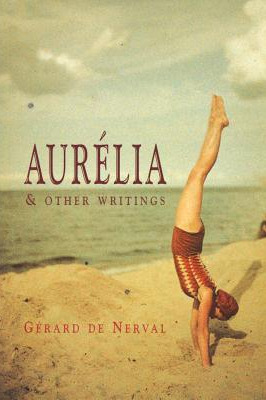

| Title | : | Aurélia and Other Writings |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 187897209X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781878972095 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 240 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1855 |

Aurélia and Other Writings Reviews

-

Every man is a reflection of the world…

The macrocosm, or greater world, was constructed by cabbalistic arts; the microcosm, or smaller world, is its image reflected in every heart.

Gérard de Nerval descends into his madness to find there Aurélia like Orpheus descends into Tartarus to find Eurydice. And the insanity becomes Gérard de Nerval’s underworld…I entered a huge hall where many persons were assembled. I recognized familiar faces everywhere. The features of relatives whose deaths I had mourned were reproduced in the faces of other ancestors who, dressed in more ancient garb, greeted me with the same fatherly warmth.

He’s journeying through his visions, he gets lost, he is terrified and awed…Then the monsters changed shape and, shedding their original skins, reared up more formidably on their huge hind legs and trampled the branches and the grasses with the enormous bulk of their bodies; and in this chaos of nature, they engaged in battles in which I also took part, for my body was as strange as theirs. All of a sudden a wondrous harmony echoed through our solitudes, and it seemed as if all the shrieks and roars and hissings of these elemental creatures were now joining in this divine chorus.

It is as hard to get out of madness as to get out of hell – just a single look back and the madness will reclaim you forever.

Suicide is a one way to say ‘Stop time, thou art so beautiful!’ -

Aurelia is a non-fictional account of Nerval's "descent into hell", perhaps precipitated by the death of an actress he was obsessed/in love with. During this descent he is beseiged with visions, both waking and sleeping, of universal love and unity and universal desolation. He is also beseiged by his own Catholic guilt for seriously dabbling in the occult for the purposes of figuring out these very visions. These conflicts entangled him in a significant psychic bind and landed him in an asylum, from which this document seems to've been written.

It begins with the famous dictum - "Our dreams are a second life," and continues from there to elaborate in great detail the substance of this second life, giving much greater credence to this second life than waking life. Through his trials and his meetings and "conversations" (more like direct mind-to-mind transmissions) with deceased friends and relatives and purely spiritual beings Nerval is convinced of the immortality of the soul, and this assurance of immortality is what saves him from total despairing madness. And so Aurelia ends on a positive note, though Nerval was not to survive long after the writing of it, hanging himself from a window grating in 1855. Poor Nerval, what a troubled and beautiful soul. Thank you for descending to Hell for all of us!

There are other stories, poems, and documents in this fantastic collection that I'm not reviewing, all of which are great or at least well worth reading (esp. the short sonnet sequence, The Chimeras, translated by Robert Duncan), but none have the raw immediacy (yet still classical French structure and control) of Aurelia -

As recommended by Rene Daumal, various Surrealists, and others. The title story is actually less fully dream-like than expected, but actually more a personal account of ones own descent into and intermittent recovery from insanity. In that sense, it does fit in well with various Surrealist's acounts of their own periods of delusion (Unica Zurn's

The Man of Jasmine and Leonora Carrington's

Down Below are key examples of this genre), while looking ahead to some of the oneiric accounts in fictions of the mid-century (Anna Kavan's 1948

Sleep Has His House or Doris Lessing's somehow more dated 1970s

Briefing for a Descent Into Hell). All of which company should suggest that I'd love this, but I didn't find myself totally enthralled by its largely diaristic realism. As a truthful record of its times, it is good, but for that, we have the other, sometimes even better stories, and essays here full of pastoral detail and historical sense of place. Even Nerval's interests tend to endear me to him, as he seems to wander about Paris and its environs in a proto-derive or flaneur fashion, dwells upon the losses of urban development, and obsesses about Isis and the customs surrounding her in antiquity.

My concurrent reading of

The Second Sex tends to color my readings of much else around it through it's sheer force and monolithic density (as it will for a while, give its near-endless 800 dense pages. In fact, de Beauvoir cites Nerval as belonging to the Bretonian tradition of gloryiging Women as the gateway natural wonder and inspiration, as one of the failed literary approaches to women, falling quite short of any authentic relationship. I'd say that Nerval actually fares a little better: his Aurelia may serve as guide to his dreamworld, but in an account of his own mounting madness, which rather turns the tables on Breton's exalting of Nadja, for instance. He's even acutely aware of the inherently problematic tendency to fall in love not with actual people but with his own images thereof. It's clear, even amidst his more rhapsodic passages, that this is his loss and he knowns it, not any failing of the women who move through his life and depart on to their own. So while Nerval may in some way illustrate the type of literary representation as de Beauvoir suggest, I was pleasantly surprised by the self-awareness by which he makes it rather more useful and interesting. -

I strongly caution anyone who treasures the precious little time they have on this beautiful, big, blue planet not to squander it reading the work of Gerard Labrunie (inspired to use the name Nerval in homage to the estate of a wealthy ancestor). If, in the most unlikely of events, you happen to be captured by some twisted gang of malcontents and forced to read the work of Nerval under torture, do your family proud and deny this ridiculous request until they’re forced to kill you. This sounds like a drastic measure, but maybe one of these two scenarios will help you summon your inner strength:

1) Consider the wise words of Dumbledore at the end of ‘Goblet of Fire’ when he wisely states “Remember, if the time should come when you have to make a choice between what is right and what is easy, remember what happened to [Cedric Diggory:]”. That’s got to hit home with just about everybody.

2) Recall the inherent heroism from Dad’s Nam stories; not the ones about catching the clap while on R&R in Bangkok or tossing bricks of dope on a bonfire. I mean the stories in which he’d pull off his hefty radio equipment after a firefight only to realize the thing had absorbed a few bullets which would have crippled him if that cumbersome crap hadn’t been present; the damn thing actually managed to serve a purpose other than help him understand how much it absolutely sucks to drag about 50 additional pounds of equipment around in a fucking jungle while getting shot at! Sure, they couldn’t call in that critical airstrike to turn the tide of the battle (probably in NVA favor, seeing as it probably would have resulted in decimating his peeps due to friendly-fire when some myopic bombardier tried executing a strike with surgical precision on battling forces under a canopy of foliage) but they bravely fought on and eventually won they day. Nevermind the compelling sidenote that after botching the re-wiring of this primitive telecommunications device, his squad discovered they were somehow able to place calls to 976-JUGS, sending the platoon into a downward spiral of lethargy and preposterous beat-off sessions previously unknown to the annals of Asian history.

Think about those kinds of sacrifices; Cedric losing his life to unknowingly help galvanize the resolve of the wizarding community to purge the blight of Voldemort’s resurrection and our going toe-to-toe with Viet Nam, which I can only assume thwarted the menacing spread of communism that would have made “1984” a certifiable reality. Anyway, whatever the reason, I strongly recommend staying clear of Nerval, especially this edition of Aurelia & Other Writings.

It comes as no surprise to me that this edition was published by Exact Change. If I’ve learned one thing over the past couple of years, it’s that the cretins selecting works at Exact Change might possibly be the most dunderheaded morons currently working in concert. They claim to specialize in ‘bizarre’ and ‘decadent’ works which are vastly ‘under-appreciated’ and ‘esoteric’, mistakenly believing that the rest of the world is ignoring these writings for a reason other than that they suck and are usually preposterously asinine. It also seems like they select their authors more on the grounds of ridiculous shit they gained notoriety for, rather than any actual talent for telling a decent story, highlighted by their tendency to preface each weak edition with a cute little narrative on just how uncouth the author was instead of mentioning anything which might have something to do with the actual book or any justification for publishing it, other than to perpetuate the fallacy that because some well-heeled cretin acting like a goddam nimrod has something to say there might be something of worth buried amidst the ramblings. Come to think of it, I should probably be working at Exact Change myself, since I apparently can’t review a book without digressing into god knows what, kind of like this review…

Anyhow, let this serve as a notice to any aspiring authors out there struggling to get published, you’ve probably got a good shot at getting an offer from Exact Change if you’re willing to make a few minor compromises, including (but not limited to): 1) participating in sexual extravagances, anything from orgies, to incest, to incestuous orgies, 2) being committed to an asylum or tragically succumbing to some form of madness, 3) evidencing your deteriorating mental state by doing imbecilic shit like walking a lobster on a leash, unearthing corpses and toppling headstones, or diddling yourself in public, 4) killing yourself (this helps reduce the time spent uselessly quibbling with Exact Change regarding royalty checks, and besides, you’re certainly not doing it for the money, right? you’re all about artistic integrity). Such appear to be demanding criteria which Exact Change sets for the scribes of truly inspiring and timeless literature.

Gerard Nerval somehow managed to squeeze a little writing into his hectic schedule of naked poetry readings and eating ice cream from a skull while on leave from psychiatric care. It’s unfortunate that he had this idle time, as eventually someone was going to come along and mistake his eccentricity as a sure sign that Nerval had something profound to say. His magnum opus, ‘Aurelia’, begins this collection of catshit, and it didn’t take more than a few pages for me to realize that if this is accepted as the guy’s best work, I was probably going to end up throwing this filth in Lake Tahoe before my four-day vacation was over. In consideration for the other nekkid freaks at the clothing-optional beach where we decided to catch a few rays, I realized it would be a travesty to befoul the lake in this manner. On the other hand, struggling through Nerval’s inanity didn’t help to make my manhood look any more impressive on this exhibitionistic stretch of shoreline; if anything, it seemed to have to opposite effect, so I abandoned any attempt to finish the book for the time being and admired the scenery while contemplating how best to tan nude without getting a sunburn on my crusty, old ballsac.

About the only way I can sum up my feelings for ‘Aurelia’ is to classify it as the male counterpart to The Bell Jar, an agonizing look at abject stupidity and self-perpetuated helplessness which caused me to beg for the author to just…fucking…end…it…already; their story, their life, whichever they can summon up the grit to accomplish first. The story is pretty simple; a turgid tale of unrequited and senseless infatuation for a stage-actress (Aurelia) on behalf of a maladjusted loser (Nerval). Perhaps what I found most distressing was that I just couldn’t give a rat’s ass for the dilemma the narrator is entrenched in; I’d like to think that the allure of the whole ‘love-in-vain’ genre is that you need to come to sympathize to some degree with the embattled admirer, or to at least understand the basis for the undying love which they are professing. 'Aurelia' doesn’t inspire anything of the sort. Worse yet, Aurelia has the nerve to get ill and die almost immediately, and from that point on (page 4) the story crawls along with the narrator taking every opportunity to exclaim ‘woe is me’ while scribbling a bunch of horseshit about how he’d been done wrong by fate while succumbing to the dread malady of insanity. Every sentence drags on indefinitely, convoluted with meandering nothingness concerning his ‘eerie’ dream sequences and choc full of nonsensical solipsistic ballyhoo and pagan symbolism, believe it or not, it may even be worse than what you’re reading right now, if you can possibly fathom that.

The rest of the book isn’t much better. The second story, ‘Sylvie’ is (not surprisingly) almost the very same story as ‘Aurelia’. In this variant of the story, Nerval is a childhood friend/lover of Sylvie and manages to squander any chance of having a life with her through his own dumbass nature. A quote from ‘Aurelia’ actually sums up this story rather well: “It is too presumptuous to pretend that my state of mid was brought about only by a memory of love. Let us say rather that I dressed up with this idea the keenest remorse at a life spent in foolish dissipation, a life in which evil had often triumphed, and whose errors I did not recognize until I felt the blows of misfortune.”. I think Nerval’s own words show why he’s such a crappy lover, and hopefully illustrate why I couldn’t give a damn about his problems, which stem from his wanton indulgences only for him to retrospectively shed tears in self-pity.

The second half of the book manages to decrease in quality. This travesty begins with ‘Octavie’, in which Nerval graciously shows us examples of the ‘awesome’ and soul-stirring love letters he often brags about creating, which only brought to mind the typically pathetic “if-I-can’t-have-you-I-will-open-a-vein” rambling you expect to find scrawled in the journal of a recent high school suicide. In ‘Isis’, the reader is mesmerized by Nerval’s trip to Herculaneum; allowing his pagan and occult bullshit to flourish. A complete waste of paper follows with ‘The Chimeras’, a collection of poems, in both English and French, presumably just to prove they rhymed in the native tongue, which might be their only

saving grace. In ‘Pandora’, our man Nerval once again makes an ass out of himself, and the book finally concludes with ‘Walks and Memories’, which I actually found to be the pick of the litter and the only story to make me crack a smile. Of course, it might not be coincidental that I also realized the book was drawing to a close at this point. -

I thoroughly enjoyed most of this collection-- particularly Aurélia and Sylvie. Nerval is truly a Romantic; he expresses an often childlike sensitivity to life, a purity and naiveté of yearning, which is something I really appreciated: the absence of vanity in his writing; the ring of truth. He is always inebriated with wistful longing, and it's easy to get carried away with him.

There is a strong melancholic undercurrent to his observations on internal life, his romanticizations, and the external world. The obscure confusion, the pathos, and the spiritual hope that permeate these writings is very lucid and very pungent--I see why Breton considers Nerval's writings the measuring stick for the surreal; there is truly something both lucid and dreamlike about Nerval's writings. The dreamy pungency is what I most appreciated--and despite the obscurity and dreaminess of Nerval's spiritual experiences, there is something intimately human about these writings; and when it's all finished with, a kind of wilted sadness. -

Aurelia so enthralled me the first time I read it, I immediately went back to it and read it again. I had to make sure I had not imagined reading it. There are ideas about dreams and insanity in this book that I have been exploring and attempting to digest in my own writing for years. At once it seemed both familiar and strange. This is a major wellspring for some later surrealist writings, namely Breton’s Nadja and Aragon’s Paris Peasant. Also, there is the translation of Sylvie in the Exact Change edition, which I could have done without parts of, but there is a very evocative scene when the narrator and Sylvie dress-up and play make-believe in a peasant’s wedding costume. Romantic, surreal, pastoral… wondrous.

-

As close as you can get to watching a person go insane, which means it's a wince-fest. Some amazing prose, like for instance the first paragraph. Last pages of this autobiographical novel were found in Nerval's pocket as he was dangling from the wooden beam he hanged himself from. Those surrealists...

-

An "almost pathological sense that reality is not stable," says my boy Warwick, and do I love that stuff? Yes I do.

-

The gorgeously bewildering Aurélia seems to provoke the most commentary, but it was the exquisite Sylvie that really knocked me out (as apparently it did Proust, who cited it as one of his major influences; later Joseph Cornell was similarly bewitched). Umberto Eco

describes it as "the dream of a dream," and that's a better summation of what to expect with this collection than anything I could possibly hope to come up with myself. -

The ultimate poet's poet, Nerval merges his dream world with the world we all share in these prose pieces, bringing about a kind of romantic apocalypse. Gorgeous and harrowing at the same time, the delicate pubescent longing of Sylvie becomes the cosmic eschatological last one standing narrative of Aurelia. Way out there. Not for everybody, though. Some might find his romanticism a bit much. Not me. It is just right. Blinding.

-

I wish everyone would read this book.

-

Written as a novella but pure poetry.

-

"What is madness...to go on platonically loving a woman who will never love you."

—Gérard de Nerval, Aurélia (1855) -

Having repeatedly come across Nerval in The Open Work and other writings by Umberto Eco—at a time when I was very much under the influence of the Italian—I was really pleased to find this handsome Damon & Naomi–published collection assigned in a seminar on fantastic literature in, I believe, 1997, and I offered to present on and write about it immediately. But it all seems like a dream now, and I can't remember much about the book, and I'm not sure what I would think of it now. I do remember that Nerval was known to take a lobster for a walk in a park, employing a blue—it must have been a blue—ribbon as a lead.

-

The author seems surprisingly modern.

-

Hadji tells me Nerval brought his own human skull to dinner parties to drink wine out of and that Proust loved him for his ability to narrate perfectly from the space between wakefulness and sleep. As far as I could tell, the protagonist of the main story broke up with his girlfriend, lost his mind, and traveled back to the genesis of time to re-live the history of the world, including witnessing rival Elohim battling on mountaintops, dinosaur-like beasts plodding across the landscape and passing through doors that open into hallways that open into doors that open into other hallways. I propose this genealogy: Nerval-Breton-Jodorowsky-Legend of Zelda and say, with respect to H and Andy, that I don't think the surrealists are for me. As George Franju put it, I don't like my dreams dreamed for me, at least not this winter. I'm fleeing to Stendhal.

-

Aurelia possesses the insanity of Artaud with the quasi-lucidity of Schreber, the literary prowess of Lautreamont, but with a Romantic/sentimentalist spirit that ends up being an inverse to Maldoror.

Becoming more and more convinced that "authentic" surrealist literature requires psychosis or something along those lines to create. Breton so desperately wishes he could have written like de Nerval, Lautreamont, or Artaud. But instead he will have to wallow in his pomposity and mediocrity while going on homophobic rants or whatever. -

The other major influence on the Surrealists, as well as on Proust and Joseph Cornell, Nerval manages to record the fantastic dreams and hallucinations that accompany his descent into madness. Before and after his madness he paints vivid scenes of childhood love, Parisian neighborhoods, and occult rituals.

-

more people should read this. dream, memory, insanity, love -

What's more tedious than random pomo ramblings? Occultist romantic outpourings

-

Worth it for Aurélia, which describes the author's hallucinatory descent into madness and was influential to the surrealists and other writers like René Daumal and Antonin Artaud, but the other texts are not worth your time.

-

چقدر زیبا حس گناه رو در کنار تک تک موضوعاتش به تصویر کشیده بود.

ترجمه این کتاب معرکه ست . -

I was tricked into buying a collection of Nevral's writing by Cocteau Twins - supposedly they named songs on their amazing album "Treasure" after some of Nevral's characters. I've only got through half of Aurelia and I don't know if I ever get down to read some other things.

"Aurelia" is mysticism and romanticism, understood as wrongly as possible - incoherent ramblings about myths from various cultures mixed together without a shadow of a doubt, half-witted ideas about paradise and immortality paraded like revelations, a character who loves a dead woman so tragicly, that the best he could to describe her or his feelings for her is to write "she" with a capital letter and in italics. Wow.

And about those dream sequences. Dear Gerard. You don't just write something like "and then I saw a thousand faces in a thousand rivers" or "some strange ugly beast rushed past me" to create a mystical, or dream-like, or spooky emotion. Nor do you constantly tell, that everything described in the story is utterly insane. Unfortunately it takes a little bit more of imagination to create books that are akin to dreams. -

During my sleep I had a marvelous vision. It seemed to me that the Goddess appeared to me, saying: "I am the same as Mary, the same as your mother, the same being also whom you have always loved under every form. At each of your ordeals I have dropped one of the masks with which I hide my features and soon you shall see as I really am." (pg. 52)

I found Aurélia and Isis to be the most interesting works in this collection. Nerval certainly exposed his soul to the reader. I can understand how he inspired other writers. -

i waffle between 3.5 and 4 stars for this.

the title section should be read last, in my estimation.

gerard de nerval writes with seething honesty. echoes of cervantes. lots of strange orientalism.

somehow i am always surprised that suicides often seem to reach a point of despair wherein they cannot read. it makes me wonder. -

one day when i want something esoterically insane and soft and fluffy to coast along... why did I get this book? why is it still on this list? what a pretty picture on the cover!

-

An inelegant, often clunky writing style dampens my appreciation for this otherwise excellent collection of works by Gerard de Nerval.

-

Disons que le romantisme/naturalisme n'est vraiment mais alors vraiment pas ma tasse de thé !!!