reading them properly if they stop with the books. You've got to go out eventually and test it all against reality." This novel presents the sad reality of life positioned against the hopefulness that comes with pulling yourself up by your bootstraps and setting off into the world, young, carefree, optimistic, and not yet illuminated.

3.5 stars -

This audiobook intrigued me more than I thought it would as at the moment often just have brain power to focus on lighter, exciting or sexier read but sometimes a story comes along that surprise me. I can't pint pont exactly what I enjoyed with this one but the writing was compelling

-

BABT

BABT

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b050zy4f

Description: A compelling new novel by two-time Booker finalist and internationally acclaimed author Andrew O'Hagan. For readers of Colm Toibin, Ian McEwan, Alan Hollinghurst and David Mitchell.

How much do we keep from the people we love? Why is the truth so often buried in secrets? Can we learn from the past or must we forget it? The Illuminations, Andrew O'Hagan's fifth work of fiction, is a powerful, nuanced and deeply affecting novel about love and memory, about modern war and the complications of fact.

Standing one evening at the window of her house by the sea, Anne Quirk sees a rabbit disappearing in the snow. Nobody remembers her now, but this elderly woman was in her youth an artistic pioneer, a creator of groundbreaking documentary photographs. Her beloved grandson, Luke, now a captain in the British army is on a tour of duty in Afghanistan. When his mission goes horribly wrong, he ultimately comes face to face with questions of loyalty and moral responsibility that will continue to haunt him. Once Luke returns home to Scotland, Anne's secret story begins to emerge, along with his, and they set out for an old guest house in Blackpool where she once kept a room. There they witness the annual illuminations--the dazzling artificial lights that brighten the seaside resort town as the season turns to winter. The Illuminations is a beautiful and highly charged novel that reveals, among other things, that no matter how we look at it, there is no such thing as an ordinary life. 1: Anne is beginning to forget things. But a ceramic rabbit stirs long-buried memories.

1: Anne is beginning to forget things. But a ceramic rabbit stirs long-buried memories. 2: As Anne's memory fragments at home in Scotland, her grandson Luke toils with his platoon in the fierce heat of Afghanistan.

2: As Anne's memory fragments at home in Scotland, her grandson Luke toils with his platoon in the fierce heat of Afghanistan. 3: In Helmand, Luke and his platoon find themeselves in danger. Meanwhile back in Ayrshire, Anne remembers her past as a photographer.

3: In Helmand, Luke and his platoon find themeselves in danger. Meanwhile back in Ayrshire, Anne remembers her past as a photographer. 4: Anne's obsession with her ceramic rabbit has been noticed at the sheltered housing complex.

4: Anne's obsession with her ceramic rabbit has been noticed at the sheltered housing complex.  5: Luke has a sense of foreboding as the soldiers leave the convoy to go sightseeing in Kandahar, while Anne's artistic achievements are about to be recognised.

5: Luke has a sense of foreboding as the soldiers leave the convoy to go sightseeing in Kandahar, while Anne's artistic achievements are about to be recognised. 6:As the Helmand mission begins, Luke is worried about his commanding officer Scullion's erratic behaviour. Meanwhile in Scotland, Alice responds to growing interest in her mother Anne's photographic archive.

6:As the Helmand mission begins, Luke is worried about his commanding officer Scullion's erratic behaviour. Meanwhile in Scotland, Alice responds to growing interest in her mother Anne's photographic archive. 7: After witnessing Scullion's horrific battlefield injuries, Luke has left the army. Back in Scotland he vows to help his gran track down her missing photographic archive.

7: After witnessing Scullion's horrific battlefield injuries, Luke has left the army. Back in Scotland he vows to help his gran track down her missing photographic archive. 8: Luke plans a trip to Blackpool in search of his gran's missing photographs, as well as answers to some of the mysteries in her past.

8: Luke plans a trip to Blackpool in search of his gran's missing photographs, as well as answers to some of the mysteries in her past. 9: Anne is on the road to Blackpool with her grandson Luke, who is determined to piece together the fragments of his gran's past.

9: Anne is on the road to Blackpool with her grandson Luke, who is determined to piece together the fragments of his gran's past. 10: Luke has left the army for good and travelled to Blackpool with Anne to locate her lost archive, along the way uncovering the tragedy which led to her giving up photography.

10: Luke has left the army for good and travelled to Blackpool with Anne to locate her lost archive, along the way uncovering the tragedy which led to her giving up photography. -

Fading Images

Look up Blackpool on the Internet. The largest seaside resort on the Northwest coast of England, it drew mainly working-class holidaymakers from the industrial North and Scotland, reaching its peak in the middle of the last century, when major stars would play its theaters, but it has not been able to compete with cheap fares to warmer resorts abroad. Blackpool has long been famous for its extensive illuminations that light up its promenades, piers, and miniature Eiffel Tower. The tarnished glamour of the resort in former days is an emotional point of reference in Andrew O'Hagan's latest novel, even though he does not take us to those particular illuminations until the very end. But the metaphorical associations of the title resonate throughout.

Most of O'Hagan's book is divided between the Ayrshire coast of Scotland (setting of his excellent

Be Near Me, one of whose characters makes a brief appearance here), and Afghanistan. The two principal characters are Anne Quirk, a former photographer who is now an elderly woman living in a retirement community, and her devoted grandson Luke Campbell, a Captain in the British army. I have to say it is a difficult book to follow at first. Anne is succumbing to senile dementia, and little of her conversation makes everyday sense. Though university educated and a thinker, Luke spends much of the novel with the soldiers in his armored vehicle, and the constant barrage of obscene insults in various regional dialects comes pretty close to unintelligibility. The Afghan scenes had a certain element of déjà vu for me, I think from my recent reading of

The Human Body by Paolo Giordano, but maybe it is simply that both authors took care to show it like it is.

Neither story is as simple as it seems. Anne Quirk has been a photographer in her youth, a true artist and something of a pioneer. The author implies that he was inspired by the Scottish Canadian photographer Margaret Watkins, although the biographies don't quite match. Anne's talent emerges gradually through O'Hagan's words, but seeing the pictures which were his inspiration adds an extra glow to the novel in retrospect. Most of Anne's thoughts now are centered on Blackpool, where she met her husband, Harry Blake, a war photographer and hero in his own right. It gradually becomes clear, though, that constructing stories is not merely a symptom of Anne's illness, but something she has been doing her entire life, professionally and otherwise. And when things go horribly wrong in Afghanistan, and Luke returns to Scotland, he too must shape some kind of narrative that makes sense of who he is and what he lives for.

I am somewhat in the air on rating on this one. There is much more in the book than I have described—for example, riffs on the secrets and resentments endemic to extended families—and at times I felt it lacked focus. But the gentle process of illumination, carefully letting the light in as a photographer does when developing a film, is one that I find quite beautiful, ultimately persuading me to round up rather than down. -

Man Booker Prize Longlist Strike #3. I'm a huge fan of this prize, and like many fans I've started to make my way through the long list, and so far it has been a disappointing experience.

I had such hopes that this one would break my horrible streak with the books on this list. And it started out so well. I loved the first chapter - the women, the writing - wonderful. And then. I turned the page to chapter two, and I honestly did not even understand much of what was being said, even though it seemed to be beautifully written. Here I go again. 50 pages and I'm out.

So what do I do now? The first three books I tried were by men, and maybe I'll have better luck with the women authors. Pretty please, with my fingers crossed for luck. -

I'm putting this down. There's nothing wrong with it, but I am over 100 pages in and not engaged with the characters at all. The minute I realized it was a slog, I decided it was okay to put down.

-

The title of this book refers to the Blackpool illuminations in a seaside resort in Northwest England, a place whose annual light show casts a rosier glow on the landscape than is actually present otherwise. The yearly spectacle, “’One million individual bulbs and strips of neon,’” the lights on the promenade are a metaphor to the illusion present in the lives of its main characters, and the artificial sunshine of their past. It’s a meditation on memory and mirage, fact and fiction.

There’s Anne, the 82-year-old woman living at a sheltered residence flat in Scotland, and suffering from dementia. Blackpool is a place of her young and robust years, one that is gradually revealed at the end of the story. At one time in the sixties, she was part of a revolutionary group of young British documentarian photographers. She remembers her past as like the Blackpool illuminations—a halo glow, especially when referring to Harry, the love of her life, a man who also taught her photography.

Anne’s grandson, Luke, a captain in the 1st Royal Western Fusiliers, has just returned from a failed mission in Afghanistan— to bring a turbine to the Kajaki dam, one that would help pump fifty-one megawatts of electrical power to the Afghan people--again the illuminations metaphor. The book highlighted Luke’s adventures with his fellow soldiers, getting high on weed, arguing about metal music, and dealing with a burnt-out, unbalanced commander. The mission went awry, and Luke alas, is suffering from disillusionment. In fact, he and his buddies believed that the virtual reality of video games was more real than desert combat.

Before joining the army, Luke was a scholarly young man who loved to read. This is a trait that he shared with his grandmother. His mother, Alice, has always had a distanced relationship with Anne. There’s enough family dysfunction to go around, and then there’s Anne’s primary helper, Maureen, a straw character, essentially, to bring out Anne’s secret past and the story of her photos.

At the start of the story, I was enchanted. O’Hagan had a knack for juxtaposing—no, almost surreally painting—a portrait of Anne’s dementia against the theme of the novel, which is the stories we tell ourselves to make sense of our lives, the narratives we construct—sometimes artificially—to reconcile the lives we chose to live. This premise, which is lucent and brilliantly rendered from the beginning of the story, hooked me immediately. However, once the story focused on Luke’s mission, it became inauthentic. The brio, language, brotherhood, and bonhomie, as well as the rage, ribaldry, and repartee of the soldiers became as artificial as the Blackpool Illuminations. I just didn’t buy it—it felt like O’Hagan did a shallow treatment of men on a mission, and gave us a theatrical version, one that may look good on the video games he talked about, but just as unreal. In fact, I thought it troubling that the author expounded on the curse of technology today—how these soldiers felt more battleborn in video games than in actual missions, and then turned around and gave the squadron just as much fakery, especially the heavy-handed reach of working-class dialogue.

O’Hagan utilizes contrast and opposition as a working device for the story, which underscores the theme, such as, in photography “to work with contrast not only to get at life but to enhance it.” The contrast between the video games and reality, and the disparity between lucidity and dementia, are woven into the premise. He also uses photography itself as a metaphor: “…he understood that new light isn’t good for old film,” meaning that the present distorts the past, and to mine the past through the lens of the present will reveal some self-deceptions.

Some of the novel worked for me, when it focused on Anne and the family story. But, as Luke’s commander too pithily said, “People who read books aren’t reading them properly if they stop with the books. You’ve got to go out eventually and test it all against reality.” The book periodically failed the reality test for me. -

4.5 stars? Oh, this one surprised me! Time will tell if I round it up or down, but the Illuminations was surprisingly close to clutchable. Andrew O'Hagan's novel is a heartwarming book that starts out as a sort of mystery. Not a mystery as a genre, but as "who and what is this book about and where is it going?". It is touching and sad and yes, I feel for the characters.

The Illuminations is primarily about Ann, an elderly lady living in a retirement home. She is estranged from her daughter but has a loving relationship with her grandson, Luke. Ann's story is told, or surmised by: her next door neighbor, her daughter and her grandson. It is a sweet and heart breaking all at one time. I love the relationship with the grandson and neighbor and hurt for the daughter. It is a story of lost dreams and misunderstandings as well as a story of discovery and forgiveness. Reflecting on this review makes me want to go back and re-read it to spend more time with the characters.

The main reason I am not giving The Illuminations 5 stars is that part of Luke's story takes place during the war with Afghanistan. I personally don't enjoy reading about any of the wars past WWII - Iran and Afghanistan especially. Although this story line builds Luke's characterization, it was my least favorite part of the book.

The audio narration was very well done as well.

As far as the Booker award goes: I do hope this one makes the short list. As with the other long-listed books I have read, I am afraid that even though I liked this one better than the juggernaut, A Little Life, I don't think The Illuminations will surpass A Little Life in the judges eyes. Both dealt with the discovery of a past life and the coping mechanisms necessary to continue after disappointments and tragedy and the hurt that one leaves in the wake of life's curveball. Yet, I think the Illuminations gets the point across more succinctly and with more hope in the end. -

The title of

The Illuminations has so many meanings in this book: it is a festival in Blackpool, England in which strings of white lights are illuminated all over the resort town to mark the end of the summer season; it refers to photographic techniques (and especially how chemicals can be used to fudge the realism of images); it can mean the tracer fire used in combat to mark an enemy's position; and it can mean an epiphany – whether a sudden realisation of one's own failings or moments of lucidity for someone with worsening dementia. It would almost feel too clever to use this title for a book that covers all of these topics if it wasn't so very well written; as it stands, this is a very illuminating novel.

The Illuminations jumps between multiple points-of-view (sometimes even within a single paragraph), and is divided into alternating sections as it follows Anne Quirk – an old Canadian-Scottish woman with dementia, a fascinating past, and hidden secrets – and Luke Campbell – Anne's grandson, a Captain in the British Army, currently deployed in Afghanistan. In her youth, Anne was a noted photographer, and from the time Luke was a child, his gran had recognised the boy's potential to see the world as she did – deeply – and she took on his early education: collecting shells and sea plates together for their Dickensian “conchological cabinet”; reading the same novels throughout his school years; or advising him:

“The colour red doesn't actually exist. It only exists as an idea in your head. Always remember that. You create it yourself when your imagination meets the light.”

Light is everywhere in this book, as is the notion that reality is created within our own heads. As the book begins, Anne is in a seniors' independent living facility, and as her dementia worsens, her neighbour Maureen begins to take care of Anne so she won't need to be moved to an actual nursing home. At sixty-eight, Maureen is the youngest resident in the facility, and by assuming small responsibilities (offering to buy the daily milk, vacuuming the common areas, being a busybody in Anne's life), Maureen is the happiest she has ever been in her a life (a fact she refuses to confess to her children because she finds it more enjoyable to pretend to be miserable). Sometimes Anne can carry on an intelligible conversation, and sometimes she mixes up people and the era she's in (I shouldn't even mention the ceramic rabbit Anne wants Maureen to cook for, but it does come up again later):

(Anne) appeared to be trying to climb out of herself before it was too late. Whatever vessel Anne had sailed in all her life, it began to drift and that was the start of it all. She rolled into a darkness where everything old was suddenly new, and when she returned to the surface her life's materials were bobbing up around her.

On the other side of the world, Luke – who joined the army in order to “find” his own father (a British soldier who died while policing “the Troubles” in Northern Ireland when Luke was a boy) – is engaged in a war he's not certain he believes in any longer. These sections in Afghanistan were fascinating and exciting, and more than anything, they just felt so real: the oppressive heat and the boredom of spending longs hours in the belly of an armoured vehicle, interrupted by scenes of panic-inducing danger, surrounded by hard-talking kid-soldiers who are itching to see real combat. The platoon leader Major Scallion notes:

“You all think you know the terrain 'cause you've seen it playing video games.” Half his face lit up as he smoked the joint and sniggered. “But don't give me points man; give me body count any day.”

After an interesting observation that video games today are the modern army's most effective recruiting tool (and noting that the operating controls in new American tanks are exactly like videogame joysticks – how backwards is that?), we see a scene where Scullion and Luke take a sight-seeing trip, with two jeeps full of soldiers smoking confiscated Afghan weed, blaring death metal from their stereos, racing past sand-choked poppy farms in a cloud of dust and noise: this felt like it belonged in Mad Max, but I 100% believe this happens out there. The end of this trip and its consequences eventually cause Luke to lose faith in his mission, nationalism, and his life's purpose.

In the end, Luke returns to Scotland and decides to take his gran on a trip to Blackpool – the place where Anne had met his grandfather Harry – in order to help her remember her happiest times; in order to help him forget Afghanistan. Along the way, we meet Anne's daughter (Luke's mother) April, and Maureen's family, and consistently, we see people who don't believe they were loved enough, but who can't bring themselves to give more than they've received. This is a book about memory and keeping people alive through the stories we tell (even if these are just lies we tell ourselves – even photos can be altered to match our visions of reality) and it's a book about the role we must each play in forming our own character. At times exciting and funny and thought-provoking, The Illuminations is a perfect mix of story and craft, a knockout read. -

As a man who spent many of his formative years in direct contact with his Grandmother, I was at once intrigued with this story. It is the story of a woman, who is in the process of reliving her past life, thanks in large part to the onset of dementia. Juxtaposed atop this, is the story of her Grandson who is currently completing a mission in Afghanistan. At first I was apprehensive as to how the two narratives would appear on the page - two totally different voices, mindsets, experiences - but this is but one example of the brilliance that is Andrew O'Hagan.

The story of families is at the core of this novel. The histories that families sometimes 'create' as a defence mechanism for their survival [personal and as a unit] reverberated throughout. A strong matriarchal presence drew me like a moth to the flame, and I was soon enshrouded in a mystery that might have been lifted from the pages of my own history. Anne Quirk spends much of the novel mythologizing Harry Blake. She was a brilliant photographer, and her affair with this larger than life married man consumed much of her early life. When she is jilted, she gives up her career and all but disappears. All the while she continues to build up this nearly god like presence of Harry. My own Grandfather was killed while in the line of duty as a motorcycle policeman.

My Gran was 31 and had two sons, aged five and seven. I only knew of my Grandfather through the stories and newspaper clippings that I was shown over the years, and through the stories that would eventually emerge from my Grandmother's own mouth. He too seemed larger than life: His matinee idol looks, his artistic talents, [a newspaper clipping showed the police force presenting a young boy with a new red wagon after his had been stolen, one that had the lad's name emblazoned on the side, courtesy of my Grandfather] and the tragedy of the night of his death. My own Father had few memories which at the time seemed natural to me. In the twilight of my Grandmother's final years, she revealed to me that all was not as it had seemed. She saw so much of her late husband in me, and I to this day believe that it accounted in part for the strong, intrinsic bond that we shared with one another. I walked like him, I had his eyes, I possessed the same single mindedness [as an introverted solitary person, my personal needs have always been my first order of business] that in her eyes, as a wife and mother might have been interpreted as greed and selfishness. She saw so much of him in me, but she also saw herself - perhaps even more so! She spoke of her trials and tribulations with me - it was a conspiracy of sorts between a Grandmother and a Grandson. She intuited that I had plenty of secrets of my own. This story arc had my undivided attention.

But I digress,,,,,

Luke is witnessing first hand the atrocities that come with war. He begins to doubt his own beliefs, and when he realizes that his commanding officer shares these same doubts, he instantly smells the trouble that the entire company is in. They are supposed to be the leaders of a group of what are essentially gamer- teenaged boys. Things do indeed go terribly awry, and yet miraculously he is able to return home and leave the war behind. The language and imagery that O'Hagan imbues this part of the story with is at once jarring as it is testosterone riddled. It is a markedly different world from Anne's...... or is it? Luke is forced to test his moral beliefs. An educated, well read, sensitive young man with an ability to see beyond the mundane everyday existence of the war, everything he has come to believe about the world is being tested before his very eyes. He is relearning himself from the inside out. Back home his Grandmother is reliving and relearning her own equally tragic history.

Before she is placed in a retirement home, Luke and his Grandmother return to Blackpool. to a room that Anne has been renting since the day her affair collapsed around her at her feet. It is only here, and by means of letters and photographs that Luke has taken to studying, is he, and we the reader, finally able to piece together the truth behind Harry, and how the realities have reverberated across the entire family tapestry. Anne's daughter has always felt like an outsider looking in, especially where the relationship between Anne and Luke is concerned, and it is only in the final pages of the novel is she able to find hew own sense of self, and with it a delicate peace with the promise from her Son that they will work through all of it together.

It has inspired me to revisit my own family history - to find the wooden chest that contains the pictures and stories of who I am and how it all came to pass. Thank you Andrew O'Hagan for defining 'family' in such an evocative manner! -

The Illuminations Andrew O'Hagan

5 Stars

Man Booker Prize Long List 2015

I must start of by saying how much I loved this book, the characters were well developed, flawed and alive, throughout the book I was either rooting for them, relating to them or berating them for their behavior to say I was invested in the outcome is an understatement.

The premise of the story is how we one woman (Anne) has kept her real self hidden from her family for years, now in a nursing home with advancing dementia the past she has so carefully hidden is slipping out in unguarded moments when the past is more real to her than the present.

While Anne is losing her present her grandson Luke a soldier in Afghanistan is wishing he could lose his, while her daughter Alice feels a burning need to understand the past so she can make sense of who she is and move on with her future.

This is a story about the damage families can inflict on each other just by being who they are and the only way to move forward is to reconcile yourself with the truths of the past.

The writing is beautiful here are a couple of my favourite quotes;

"She came quite regularly to see him and always left feeling better, but it annoyed her the way he found every problem so familiar. It was clearly part of his effort at cheerfulness and she found herself hoping he was a secret drinker"

"Colour is light on fire"

"Even as the chill of the icebox caressed her hand"

These quotes relate to everyday events talking to the doctor and getting ice cream from the freezer but as you can those simple acts are transformed into something else by the use of language. -

'It was wrapped in brown paper and tied up with string. I had no idea what was inside, but I had to promise not to open it till she died.'

And he kept his promise, did journalist and later gallery owner, Joseph Mulholland. Until he opened that gift to him he had no idea who she had been. She never spoke of it during their friendship. At the time she passed over the present to him Joe's daughter was battling leukaemia so he had much on his mind as he stashed the parcel away in the back of a linen cupboard. It was later, in 1969, when his neighbour did finally succumb to mother time, that Joe, who in the meantime had been invited to be executor of her will, remembered his vow from years before. What he found when he retrieved that package eventually bought Margaret Watkins back from obscurity - so much so that in 2013 Canada Post commemorated her on a stamp issue.

He thought he knew her back story pretty well. Margaret and Joe had become firm friends and on many occasions, over the years, had talked long into the night about their lives - but she never let on. To him she was the sweet elderly lady who shared the street with him. Nothing in her tales prepared him for what was revealed the day of the opening of her gift to him; her gift to two nations. Inside were thousands of photographs and negatives - a treasure trove of memories, a treasure trove of art. Joe Mulholland is now in his seventies and is Margaret Watkins' champion; the keeper of her flame. Thanks to his efforts to bring her in from the chill of obscurity Watkins is now recognised as being '...a highly distinguished and important figure...' in the story of photography. It is significant that two countries, Canada and Scotland, claim her as their own as galleries line up to display her oeuvre - an oeuvre partially contained in that package.

Watkins was born in Hamilton, Ontario in 1884. In 1913 she moved to Boston, gaining employment at a photographic studio. From that point on the art became her life - until circumstances took a more notable future in it away from her. But even after she ceased snapping, later events showed it was never far from her mind. She took photography seriously from the start, enrolling in Clarence H White's Maine Summer School. White was a notable practitioner and not adverse to having relations with his students as well. That may or may not have been the case with Margaret, but he quickly caught on that she had the chops to make a name for herself and became her mentor. This led to one of her career setbacks. He willed her his artistic legacy, but was challenged in court by his widow. Bizarrely it was found that Margaret was entitled to his photographic images but she was ordered to sell them to the spouse for a fraction of their worth.

By 1920 Watkins was the editor of a leading journal as photography became increasingly well regarded as an art. She was also freelancing for advertising agencies. She taught her skills as well, passing on her knowledge to others who, like her, could see photography as their calling.

But then family called and she felt obliged to leave all she had achieved behind her and start anew across the Atlantic. Four aged aunts were in dire need of a carer and Margaret felt obligated. For a time she could continue on, establishing herself in Glasgow and taking on commissions that saw her travel around Britain and across the Channel. As the aunts became even more frail, though, she was forced to restrict herself to snapping industrial Glaswegian landscapes and the city's denizens.

After Joe opened his package he wondered if more lay in her large residence opposite. It did - an incredible cache was found, much of it now housed in Mulholland's own shop-front for her talent - Glasgow's Hidden Lane Gallery. He found advertising images, her work in social commentary and luminously lit nudes. He also unearthed an image of her as a young lady and found it difficult to reconcile this '...imperious...' self portrait with '...her dark hair tied in a chignon, looking down her nose, regally, at the camera.' with the old dear of his friendship.

The images he uncovered proved that Margaret W was a most versatile practitioner. Her early still lifes, such as the one featured on the Canadian stamp in her honour, 'The Kitchen Sink' (1919), caused some controversy amongst critics. Most, though, were of the opinion that, what she produced with these, were '...composed like a painter and tended to see ordinary things as very beautiful.' There were also her portraits of the celebrities of the day taken in her Greenwich Village studio, including that of great composer Rachmaninoff. After being removed from the New York scene she was more limited in what she could produce. Now it tended to be more the everyday recording of what she discerned around her. Eventually her nursing duties made even this difficult and she more or less gave the game away, disappearing from view until her recent rediscovery. But her moment had really passed the day she left the US.

Outwardly, according to Joe, she remained chipper till the end. He did find evidence in her abode that all was not as it seemed. There was a scribbled note that gave an insight to the real condition of her mind, to the effect that she '...was living in a state of curdled despair...I'm doing the utmost to cope with a well-nigh hopeless situation.' He also found she had packed her bags to return to the scene of her days of photographic pomp - to return to New York.

Anne Quirk is Margaret Watkins. The sublime novel, 'The Illuminations', has bought Watkins' story back and to a wider audience in the guise of a fictional protagonist. Anne has dementia. Her memories of the past are fragmentary. She is struggling to remain semi-independent - not in a fine house next door to Joe M, but in supported accommodation. Here there is also a neighbour who takes her in hand, helping her through the day so she can cope. Maureen has had her troubles too, but she has commenced to piece together Anne's back-story. Anne's aggrieved daughter Alice fills in some gaps too, but it is with conflict-damaged soldier Luke, her grandson, that she shares her greatest bond. Through Luke, author Andrew O'Hagan presents all the ugliness of our current Middle East involvements. Luke has returned from Afghanistan battered and bruised mentally. He takes to the Mulholland task, once he discovers a similar trove of photographic images, to bring Anne back in from the cold. So it is potentially win-win. Anne's legacy gives him something to focus on, he gives her one final escape from the fog that is enveloping her mind.

And then there's Harry, her mysterious lover from the post war years who encouraged her with her artistic pursuit. When it really counted, though, he left her in the lurch. A terrible tragedy followed that caused Anne to lose much of her will for a while. In her memory Blackpool, where her liaisons with the married beau occurred, was the place where she was happiest. So, at the end, that's where Luke takes her. In doing so the remainder of her story is unravelled. Even the Beatles get a cameo. The pair arrive in time for the famous illuminations that light up the resort each year. By now the reader realises that the future of both these characters is on the up and up, even if poor Anne no longer has the wherewithal to fully realise that. This is helped immensely by a letter from a Canadian gallery, one that had cottoned on to her historical worth as well.

Through Anne Quirk, Andrew O'Hagan, together with good neighbour Joseph Mulholland, have seen to it that a champion of early women photographers has re-emerged and taken her rightful place. As for the novel itself, it is a fine and worthy book. By the end it is, as well, a compelling read. It was long listed for the Man Booker, but sadly didn't make the final cut. Pity that. O'Hagan's ultimately very moving and positive tome is thoroughly recommended by this reader. -

This is a book about memories - real ones and false ones. It follows two main characters - Anne Quirk, an elderly woman living in sheltered housing and suffering from Alzheimer's, and her grandson, Luke, an army captain serving in Afghanistan. The novel is full of clever metaphors and illusions to the past and to people's memories and histories, not least the illuminations themselves - Blackpool's - and the seaside town itself plays a major role.

In addition, Anne's past as a talented photographer is constantly alluded to and shows the powerful role that photographs play in our memories.

For most of the book, O'Hagan alternates between chapters featuring Anne's life in her sheltered housing block and the very much grittier sections featuring Luke's experiences in Afghanistan. What shines through is the author's wholehearted sympathy for all his characters. -

"Masking is a technique whereby you hold back some of the light." Some of the light is being withheld by each character in this book, either by their own inability to face reality or by the march of time. The Illuminations is a novel of today. Anne, in her 80's and gradually going under due to dementia, has been living semi-independently in a sheltered home protected by her neighbor to avoid being placed in "better care." Her life as a photographer taught her to look beyond the surface ("see the truth, not just the paint"), a quality she has instilled in her grandson Luke. Their relationship has always been close, unlike that of Anne and Luke's mother, Alice. Alice, to keep track of her mother, relies upon Anne's neighbor, Maureen, who also has complicated relationships with her own offspring. Complicated relationships and enhancement of reality play a large part in the narrative.

The scenes featuring Luke, deployed in Afghanistan with an Irish regiment, are among the most harrowing I've read in literature about the current wars. The Boyz, who mostly are young, adept at Play Station II, are eager to engage and prove their skills, and totally undone when it actually happens. Each is so realistically portrayed that their personalities are distinct and haunting. -

Unreadable. I slogged through a third of this book before I had to put it down and move on with my life. I guess he's been nominated for some prestigious awards for past works, but I couldn't get into this one at all - actually found it difficult to read. The jolting style of narrative and dialogue was so hard to follow, hard to keep the characters straight, the military jargon in the Afghanistan section was too obscure for me to catch what the characters were meant to be saying. Its a shame because I thought from the blurb that I would find it really interesting - I like photography, history, women's stories and Scotland, and I was really looking forward to it. But nope :(

I received this book as part of the GoodReads First Reads giveaway program - thanks anyway! -

A nice, straightforward book without fireworks or any twists and surprises. A nice book to pass the time, but I'm not sure what one of the central characters' story had to add to the whole thing.

-

At first you think this is a story of the slow decline of a life through dementia and told in a very odd style - without the normal structure of reported speech -and you wonder why we need to have such a detail description of the butchery that is war in Afghanistan. But the story reveals much more about the way we have and do live our lives. The importance of neighbours to us, the secrets families hide from each other and love that tend to suppress for our family. It is also a story of healing.

Glasgow, Blackpool, Canada, Afghanistan,Selly Oak Photography, secret love affairs, neighbours, social cohesion and all beautifully written. -

Anne Quirk is elderly, a onetime famous documentary photographer, and now her memory is failing. Her relationship with her daughter is troubled and her grandson, Luke, is serving in Afghanistan.

The account of his time there (which does not end well) is one of the most dramatic and yet down-to-earth, and character driven that I have read. The members of his unit and especially Major Scullion, stick with you long afterwards. And the sadness and slughter.

Luke returns to Scotland and decides to take Anne to Blackpool to see the lights. There, secrets, especially concerning her relationship with her beloved Harry, are revealed.

Memory, secrets, ideas and war and some remarkable writing. -

Two stories about members of different generations of the same family. Couldn't develop any interest in either. Stories alternate in first half of the book before coming together but still not much develops in ways of insights or plot. Even the dialogue of the grandson sounds different and hence not believable in the latter chapters. Am fairly sure I picked up this book after reading a rave but now forgotten review. Much like others, the reviewer must have got something out of this that I didn't.

-

From BBC Radio 4 - Book at Bedtime:

Andrew O'Hagan's novel follows 82-year old Anne Quirk, a forgotten pioneer of documentary photography who lives in sheltered housing on the west coast of Scotland. A planned retrospective stirs long-buried memories and leads her grandson to uncover the tragedy in her past which has defined three generations.

Abridged by Sian Preece

Reader : Maureen Beattie

Produced by Eilidh McCreadie. -

Liebevoll umsorgt von ihrer Nachbarin Maureen lebt die betagte Anne Quirk in Lochranza Court, einer Anlage für betreutes Wohnen an der schottischen Westküste. Bisher hat Maureen mit großem Einsatz die Fassade aufrecht erhalten, dass Anne selbstständig leben kann. Wegen zunehmender Demenz wird ihre Nachbarin bald in ein Pflegeheim ziehen müssen. Die erheblich jüngere Maureen, körperlich und geistig fit, flüchtete vor dem verminten Gelände ihres Familienlebens in die Wohnanlage. Den Ideen von Tochter und Enkeln kann und will sie nicht mehr folgen.

Anne steckt voller Überraschungen, so muss sie als Kind eine Zeit lang in Kanada und später in New York gelebt haben. Bis heute sieht sie ihre Stadt mit den Augen der Fotografin, die den Lichteinfall beachtet und einen Bildausschnitt wählt. In klaren Momenten erzählt Anne von Harry Blake, ihrem persönlichen Kriegshelden, der ihr den Weg zum Beruf der Fotografin ebnete. Harry und sie trafen sich in Blackpool, dem legendären Urlaubsort der britischen Arbeiterklasse. Immer häufiger jedoch holpert Annes Orientierung und sie glaubt, gerade jetzt zu einem Fotoauftrag aufbrechen zu müssen. Zur Sicherheit hat Anne Harrys Lebenslauf zur Hand, um auf Fragen nach dem Mann auf dem Bild in ihrer Wohnung antworten zu können. Nicht Vergesslichkeit scheint ihr Problem zu sein, sondern Einsamkeit, weil sie in ihrem Alter keine Gesprächspartner mehr auf Augenhöhe findet.

Annes schwieriges Verhältnis zu Tochter Alice beruht u. a. auf Annes Überweisungen nach Blackpool an Leute, die Alice nicht kennt. Zu Alices Sohn Luke Campbell dagegen hat Anne eine beinahe symbiotische Beziehung. Er verstand schon immer ihre Fotos; in ihm sieht sie eine künstlerische Begabung. Während Lukes Schulzeit hat die Großmutter mitgelesen und mitgelernt, so dass er heute sein Leben in ihrem Bücherregal wiederfindet. Luke kehrt gerade vom Einsatz in Afghanistan zurück. Durch Nachlässigkeit der Verantwortlichen, einer davon Luke, geriet seine Einheit in einen Hinterhalt, es gab Tote und Verletzte, auch unter Zivilisten. Demnächst müssen sich Luke und sein Kamerad Scullion dafür vor Gericht verantworten. Als Leser erlebt man Lukes Afghanistan-Einsatz so ernüchternd mit, als säße man neben ihm im Transportfahrzeug und läge mit ihm im Staub. Annes Erinnerungen an Schottland nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, der Tod von Lukes Vater in Nordirland und Lukes Kriegs-Erlebnisse scheinen an einem zentralen Punkt zusammenzulaufen. Anders als die Generation vor ihnen, die nach einem Krieg auf Frieden hoffen konnte, reiht sich für Männer wie Scullion seit dem Falkland-Krieg eine endlos scheinende Reihe von Kriegen aneinander.

In der Zeit bis zu seinem Disziplinarverfahren will Luke mit Anne nach Blackpool fahren, um mit ihr die legendäre herbstliche Illumination zu erleben. In Blackpool warten warmherzige alte Freunde auf Anne und zu Lukes Überraschung spürt er eine Geschichte auf, die Anne bisher nicht erzählen wollte oder konnte. Sie hatte damals in Blackpool ein winziges Appartement gekauft, das noch immer für sie bereitsteht. Von der Mutter der heutigen Besitzerin sorgfältig bewahrt, finden sich darin ihr Vermächtnis als Fotografin britischen Alltags – und Zeugnisse ihres nicht erzählten Lebens. Darin stößt Luke auf seine persönliche Geschichte und erlangt einen völlig neuen Blick auf seine Mutter. In einem Interview mit Globe and Mail berichtet O’Hagan, dass er Anne Quirk nach dem Vorbild der vergessenen kanadisch-schottischen Fotografin Margaret Watkins (1884-1969) und ihres Werks schuf. Wie O’Hagan Watkins entdeckte, das ist eine eigene Geschichte …

Die Symbolik von Licht und Erkennen harmoniert perfekt mit dem Leben einer Fotografin, deren Ruhm bis nach Kanada gedrungen ist. Krieg, Demenz, Einsamkeit, Lehr- und Wanderjahre, anfangs wirkt es, als verknüpfe Andrew O’Hagan beinahe zu viele Themen miteinander. Feinsinnig beobachtet, mit hinreißenden Figuren, entstand daraus ein zu Herzen gehendes Buch, das schon jetzt zu meinen Jahres-Highlights zählt. -

“The bobbing about of supportive or colliding groups, and the individual's life within them, has been O'Hagan's long preoccupation.” (

https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/...) I was inspired to read this book after reading ‘Mayflies’ which to some extent focuses on the ways in which individuals support or collide in relationship, especially when the going gets tough. I really liked that book.

This novel runs two main storylines. Luke Campbell is a 30ish army captain leading a squad of Royal Western Fusiliers in Afghanistan. His story alternates with that of his beloved grandmother, Anne Quirk, a woman stricken with growing dementia who is living in the Scottish town of Saltcoats. Luke comes from a military family. His father was a British soldier killed in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, and he enlisted as a way of connecting to a man he barely knew. Anne was once an avant garde photographer but gave this up many years ago. Apparently her character (in terms of art) is modelled on Canadian photographer Margaret Watkins who Watkins was apparently an acclaimed photographers in North America around the turn of the 20th Century, but she gave it all up, moving to Glasgow in 1928 and never returning home. “Watkins came to Glasgow in 1928 to visit her aunts, intending to stay for a year, but remained until her death 41 years later. Her work as a photographer was unknown in Scotland and not long before her death she gave a box to her neighbour, Mr Mulholland, on the condition he did not open it until after she died. It contained more than 1,000 photographs, many with exhibition labels, and among them were some of her New York kitchen.”

(

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-...

https://www.all-about-photo.com/photo...)

Luke has returned from Afghanistan after a catastrophic deployment in which one of his young soldiers died.” He is bitter, explaining to his mother:

There’s no nation, Mum. There’s only people surfing the Net … It’s a game, Mum. A great game. We only believed in it for as long as it lasted. I love my country for its hills and its inventions, not for its sense of injury, not for its sentimental dream that there’s nobody like us.

“The Great Game” usually describes British and Russian 19th-century imperialist manoeuvres in Afghanistan and elsewhere – here, Luke uses the term ironically: nationalism, in his view, is a delusion.” (

https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2...)

I’ve been reading this thinking about the recently publicised alleges atrocities of Australian SAS soldiers in Afghanistan. I’ve been thinking both about what a stupid, terrible war that’s been and how the process of becoming a soldier must almost inevitably involve some brutalisation or numbing to the things that happen. In the case of Luke and his fellow soldiers, they are en route protecting the journey of a piece of hardware when a stop in a village goes badly wrong. I don’t want to spoil the tension by saying more – he creates the scene really well. O’Hagan is said to have spent a lot of time with soldiers who have seen “action”; he “relies on imagination, empathy and members of the Royal Irish Regiment who, according to his publishers, “have been answering his questions since he began The Illuminations.” The military insights (“The time to start worrying on a mission is when the boys are being too nice to one another”) and dialogue, which fizzes with derangement and tenderness, shows he listens closely.” (

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-en...)

In one interview, it was stated: “O'Hagan has been a Unicef Ambassador for 15 years. He went to Afghanistan in 2013. "I had come with no agenda, but could quickly see that I'd arrived in a country caught in the middle of some insane politics, and the war was something we not only appeared to be losing, but that we didn't understand."” (

https://www.smh.com.au/national/scott...) Apparently he wrote an essay in 2013 for the London Review of Books about children in Afghanistan; an earlier piece of 2008 described the experiences of British soldiers in Iraq. “The actual battle for the Kajaki dam, which took place in February 2007, and US air strikes on villages where weddings were taking place and civilians were killed, inform the novel’s war scenes.” (

https://www.theguardian.com/books/201...)

I thought he wrote very effectively about war and about the youth of its main participants. “For the new generation of soldiers, O For the new generation of soldiers, O’Hagan writes in one of the novel’s persistent themes, actual warfare seems less real than the combat video games they grew up playing: “Younger soldiers often thought they knew the battleground; they saw graphics, screens, solid cover and . . . guns you could swap. . . . They saw cheats and levels . . . and the kinds of marksmen who jump up after they’re dead.” (

https://www.washingtonpost.com/entert...)

Luke spends time with his grandmother when he returns to Britain and the novel moves into a space where they travel together to Blackpool to the annual festival of Illuminations. Blackpool is where Anne kept a room in a guesthouse for a long period of time. Blackpool is illuminating (sorry – it is a bit of an obvious metaphor) in terms of Anne’s history and family. One reviewer called out the folus on light: “Lights are burning everywhere in the dark world of Andrew O’Hagan’s impressive new novel: snowflakes pouring from a street lamp “like sparks from a bonfire”; a single tiny lightbulb shining in a doll’s house; the “constellation of death” that is the light show of rocket-fire in a hillside war at night; light falling on ordinary objects in a kitchen sink to make an artwork; the “illuminations” bursting into life in Blackpool. “Colour is light on fire,” says a woman to her grandson, a woman who has spent her life “looking at objects and the way the light ... changed them”. And then there’s the light of truth, the book’s underlying theme: erratic, patchy, often unwelcome, and hard to get at – because “life had been rearranged, and always is”.” (

https://www.theguardian.com/books/201...)

I liked this book but felt that the weight and awfulness of the events in Afghanistan kind of dominated Anne’s story and the last section felt a bit hasty and too easy. The two narratives felt unbalanced. Having said that, I really enjoyed reading it and will seek out more of his books. -

"The Illuminations" is one of the best psychological realist novels I've read in a while. O'Hagan is one of those stealth writers who have a disarming style but whose work dig into major issues of aging, loss, war and family. He's Scot critic and journalist whose novel "Our Fathers" was also a beautiful novel about different generations meeting up in contemporary challenges. The Illuminations is a novel about a family's past, memory and trauma, as well as of who we are and the stories we tell ourselves as Time washes over us without our sanction. O'Hagan captures a dissolving mind and a lost soul as his major protagonists. He has the unique ability to capture a room like few authors. "She'd been bullied by the stories that surrounded her" is one of those perfect phrases that lit up the "ordinary lives" of his characters. O'Hagan could make a rainy lunch fresh and new. O'Hagan also captures gruff dialogue quite well in Afghanistan and shifts to the mannered and subtle changes in behavior back in Britain. O'Hagan is an author to savor. His narratives of family and generations may seem standard but they're always written with a linguistic shine, as well as clear-eyed focus on the major issues of the age deeply connected to the past. Each well-paced page of his novels will make you crave another.

-

The Illuminations blends two jarring worlds - a Scottish care home, and the battlefields of Afghanistan. It's to Andrew O'Hagan's credit that despite that this novel never comes off the rails.

In the care home we meet Anne - an Octogenarian whose mind is disintegrating under the growing grip of dementia; in the battlefields is her grandson Luke, struggling with his superior officer as well as the mistrust and outright hostility of locals.

There are other fully-formed characters too. Fellow care home resident Maureen befriends Anne, and increasingly acts as a conduit between her and Luke and the rest of her family.

Families are flawed here. Luke is close to his grandmother, but his mother has a distant and difficult relationship with Anne; Maureen's connections with her children are similarly strained.

And that same mixture is apparent in Luke's surrogate army family too - there a closeness to his juniors, but his relationship with his superior goes sour with terrible consequences.

At the heart though is a mystery. Anne's occasional bursts of lucidity reveal details of a life as a pioneering photographer, and of the man she loved.

There is a connection to Blackpool, but The Illuminations of the title also refers to the sporadic lifting of the fog in Anne's mind.

O'Hagan writes beautifully, and the sections in the care home focusing on Anne and Maureen are tender and delicately done.

I found the passages in Afghanistan less successful. O'Hagan insists on peppering them with army banter, which to me sounded a little forced and false. There is power in the events that overtake Luke and his platoon, but the relationships seemed less convincing than in the quieter care home setting. A final confrontation with his superior officer teeters on the edge of melodrama.

Anne's dementia also seems perhaps more benign than it would really be. I would guess she would be more confused and angry in the early stages than it appears, but I am willing to believe that every case is different.

This book, of course, has deep sadness at its heart, but as Luke and Anne's stories merge towards the end in a final road trip to Blackpool, there is warmth and solace too.

Any book which focuses on war for part of its time is of course political, but the strength of The Illuminations lies in the intensely personal focus of the final section. -

I thought this story had SO MUCH POTENTIAL. But it fell so flat for me.

Things that I assume we're supposed to be profound, came across as nonsense instead. It felt like the story was trying SO HARD TO BE DEEP and I just couldn't connect with it.

There were too many people and too many side stories and I guessed most of the reveal very early on.

I'm all for family drama, but this was just a giant piss-pot of lack of communication. Maureen and Alice were suuuuuch annoying characters. Oh man. This was just not for me. -

I’m not too sure how I feel about this book. I liked it, it felt a bit like I was meandering through someone else’s memories, which I suppose was the point. I did keep waiting for something momentous to happen though, and it never did.

-

3.5 stars. I'm a huge fan of Andrew O'Hagan but I didn't find this book as engaging his other books. The 2 intertwined stories didn't gel that well and felt disjointed. I liked the way he incorporated the character Mark from 'Be Near Me', into the desert storyline - nice touch!