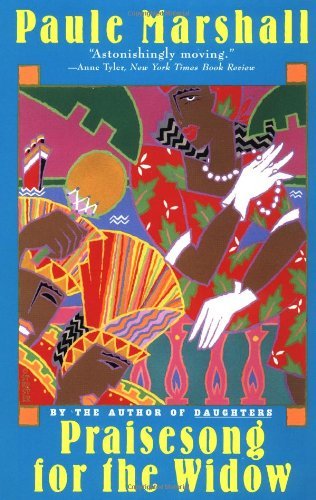

| Title | : | Praisesong for the Widow |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0452267110 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780452267114 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 256 |

| Publication | : | First published February 14, 1983 |

| Awards | : | American Book Award (1984) |

"Astonishingly moving."

--Anne Tyler, The New York Times Book Review

Praisesong for the Widow Reviews

-

I read this thirty years ago, but still recall it vividly. Excellent and underappreciated. Recommended.

Some years later... 2019 and I just read of Paule Marshall's death. I gave away my copy as a gift to an English Lit teacher who had first borrowed it and then was so impressed that she wanted to write an academic article with Marshall as the subject. Wonderful book, Marshall was a wonderful writer. -

Beautifully-written. The power and movement of this story took me by surprise. A black middle-class widow in her 60s, Avatara "Avey" Johnson---listens to her gut feelings while on a cruise with friends, and without consciously knowing what lies ahead, abandons her vacation schedule. Much of the bittersweet narrative consists of flashbacks about her life with her husband, Jay/Jerome, and their three daughters. What I loved most is that this turned out to be a healing story for Avey: about recognizing a rich history of culturally-specific spiritual resources, and being responsive to the needs of her soul.

-

This is another one of those books I allowed to languish on my to-read shelf for far too long. I found Paule Marshall's books thanks to Virginia Fowler, with whom my big brother and I both studied in college. If you haven't run into Fowler's work, well, run into it soon. She's one of the most fascinating people I've ever met, and she taught me to really learn and study. Ginny would make strong students shine, drag scholarship out of the laziest of students, or she would fail them--those were the three options in her class. I think I value my As from Dr. Fowler more than I value being accepted to present papers at conferences. Any idiot can convince a conference organizer that their paper is worth hearing--only someone who really works hard can get an A from Dr. Fowler. I should send her a fruit basket.

Praisesong is the story of the cultural epiphany of a widow. Our hero, Avatara "Avey" Johnson, is a widow and mother. She has a complicated relationship with her activist daughter and mourns the degradation of her marriage, which suffered under financial strains and then withered as money replaced love and passion. Avey goes on a cruise with some friends and ends up ditching them to forge a connection to her culture.

There are some sections of the book that could be tightened up a tiny bit, but the close of the novel (novella?) is masterful. Avatara reconnects to West Indian culture in a gorgeous ancestor ceremony. Very few writers can write ritual well, but Marshall pulls it off. She takes us to a scene most of us will never see, she treats it with reverence, but she also reveals the humanity of it all. I won't say more--just go read it. Read it read it read it. It's a great book. Read it now. It's small--read it twice. -

Excellent!

Lush beautiful prose that is incredibly taut. Not a word or idea is wasted in this beautiful novel.

Avey, short for Avatara, is a woman in her 70s on a cruise with two friends. ON day five of the cruise, her life comes crashing down on her and she decides she has to get off the boat and go home. She ends up in Grenada for a night, meets an old man on the beach the next day and goes off with on "the Excurison."

In between, she travels through her memories to grieve her dead husband, the pull of her Ibo ancestors in Gullah and the inevitable distance from that history she sees in her children.

I feel like I cam not doing the plot justice, but this was a truly lyrical novel driven by a strong and clear narrative.

I really liked it. -

This is a very complicated and layered text. Marshall is truly a literary genius. And to think, she worked with Langston Hughes?!?! It speaks a great deal to her talent and to her professional ancestry. I enjoyed the book, I loathed Avey Johnson (which speaks a great deal to the author's ability to develop such a realistic character), and found myself wishing there was more text beyond the last page. The only problem with this novel, and another guy in my class brought it up, you have to be somewhat of a scholar to read the text and actually understand what is going on. Thus, while Paule Marshall is brilliant, her intelligence is only appreciated by an esoteric few, while other black authors like Walker and Morrison, continue to amass critical and popular acclaim.

-

3.5/5

Here is yet another work I acquired when, after having spent so much time with the

500 Great Books by Women list and when came time for me to compensate for a lackluster showing of already committed to works at various book sales, this was one of the titles that rose to the surface of my brain. It wasn't until later, perhaps even during the course of reading this, that I realized the singular complexity of the piece, tackling as it does a broader spectrum of what is known as the "African diaspora" than what one usually sees in Black literature published in my neck of the woods. Simply put, a Black woman believes herself ready to sit back and enjoy the fruits of upper middle class living wrested through decades of struggle, sacrifice, and the death of her driven husband from a white and unforgiving world. However, such freedom has led to the slow but sure melting of her frostbitten cultural heritage, and from Gullah, to Grenada, to Ibo, she undergoes a pilgrimage not unlike the ones immortalized in the hagiographies of various female saints (not precluding the trials of endurance and humility such a journey implies) and comes out of it knowing she will never be the same again. It's wondrous when it works, but such a high level of interiorization combined with historical contextualization sometimes comes at the expense of a sustainable narrative and credibly distinct characters, and this narrative didn't quite pull off the balance required to commit to neither the fully banal nor the fully supernatural. Still, this was quite the unexpected treat of a read, as it will be for those willing to take on a read that would well benefit from its own set of footnotes/endnotes if the establishment ever woke up to the piece's potential.

There are an infinite number of ways of selling one's soul under capitalism. Some of the most popular involve the parent subsuming the child and using the promise of a "good education" to excuse any and all exigencies and abuses. Before I relocated to my current place of work, I thought I'd have to adapt my career to the rat race of college acceptances that masquerades as my hometown's chosen methods of childrearing and force every child I came into contact with into study mode whether they were looking for it or not. If you're lucky, and if you're lucky, and if you're lucky, you'll make it, but as the Avey Johnson, Avey short for Avatara, finds out during the course of this work, the price one pays for success might as well be the blood on the hands of Lady Macbeth: try as one might, it will not come out, leastwise not by any of the means by which one has so far been borne and bred for. What, then, will do so? Part of why I found myself so fond of this piece, especially during its middle section, was how it traced the seemingly inexplicable that came out in old age to the trials and tribulations of one's younger and middle years, and while I've never abandoned a cruise mid-ocean, dropping out of college is rather comparable. As I said earlier, how believable the rest of it is, with new characters popping up exactly when needed to forward the plot in the most painless way possible and Avey herself doing little save for passively experiencing flashback after flashback, rather hampers the full-throated effect: the message coming before the meaning, as it were. Still, it does make one curious about the descendants, and the mythos, and what happens when heritage is something worth celebrating, rather than yet another box to be checked on this year's tax return. Rare is the white person who is comfortable with all that in an anti-kyriarchal sense, but it's something worth pursuing, regardless of how one feels about this work here.

I'll probably end up returning to Marshall when I find myself in need of a women-authored work haling from the 1950s and nothing on my current TBR seems as inviting as

Brown Girl, Brownstones. However, I'm far more interested in any other works she might have that hearken to that breed of Black diaspora I caught glimpses of here and there in this work, heavily filtered as it was by normative, hand-holding, this-is-America-now-this-is-somebody-else stage that Anglo literature has a hard time extricating itself from. I've a good feeling James'

Black Leopard, Red Wolf will give me a certain something of what I want, and I have hope that an enterprising piece of nonfiction will come my way when the time is right. For now, I feel as if I still have to think about the rhythms of the past as inherited by the artificial escalator of the present, and how the key to the future is integrating the two and living life as a method of community, rather than as a means to a monetary end. There's a long way to go before that's ever resolved on a worldwide level, but with my country hellbent on pushing its populace to yet another brink during yet another year of pandemic, here's hoping I'll live long enough to witness when the citizens say, enough is enough. For what comes after will not be encompassed by the records of any supreme court, but what Marshall has to say here, and so I seek to read on accordingly in preparation for when the doings need to be done. -

i’m so glad i found my physical copy of this. the writing is beautiful and it makes up for the at times, confusion or slowness of the storyline. it’s really a beautiful story about how we are less separate from our ancestors than we believe and i love it for that

-

This is a book of fiction about a New York women who leaves her friends and her cruise behind at the first chance -- the Island of Grenada. This book has special interest for me not because I am a widow from New York but because I was in Grenada in 1983, the year the book was published. The main character is finding herself and in so doing meets an old man at Grand Anse Beach and ends up the next morning joining a group of out-islanders for an annual celebration. This book is to be read with a map of Grenada, a cool drink, and some Afro-Caribbean jazz playing. Enjoy.

-

This is the first book I've read by Marshall, and it moved up my list after hearing her described as a communist who moved in the same circles as Gwendolyn Brooks. That political association does feed into this narrative, which follows a grandmother, Avey Johnson, who embarks on a cruise to Grenada. The narrative splits its time between the present and various memories from Johnson's life. These memories, and especially Avey's relationship with her daughter, Marion, serve to reflect on the pre- and post-Civil Rights Era generations. Part of the reason Avey can go on this cruise is because she and her husband spent years focused entirely on work, rejecting their formal relationship to race politics, and choosing instead to chase the American dream. Time and time again, they are forced to recall their Blackness, and this anxiety, generated from Black middle-class aspirations, pulls the floor out from beneath them.

I heard that Marshall isn't always taught because her fiction is hard to categorize as African American or Caribbean Lit, and while that distinction requires its own essay, I did enjoy how this text explored the diaspora, allowing for questions of class to extend to questions of empire and nation. Furthermore, Marshall funnels intertextual mentions to various Black authors across the 20th century (Baldwin and Hughes, for two examples), to highlight and even interrogate literature's role in developing a notion of Black (but especially African *American*) middle-class consciousness. It's especially interesting to read this alongside Jamaica Kincaid's A Small Place, which is its own text that critiques tourism in the West Indies.

I might also recommend this book for fans of Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, a movie that explores the dynamic between African Americans and Black islanders. At one point, when an older man asks Avey what tribe she belongs to, she can only respond, “I’m a visitor, a tourist… I’m from the States. New York…” (167-68). She is at a loss for words, lacking the familiar forms of identification conditioned as a US citizen-in-the-making (I believe that could be an appropriate expression for post-Civil Rights era minorities, especially those in the still recent 80s). Ultimately, this work offers a less-highlighted way to question the nature of Black American identity. And beyond my special interest in class and citizenship, there is even more to be said for the text's depiction of time, memory, spirituality, womanhood, and other diasporic-inflected themes. -

I wish I had liked this book. It was given to me by someone I like and admire, but I just couldn't force myself to like it. There was some lovely moments in the plotting and writing, and I liked the brief glimpse it gives in Caribbean life and religious tradition, but overall, the book disappoints. I will credit it with being ambitious. It tries to tie (almost) contemporary African American life to both its slave and African pasts. But it isn't substantial enough to really succeed. Although it gives nice peek into the life of a mid-20th century, middle class black woman's life--and it is populated by older characters, which is a welcome change of pace--almost every character's motivations seem utterly opaque. People seems to fly off the handle at a moment's notice, but it was never clear to me why they were doing that. And yet so much depended on those bursts of temper. Still, we need more books told from the perspective of older characters--in this case, a woman in her early 60s--whose stories don't usually garner much attention in our current media/publishing landscape.

-

Surprisingly moving indeed! Speaking of surprises, don't be surprised when she craps her pants. I was surprised. How often does that happen? More surprising: that an old lady barfing and crapping all over herself on a tiny boat full of approving old people can be symbolic and moving.

Cuz it was. -

23 shower of scented dust

37 cool resinous smell of the pines

43 soap & asafetida

149 curdled milk & stale Johnson’s baby powder

150 staleness of flesh in slept-in clothes

166 seldom worn clothes & yeasty breath

190 blood

197 scented with mother’s cologne

215 slight mustiness of closed unused rooms

221 faint cool smell of limes on the air -

A wonderful story of cultural and personal self discovery. This book appears simple on the first take but is in fact quite profound. Avey Johnson may be a widow of senior citizen age, but her story is applicable to anyone who has ever tried to find out who they really are in the world.

-

This book was deceptively deep and meaningful. It took me a while to get into it but it had a profoundly inspiring effect. It reminded me that we all need to embrace our full humanity, even as we grow older and not stifle our natural "joie de vivre" in negativity and alienation.

-

I was forced to read this as part of my Women's Lit. class. It destroyed a piece of my soul.

-

A journey of self-discovery that contains the essential elements: longing, remembrance, heart, connection.

-

This novel was published in the 80s, and I can see its influence in many novels written afterwards. It’s not surprising that it’s considered a classic. It’s amazing and beautiful, bringing many far-flung strands together in the story of one woman.

The protagonist, Avey Johnson, is a wealthy older Black woman from New York, who goes on a cruise to the Caribbean with two good friends. In the middle of the cruise, she starts having dreams about her father’s great-aunt, Cuney, with whom she had spent childhood summers, on Tatem Island, on the South Carolina Tidewater. There, Avey remembered watching church elders circling around in a Ring Shout, moving without taking their feet from the floor. Cuney also used to take Avey down to Ibo Landing, the place where ships arrived carrying enslaved people, and there, Cuney told her stories about people escaping by walking on water, going back to Africa.

Avey hadn’t thought of her Aunt Cuney in years. When she grew up, she and her husband worked hard to build a secure, established life, raising three children, and when he died, Avey was pretty much set financially. So Avey can afford the luxury of this cruise. But after dreaming about Cuney, she no longer feels comfortable, and she decides to leave, upsetting her friends. She plans to get off at the next cruise stop, Grenada, and then take a plane back home to New York.

In Grenada, Avey finds herself immersed in a huge crowd at the wharf. They are all friendly and happy people, many of whom seem to know her, all speaking Patois (which she doesn’t know), and they’re getting on all sorts of small boats. She’s mystified and frustrated, but eventually she manages to get a cab. The taxi driver explains that these people are all going to their homeland, the small island of Carriacou, for a yearly excursion. He takes her to the fanciest hotel in town, and she makes a flight reservation for the next day. But she still feels restless and out-of-sorts, and she ends up taking a long, long walk down the beach. The heat gets to her in the middle of the day, and she takes refuge in a little grog shop, where an old man first tells her that they are closed. However, she feels compelled to talk to him, to tell him about her dreams, and he tells her that she must go with him on the excursion to Carriacou.

She agrees, although it means rescheduling her flight. And so she joins the crowds at the wharf, and gets on a small boat, headed for the island. With this, she is immersed in an intense, emotional experience.

The boat ride itself leaves her limp and weak, and on the island, she is cared for by women she doesn’t know – bathed and massaged - and has to surrender to this experience. I was really moved by the part in which her thighs, which have been encased in a girdle for years, begin to feel sensation again.

Then she attends the fete, a gathering in which the remnants of dozens of different African tribes are represented with their own songs and dances, mostly by the elderly. After this, the young people join in, and everyone dances together. All of it takes place in Patois, which she almost understands, and she finds herself caught up in a circular shuffle-step much like the ones she witnessed in her youth. Somehow, she knows exactly how to do this.

This experience changes Avey in a very deep way, and afterwards, she lives differently. In connecting with her powerful, loving, joyful ancestors – and with people who still celebrate this connection - she is freed. The writing is powerful, and yet very subtle, and completely immersive.

I loved the way this book brings forward the history that lives inside people. It populates the current day with spirits from the past, and mends some of the painful rifts between past and present.

Some quotes:

< He was one of those old people who give the impression of having undergone a lifetime trial by fire which they somehow managed to turn to their own good in the end; using the fire to burn away everything in them that could possibly decay, everything mortal. So that what remains finally are only their cast-iron hearts, the few muscles and bones tempered to the consistency of steel needed to move them about, the black skin annealed long ago by the sun’s blaze and thus impervious to all other fires; and hidden deep within, out of harm’s way, the indestructible will: old people who have the essentials to go on forever. >

< Avey Johnson stirred fitfully as the bewildering events of the last few days laid siege to her again, and immediately – her eyes still closed – she felt her elderly neighbors on the bench turn towards her. A quieting hand came to rest on her arm and they both began speaking to her in Patois – soothing, lilting words full of maternal solicitude. >

< They were almost halfway up the hill, nearing the crossroad, before her eyes adjusted enough for her to discover that the darkness contained its own light. >

< As the dances continued to unfold she discovered they followed a set pattern. First, from around the yard would come the lone voice – cracked, atonal, old, yet with the carrying power of a field holler or a call. Quickly, to bear it up, came the response: other voices and the keg drums. And the one or two or sometimes three old souls whose nation it was would sing their way into the circle and there dance to the extent of their strength. Saluting their nations. Summoning the Old Parents. Inviting them to join them in the circle. And invariably they came. A small land crab might suddenly scuttle past the feet of one of the dancers. A hard-back beetle would be seen zooming drunkenly (from all the Jack Iron imbibed earlier) around their heads. Sometimes it was nothing more than a moth, a fly, a mosquito. In whimsical disguise, they made their presence known. Kin, visible, metamorphosed and invisible, repeatedly circled the cleared space together, until the visible ones, grown tired finally, would go over to the lead drummer – the older man with the handkerchief around his head – and lightly touch the goatskin top of his drum and the music would instantly come to a halt. >

< “Cromanti. Is Cromanti people you see in the ring now.” Later: “Congo, oui. They had some of the prettiest dances…” Lebert Joseph continued to instruct her. >

< And then during one of the long intervals which followed each performance, he suddenly while standing beside her drew himself up on his good leg, raised his head, and his threadbare yet piercing voice offered up the opening verse and chorus of his nation’s song. >

< “He’s a Chamba, oui,” Milda spoke after some minutes. By then he had already been swept across to the circle by the tide of other voices joining his and by the drums, and could be seen forcing his stooped frame and uneven legs through the rigors of the dance. (“I’s a Chamba!” he had declared out of the blue, and in his pride his shoulders had almost come straight.) >

< The restraint and understatement in the dancing, which was not even really dancing, the deflected emotion in the voices were somehow right. It was the essence of something rather than the thing itself she was witnessing. Those present – the old ones – understood this. All that was left were a few names of what they called nations which they could no longer even pronounce properly, the fragments of a dozen or so songs, the shadowy forms of long-age dances and rum kegs for drums. >

< Yet for all the sudden unleashing of her body she was being careful to observe the old rule: Not once did the soles of her feet leave the ground. Even when the Big Drum reached its height in a tumult of voices, drums and the ringing iron, and her arms rose as though hailing the night, the darkness that is light, her feet held to the restrained glide-and-stamp, the rhythmic trudge, the Carriacou Tramp, the shuffle designed to stay the course of history. > -

When I started this book, I kicked myself for waiting 41 years to read it. But who was I at age 23? Naive. Optimistic. Unmarried. In Praisesong for the Widow, Avey Johnson is a full-fledged, complicated, middle-class Black woman. A 64-year-old woman, like me. This book is so beautifully written that I found myself reading it aloud at times, rereading passages, and closing the book with my finger bookmarking my place before continuing.

It is the 1970s. Avey, a widow of four years, and her two friends are on a cruise. Avey abandons her friends and the cruise in Grenada. She's distressed. A roiling discomfort gathers in her stomach, destabilizing her. Anxiety? Panic attacks? Avey wants to get to the bottom of this discomfort.

Through Avey, Paule Marshall draws a clear and emotionally compelling description of marriage, ambition, heartbreak, motherhood, and dashed dreams. We see the Johnsons' efforts as they strive and arrive, as they navigate the intricate nonsense of racism and Jim Crow. They make it, but in the process, they lose their attachment to Black cultural touchstones that fed and nurtured them in their early, struggling years.

Watching 64-year-old Avey find herself is something to behold. We see her come completely undone and watch as the women of Carriacou lovingly care for her. She is restored as she observes how the people honor their African roots. She begins to see connections to her experiences visiting Ibo Landing and her Gullah people in the South Carolina Lowcountry. As she flies home to New York, a plan of action for her next act takes shape. -

Avey (Avatara) Johnson is a Black woman in her 70’s from New York on a Caribbean cruise with her friends. Part way through the cruise, an overwhelming sense of unease hits her and she decides to get off at the next port and take a flight home. Her friends are shocked - this seems completely out of character for her, but Avey gets off in Granada and finds herself caught up in the annual excursion of out-islanders returning home to Carriacou. I loved the way Marshall unwinds the story using flashbacks so you get a sense of the life that Avey led that brought her to this moment. There were so many moments of connection to the choices that she made and the way that those choices and challenges set the course for her life. When she joins the excursion, you see more on the theme of connection, this time though to culture, identity, and sense of place. This was really a beautifully written book and I am looking forward to discussing with our book group.

-

I found the first part of this book intriguing but rather prosaic. Avey Johnson, the main character who suddenly abandons her long-awaited Caribbean cruise on a whim, struck me as so staid, so prim, and so proper. I couldn't identify much with her at all. But then the second section, which flashes back to all the events in Avey's life that have made her so timid and so conservative, brought her to life for me. What middle-aged woman hasn't come to the realization that somewhere along the way, she took a wrong turn and has become something less than she might have been? And after she comes to this realization, there is nothing for her to do but search for a new path. I ended up loving this book, and I'm very glad to hear that it's about to be reprinted this year by McSweeney's. Maybe you'll love it, too!

-

i can see why people call this book life-altering; it's a gorgeous, unabashedly heavy-handed read

-

4.5 review forthcoming

-

Loved it! Great for bookclubs. This book is rich in symbolism and meaning. The plot follows Avey Johnson, who, by unexpectedly leaving a cruise ship, rediscovers who she was, who she is and who she will be. Don’t do a surface reading of this one, every word, name and casual reference has a meaning that plays a part in Avey’s rebirth and finding her own Praisesong. -

A woman on a sort of pilgrimage to rediscover her identity. What I loved the most about the book were the authentic, almost spiritual symbols of being reborn and the way that Marshall represented transition and rediscovering as something not so pleasant but necessary.

-

I picked this up randomly from my library to read for Caribbean Heritage month. It is written by a Barbadian female author who moved to New York. In this novel we follow the story of a widow, Avery Johnson. It is a beautifully written story about losing yourself and your identity. This is written through the lens of race and the struggle for economic freedom. And its impact on a marriage.

Despite the beauty of the writing, the spiritual aspect didn’t work for me. The connection it makes with music, dance with African past is great. It just doesn’t for me. -

Read this for my Comparative American Literature class and I finished it in about three days. A powerful insight into the fear of exposing our true selves, Marshall's masterpiece is a true testament to the beauty of self-acknowledgement and trusting in our roots to help us decipher the superficial from the real. You could practically see the built-up, defensive layers of Avey Johnson's exterior peel away as the chapters progressed, but like all of us living in a society where our inner selves are taught to give way to outward impressions, Avey's transformation was slow, hesitant, filled with anxiety and discomfort. She is constantly depicted trying to find a balance between embracing her inner, more natural being and existing in the world of material things she and her deceased husband Jerome worked so hard to achieve, a far-from-easy task to accomplish. But no matter how much money in her pocketbook, no matter how large her array of sunhats sit atop her head, and no matter how many pieces of precious china she owns, memories of the true life she once had with her nature-loving great aunt lure her out of her life of frivolity and back into one of humility and self-appreciation.

-

Paule Marshall has a gift for using her flawed, but thoughtful characters explore relationship of their lives to the Black Diaspora without falling victim to abstraction. In this book a Harlem widow's mid-life crisis drives her from the routine and defined events of a vacation cruise in the Caribbean and towards the fragmentary and reconstructed rituals of Grenada and meditation on the unifying (if often frayed) threads of the Black Atlantic.

The book proposes a Black unity built on acknowledgement of its diversity without losing sight of the lived experience of a once-enslaved and still colonized people with the pervasiveness of what bell hooks would call the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

Sometimes Marshall's florid prose can seem old-fashioned, but it works to evoke her well-drawn characters in their particular settings, as community and place is as much a concern in her work as the individual (if not more so). -

An elderly African-American woman surprises her friends by leaving a Caribbean cruise before it's half over. She stays over on an island and participates in Voodoo dances. She doesn't know it yet, but she's responding to a pull from the past to come around full circle and complete things. In Praisesong for the Widow, Marshall wrote yet another book that hearkens African-Americans back to their robbed roots, but she does a better job of it than any I have read yet. Her descriptions of both the inner landscape and outer landscape, but especially the outer, are detailed and exquisite. I recommend the book for any race or gender.