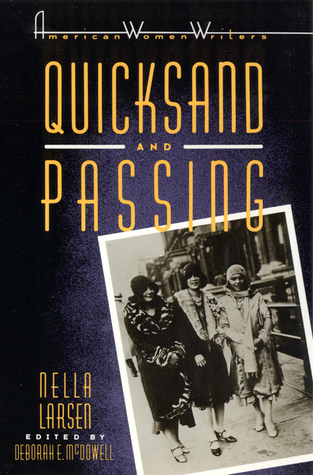

| Title | : | Quicksand and Passing |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0813511704 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780813511702 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 246 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1928 |

"Discovering Nella Larsen is like finding lost money with no name on it. One can enjoy it with delight and share it without guilt." --Maya Angelou

"A hugely influential and insighful writer." --The New York Times

"Larsen's heroines are complex, restless, figures, whose hungers and frustrations will haunt every sensitive reader. Quicksand and Passing are slender novels with huge themes." -- Sarah Waters

"A tantalizing mix of moral fable and sensuous colorful narrative, exploring female sexuality and racial solidarity."-Women's Studies International Forum

Nella Larsen's novels Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929) document the historical realities of Harlem in the 1920s and shed a bright light on the social world of the black bourgeoisie. The novels' greatest appeal and achievement, however, is not sociological, but psychological. As noted in the editor's comprehensive introduction, Larsen takes the theme of psychic dualism, so popular in Harlem Renaissance fiction, to a higher and more complex level, displaying a sophisticated understanding and penetrating analysis of black female psychology.

Quicksand and Passing Reviews

-

Quicksand

Helga Crane is a biracial young woman in the 1920s. Though she has some financial help along her way, she needs to work. All options open to her become successively disappointing, and depressing after her initial enthusiasm: a teacher in a school that models Anglo-Saxon values; employment in Chicago with a wealthy woman who introduces her to New York and friendship with another wealthy woman who disdains romantic biracial relationships; two years in Copenhagen being pampered and displayed by her mother’s sister; back to Harlem where she feels both more comfortable and uncomfortable; then to the South for the arguably abrupt denouement. Three men, only one of whom she loves, are unsuitable for marriage for various reasons; a fourth comes into her life at a vulnerable period. The short novel is psychologically astute and extremely well-written, especially for a first work.

3 stars (October 17)

Passing

Now that I know the ending, I should reread Passing. It certainly deserves to be. The close third-person POV is Irene’s and, once I got to the final section, it dawned on me how close of a perspective it is and how important it is to remember that when thinking of Clare, Irene’s biracial friend from childhood who’s ‘passing’ as white. Irene is as light-skinned as Clare and is married to a darker-skinned black man who’s a doctor; they have two young sons. (Skin color is important to the story and is described in various ways.) Irene has an extreme want/need/desire for security, which determines all her actions, but both women are constrained by lack of choices in not only a racialized world but a man’s world. This masterpiece of less than a hundred pages deserves to stand with other works I was reminded of while reading, works we consider genius:

The Great Gatsby;

The Good Soldier;

Mrs. Dalloway.

5 stars (October 23)

*

I told myself I didn’t need to reread Passing right away, but I had no say-so in the matter. I couldn’t move on until I did and I reread it last night. I still haven’t moved on: To explain any further would be to discuss spoilers, so I’ll leave it at that. (October 24) -

To lose oneself in the mire of identity crisis, discontented with life, love, and career. To seek true meaning and purpose, only to find that it eludes you:

Somewhere, within her, in a deep recess, crouched discontent. She began to lose confidence in the fullness of her life, the glow began to fade from her conception of it. As the days multiplied, her need of something, something vaguely familiar, but which she could not put a name to and hold for definite examination, became almost intolerable.

Oh, Helga. I lived with her, observed with her, got mad at her, empathized and sympathized with her, and was unhappy with how things ended for her, until I realized that I only have to look around me in suburban America, to look around me at life, and I will most likely see similar endings.

Ever read a book and imagine the words coming out of the mouths of people on a movie screen? I read these two books wondering why their movies were never produced (or were they?). To think that Nella Larsen stopped writing and went into a career as a nurse, is saddening, for I love the ebb and flow of her prose, and I was entranced by the storytelling here. I only wish there were more books of hers to read.

Quicksand was my favorite of the two, as I found it easier to stay with Helga as she developed and grew into herself; however, Passing was also spellbinding and intriguing, for it almost reads like a short story, yet it has the characteristics of a novel. In Passing, Irene and Clare are main characters you get to know intimately, as both women struggle with the psychological infringements upon their married and social lives. One woman decides to pass as a white woman in society, choosing to lie to her husband about her racial makeup. The other woman struggles with her friend's decision, but realizes that the truth could place her friend's life in jeopardy.

Larsen never ends a story the way you would expect - this I loved about her writing. Most importantly, I loved how she showcased race and gender identity through such an idyllic plot encompassing love and sisterhood. The book is regal in its display of such themes, reminiscent of the Harlem Renaissance era from which it unfolded. In Quicksand, Helga struggles with her own racial makeup and at times she seems to hate her own people, yet she realizes that she can't live without them, or without being herself:How absurd she had been to think that another country, other people could liberate her from the ties which bound her forever to these mysterious, these terrible, these fascinating, these lovable, dark hordes. Ties that were of the spirit. Ties not only superficially entangled with mere outline of features or color of skin. Deeper. Much deeper than either of these.

Color. Light or dark - the superficial things that consume.

-

Few writers are able to capture the sense of alienation engendered by the deeply-embedded racism of America like Nella Larsen. Larsen explores not so much the ostensible side of racial politics in America, but instead explores the more insidious nature of racism, of the deeply embedded prejudices in American society which stripped African-Americans of their humanity, of the links between this and the perpetuation of the dominance of the white population, of the little things, such as the affected condescension Helga experiences in the employment office, which gradually chip away at Helga's sense of self, until she is forced to become grateful for even the most base level acceptance. In addition, Larsen explores the tedium of constantly having to view everything via the prism of race, that whilst ethos behind self-aggrandization and the regaining of power amongst the African-American community was undoubtedly a great thing, it risked engendering a kind of collective myopia, where every aspect and problem in life becomes racial.

'Quicksand' follows the story of an intelligent if morose young woman named Helga Crane. Feeling displaced and utterly alone in the world, Helga eventually reacts to any attempt by other people to connect with her with contempt and derision after an initial, often ephemeral period of acceptance and happiness. What I like most about Helga is how flawed she is as an individual-irrespective of some of the underlying societal causes of these, her feeling of being perpetual piqued, her self-absorption and selfishness are often traits which when associated with male characters, are often viewed positively, as a kind of anti-hero,yet typically when it comes to female characters exhibiting this type of behaviour it is frequently viewed in a negative light-as well as giving an underlying rationale behind Helga's character, Nella Larsen is able to give her character depth and an a rich, if often contrarian, emotional life which evokes the reader's sympathy. Passing' is a slightly more experimental style in terms of style, with the narrative at times bordering of stream-of-consciousness and the ending-and much of the story-shrouded in ambiguity. In addition, Larsen is able to evoke and re-create the muggy, slightly claustrophobic nature of life in the ghetto, the sense of suffocation and yet, at the same time freedom it offered, its febrile and feverish atmosphere;

"Chicago. August. A brilliant day, hot, with a brutal staring sun pouring down rays like molten rain. A day on which he very outlines of buildings shuddered as if in protest against the heat. Quivering lines sprang up form baked pavements and wiggled along shining car-tracks. The automobile at he kerb were a dancing blaze, and the glass of he shop windows was a blinding radiance. Sharp particles of dust rose from the burning sidewalks, stinging the seared or dripping skins of wilting pedestrians. What small breeze there was seemed like the breath of a flame fanned by slow bellows"

Acerbic and insightful, Nella Larsen blazed the way forward for African-Americans to speak about and share their experiences, however more than this, Larsen was an brilliantly talented writer, who was able to re-create the deliriousness of Harlem as well as the quaint quiescence of Copenhagen but, more importantly, was able to create flawed, but full-realised and therefore empowered black female characters. -

I was not prepared for this. But it was probably better that way. Here are a few notes on each:

Quicksand: Stylistically, the prose is conventional, with some interesting indirectness and some surprisingly concise and fresh sounding turns of phrase. For me, the structural aspects were the more interesting part of the prose: the pacing and the lacunae specifically.

As for the content: the main character’s (Helga Crane’s) very identity suffocates her: In her America, having a white mother and black father means that bigotry and patriarchy condition her autonomy. Her resultant way of being put me in mind of Camus’ The Stranger and Delillo’s “Baader-Meinhof”. That is to say Helga rebels instinctively but gropingly. She is pulled through her life mostly against her intentions by the currents of irrational impulsivity and the cuffs of cultural normativity. She’s foolish in the way we all are, in that we act only on our always incomplete knowledge and muddy intuitions. But Helga’s braver than most because she’s willing to take big risks; she throws up her stable teaching job and fiancé and later, a life of material comfort, to escape the asphyxiation of quotidian unfulfillment on the one hand and the alienation of objectification on the other. Her final attempt at shedding despair is a mis-self-diagnosis of worldly grasping and a misprescription of metaphysics. She ultimately prefers Nietzsche to Kierkegaard, (i.e. she surrenders to “faith” but ultimately finds it untrue, deformative and nihilistic) but by that time it is too late. She finds herself crushed under the yolk of childbearing: a brutal indictment.

Passing: Should be required reading. Tighter prose than Quicksand. Everything hurts now. Liminality heaving open massive casement windows. This is a reckoning. If you only read one, make it this one. If you will read both, end on this note. -

Passing is one of the best books I have ever read. The conflicts in that novel are so complex and tightly composed that while reading it, I feel so conflicted and torn I can barely breathe. Beautiful language, fascinating story, complicated and well-constructed characters. This book is excellent in every way possible.

-

QUICKSAND (1928) and PASSING (1929) are two short, intense novels by Nella Larsen, an unjustly forgotten author from the Harlem Renaissance until the 1970's.

Both novels feature strong, unconventional and daring heroines: in QUICKSAND, cultured and refined Helga Crane has a mixed racial heritage. An illegitimate daughter of a Danish mother and an African American father, she feels she doesn't belong to neither of those worlds. She experiences loneliness and isolation. I want to avoid spoilers so I won't dwell too much on the plot, yet some things were terribly unconvincing in this novel. I will only mention two issues that left me perplexed: Helga's sudden religious "conversion" which comes out of the blue and her sudden marriage to a rural southern preacher whose "fingernails [were] always rimmed with black " and who always smelled of "sweat and stale garments". Why did Helga, who loved fine clothes, "who took to luxury as the proverbial duck to water", end up in a state of emotional and physical collapse from having too many children with a man she despises? This was Larsen's first novel, and to me, it seems unpolished.

PASSING is a much more accomplished novel. Irene, an unreliable narrator, is the perfect, nurturing,

self-sacrificing wife. She lives a very comfortable life in Harlem with her husband and two boys. Irene gives us an account of her friend Clare's life, a beautiful and calculating woman who flouts all social rules of the black bourgeoisie. Clare Kendry has been “passing for white,” hiding her true identity from everyone, including her racist husband. The perfect recipe for disaster. The ending is shocking, ambiguous and very well developed.

Larsen's writing is smart, witty and unpretentious. Her tough novels explore issues of race, identity and gender. I would definitely recommend PASSING. -

Two novellas from 1928 and 1929. I thought I had an idea about Passing at least. I thought it was going to be a little melodramatic with a contemporary look at a complex racial issue. It was much more than that. Issues of race are not glanced upon or alluded to. They sit right at the heart of Larsen's writing. There are no gentle euphemisms, there are simply two societies sitting right next to each other in 1920s New York, Chicago and elsewhere, and the only way to move from one to the other is to lie and deny your ethnicity and your origins. The advantages and the costs of "passing" are tackled head on... and there's a bit of melodrama.

But, for me, the real prize here was "Quicksand" which was even more complex. Helga has a white mother and a black father. Regardless of whether she is partying in Harlem or living with her social climbing aunt and uncle in Copenhagen she remains throughout both black and female - quicksand on quicksand - dragged under by this twofold constriction of her intelligence, her sexuality and her freedom.

It's been more than a decade since I read any Edith Wharton, but I thoroughly enjoyed revisiting this unapologetic 1920s vision of womanhood which contributed as much to my appreciation of feminism as Atwood did writing 60 years later. -

In many ways Larsen presents her female characters as Romantic heroines trapped in a Naturalist novel. As the poet W.B. Yeats has lyrically expressed, they’re “sick with desire and fastened to a dying animal.” That dying animal is embodied in many ways in "Quicksand" and "Passing," from sterile or racist environments (such as Naxos and Clare's home life with Bellew), to the fragile limitations of the female body, to the institutions of marriage and the responsibilities of motherhood. In a brutal paradox, the sordid “dying animal” can even be the desire and restlessness itself, as Larsen indicates of Helga in "Quicksand": “There was something else, some other more ruthless force, a quality within herself, which was frustrating her, had always frustrated her, kept her from getting the things she had wanted. Still wanted.” Recommended for those who like to explore the complicated issues related to race and the theme of the "tragic mulatta."

-

"'I'm beginning to believe,' she murmured, 'that no one is ever completely happy, or free, or safe.'"

—Quicksand—

Interestingly, I expected to like Passing more but vastly preferred this novel. It hits a little too close to home: lonely bookish girl grows up in the South, moves to Chicago which she likes better, and then moves abroad which she likes best. However, she feels a strange inevitable pull back to America—she knows she can't live there happily yet also can't quite stay away. She teaches and loves her students but feels empty and craves fine things. Everyone urges her to get married, but she's not in a hurry and falls in love with the wrong people. Spooky. Nella Larsen has a masterful way of crafting and expressing emotion, and I think that's the element of her work that will remain with me.

"'You don't mean that you're going to live over there? Do you really like it so much better?' 'Yes and no, to both questions. I was awfully glad to get back, but I wouldn't live here always. I couldn't. I don't think any of us who've lived abroad for any length of time would ever live here altogether again if they could help it... Oh, I don't mean tourists who rush over to Europe and rush all over the continent and rush back to America thinking they know Europe. I mean people who've actually lived there, actually lived among the people" (101).

—Passing—

I was surprised at the closeness of the 2021 film's script to the true dialogue of the book! Definitely The Great Gatsby vibes (which is always a yes from me) yet without a similar sense of endearment or intrigue towards the flawed characters. However, I would love to read/write an essay on Daisy Buchanan and Clare Kendry and this sort of 1920s "voice like money" manic pixie dream girl trope. How does this subtle or not-so-subtle equivocation with wealth relate to seeing women as possessions as well as ideas of whiteness? So fascinating. Also, the fact that both characters have a daughter (perpetuating a cycle?) yet wrestle with motherhood: Clare's "I think that being a mother is the cruellest thing in the world." and Daisy's "That's the best thing a girl can be in this world—a beautiful little fool." Now I'm thinking about Sylvia Plath's "Perfection is terrible, it cannot have children." Can you tell that I miss being an English major?

"Sitting alone in the quiet living-room in the pleasant fire-light, Irene Redfield wished, for the first time in her life, that she had not been born a Negro. For the first time she suffered and rebelled because she was unable to disregard the burden of race. It was, she cried silently, enough to suffer as a woman, an individual, on one's own account, without having to suffer for the race as well. It was a brutality, and undeserved. Surely, no other people so cursed as Ham's dark children" (225). -

These two short novels by Nella Larsen explore issues of identity, freedom, and belonging in the Black American experience through the stories of young women in the 1920s who are trying to navigate the world in which they find themselves. Although the two stories are quite different, both feature female protagonists who are vivid and memorable. I found Passing to be the better of the two books, but I enjoyed and learned from both of them.

The heroine of Quicksand, Helga Crane, is a young biracial woman from Chicago who, when we meet her, is teaching at a school for Blacks in the South. After hearing a white preacher in the school’s chapel remind the students of “their duty to be satisfied in the estate to which they had been called, hewers of wood and drawers of water,” she’s had enough and decides to return to Chicago. (The school and its chapel service reminded me of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.)

But Helga’s return to Chicago proves to be just the first of several moves that she makes over the next few years as she searches for her place in the world. She tries Harlem, but despite feeling “free” at first, she soon tires of “all the talk of the race problem” and begins to despise the dark people around her. She next travels to Copenhagen and lives with her white Danish relatives, where she is welcomed and feels an “augmented sense of self-importance.” But she also becomes aware of being seen as “exotic” and, to her surprise, finds herself being homesick for America and the “brown laughing faces” in Harlem.

Helga returns to Harlem and enjoys being with her own people. But she is still not fully at home. She realizes that her life is divided “into two parts in two lands, into physical freedom in Europe and spiritual freedom in America.” But does it always have to be one or the other? Can she ever find a life where she can be fully at home?

Helga does have one more move to make, one last pivot to a different life. Unfortunately, her decision didn’t ring true to me, and it lowered my overall opinion of Quicksand. But Larsen’s beautiful writing and her vivid portrayals of Helga and the people around her will still remain with me despite the book’s disappointing ending.

Passing is the story of Irene Redfield and her childhood friend Clare Kendry. Both are beautiful light-skinned mixed-race women, but they have taken different paths in their lives in terms of race. Irene has embraced her Black identity, married a Black doctor, and built a life with her family in Harlem. When she unexpectedly runs into Clare after a dozen years, she finds that Clare has chosen to hide her “colored” identity, “pass” for white, and marry a white man.

Clare’s husband, Jack, is an outspoken racist. When Irene first meets him, he shocks her by referring to Clare—humorously, to his way of thinking—by the nickname “Nig” (because he thinks her complexion is getting darker as time goes on, not because he suspects she is anything other than white). When Irene asks if he dislikes Negroes, he replies, “‘You got me wrong there, Mrs. Redfield. Nothing like that at all. I don’t dislike them. I hate them. … They give me the creeps. The black scrimy devils.’” Irene controls her anger, but she vows not to see Clare anymore. Irene values security, and she fears that Clare will upset the security that she has been enjoying with her husband Brian and their sons.

But Clare has other ideas. She admits to Irene that maybe Irene’s way of life is wiser and happier than hers. She begins to insinuate herself into Irene’s life. Irene worries that Clare may have designs on Brian, which Clare does not dispel when she admits, “‘Why, to get the things I want badly enough, I’d do anything, hurt anybody, throw anything away. Really, ‘Rene, I’m not safe.’” Irene dwells on the thought that Clare is trying to steal her husband, even though she has no tangible proof at all. She feels that she is suffering doubly, both “as a woman, an individual, on one’s own account, [but also] having to suffer for the race as well.”

As Clare spends more and more of her time in Harlem, it seems less and less likely that she will be able to continue to maintain her “passing” charade. Clare hardly seems to care, but for Irene, the suspense she feels as she worries that Clare will overturn the security of her world becomes unbearable.

As in Quicksand, Larsen’s writing in Passing is brilliant, and she again demonstrates her great skill at character development. As I said above, I think Passing is the better of the two books. The dynamic between Irene and Clare provides an ideal structure through which Larsen can explore the issues of racial identity and community that are her concerns in both books. I highly recommend either or both books, but since I’m reviewing them together, let me clarify that I would give Quicksand four stars and Passing five stars. -

Quicksand - 3.5

Passing - 4.5 -

Coming-of-age, woman as child, young woman with all the potential of a child until she foolishly marries an ugly man for a house, for God, for the chance to give up responsibility for her own foolishness.

Helga Crane goes from Naxos, a prestigious school dedicated to Negro uplift - call it the nonprofit sector - to suddenly realizing that she hated the hypocrisy of do-good work. When she quits Naxos at 23, declaring how much she hates it, her boss calmly looks at her and says, " Twenty-three, I see. Some day you'll learn that lies, injustice and hypocrisy are a part of every ordinary community. Most people achieve a sort of protective immunity, a kind of callousness, toward them. If they didn't, they couldn't endure. I think there's less of these evils here than most places, but because we're trying to do such a big thing, to aim so high, the ugly things show more, they irk some of us more. Service is like clean white linen, even the tiniest speck shows."

The joke being that Helga Crane leaves the world of service forever in search of something even cleaner, more beautiful, and she occasionally finds it in great luxury, in being served. She is a young woman dedicated to having as much of the beautiful world as possible, never quite confronting the horror of limitation.

At the end, giving birth to her fifth child, she has become a slave to the extra mortality of a woman's body. She has to have babies, raise children, be a wife, until she dies. This was her choice, her choice to lead a normal life that leans into the pain of ugliness by first going into God in a very superficial way, by deciding to become a believer instead of suddenly believing. Her second method of leaning into the pain of ugliness is to marry someone ugly but powerful in a very limited circle, a provincial Southern preacher. With him she can limit her world to what might be expected of her; children, wife, husband, a small clan of loyalty, a lesser and superficial loyalty to Christians. Helga Crane attempts to keep that world beautiful too, fixing up the parishioners' dowdy little bows on their dresses, but she ends up in the smallest world, trapped in her bed, unable to even keep awake but for a nurse, an expert in bodily pain, who declares her to be alive.

-

These two novels were really fascinating. They explored issues facing African-American women during the Harlem Renaissance era, particularly light skinned women. There is a tremendous emphasis on liminal figures in these books--African-Americans marginalized by race, lesbianism repressed and projected, and individuals passing between race and through sexualities.

Quicksand:

https://youtu.be/ErsAwdZjHP8

Passing:

https://youtu.be/XgLryum2bY8 -

Read these novellas a number of times over the years. They were a big part of my master's thesis about mixed race Af-Am women and the concept of the "cyborg", a being existing within apparently contradictory identities.

-

I really enjoyed reading both of Nella Larsen's stories and I love the way she writes. She is a very skillful writer, you only have to read a few of her well crafted sentences to see that writing comes naturally to her.

The way she created the 'tragic heroine' or 'tragic mulatto' as was the term attributed to such protagonists in those days, was very touching. You couldn't help but feel for the heroines and what they were going through. You're happy when they're happy, torn when they're torn and both stories are so touching, especially Quicksand.

The agony of whether or not to 'pass' for white and the tragedy of being stuck in a loveless marriage - all of these themes pulled at my heartstrings.

Helga Crane's story is a particularly haunting one, and one that resonates with me to this day, probably because of the idea of being trapped and unhappy, yet having no choice - she had to do what was best for her family. This is probably the most tragic of the 'tragic mulatto' stories I have read from the Harlem Renaissance - and this is a triumph on the writer's part. To this day, I still remember this story so clearly, although I read it donkey's years ago! Larsen shows that beauty can be a curse, and having everything on the surface, does not mean that a person would be happy. In this case, Helga is desired because of her beauty, whereupon she becomes a possession for men to gawk at. Yet deep down inside, she is never really happy.

What really swings it for me though, is Larsen's writing style; so evocative, visual and sensuous, her descriptions (especially of the heroines) will blow you away, as well as the way she brings to life their surroundings.

I'm even more in awe of her, as some of these stories were loosely based on her childhood and growing up as a woman of mixed heritage (mixed-race), torn between two separate worlds. What really got me was the very prevalent themes of sexuality and 'otherness'. The idea of the heroine being seen as 'exotic', 'wild' and 'highly sexual' by white/non-black men, because of her dark skin and curly hair. Very interesting insights indeed and the writer had my attention throughout both stories.

It's sad that Larsen did not have a very happy childhood/romantic life and her work did not gain the recognition that it truly deserved. However for me, Larsen will definitely go down as one of my favourite writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Someone should make a film of both stories. I would love to watch it! -

Not an easy read nor a happy one. Best not to read the introduction first (why do they always give away the ending?), but it helps you understand why Larsen made some of the choices she did. We had a great week in class discussing this book. It opened up a lot of students' eyes about the peculiar racism and sexism that mixed-race women have experienced (and continue to).

-

Great learning experience for me as far as being in the head and heart of a bi-racial woman living in Harlem during the Renaissance (20s and 30s), but though I fully appreciate the tenacity and talent it must have taken Nella Larsen to write such novels in those days and the sacrifices she had to endure later, dying in anonymity as a nurse in New York, I still found the books a little too forgettable for what I was expecting.

I disliked both narrators: Helga (Quicksand) and Irene (Passing), and for the same reasons. But then again, I do understand why both women were much mentally divided and easily shaken or even so quick to despair. However, the misery of their inner worlds wasn't countered by vivacity of spirit or bursts of courage or anything like that, which usually makes for memorable heroines. As I write this, I realize that maybe Nella Larsen did something very original in that she allowed her black heroines to be complicated intellectuals with snobbish penchants. Maybe that in itself is worth talking about.

Food for thought. As I grow older and wiser, I might return to this book and add another star. -

After reading these two powerful short stories, Nella Larsen is now up there with one of my favorite authors. Both stories beautifully depict the restless and beleaguered spirit of smart, young, black women in 20th century America. What is so striking is how much I related to the feelings, emotions and internal battles of the characters. Despite it being of another time, I think many women, especially women of color, will resonate with the suffocating limitations of race, class and gender that the characters face. In 21st century America much has changed, but much more still has not.That's why Larsen's stories are still so profoundly relevant today.

-

the harlem renaissance is the only historical era i care one whit about, and these two novellas represent some of my favorite writing from it. i re-read them often. i think they're incredibly evocative and mercurial; for a long time, i've had a fantasy of writing a treatment of *passing* as a full-length film. but i'm too lazy.

-

Betoverend boek met een paar uitzonderlijke passages. Een pleidooi voor kleur.

Klik hier voor een videorecensie van Drijfzand op mijn Youtube-kanaal De idioot leest. -

Er nooit echt bij horen

Nella Larsen (13 april 1891 - 30 maart 1964) was een schrijfster in de Harlem Renaissance, een artistieke Afro-Amerikaanse schrijvers- en kunstenaarsgroep die in de twintiger jaren van de 20e eeuw was ontstaan.

Ze was van gemengd bloed, met een van oorsprong Deense moeder en een gekleurde vader uit Deens-West-Indië, een kolonie in de Caraïben die destijds behoorde aan Denemarken.

Toen haar vader overleed, trouwde haar moeder met Peter Larsen, een Deense man die Nella haar nieuwe achternaam gaf. Nella kreeg er een halfzusje bij waardoor ze de enige kleurlinge in het gezin was. Dit halfbloed zijn gaf haar een gevoel van minderwaardigheid en niet weten waartoe ze behoorde. Daar haar biologische vader ook blank bloed in zich had, was ze geen neger en geen blanke. Ze kon ook doorgaan voor een blanke als voor een zwarte.

Het woord neger wordt letterlijk gebruikt in de twee novellen, een woord dat in die tijd algemeen gebezigd werd.

Zowel in de novelle Schutkleur als in Drijfzand beschrijft Larsen een deel uit het leven van een vrouw die - net als Larsen zelf - zeer licht van huid is en voor blank of kleurling door kan gaan.

Helga Crane, de jonge, ijdele lerares uit Drijfzand, is ook dochter van een Deense moeder en een Deens-West-Indische vader. Mooie kleding, fijne stoffen in felle kleuren en mooie spulletjes hebben haar voorkeur. Rusteloos als ze is neemt ze op stel en sprong ontslag, en na wat losse betrekkingen en omzwervingen reist ze op advies van haar oom naar Denemarken waar ze met blijdschap onthaald wordt door de zus van haar overleden moeder. Ze is er meer dan welkom, maar Helga lijkt in alles op twee benen te hinken; terug naar haar zwarte medemens in Harlem of blijven in het vrije blanke Kopenhagen, waar ze door iedereen wordt geaccepteerd zoals ze is, maar waar ze steeds het gevoel blijft hebben dat ze er niet helemaal bij hoort. Steeds gedreven door wat het hardst aan haar trekt zijn de tegenstellingen hierin levensgroot. Uiteindelijk zorgt het huwelijk van een vriendin ervoor dat ze toch de oceaan weer oversteekt en haar geluk zoekt in beloftes. Maar ook dan voelt ze dat het niet is wat ze wil.

In de novelle Schutkleur staan Irene Redfield en Clare Kendry centraal. Beiden gaan als halfbloed door het leven, maar weten op een geraffineerde manier van hun kameleontische uiterlijk gebruik te maken. Net hoe het ze uitkomt, gedragen ze zich als blank of als zwart.

Clare is echter getrouwd met een blanke, racistische man die er geen weet van heeft dat zijn vrouw negerbloed heeft en dat haar oude schoolvriendin eveneens een halfbloed is en getrouwd met een neger. Clare's grootste zorg was dat ze een zwart kind zou krijgen, waardoor ze ongenadig door de mand zou vallen. Het dansen, de feesten en bijeenkomsten in Harlem trekken haar enorm aan en ze weet steeds een manier te vinden om haar man om de tuin te leiden.

Irene's zwarte man is wél op de hoogte van het feit dat zijn vrouw negerbloed in zich draagt en van hun twee zonen is de één zwart als vader en de andere blank als moeder.

Ook in deze novelle is er sprake voortdurend tegenstrijdige verlangens bij de vrouwen die niet goed kunnen kiezen waar ze loyaal aan (willen) zijn. Uiteindelijk zal het leiden naar een gruwelijke climax wanneer Irene het gevoel heeft dat haar huwelijk onder spanning komt te staan.

Het autobiografische gehalte in beide sublieme novellen is hoog. Rassensegregatie nog altijd een griezelig actueel onderwerp.

Larsen's verteltrant is allesbehalve gedateerd en leest bijzonder fris. De protagonisten, die moeten omgaan met rassenhaat, vooroordelen en hypocrisie, hebben een grote psychologische diepgang en zijn magnifiek uitgewerkt. Klassieke pareltjes die onderdeel zijn van de Schwob-lijst en het verdienen om nooit vergeten te worden.

Larsen heeft haar studie deels in de VS en later in Denemarken gevolgd. Bij terugkomst in de VS werd ze verpleegster in New York, gaf ze les aan de universiteit. De ideeën van Booker T. Washington, die zich hard maakte voor betere rechten en kans op ontwikkeling van kleurlingen, bereikten ook haar. Ze trouwde met een zwarte man, ging wonen in Harlem en aan het werk in een bibliotheek wat waarschijnlijk de aanzet is geweest om meer te gaan lezen en haar ook de pen deed oppakken. Een scheiding volgde toen ze ontdekte dat haar man haar bedroog met een blanke vrouw.

Door haar affiniteit met de Afro-Amerikaanse cultuur waren de banden met haar familie verflauwd. Helaas heeft een valse beschuldiging van plagiaat ertoe geleid dat ze zich terug heeft getrokken uit de Harlem Renaissance en haar pen aan de wilgen heeft gehangen. Depressies waren de reden dat ze steeds minder deel nam aan het sociale leven en op de leeftijd van 72 jaar overleed ze.

Titel: Drijfzand & Schutkleur

Oorspr. titel: Quicksand & Passing

Auteur: Nella Larsen

Vertaling: Lisette Graswinckel

Pagina's: 320

ISBN: 9789046822951

Uitgeverij Nieuw Amsterdam

Verschenen: januari 2018 -

Iemand vanuit de Nederlandse Fanatieke Lezers (FNL, groep op Goodreads) zette me op het spoor van de Netflix Book Club. In november 2021 staat hier het boek Passing centraal. Vanaf 10 november is de film te zien op Netflix. Nieuwsgierig geworden door deze tip ging ik op zoek naar het boek.

In het Nederlands verscheen het boek Schutkleur samen met het boek Drijfzand. Het zijn Amerikaanse klassiekers die oorspronkelijk in 1928 verschenen. En alhoewel het thema van beide boeken vergelijkbaar en interessant is, konden de boeken me matig bekoren. Reden hiervoor is vooral de afstandelijke schrijfstijl. De schrijver koos ervoor om te schrijven vanuit de derde persoon enkelvoud wat maakt dat je als lezer op afstand het verhaal volgt in plaats van het te beleven. Verder werd in het nawoord in enkele alinea's een toelichting gegeven op de auteur, de boeken en de context. Hiermee was het nawoord voor mij informatiever dan de boeken zelf.

Ben heel benieuwd hoe dit zich vertaalt naar een film en ga dan ook zeker kijken. -

Nella Larsen did not produce much fiction: these two novellas and some short stories comprise all of her published work. I felt that the novellas Quicksand and Passing were the work of a writer who had not quite reached the height of her powers. That being said, they're both very strong, Passing in particular. Quicksand meanders a little too much, without getting to the heart of its central character, but Passing is a deft, insightful piece of work, with a twist I wasn't expecting. Both novels, set and written in the late 1920s, deal with being mixed race, and of Black people "passing" as white. They explore a sense of rootlessness or detachment experienced by their main characters because they are mixed race. They give an insight into Black culture at the time, and especially into the experiences of middle-class women. Definitely worth checking out.

-

What great books they are. Passing, the sevond novel in this book I read in one day. I was completely taken by the book, finding out this meaning of passing. Had no idea, really. It was a very interesting read, both because of the information, sphere of America in the 1920. A place and time completely foreign to me. And yet I felt strangely at home both with Passing, as well as with Quicksand. The emotions described seem to be universal, transgressing physical borders, time differences as well as racial lines.

Despite I liked Quicksand a lot, I didn't really sympathize with Helga a lot. I guess that's because of the narrative, 3rd person. I followed her search, her longing with interest, but didn't feel outrage or real sympathy for her at all when she, finally settling down, finds out how hard a woman's life may be. -

Oh man. Both of these were hard to read, not because they weren't well-written (they were), but because they made me so angry. If you'd like to explore two of the ways that gender and race intersected for Black, American women in the early 20th century, these are very much worth your time.

In both books, Larsen explores the inner lives of fairly affluent black women living in the North. Though they're free from Jim Crow laws, they still exist within the ironclad confines of race and gender. Both women beat against the bars like birds in a cage, and watching is agonizing. But the characters are so finely drawn, and the language so graceful, it's a pleasure to read. -

I finally read this (only Passing). The amount of racism and fear—violence just below the surface—is incredible. Jealousy among the women as well. The men, both black and white, see, to have control over the women. So many themes in addition to the destructive impact of racism. Is Clare trying to get her identity back? Larsen shows us that is impossible.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/02/t-...