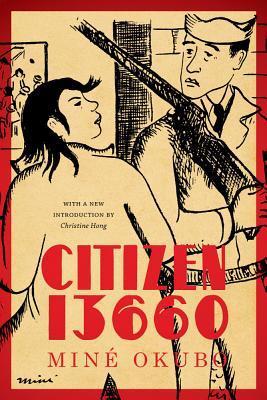

| Title | : | Citizen 13660 |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0295993545 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780295993546 |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 209 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1946 |

| Awards | : | American Book Award (1984) |

"[Mine Okubo] took her months of life in the concentration camp and made it the material for this amusing, heartbreaking book. . . . The moral is never expressed, but the wry pictures and the scanty words make the reader laugh - and if he is an American too - blush." - Pearl Buck

"A remarkably objective and vivid and even humorous account. . . . In dramatic and detailed drawings and brief text, [Okubo] documents the whole episode . . . all that she saw, objectively, yet with a warmth of understanding." " - New York Times Book Review"

Citizen 13660 Reviews

-

Citizen 13360 is an early example of what might be seen as a graphic novel based on drawings the author did of her time incarcerated in two concentration camps as part of the shamefully racist Japanese internment or “protective custody” that took place on the west coast of the US during WWII. As we study that war, as many are doing now, Americans are generally characterized as liberators, as part of the Allied efforts that defeated fascist and racist regimes, principally Hitler’s Nazi Germany. Yet, and especially in the face of current American racist and anti-immigrant rhetoric and practices, as we see shameful family separations and incarcerations it is important to recall that we have done these kinds of things before.

Miné Okubo was studying in Europe on an art fellowship when war was declared in 1939. She managed to make it to the US, and went to live with her brother, a student at UC-Berkeley. Then the US declared war on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor and President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9022 in 1942. Miné and her brother were “relocated” and imprisoned with thousands of others—the majority of which were American citizens--in an “internment” camp: “My family name was reduced to No. 13660.” She and her brother wore this number, and all their (few allowed) possessions were tagged with this number.

They were required to live in a former horse stall in a stable. The camps were hastily readied, which is to say the conditions were appalling. But Miné, an artist, denied the use of photography to document what was happening, produced more than 2,000 drawings in the time of her stay in the camps, selected some of them to create a story, added a written narrative, and over time expanded her story. The book she created out of this documentary art (such as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by Walker Evans and James Agee) was published by Columbia University Press in 1946 and was an immediate sensation. It went out of print in the fifties and sixties as some people wanted to “forget” the war, but Japanese American “never forget” movements led to new editions in 1973, again in 1983 and once again in 2014.

The work is important as one person’s quiet record of concentration camps (ironically) used in the US even as it was engaged in efforts to liberate concentration camps in Europe. Over time there was more freedom in the camps, more fluidity with respect to access to material needs, but the conditions and the basis for incarceration remained unacceptable.

The work is not that emotionally engaging—one dimension of the book is a kind of calm stoicism, and another is a kind of humor she and others bring to the situation—but it’s a remarkable document, an important part of America history. It has an “objective” feel to it, not intended to be sensational: This is what happened in our country. It can "happen here" and did. As with Joe Sacco's work, this is comics journalism, comics history, a first person account of life in a Japanese internment camp. Miné is in every drawing, emphasizing herself as witness. That the title identifies her with the dehumanizing Nazi practice of quantification—as a woman of Japanese descent she’s not a name but a number—is telling and sad. Never again? What’s happening right now in this country and the world?

Here’s some examples of the kind of artistic approach she used:

https://www.skirball.org/exhibitions/... -

This graphic documentation of the 'protective custody' that many Japanese Americans had to submit to was done by a young woman (Mine Okubo) who was there. The differing ways individuals try to come to terms with their new "status" in a country they thought they belonged to is truly sad...a lesson we should never forget.

-

I've had a real crisis of faith since the election. How do I tell my students to be honest and decent, work hard and treat people right when none of those things are rewarded? When the highest office is held by a person who is proudly mendacious, cruel, petty, lazy, incurious? Who in turn rewards people who are the same?

My teaching has taken a turn. My 7th graders are currently reading Citizen 13660 and connecting it to NSEERS, executive orders banning Muslims, and anti-immigrant rhetoric. -

This graphic memoir of life for a young Nisei woman in the internment camps during WWII was published shortly after the war, and considered an important document of this shameful period in American history. Cameras & photography were not allowed in the camps so Okubo's book remains one of the few visual representations of evacuee life from the period created by an actual evacuee.

Each page is a single panel drawing with a written caption underneath. Okubo's lines are spare, graceful and very expressive. Interestingly, she includes herself in every page, intentionally highlighting her role as narrator & observer of each scene.

Along with Maus & Barefoot Gen, this is one of the definitive comics about the war & its aftermath.

Highly recommended for all Americans, especially those who don't know about the internment camps. Good pick for older kids and teens as an introduction to the subject. In the 1983 introduction, Okubo writes, "I hope that things can be learned from this tragic episode, for I believe it could happen again." Sadly, this work seems just as timely now as it did when first published in 1946. -

A beautiful blend of history, graphic novel, and story telling. Citizen 13660 is the story of Mine Okubo and her life at two japanese internment camps after pearl harbor. Her fantastic drawings bring to life the daily activities and hardships they endured. The resourcefulness of the people is fascinating, watching them create everything from furniture to gardens from next to nothing is inspiring. The human spirit really shines in this book and although the idea of the camps is cruel and unjust, the book doesn't focus as much on that aspect but shows what they accomplished and overcome.

-

The use of the nine blank pages was rather ingenious as it gives the impression that what it written is impossible to portray with any accuracy. The reader is forced to try and imagine something that can not be shown in a picture, or even a photograph. The reader has to consciously apply themselves to what was read and so the point being made is more prominent and driven home to the reader. First blank page, 11, shows the absence of her father and leaves both the main character and the reader at a loss to understand why. The next blank on page 13 seems to show just how quickly they had left and how abrupt it had been for them. Page 16 has no picture because how could anyone portray 110,000 people in a single image much less give the feeling of so many, most people have never even been in a group larger than about five hundred. The fourth blank is on page 118 and describes perfectly the emptiness of the land they were traveling through and makes the reader wonder after reading the last line of the page "The meals on the train were good after camp fare."

Page 128 which shows the rooms they had been given to live in is followed by a plank page with illustrates how much they really had. Page 138 adds to the feeling even more as the text tells of how they had divided the space even further. Page 176 is just the perfect illustration as the first sentence is the end of the one from the page before and reads "thereby made themselves stateless persons." The second to last blank page is on page 200 and is somewhat chilling to read at the text tells of how the teenagers fought to stay and not lose all they had gained by being labeled disloyal. The final blank is on page 206 and I feel it was a wonderful choice as the text reads :"In January of 1944, having finished my documentary sketches of camp life, I decided to leave." The blank was masterful in that is showed that she was done, there was nothing more to draw and so there was nothing drawn. -

Perhaps it's obvious to state but one doesn't read this book for the prose. The writing is, in fact, a bit terse and lacking in color and imagination. I suppose you might say the tone perfectly matches the author's experiences living in internment camps. Okubo certainly doesn't romanticize the poor and thoughtless conditions that these communities were forced into. All of her observations are stated matter of factly, much like the accompanying images. A solid, no-frills book. I feel ready to read No-No Boy now!

-

I didn't find the prose or the art especially striking, though I might if I read it again. Where I found the most value in this was in reading about the monotony of the camp, of the day-to-day acceptance of a set of awful conditions, and just making the best of them because you have no other choice. It's heartbreaking, and this novel has reminded me of a part of history that's (unfortunately) easily forgotten, and prompted me to read more about it.

-

When I was a kid, I read comic books, lots of them and all kinds – everything from Archie to Superman. So I know the power of putting together graphics and text. And I have to confess, that when I was in school, we could still find Classics Illustrated* in second hand comic stores and I may have actually used one or two of these for book reports. But today, all kinds’ graphic books are available, of considerably better quality than Classics Illustrated were and very popular among readers of all ages. Now, more and more graphic books are being written and published that cover important aspects of history and, in the same way Art Spiegelman’s Maus books are used in schools to study the Holocaust, Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660 is an ideal vehicle for presenting a different aspect of World War II to students.

Miné Okubo was studying in Europe on an art fellowship when war was declared in 1939. She managed to get herself to the home of some friends in Berne, Switzerland and after a long wait and many difficulties, finally obtained the necessary papers she needed to travel to France. From there, she set sail for the US on the last boat out of Bordeaux. Shortly after Miné arrived back in the United States, her mother passed away and she went to live with her brother, a student in Berkley, California.

Things went well for them, even when the US declared war on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. But as suspicion and fear grew, President Roosevelt was forced to issue Executive Order 9022 in 1942. Miné was required to report for an interview that would lead to her eventual relocation in an internment camp: “As a result of the interview, my family name was reduced to No. 13660.” (pg 19 left below.) The Okubo siblings were then issued a number of tags to use for their belongings and themselves with this number.

They were scheduled to leave on May 1, 1942 for the Tanforan Assembly Center at the race track in San Bruno, California. At the camp they were assigned a former horse stall in a stable to use as their living quarters, with no privacy or conveniences (pg 35 below right.) It was here that Miné decided to use her talent as an artist to record the day to day life and small events in an internment camp.

On September 16, 1942, Miné and her brother were relocated again, this time to the Central Utah Relocation Center called Topaz. Conditions here were somewhat better, and eventually restrictions were loosened making life more bearable until they finally left.

Citizen 13660 is the first personal account of what life was like for people in a Japanese internment camp. It was originally published in 1946, but went out of print in the 1950s when people wanted to forget the war. By the 1960s and early 1970s many Sensi, or Japanese-Americans who were born in the camps, were incensed about what had happened to their parents and grandparents and that it had all been forgotten, brushed under the rug, so to speak. Wanting to understand more about their historical past in the US, these students were a moving force behind the establishment of Asian Studies programs as part of many university curriculums. One of the results of this was a reprinting of Citizen 13660 in 1973 and again in 1983.

The structure of the book is similar to a picture book. Each page has one graphic with text below it. Each graphic is done in black and white, some are done in great detail, and others are simpler, while text can range from one line to very extensive. Miné is in every graphic, reinforcing the idea that she has witnessed what she draws and writes, and never relies on rumor or hearsay. The loss of her family name for a number sets the tone of this memoir, which is decidedly impersonal factual reporting. Aside from the author, the reader never learns the name of any other person not even that of her brother reinforcing the feeling of invisibility the Miné must have felt. Ironically, this objective technique proves to be a very effective style for conveying the feelings of the internees, their anger, confusion, disgrace, humiliation, injustice, loss and even patriotism, resulting in a very emotional document about this period in American history. It is not surprising that this technique works for her – Miné Okubo once described herself as “a realist with a creative mind.”

The National Park Service has provided information on Tanforan Assembly Center at the National Park Service Confinement and Ethnicity

More information about the Topaz Internment Camp at the Topaz Museum

Miné Okubo passed away on February 10, 2001 and her obituary may be found at Miné Obuko; Her Art Told of Internment

This book is recommended for readers aged 12 and up.

This book was borrowed from the Hunter College Library.

For those who don’t know about Classics Illustrated, they were a series of comic books, which were adaptations of classic literature. I remember using this one in 7th grade (the other one was Black Beauty; I did go back and really read The Red Badge of Courage, but not Black Beauty) -

It is of utmost importance for survivors of trauma, like the Japanese who endured the racist and violent internment during World War Two, to tell their own stories. The book's greatest success was Okubo's drawings of her life in the camps from 1942 until 1945 (she is primarily an artist), which are evocative, informative, sometimes bitter, sometimes joyous, and—this needs to be said—amazingly great at eluding the grips of censors as she was released from her camps.

Published in 1946, Citizen 13660 was the first account of Japanese internment which was told from a survivor's perspective and which showed what was really happening in these concentration camps (as FDR and the government called them): forced assimilation, starvation, unsanitary conditions, exploited labor. The list can go on and on.

My one problem with the book was that it becomes apparent that, overall, Okubo believes Japanese internment was merely a minor blot on American exceptionalism, "freedom," and "democracy" and not another manifestation of American genocidal colonialism, which continues until today. But maybe that was a way to avoid censorship. Hmmmm. -

This is a graphic journal documenting the evacuation and internment of the author, Mine Okubo in the early 1940s. It is widely recognized as an important reference book on the internment of the Japanese in the United States during World War II. The journal, which describes the day to day lives of the confined people, includes over 200 of her sketches (cameras were not allowed in the camp). This record of the struggles and indignities of bewildered and humiliated people, is told without bitterness and with dashes of humor. A quick and powerful read. Quite simply, a masterpiece.

-

Mine Okubo recorded her experience in US Government concentration camps for Japanese and Japanese Americans during WWII, first at the San Francisco racetrack (not kidding) and then, the "permanent" residence at Topaz in Utah. The unique thing about her account is that it is told entirely in pictures, another graphic novel-memoir. Mine's book, taken from over 10,000 drawings, was first published in 1946 and has been in print ever since. She tells a story which could be heavy-handed, in a very sublime way. Highly recommended.

-

Even though I have Japanese ancestry, my family was not personally effected by the WWII era Japanese internment camps since my mother immigrated here in the 1980’s. This graphic memoir was an eye opening and heartbreaking illustration of the hardships experienced in those camps. This is a very timely book that I think every American should read regardless of their race. Let’s not let history repeat itself.

-

This book was okay. It wasn't horrible, it wasn't the best thing I have ever read, but I enjoyed it enough to finish it. The only reason I didn't like this account of the internment camps during WWII, was because of how objective it was. The author barely, if at all, dove into what she was feeling during all of this. That was my only gripe with this book. Other than that it shed some light on that horrible time in our history, which I liked.

-

Okubo was an artist who used her drawing skills to visually document her World War II incarceration experience. This shows the harsh living conditions Japanese American people had to endure because they looked like the enemy. The writing style is very spare and reminds me of how many Nisei recalled their "camp" stories.

-

These drawings by Miné Okubo are about her time in internment camps during WWII. It's not a graphic novel in the modern sense but it was an early graphic memoir and an important and shameful part of American history. It's largely non-linear and full of humor and emotion.

-

Very interesting read. I'm amazed when I read stories like this for two reason. One, this didn't happened very long ago. Two, white men think they can rule everything. Sad, I know, but very true.

-

Miné Okubo’s 1946 work Citizen 13660 has the unique distinction of being both one of the early American graphic novels and being a powerful first-hand testimony to the Japanese imprisonments during World War II in the United States. Okubo – a thirty-year-old Californian with an MFA from Berkeley and a career with the Works Progress Administration – was imprisoned from 1942 to 1944 at the Tanforan Racetrack and then the Topaz War Relocation Center. An artist by trade and education, Okubo used her considerable talent to document the experience of the imprisonment, culminating in Citizen 13660, one of - if not the – first testimonies of the experience.

Despite later being involved in efforts to compensate Japanese-American who were unjustly detained as a result of FDR’s Order 9066, Citizen 13660 is, rather surprisingly, free of explicit resentment or hatred. A modern reader reading Okubo’s experiences should be filled with righteous anger (at least, I was), but Okubo herself describes the experience with an almost fatalistic apathy, a ‘what are you going to do about it’ mentality. Indeed, from her perspective, most of those detained remained loyal to the United States, and were even asked to serve in the United States Army (after passing the prescribed loyalty tests.)

For the historical value alone, Okubo’s work deserves to be read. George Carlin once used the detention of Japanese-Americans as part of a wonderful monologue (“you have no rights”), and 13660 drives this point home. We must always guard against our reflexive fearfulness of “the Other”, because the same damn problem is going to keep rearing its ugly head, generation after generation. In the light of the current Administration’s xenophobia – be it the conflation of Latin American immigrants with MS-13 gangsters or its ham-handed attempts to ban Muslims from flying into America – it serves as a potent reminder of the worst devils of our nature.

The reprinted edition I read contains a new foreword by Christine Hong, which provides excellent context – both culturally and historically – with the one downside of being written in dense academic style (I suspect it was someone’s paper at some point). Crucially, Hong made a very important argument in favor of the use of the term “imprisonment” in favor of the more common “internment”. Internment, Hong convincingly argues, has a specific legal definition, referring to the detention of foreign nationals with whom a country is in a state of war. About two-thirds of those sent to detention centers within America were American citizens, who could not have been legally be “interned” under American law. Imprisonment, indeed, is a much more honest term. Okubo’s work is peppered with other euphemisms, such as “relocation” and “evacuation”, which increasingly take on an Orwellian abuse of language. The historical record deserves better than such wordplay. -

"Citizen 13660" is one person’s personal account of their internment experience, named Mine Okubo. It is named after the number assigned to her family unit.

Contained within the pages are over 200 pen and ink sketches, which she drew during her time at Tanforan Assembly Center and the Topaz Relocation Center.

Accompanying her drawings are brief explanatory passages. Her narrative is very objective, and lacks the emotional trauma one would expect. Any hint of bitterness, or any other sentiment, is absent from its pages.

I suspect that this was because Okubo wanted this book to be accessible to as large an audience as possible. By 1981, when the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Interment of Civilians was established, this book had already been recognized as an important reference on Japanese Internment.

Okubo not only testified before the commission, but also presented a copy of Citizen 13660 to them.

Why I picked it up: I read "Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans During WWII" earlier this year, and this title was one of the works referenced. Since it was one of the first personal accounts of Japanese Internment, I was very interested in checking it out.

Why I finished it: This was a very straight forward narrative, and I found it very easy to read. It didn't take long at all to finish it, especially with all of the half-page illustrations.

Who I’d give it too: I’d give this to history buffs, those who like documentary art, and anyone interested in learning more about Japanese Internment.

Happy Reading!

1984 American Book Award -

I'd pretty much given up on finding a copy of this one to borrow, when suddenly, the Interlibrary Loan came through again! Sure, it took 4 months, but it's better than nothing, right? I just think it's funny that this book was published by the University of Washington press, yet they had to go all the way to Spokane County to find a copy to borrow.

Anyways, the art and design on this book reminded me more of a kid's picture book than the more classically comic stylings of the others I've been reading. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say that it reminds me of those creative writing homework assignments you would get as an 8 or 9 year old, where you had to draw your own picture in the top, blank half, and write about the picture in the bottom, lined half.

This book is a full and interesting snap shot of what life was like in the Japanese Internment Camps during WWII, and I learned much I didn't know about their situation and way of life. But it's just that - little snapshots of moments in time and experiences. It all felt very factual, and not as emotional as I might have wanted. I felt about Mine much the way I felt about Marjane in

Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood - sympathetic, but disconnected emotionally. -

Mine Okubo was an art student in Europe when WWII began. After rushing home to Berkeley, Pearl Harbor forced her and a hundred and twenty thousand other Japanese-Americans into "protective custody"- barbed wired camps where men, women and children lived in former horse stalls and hastily built barracks in remote desert locations. Okubo documented her difficult war years with these many line drawings and captions. She matter-of-factly describes the humiliations, the frustrations and even the humor of what it felt like to be uprooted from normal life and forced into crowded camps guarded by armed soldiers and watch towers. Okubo's work is a fascinating glimpse into what life becomes for an American citizen who is arrested because her face happens to look like that of the enemy. Published in 1946, Citizen 13660 was the first published account of the internment of the Japanese-Americans, the majority of whom were American citizens, many who had never been outside of their American home towns.

-

Citizen 13660🍒🍒🍒🍒

By Mine Okubo

Reprinted 1945/ 2018

University of Washington Press

February 19, the day the Executive Order 9066, issued by FDR, has been named Remembrance Day by the Japanese Americans, to honor the memory of relatives interned to camps. Executive Order 9066 ordered the mass evacuation from the West Coast and internment of all people of Japanese descent.

"In the history of the United States this was the first mass evacuation of its kind in which civilians were moved simply because of their race. "

110,000 Japanese were moved from their homes and sent to one if 10 camps, set up in make shift empty fair grounds, Coliseum and buildings. Tanforan and Topaz are the most known of the camps.

This is Okubos recording of what she saw, heard and experienced while evacuated to these camps. "To see what happens to people when reduced to one status and condition.", Okubo states. Cameras were not permitted, so she sketched, drew and painted what she saw. Every page has an illustration. Citizen 13660 is the story of her camp life.

Great book...Loved it!! -

In Citizen 13660, Mine Okubo documents her experience in Japanese internment camps. Told objectively, she illustrates how horrid and dehumanizing the living conditions were for Japanese citizens imprisoned in these camps. While her writing does not reflect how she personally felt about her experiences, the pictures tell a different story. When she writes about experiences like little access to drinkable water or being forced out of her home, she draws herself with a grimace or sorrowful eyes. Okubo's account is an important piece of American history that shows what happens when fear and prejudice grip a society. In the preface to the 1983 edition Okubo writes " I am often asked, why am I not bitter and could this happen again? I am a realist with a creative mind, interested in people, so my thoughts are constructive. I am not bitter. I hope that things can be learned from this tragic episode, for I believe it could happen again."

-

A nice, almost blase, look at the Japanese internment camps from a "resident artist."

I think the tone stems from the basic writing of someone who is primarily an artist, but I found it interesting that if the accompanying pictures had not been of sullen, slumped over figures, but rather images of happy-go-lucky folks, much of the text could have been used to make it a piece of pro-internment propaganda.

And actually, it was an admirable account of how the majority of Japanese conducted themselves in the camp...planting trees and building lakes to make the area more beautiful and forming their own governing bodies.

It does make mention of some of the agitators in the camp, but this isn't really explored.

A good, quick read. -

was surprised this was published in 1946 (and began as a project at Fortune magazine, like Let Us Now Praise Famous Men). Not exactly a graphic novel, not exactly an illustrated memoir. Okubo does some very subtle and funny and clever things with the juxtaposition of image and text, especially her own profile which frames and comments visually on each image, its expression often at odds with the first person "memories" in the text. is it easier to lie and elide with language than with pictures? is no one paying attention to a scruffy young woman's face, even on the page--does Okubo feel invisible making that face at that officer?

-

I'm interested in Japanese Americans during the 1940s. Citizen 13660 is an autobiography of a young Japanese American artist who was moved to a relocation camp at the beginning of World War II. She provides a sequence of beautiful mural type drawings to illustrate her book. The drawings add great detail to camp life. Gentle, compliant and humorous as they made this draining transition, I often wonder how their young men could be such fierce fighters for the U.S. In Europe during the same period. This is a small book that can be found on Abebooks.com . It is a little treasure.