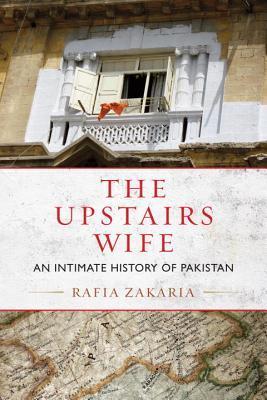

| Title | : | The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0807003360 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780807003367 |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 264 |

| Publication | : | First published February 3, 2015 |

An Indies Introduce Debut Authors Selection

For a brief moment on December 27, 2007, life came to a standstill in Pakistan. Benazir Bhutto, the country’s former prime minister and the first woman ever to lead a Muslim country, had been assassinated at a political rally just outside Islamabad. Back in Karachi—Bhutto’s birthplace and Pakistan’s other great metropolis—Rafia Zakaria’s family was suffering through a crisis of its own: her Uncle Sohail, the man who had brought shame upon the family, was near death. In that moment these twin catastrophes—one political and public, the other secret and intensely personal—briefly converged.

Zakaria uses that moment to begin her intimate exploration of the country of her birth. Her Muslim-Indian family immigrated to Pakistan from Bombay in 1962, escaping the precarious state in which the Muslim population in India found itself following the Partition. For them, Pakistan represented enormous promise. And for some time, Zakaria’s family prospered and the city prospered. But in the 1980s, Pakistan’s military dictators began an Islamization campaign designed to legitimate their rule—a campaign that particularly affected women’s freedom and safety. The political became personal when her aunt Amina’s husband, Sohail, did the unthinkable and took a second wife, a humiliating and painful betrayal of kin and custom that shook the foundation of Zakaria’s family but was permitted under the country’s new laws. The young Rafia grows up in the shadow of Amina’s shame and fury, while the world outside her home turns ever more chaotic and violent as the opportunities available to post-Partition immigrants are dramatically curtailed and terrorism sows its seeds in Karachi.

Telling the parallel stories of Amina’s polygamous marriage and Pakistan’s hopes and betrayals, The Upstairs Wife is an intimate exploration of the disjunction between exalted dreams and complicated realities.

The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan Reviews

-

The title is misleading,this is not really an intimate history of Pakistan.And most Pakistani men make do with just one wife,these days.

Rafia Zakaria writes regularly for the Pakistani newspaper Dawn,and I find her columns interesting.Women's issues are a major theme of her writing.

I was,therefore,keen to read her book.I read it in one sitting,though it left me with rather mixed impressions.

It is an interesting experiment,juxtaposing the story of her aunt,whose husband takes a second wife because of her childlessness,with some important events in Pakistan's history,till the assassination of Benazir Bhutto in 2007.

At times the book did remind me of Kamila Shamsie,who also writes about life in Pakistan's mega city Karachi,and the disillusionment and alienation of the Muslim migrants from India,and their descendants.

Karachi bursts at the seams,and frequently descends into unimaginable violence.Rafia captures the magnitude of the city's problems pretty well.But as far as her analysis of events in Pakistan's history is concerned,it isn't particularly balanced.

At times she presents the perpetrators of the violence as the victims.The migrants from India may feel alienated,but they also have much to answer for,when it comes to Karachi's violence.

The story of her aunt,whose husband takes a second wife,because of her childlessness is not particularly compelling.

Two Pakistani wives,living on separate floors,and never ever speaking to each other for years,is scarcely credible.Such a house could only become one thing,a battleground.

The book starts with the assassination of Benazir Bhutto,and has a good deal about her,as the first woman to lead a Muslim country.

Mercifully,at least,she is not glorified needlessly and her flaws and corruption are acknowledged.

Despite its flaws,Rafia's debut book was an interesting effort,which kept me turning the pages. -

When I brought this book, I was expecting something along the lines of Fatima Merissini. This book is not that.

What this book is a chronicle of a family life in Parkisten after Partition, Zakaria’s family moved to Pakistan because of the anti-Muslim climate of India. Zakaria’s family history, in particular, that of her childless aunt whose husband takes a second wife. The personal conflict in the family is also shown in contrast to the unfolding political and societal drama, as Pakistan’s government tightens control over women.

In many ways, Zakaria’s story is like Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, and considering that Atwood’s novel doe draw on real events and rules that have been applied to women, this should not come as that much of a surprise. After all haven’t you seen the photo of a bunch of old white guys deciding that maternity care is not essential for health? Haven’t you read about the anti-abortion bill that was signed by a white man surrounded by white men? Haven’t you heard of the Saudi Girls council with just men? The Russian loosening of spousal abuse laws? How about the women leaving Saudi Arabia because of the constraining laws? The various Texas bills and laws concerning abortion? The lawmaker who referred to women as a host for the baby? The fact that in many countries young girls can legally be married to older men?

So yeah, The Handmaid’s Tale is real, and this book really proves it.

Unlike Atwood’s fact based dystopia, Zakaria memoir showcases the erosion of rights and standing as a woman actually becomes a leader of the country. The trials and tribulations that the women endure might not be common to all at least on the face, but at the root? At the root, it is.

But the memoir isn’t just concerned with Pakistani politics, but also with the effect of international politics on the ordinary Pakistani citizen. (I for one wish I had read this prior to reading A Golden Age). It is non-linear, so it will put some people off, but if you give yourself over to the voice, it is like you are having a cup of tea with the author. -

The story of Aunt Amina and her husband Uncle Sohail is the primary focus of the book. However the shadow of the Pakistani India conflict and the continual Islamization of Pakistan forms the over riding feature of the story.

I like family sagas. I like the rich, descriptive detail found in such stories. The links within links and in an Asian family with its huge extended family the saga is always more complicated, richer in detail and somehow more intimate.

Amina is married to Sohail and after over a decade of marriage he decides to take a second wife. Taking a second wife is allowed in Islam but you do have to get the permission of the first wife. This was not done in this case and I think it is not done in a lot of cases. The wife tends to get shoved aside in placed of a newer and more glamourous entity. In this case the over riding cause was that Amina did not have children and for Sohail this was of primary importance. Egged on by his elder sister (in the absence of his mother Sohail's elder sister wielded clout that a Western woman could not even dream of!!!!), a new wife was found. Unfortunately for Sohail this wife too did not produce the required heir.

The story is told from the point of view of a ten year old girl, herself the niece of the said Amina. The family is a joint one and her mother is trying to balance the dictates of her own mother in law who asserts herself on even the smallest point to get her own way and try to "put one over" her independent daughter in law. The case in point of getting a driving licence and for five years having to be accompanied by her father in law whose instructions on how to drive, what to do and what not to do whilst driving despite the fact that he did not know himself to drive was a case in point.

Amina's story is set in the time frame of the family's migration from Bombay in India during the Partition. The historical detail was fascinating for me. How a country due to the dictates of first the British was just divided - entire families, communities being uprooted and said now you are Pakistani, now you are Indian. The administrative chaos that must have ensued. The documentation for each individual must have been a nightmare but survive all this they did and families like Amina's moved to Karachi and made a life there for themselves.

The new migrants were not all that welcome. They brought with them a different culture and a different way of life and were looked on as outsiders for decades. The partition of Pakistan, the division and declaration of Bangladesh as a separate country, and the Islamization of Pakistan with its strict Shariat law are all part of this story. The story of the different politicians of Pakistan and what part they played in what Pakistan is today is also detailed in the story. The rise and fall of most of the Presidents of Pakistan is a turbulent story in itself, full of violence and upheaval and military coups and families lived, survived and prospered within this framework.

I loved the writing of this story. I liked the detail. I liked the fact that I was reading something which actually happened and will continue to happen in Asian families upto date. -

I'd really rate this book a solid 2.5 stars if I could, but not 3. What is it about this nonlinear storytelling? I don't understand why the author jumps back and forth among the 1940's, 1960's, 1970's, and more current events. It's distracting and annoying. I also expected to learn more about an account of a woman living the life of first wife in a polygamous relationship. The book sort of did that and the word "history" is in the title. But the book is more about the history of Pakistan. Which is fine if I weren't expecting something else. Worse is that the family history ran parallel to national history. The two didn't complement each other or intersect at all. They could have just been two separate books. Not terribly creative at all.

-

The soiled country had to be sanctified again, and the ceremony took place on May 16, 1991. A new prime minister, clean and pure as only a man could be, had introduced a bill that would allow the country to expiate for the sin of electing a woman.

It’s so disappointing to be disappointed by Rafia Zakaria’s writing because I was expecting it to be, if not the best thing I had ever read, at least better than what it turned out to be. And what’s even more frustrating is that I think this book could have done much better as two books: one related to the politics, and the other about Zakaria’s aunt.

Of course, I’m guessing that there’s probably a good reason why Zakaria (and her editor, and publisher, and whoever else was involved in this endeavour) thought it was a good idea to juxtapose the two major threads of these two completely unrelated narratives into one, but it just didn’t work. Primarily because, except for a few singular exceptions where the two plotlines complemented each other, most of the book displayed a complete divergence in terms of the tone, theme, and/or events unfolding in each of their respective corners. If well handled, this had the potential to be brilliant. Unfortunately, it wasn’t.

Zakaria seems to have plotted it so that throughout the book the two stories, or rather, two non-fiction accounts, are being unspooled side by side. On the one hand, we have the story of Aunt Amina, the author’s phuppo, who had to suffer the indignity of her husband choosing to marry again because she couldn’t bear him any children. It is her position as the titular ‘upstairs wife’ that Zakaria uses as a vehicle to take a fascinating look at the way patriarchy, culture, and religion combine together to treat women less as a being with agency and feelings, and more as a child-bearing machine.

The purpose of a marriage was a child. The purpose of bearing children was to eventually bear a male child. The purpose of a male child was to be an heir.

The other half of the book details Pakistan’s history, stretching from partition up until the moment of Benazir Bhutto’s assassination in 2007, one of the many turning points in Pakistan’s tumultuous political history. In turns using a tone horrified or wry, Zakaria lays down the bare facts of the major events in the country’s history, which have been turbulent enough to make us pity every Pakistan Studies student out there. With regularly attempted coups, martial law implementation, hanged prime ministers, and assassinated leaders among the few scandalous things the past few decades can offer us, Pakistan has an overabundance of titillating political drama, enough to keep any non-fiction writer worth their salt in the business for a while.

Unfurled before a Parliament of men clad in pristine white tunics and vests tailored to hug rotund bellies, the Enforcement of Shariat Act declared itself the supreme law of Pakistan. The act next declared that all Muslim citizens were required to follow Shariat, and that the state, under auspices of the act, would insure that Shariat was taught in schools, practiced in law courts, and dominant in matters of state, economics, and exchange. Swooning with repentance, no one seemed to notice that the act neglected to say what Shariat was or which version of Shariat among the many existing schools and subschools of Islamic thought and countless splinter groups would determine these important questions.

It is clear enough, if you read the two parts as separate entities, that Zakaria can write really well. There is a visible ease in the flow of the writing, and a certain amount of command over the words she uses. Read enough books and it becomes easy to identify the confident writer versus the one who waffles over each and every word; Zakaria seems to fall into the former category, which might be the main reason why this book managed to not fall into the black void of books I hated with a passion. In parts where I wanted the book to just finish already so that I could get to better, more interesting novels, it was the writing that kept me reading instead of forcing me to slot this book into the ‘books I’ll probably never finish’ pile.

She disappointed, not because she was pretty or even ugly or interesting or boring or tall or short or intelligent looking or bearing on her forehead the telling mark of the simpleminded. She was a shock because she was so unremarkable, so lacking in anything special that as a result, she became an affront to the provocative idea we had constructed in her place. Uncle Sohail’s second wife was like the lady you might meet at a visit to the next-door neighbors’, or like the woman you could join with in accusing the tomato seller of being an extortionist, or like someone you might greet respectfully as the mother of some girl who was a friend of a friend. In her bland regularity she was an accusation as vexing and confusing as the betrayal she represented.

The problem, then, wasn’t the writing, but the content, which lacked any incentive to keep the reader reading. Now, since I’m not a very regular non-fiction reader, I’m going to go with the fairly basic assumption that non-fiction doesn’t follow the same pattern of introduction, rising action, climax, and ending that a normal novel follows. In which case, how exactly does nonfiction claim to retain the casual reader? I’m not talking about the people who have a vested interest in learning and retaining the information presented in these kinds of books, but rather the browser who picks these books up just for the sake of it.

This is clearly the kind of detailed discussion I need to have with my friends, but for reference’s sake, I’m just going to list here all the concerns I have with this form of writing, the most primary of those being the sharing of really, really personal information. While most autobiographical writing has the advantage of the person controlling exactly what is being said about them, I just can’t help but wonder how, in this particular case, the author’s aunt feels about having her dirty laundry aired so very publicly. While I’m all for a clear, honest look at the suffering women endure caused by the convoluted, brutal conditions placed by patriarchy, we really get into the nitty-gritty of Aunty Amina’s sorrow here, in a way which makes me both horrified and a little bit embarrassed for her.

One day a visiting older lady assessed my aunt’s dejection and rendered her verdict before us all: Aunt Amina owed her husband gratitude... The children of the new wife would brighten her life; she had no right to weep and make it out to be such a tragedy.

I also always wonder how the other people being named and shamed in biographical content feel about how they are being depicted. I mean, in this case it’s not a very hard stretch to guess that Zakaria’s aunt must have provided a significant amount of the details of the things that happened (especially since lots of things involved only her presence and those of people whose perspectives are never shown). But how do the other characters, such as Amina’s sister-in-law, who initially loves Amina but then becomes dismissive and condescending after her brother’s second marriage, feel about how they are shown? In this case, the sister-in-law (Aziza) is just one example of the multiple people whose depictions are sometimes flattering but sometimes not really, not at all, and I’m left wondering what are the lines which shouldn’t be crossed in such a method of storytelling, and how much of the author’s own opinions are allowed to colour the writing.

The jolly woman who brought gifts and lavished praise had vanished once the new bride had been installed in her brother’s home. The new Aunt Aziza expected complete submission from her youngest brother’s wife and daily devotion, which spanned from a morning phone call to ask after her health to a full meal cooked and sent to her home every Friday. On Sundays all the wives of her brothers were expected to pay homage to their matriarch, digest her evaluations of their lives, praise her children, and often even clean her house. No detail was too private: for years Aziza Apa had been inquiring every month, before all gathered, whether Aunt Amina was pregnant.

I’ll admit, though, that Zakaria doesn’t really try to insert herself into the narrative much. Most of what she shares has to do with her ancestor’s journey from India to Pakistan, leading up to her Aunt’s marriage, and then the disgraceful second marriage. Even though in some ways it helps give a veneer of impartiality to the overall account, I personally felt that the parts where the writing shone the best was where the author got personal about her own thoughts and feelings.

Mostly, this has to do with the fact that in the parts that she did get personal, she talked, in a frank and open manner, about how life has treated her differently because of her gender, which is a conversation I’m always willing to engage in. And because, instead of being didactic and insufferable, she made it part of the story she was telling, I found it even more interesting to read.

The window of the upstairs bedroom from which Amina first saw Sohail became mine. I shared the room with my brother, but the window was mine alone, as only one of us felt compelled to look outside. Not permitted to roam the streets like my brother, the window was my avenue to the world beyond our house.

Unfortunately, we don’t spend a lot of time with Zakaria herself, veering back into boring territory pretty much regularly. And while one could assume that the parts of me that grow impatient with non-fiction would have suffered more, the truth of the matter is that Aunt Amina’s portion of the tale also sometimes dragged. There’s only so many ways you can talk about the unfairness of a second wife before the chronicle starts to lag, and I found myself losing interest about halfway into the book. Maybe that’s a pretty heartless thing to say, but a large portion of my reading experience was spent wondering when the good parts of the writing were going to appear. And while they would appear briefly, they would also disappear as quickly as they had come.

Overall, then, I’d say it’s an okay read. Maybe a bit more interesting for the non-Pakistani reader, for whom Zakaria spends a lot of time explaining things that any Pakistani would already know about. Maybe some parts of it important for those who have no idea of the realities of trying to survive in Pakistan’s patriarchal society. But generally, I’d say only those who are truly interested should bother reading this.

And as a parting note, I’m going to share a quote here, which managed to so perfectly describe the complications that define the politics of living in Karachi that I actually highlighted it while reading. I’ve always been honest and transparent about liking authors who seem to truly understand Karachi, the city where I’ve lived my whole life. Because there are already so many stereotypes out there about Muslims and Pakistanis, these particular gifts of writing where I suddenly read something that makes me stop and think, ‘Yes, that is the essence of Karachi’ are particularly heart-warming. While Zakaria didn’t mould Karachi into a personality the way other authors have done, she definitely gets those few extra points for understanding the intricacies of its streets.

It was not enough to be born in Karachi to be from Karachi. It was not enough to live in Karachi to be from Karachi. It was also not enough to be born in Karachi and to live in Karachi to be from Karachi. To be from Karachi, you had to prove that your father, and preferably his father before him, had been born in Karachi and lived in Karachi, and therefore were from Karachi. If you were from Karachi by these markers, you could claim to be from Sindh, the province in which Karachi was located. If you could claim to be from Sindh, you could claim a lot more—a larger quota for government jobs, a larger quota for seats in government colleges, a larger quota on belonging and so a greater chance of making your life in Karachi as comfortable as possible.

***

ORIGINAL REVIEW:

What is it with all these cool Pakistani writers letting me down? Ugh.

Review to come. -

No star rating, because I did not get far enough. It skips around so frequently and from 1986 to 2007 to whatever era- and in placement to locale as well. No continuity. The history of Pakistan is set within the copy of her Aunt's story, her story, her childhood, dogma, and 1,000 other related context to polygamy or legal issues- but none of them connect to make a literate progression. Not for me to dig out the author's tale amongst 20 others.

-

A memoir of growing up in Karachi, The Upstairs Wife gives context to the life of women behind the walls of a middle class Muslim home in one of Pakistan's great cities, where men make the decisions and women accept the consequences. Aunt Amina is given in marriage by a contract negotiated by her male relatives who didn't think to inquire about the possibility of her spouse acquiring a second wife. When Amina tries to return in protest, she is sent back to the husband who divides his time religiously between the upstairs and downstairs wives.

It's hard for a westerner to comprehend the complete discounting is the value of women in contemporary Pakistan. Benazir Bhutto seemed like a harbinger of a new order for women. But she was fairly quickly cut down to size and ultimately assassinated, not the only woman to pay for stepping outside a woman's role in this book. Stoning is the penalty for adultery and a woman's word has only half the weight of a man's word in Shariat courts. Jealous husbands, with or without what a western court would accept as good evidence, have it easy.

The other side of women's life in Pakistan is the comfort of family, the clear knowledge of what is expected, and the rituals of daily life. Zakaria's accounts of everyday events like shopping, cooking, and gossip are rich in detail and beautiful. Wedding feasts, Ramzan women's gatherings under cover of prayer meetings, and even the ritual goat slaughter and sharing are well worth reading.

Zakaria's story ends differently that the average Pakistani's. She is a feminist who left and achieved a university degree and international stature. Fortunately, she allows women's stories to speak for themselves. The stories are powerful but left me wondering how Pakistan's women might emerge beyond traditional life to claim lives of their own. -

A Goodreads and Beacon Press Giveaway. Thank You!

The Upstairs Wife is a thought provoking and well written story of life in Pakistan. It is a memoir of Pakistan’s unsettled history and a family’s polygamist marriage. The women’s stories of their uncertain future were of particular interest. The story provides us with a little more understanding of life in a troubled part of the world as seen through the author’s eyes. Beautifully told. I highly recommend this book. -

I am not sure how I first discovered Rafia Zakaria, but I clearly remember the first time I read something by her. It was an article by her in 'The New Republic' called 'Sex and the Muslim Feminist'. It was a fascinating article and I loved it. I have wanted to read more by her since. I finally got around to reading her first book 'The Upstairs Wife : An Intimate History of Pakistan'.

'The Upstairs Wife' starts with the story of Rafia Zakaria's aunt, Aunt Amina. When Rafia was a child, one day Aunt Amina visits their home and stays there overnight and for the next few days. It is something unthinkable during that time, because married woman don't stay overnight in their parents' homes in Pakistan. Over the next few days, the story slowly emerges – that Aunt Amina's husband Uncle Sohail had decided marry again and get a second wife (which was allowed according to the law, but almost never happened) and he had come to ask her permission, but she had refused, and inspite of that, he had decided to go ahead. Aunt Amina had got upset and had gone to her parents' home. After the elders from both sides meet and discuss the situation, at some point Aunt Amina goes back to her husband's home, to share her house and her husband with a second wife. At this point Rafia Zakaria goes back in time and tells us the story of her grandmother when she was living in India in Bombay, before the partition. Then she narrates a third story about Pakistan as a newly independent country. Zakaria weaves these three story strands together – her aunt's story, her grandmother's story and Pakistan's story – and we get this beautiful book called 'The Upstairs Wife'.

'The Upstairs Wife' weaves personal story and historical narrative together into a fascinating book. I loved reading the personal stories and experiences of Zakaria's family members and the stories about Pakistan as a new country. I think the love story of her grandparents Said and Surrayya deserves a separate book. I knew about some of the events of Pakistan's history, but it was insightful to read it in detail in the book and understand the way it impacted Zakaria's family. Zakaria's packs in so many historical details into this 250-page book, that it is hard to believe how she managed to do that. The story that Zakaria tells is sometimes beautiful, sometimes moving, sometimes heartbreaking. There is one place where she describes how her grandfather goes to the government office to get something called the domicile certificate for his grandson. This certificate proves that one belongs to a particular place. To prove that one belongs to a particular place, it seems one has to prove that one's father belongs to that place too. And to prove that one's father belongs to that place, it seems that one has to prove that one's grandfather belongs to that place too. It was so absurd and almost Kafkaesque, that I laughed when I read that. And then it made me sad and angry. But this is not the situation just in Pakistan. Immigrants from time immemorial, in every country, have faced this question on where they are from and have been asked in increasingly absurd ways to prove that they belonged to a particular place. It is sad and heartbreaking. Zakaria's grandfather doesn't give up though and is unfazed by these bureaucratic mountainous obstacles. He pushes ahead with dogged determination, and we cheer for him, and he wins in the end, and we want to hug him and give him high-fives. I hated Uncle Sohail at the beginning of the book, but towards the end I felt that he was not as bad as it looked, and things were more complex than I imagined. I think that was one of the great things about Zakaria's writing – it was unsentimental, non-judgemental, and she followed the golden rule, 'Show, don't tell.'

I enjoyed reading 'The Upstairs Wife'. It is a fascinating look into Pakistani history of the last 70 years seen through the eyes of a few individuals. I am glad I read it.

Have you read 'The Upstairs Wife'? What do you think about it? -

First of all, thank you to Edelweiss (National Association of Independent Publishers Representatives) and Beacon Press for allowing me to read the e-book of this memoir before it was published. This really is a privilege.

It is September and I have read a lot of books so far this year. The vast majority have received three stars from me. As others have lamented on this site, the star system leaves a lot to be desired - which is why I write reviews. My rationale for why The Upstairs Wife receives three stars and a romance novel gets the "same" three stars really isn't at all similar. I struggle with this every time I rate a book.

This memoir would get five stars from me if I was rating it on new knowledge alone. I read to learn about new places and ideas. Zakaria gave me so much information about Pakistan, Karachi and Muslim culture and law. What she taught me helped me understand a little bit more about that part of the world. I am very grateful.

The reason that I give the book only three stars, is that I expected a more personal story. I wanted to know more about The Upstairs Wife and her husband and their families. I learned something about them, but I was looking for more. This may be a cultural bias that I don't even realize I have. It may be that Zakaria gave us all the personal information she felt necessary.

I recommend this book to people wanting to know more about now families function, especially with information about other cultures and other peoples' history woven through the family's tapestry. I wish Zakaria well. I hope her family's story is read by many. -

This is a somewhat odd book, a combination of a family memoir and an episodic history of Pakistan. It's engaging, but only in a superficial way. The historical anecdotes are rather sparse, and it's not possible to construct any clear or illuminating narrative about the recent history of Pakistan. The familial sections are a pleasure to read, though I did feel somewhat blindsided by the final revelation that the marriage at the heart of the narrative was seemingly a sham in the sense the husband was indifferent to the whole relationship. I also wish the author had given us more of a sense of her own perspective - though she witnesses all the events, we are left to wonder what conclusions she drew from Amina's experience.

-

This is good, but I feel that the “history” is too episodic, and the book too short, to give a full picture of Pakistan. I would have preferred a more thorough account of the family, with the historical events framed in such a way that how these events affected the people in the book. Overall, the book does a good job of portraying Amina’s pain when her husband takes a second wife and gives a glimpse into Sohail’s subsequent grief, but for the most part I finished the book knowing very little about anyone as a fully-developed person. It’s still a decent read, and it is interesting, but I was a bit disappointed in the narrative as a whole.

-

Not what the flap says it is, but still a fascinating read. To the shock and horror of the family of Rafia Zakaria, her aunt Amina finds out her husband wants to take a second wife after about a decade of marriage. Multiple marriages are permitted in Islam (a man can take up to four wives) but her aunt is very much against the idea. However, she has not borne any children, and her husband wants sons.

So the book begins. While the reader may think it is about Amina and the author's family, it's actually a story of Pakistan, much of it involving the roles women play and how they have shaped, changed and moved in the history of the country. It was extremely fascinating, especially once I figured out that the book is not just Amina's story, but Amina's marriage interwoven through the history of the family and their decision to live in Pakistan after the Partition.

That said, sometimes the content is a little confusing. There are sometimes huge time jumps (about 7 years towards the end) that made me wonder: Wait, what happened in Pakistan then, particularly in the years leading up to 9/11? Nothing about the assassination of Osama Bin Laden (although other killings and raids are discussed). Sometimes I was also left wanting to know more about particular figures, such as the wife and daughter of Muhammad Ali Jinnah (the founder of Pakistan) or even Sohail's second wife, especially considering how her story ends.

Overall, though, it's definitely an excellent read if you have any interest in Pakistan and/or women. Usually I hate it when books turn out to be different than what the flap says or what I expect, but I was pleased to see this book turned that on its head.

That said, it's not a history book and there are little to no references (there's no bibliography). So someone using this for research would probably be well served in picking up other sources and references to round out their work. -

Zakaria, a human rights lawyer who also writes a column for a Pakistani newspaper, has written an engaging history of Pakistan. The country's name means "Land of the Pure": It was created as a Muslim breakaway from India. Zakaria looks at the country's search for purity.

Unsurprisingly, purity means purity for women, not purity from corruption or violence. Pakistan was born in blood, and so was the separation of Bangladesh. I hadn't realized that one of the catalysts for the Bengali Muslims break from Pakistan was a terrible flood that killed many thousands of people, and the fact that Pakistanis in the rest of the country didn't understand the loss. They didn't even hear about it for three days.

Even after the bloody war in which Bangladesh, supported by Pakistan's archenemy, India, broke away, Pakistan still had many forms of discrimination, including discrimination against people who had migrated from India and their descendants.

Zakaria tells both the political history and the personal history of her family, focusing on her aunt whose husband married a second wife. When he did that, decades ago, polygamy was uncommon, and Aunt Amina suffered neighbors' scorn as well as pain inside her marriage. She lived in a partitioned home. Her husband spent alternate weeks with his two wives. Amina never accepted that division. She never was happy.

But at least Zakaria learned from her aunt's example how to avoid being trapped.

This book is a great way of learning about Pakistan. It takes the reader up to the present, where Afghan warriors have become a presence and militants encircle Karachi.

She says little about one subject that interests many Americans: Pakistan's nuclear weapons. But do read this book to learn how fragile Pakistan is and how the country became more and more opprssive to women. -

Her name is Rubiya saeed. She is 23 year old medical intern in Kashmir. After a long gruelling night shift she leaves the hospital only to be kidnapped. She is also the daughter of the interior minister of India.

Students, all female move out of the bounded, walls of the North Nazimabad College. These girls have been raised in an over protective environment yet they all are protesting together for their fellow student killed mercilessly by a bus right in front of the school.

It is still the Pakistani Dhakha. Provost makes sure that every single student living in the hostel of Dhakha University reaches home safely. A war by their own is looming just outside the door.

Amina, living a half-life as a half wife in a small house in Suburban Karachi. Benazir Bhutto, the powerful female prime minister who failed to change any anti women laws in Pakistan. These are all women with some times interesting and some times mundane lives.

The upstairs wife is a non-linear narration. It tells the story of many women and many lives all against the backdrop of a postcolonial Pakistan. Rafiya Zakaria moves between different stories. The book is an anthropological account. It is a political narration and a cultural commentary. It shows the other face of a society, which is deeply religious yet the cultural baggage of the past hangs on the daily lives.

It is a story of a world where women can be prime ministers, lawyers, teachers, doctors, and daughters of powerful men and yet remain powerless at the same time.

As a child of 80’s from Pakistan, I can relate to many chapters in the book. Rafia reclaims the history of pakistani women. The book is an ode to Karachi.

Rafia is a superb writer. The book is a definite recommendation. -

Rafia Zakaria's delicate deftness has resulted in a book that is the perfect and devastating blend of tender and brutal. The Upstairs Wife is, as its subtitle suggests, a wholesome narrative of Pakistan. Zakaria's work is a tapestry of histories of her family, of her grandparents, Said and Surayya, who migrated from Bombay, of the lives they built in Karachi, of her parents' lives, of her own childhood and, most importantly, of her Aunt Amina, whose husband, against her wishes, married another woman and was forced to live a half-married, sequestered into the upstairs portion of the house and entitled to only half of her husband's time and attention. Woven into this tapestry is everything from the bloody Partition in 1947, the early years of Pakistan, the transformation of Karachi over the decades several wars and military dictatorships and much, much violence.

What The Upstairs Wife does well is render transparent the selectivity of history - what it talks about most and focuses most on are topics not commonly found in our history as it is written, read, and understood today. Zakaria gives voice to the woman who have been silenced, both by society and, thus, by history, and lays bare the burdens they have borne in this country, the horrific violence and trauma they have been subjected to, and the victories - big and small - that they have won. -

The upstairs's wife's story is woven into the story of Pakistan's history since its partition in 1947. She is the shy, unimposing first wife who is replaced by a second wife and made to live on the second floor of the family home. The home is in Karachi, a city of more than 14 million people. The ethnic mix is described well showing what are the expectations, beliefs and privileges or restrictions imposed on each class. This is an interesting book and a good introduction to the history of Pakistan.

-

This book was interesting because I didn't really know much about Pakistan and how it came to be. I like that there were a lot of historical facts intermingled with the author's own story.

-

Moving story..socially, culturally and religiously eye-opening book

Great book if your goal is to learn the history of Pakistan and a little bit of India. However, I am a little sad for what the women in the country has to endure for political, cultural and religious reasons. -

This book does not pretend to be more or less than what it is...and that is what I like best about it. It is written by an author who belongs to the 'Muhajirs' of Karachi and I am glad to read something which offers their point of views, struggles, challenges and triumphs. I am ashamed to admit that the book mentions two incident (Thar and death of Bushra Zaidi) which I knew nothing about-I am definitely going to try and get my hands on more books about the people who migrated to Pakistan after 1940s.

-

The book would have earned 4 stars, were there less political biases towards the end.

Also, I felt the book ended too abruptly, just when you were getting personally involved the the author's own life. -

This is a brilliant and insightful book, interweaving the politics of Pakistan with the author’s family experience.

Central to this book is the author’s aunt, her Aunt Amina. The author’s love for her and dedication to her is omnipresent throughout. As Rafia states-

“I could never forget her. The shadow of her marriage, her exclusion, her accommodation of a life she had never expected had cast its imprint on my own life. The memory of her misery weighed on me; the questions about her choices plagued me. How real had they been? How helpless had she been?” Here is familial love at the core, a beautiful thing to behold.

In part the task of this book is to try make sure that the unseen is made visible, that all or almost all of the denials and coverups are transcended,that the downstairs and the upstairs realities are seen; that the realities of Pakistani women are seen; that the the multiple realities of Karachi are seen; that the immigrants experiences are seen; that the fragilities of political leadership are seen.

This book ultimately transcends time and place. I saw my relationship with my own aunt in the relationship of Rafia and Amina. I see the coverups and denials as described in this book as similar to the ones I experienced growing up in rural North Carolina.

I consider myself fortunate to have read this unforgettable book. -

I received this book through a Goodreads giveaway. The book appealed to me because I know little about Pakistan & wanted to learn more. First, this is not a feel good, happy ending book. But that doesn't mean you shouldn't read it. Second, while the book is interesting, the way it's subdivided is distracting & didn't appear to make any sense -- perhaps it was supposed to be an analogy to Pakistan itself? But that doesn't mean you shouldn't read it. Finally, the book does do a lot to dispel the idea that all Muslim women are accepting of the misogyny that they encounter.

Overall, the book is interesting and thought provoking. I just wish it had been laid out differently. -

I found this book very difficult to read and it left me wanting. Wanting more about the women in this book, described in a very superficial way. There was no depth, no richness to their characters or their lives and the book was flat. It was made even flatter by the concurrent history of Pakistan and Karachi that never seemed to touch the lives of the women or their families. I read this to the end waiting for something that would give this book a reason. Interesting on a very surface level only.

-

Zakaria, a journalist/lawyer/activist, weaves the history of her childhood/aunt/grandmother with that of Pakistan's. Super appreciative of the crash course in Pakistan history&politics since its founding in 1947 - highlighting Benazir Bhutto, the first female prime minister of a muslim nation. The narrative centers around her aunt's drama - her husband takes a second wife without her blessing. Everything is interesting and informative. This is the way to write a ... can't figure out how to classify it, which is delightful.

-

beautifully written book, narrating ordinary every day life of a migrant family in Karachi with a parallel political context of the times. Every time I read a book from Karachi, I am left amazed, it almost seems like a story from another world in so many ways and yet I can clearly relate to many many aspects of every day life. The author could have been biased to an extent about her perceptions on certain political parties or figures which put me off a bit and made me question the authenticity of other political contexts provided but overall this was a really good read