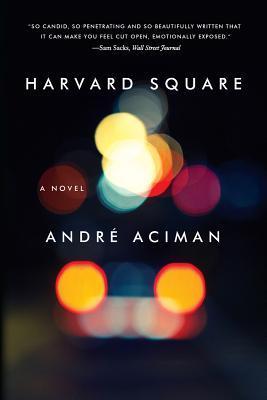

| Title | : | Harvard Square |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0393348288 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780393348286 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 304 |

| Publication | : | First published April 8, 2013 |

Now, with his third and most ambitious novel, Aciman delivers an elegant and powerful tale of the wages of assimilation—a moving story of an immigrant’s remembered youth and the nearly forgotten costs and sacrifices of becoming an American.

It’s the fall of 1977, and amid the lovely, leafy streets of Cambridge a young Harvard graduate student, a Jew from Egypt, longs more than anything to become an assimilated American and a professor of literature. He spends his days in a pleasant blur of seventeenth-century fiction, but when he meets a brash, charismatic Arab cab driver in a Harvard Square café, everything changes.

Nicknamed Kalashnikov—Kalaj for short—for his machine-gun vitriol, the cab driver roars into the student’s life with his denunciations of the American obsession with "all things jumbo and ersatz"—Twinkies, monster television sets, all-you-can-eat buffets—and his outrageous declarations on love and the art of seduction. The student finds it hard to resist his new friend’s magnetism, and before long he begins to neglect his studies and live a double life: one in the rarified world of Harvard, the other as an exile with Kalaj on the streets of Cambridge. Together they carouse the bars and cafés around Harvard Square, trade intimate accounts of their love affairs, argue about the American dream, and skinny-dip in Walden Pond. But as final exams loom and Kalaj has his license revoked and is threatened with deportation, the student faces the decision of his life: whether to cling to his dream of New World assimilation or risk it all to defend his Old World friend.

Harvard Square is a sexually charged and deeply American novel of identity and aspiration at odds. It is also an unforgettable, moving portrait of an unlikely friendship from one of the finest stylists of our time.

Harvard Square Reviews

-

(Originally reviewed June, 2014)

The Unredeemed Redeemer*

In your youth did you ever have an ostensible peer, a friend, who had an outsized impact on you, who seemed more than a peer or friend? Not someone you could marry or even hold onto; more of a force of nature? And not an ordinary mentor in your work or craft, but a life mentor?

This would be someone who could leave you with the hint of an idea as to how the belief in individuals with salvific capability arose.... Maybe somebody like that Kevin Costner role in The Big Chill, the one that ended up on the cutting room floor.

I did. Two, to be exact.

Being more prosaic, we could call them "social therapists:" individuals embedded out there who have an impact, but since there is nothing formal or regulated about their status, the effect can be unpredictable, even explosive.

But why be prosaic?

This book is set in the summer of '77, a sweltering summer past its midpoint. The protagonist, an immigrant himself and a graduate student in something like European literature, is existing on a miniscule budget. He's alone; summer-school students and fellow grad students are dispersed. He can go days without human contact. And he's failed his comprehensive exams. He has one more shot at passing. That is the context in which he encounters the unlikely salvific character.I was shifty, he was up-front. I never raised my voice; he was the loudest man on Harvard Square. I was cramped, cautious, diffident; he was reckless and brutal, a tinder box. He spoke his mind. Mine was a vault. He was in-your-face; I waited till your back was turned. He stood for nothing, took no prisoners, lambasted everyone. I tolerated everybody without loving a single one. He wore love on his sleeve; mine was buried layers deep, and even then... He was new to the States but had managed to speak to almost everyone in Cambridge; I'd been a graduate student for four years at Harvard but went entire days that summer without a soul to turn to. When he was upset or bored, he bristled, fidgeted, then he exploded; I was the picture of composure. He was absolute in all things; compromise was my name. Once he started there was no stopping him, whereas the slightest blush would stop me in my tracks. He could dump you and never think twice of it; I'd make up in no time, then spite you forever after. He could be cruel. I was seldom kind. Neither of us had any money, but there were days when I was far, far poorer than he. For him there was no shame in poverty; he had come from it. For me, shame had deep pockets, deeper even than identity itself, because it could take your life, your soul and bore its way in and turn you inside out like an old sock and expose you for who you'd finally turned into till you had nothing to show for yourself and couldn't stand a thing about yourself and made up for it by scorning everyone else. He was proud to know me, while, outside our tiny café society, I never wanted to be seen with him. He was a cabdriver; I was Ivy League. He was an Arab, I was a Jew. Otherwise we could have swapped roles in a second. pp. 51-52

Our protagonist is from Alexandria. His family left in the '60s when Nasser nationalized the businesses of the elite European and international class and made them foreigners while raising the natives up from the servant class. He saw his father broken. He is highly conflicted about a Mideastern Mediterranean world he's not sure he's ready to give up, but a world that doesn't exactly exist any longer. The world he aspires to is not his home but yet "the best that life had to offer." And he has an invitation. The significant friend is from Tunisia by way of Italy. His fate is foreshadowed from the first, but does not befall him before he has kickstarted our protagonist out of his doldrums, and not before a lot of revelatory words on the page.

This book was a seemingly mild yet powerful subterranean detonation awakening the feelings of a lost time period. Poignant.

But those particular characters in my life tended to be on a pedestal and not like this....I'd walked up to a stranger and found someone who, but for incidentals, could have been me, but a me without hope, without recourse, without future.

And I will say that, despite the friendship that blossoms, the protagonist denies his friend, maybe not three, but several, times before the inevitable end.

This is a novel that feels like a memoir. It seems real.

*What is "the unredeemed redeemer?" Well, the "redeemed redeemer" used to be seen by an earlier generation of Protestant bible scholars as a type or personage in "gnostic" thought. The redeemed redeemer was a sort of universal soul or over-soul imprisoned in the flesh, who, when he rose, would lift humanity with him. But being locked in the flesh, he, too, was in need of redemption. While ostensibly about a tradition external or alien to Christianity, that line of inquiry served to delineate orthodoxy as conceived at that time by those thinkers. That's the best I can do right now, based on what I'm getting out of Karen King's

What Is Gnosticism?--and I'll be tackling that review soon enough!

As for the unredeemed redeemer, I made that one up....

Addendum: Had the book club meeting on Harvard Square on Tuesday (Oct. 14, 2014). Nobody reacted just as I did, which although to be expected can still feel surprising. A number of people hated both the young men, who spent so much of their time chasing and catching women and then sitting in cafes talking about women. The lone male who was there got his (different) perspective in, though. Several people brought out the aspect of Harvard's historic atmosphere of eliteness and the intimidation factor for immigrants back then. The conversation also focused on the two guys' affinity based on their both being from Paris/French-oriented Mediterranean colonial cultures that no longer existed. If your world is gone, you will probably be attracted to any survivor who retains even a tiny piece of it. I was thinking again of Hannah Arendt and Heidegger, afterwards. ...I have had little tastes of that myself, once with someone who supposedly remembered me in my youth--one's youth, too, being a world that no longer exists. ...The oddest part of others' reactions to the book for me was that several saw the protagonist as unchanging. They thought he was always going to remain just the same, while for me the other immigrant was definitely a catalyst for the protagonist, and the summer of '77 the turning point of his life. Regardless, though, the discussion and preparing for it broadened and deepened my reaction to this book. -

The first time I read anything by André Aciman was

an essay called "On Loss and Regret," published in the Opinion section of The New York Times. I remember after a paragraph or two looking with startled curiosity at the name under the title again. Who is this man who writes with such clarity of matters of the mind and heart, and about how we deceive ourselves? Sometimes we ourselves do not even know what we think, but this man appears to see. Since that time--February 2013—I ordered several of his books, though I begin reading his work with his latest. It is fall and I live near Boston, and late summer-early fall days will always recall Harvard Square.

An early press release or an early review gave me the mistaken notion that this novel detailed a homosexual love affair. It is nothing of the sort. It is a love story between two men, but it is both less and greater than physical love. The two men see into one another's souls, like brothers. This story details a fleeting moment (the action takes place over a matter of months) in the lives of two very different, transplanted Middle Eastern men who are finding their separate ways in the rarified air of Cambridge, Boston. There is gladness and pain in the recognition of their differentness, for one salts the other and makes life vital and more interesting.”I was shifty. He was up-front. I never raised my voice; he was the loudest man on Harvard Square. I was cramped, cautious, diffident; he was reckless and brutal, a tinder box. He spoke his mind. Mine was a vault. He was in-your-face; I waited till your back was turned. He stood for nothing, took no prisoners, lambasted everyone. I tolerated everyone without loving a single one. He wore love on his sleeve; mine was buried layers deep, and even then…He was new to the States but had managed to speak with almost everyone in Cambridge; I’d been a graduate student for four years at Harvard but went entire days that summer without a soul to turn to. When he was upset or bored, he bristled, fidgeted, then he exploded; I was the picture of composure. He was absolute in all things; compromise was my name…He was a cabdriver; I was Ivy League. He was an Arab, I was a Jew…”

I admit to a long-standing curiosity about the mind of the Middle Eastern male, and this novel goes some way to reveal and explain that mind and character, insomuch as one or two men can be examples of their culture. This is fiction, but the motivations and rationales are as believable as nonfiction, which is all any reader can ask of a novelist. Almost every line carries an insight which propels us forward. Besides showing us the lonely, uncertain lives of recent immigrants, the smell and feel of a scholar’s life in Cambridge has a resonance that any student will recognize.

One morning I awoke to begin reading again, about two-thirds of the way through the novel. The spell I operated under while reading the previous night had been broken and my eyes and mind were back in assessment mode. I realized with a laugh that I was once again ‘listening’ to a capable man with scads of talent telling me who he slept with…what was it about me that invited these revelations? But my biting sarcasm soon passed and I was once again under Aciman’s spell.At Café Algiers he was almost always the first to arrive in the morning. Like Che Guevara, he’d appear wearing his beret, his pointed beard with the drooping mustache, and the cocksure swagger of someone who has just planted dynamite all over Cambridge and could wait to trigger the fuse, but not before coffee and a croissant. He didn’t like to speak in the morning. Café Algiers was his first stop, a transitional place where he’d step into the world as he’d known it all of his life and from which, after coffee, he’d merge and learn all over again how to take in this strange New World he’d managed to get himself shipped to. Sometimes, before even removing his jacket, he’d head behind the tiny counter, pick up a saucer, and help himself to one of the fresh croissants that had just been delivered that morning. He’d look up at Zeinab, brandish the croissant on a saucer, and give her a nod, signifying, I’m paying for it so don’t even think of not putting it on my check. She would nod back, meaning, I saw, I understood, I would have loved to, but the boss is here anyway, so no favors today. A few sharp shakes of his head meant, I never asked for favors, not now, not ever, so don’t pretend otherwise, I know your boss is here. She would shrug, I couldn’t care less what you think. One more questioning nod from Kalaj: When is coffee ready? Another shrug meant: I’ve only got two hands, you know. A return glance from him was clearly meant to mollify her: I know you work hard; I work hard too. Shrug. Bad morning? Very bad morning. Between them, and in good Middle Eastern fashion, no day was good.”

Before you begin reading, you might consider razoring out the Prologue and the Epilogue, which one might argue actually detract from the narrative since they are clumsy and feel tacked on. In Chapter 1, we immediately sense the mind and hands of the master.

__________________________

Clancy Martin

reviews the book in the NYT, May 2013. -

belki de aciman’ın bu romanında anlattığı şeylerin büyük bir kısmını son birkaç yıldır yaşadığım için çok bağlandım kitaba. ama çok bağlandım ya. ağlattı bile. keşke arkadaş olsaydık bile diyemiyorum, arkadaş olsak ikimiz de yabani yabani oturup sessizlikten rahatsız olurmuşuz, onu da anladım zira. ama keşke o anlatsa, ben de dinlesem. doyamıyorum.

-

What an extraordinary novel this is, even more ambitious than Call Me By Your Name. Whereas that novel dealt with an overtly gay relationship, Harvard Square delicately explores the intimate nuances of the evolution, and ultimate dissolution, of an unlikely male friendship.

The unnamed narrator is an Egyptian Jew and Harvard graduate student. He meets Kalaj, a Tunisian Muslim cabdriver, in a cafe one day, and is instantly drawn to his rhetoric and outgoing personality. The two could not be less alike: the narrator is diffident and bookish, while Kalaj is bombastic and outgoing. What they share is a sense of not belonging, steeped in homesickness, and a hankering for an idealized France. Both are outsiders, and therefore see in each other a kindred spirit.

Of course, Aciman runs the risk of alienating the reader and hardening his heart against a mouthpiece character like Kalaj (short for Kalashnikov), especially if he constantly rails against the iniquities of 'ersatz' America.

It is therefore an extraordinary achievement that the reader not only empathizes with Kalaj, but gradually begins to fall a little in love with his fallibility and dandyish outspokenness. Not for Aciman the traditional plot of having such a character gradually becoming radicalised and exacting a tragic and terrible revenge.

No, Aciman takes the much more tricky route of exploring the plight of the outsider in America, and how difficult assimilation can really be. There are no easy answers here, and Aciman is careful to show these characters warts-and-all. At the end of the day, Kalaj is rather unlikeable and frightening, while the narrator comes across occasionally as so gormless that the exasperated reader just wants to box his ears.

Aciman is a master of nostalgia and regret. Here he uses a framing device of the narrator bringing his own disinterested son to Harvard, and thinking back on his friendship with Kalaj, which paints the novel in a glowing and vaguely Spielbergian light. It is a risky strategy, as being too cloying could alienate the reader as much -- if not more so -- than coming across as too radical and West-bashing.

However, it works beautifully. The ending, in particular, is exquisite and heartbreaking, and inimitably so in the best Aciman fashion.

A lot of so-called 'political' novels are overly strident, and often make a point of wearing their hearts and colours on their book sleeves, so the reader is constantly reminded that what they are reading is An Important Statement. This is a particular temptation for authors dealing with the rather muddled and serio-comic politics of the Middle East region, where it is frighteningly easy to paint people black or white, without taking into account the myriad gradations of grey.

Harvard Square is a deeply affecting novel of outsiders trying to establish an identity and cultural roots in their chosen new homeland, but facing the consequences of entrenched xenophobia. It is a topical and highly relevant theme, and Aciman's humanity and compassion for his characters makes for an utterly exquisite and unforgettable reading experience. -

Longing pulses through all of Andre Aciman’s books — from his celebrated memoir, “Out of Egypt,” to his most recent novel, “Eight White Nights.” He’s a prose poet of confounding desires, an expert on Proust who ruminates on the scent of memories that haunt us.

His new novel, “Harvard Square,” opens with a prologue set in the present day as the narrator guides his unimpressed teenage son around the campus on a college visit. “Everything he sees,” Aciman writes, “seems steeped in a stagnant vat of nostalgia,” but the hallowed haunts that bore his son quickly draw the narrator into the past. And so the novel proper takes place in the hot summer of 1977, a fraught intermission that could have sent his life in a very different direction.

“Harvard Square” joins a long tradition of guilt-clouded stories about intense, unlikely friendships between men. In fact, Aciman initially seems to be revisiting the febrile atmosphere of his first novel, “Call Me by Your Name,” about a teenager’s obsession with an older student. But this time around, the narrator’s attraction is not sexual, and the object of his interest is more complex. This is not a tale of forbidden coupling but of forbidden rejection — an immigrant’s painful decision to assimilate into a culture that rewards reinvention.

We meet the young, unnamed narrator (who bears a striking resemblance to the author) during a crisis of confidence familiar to any mortal who has suffered the withering tedium of graduate school. Having failed his comprehensive exams, he’s trapped in Cambridge for the summer, tutoring French, working in the library and slashing through a long list of 17th-century books. An Egyptian Jew far from home, he’s worried — deeply worried — that he won’t pass the second time around: “Self-doubt scrapes down the soul, till all that’s left is a flimsy sheath as thin as a sliver of onion skin.” In his darkest, most rudderless moments, he realizes that “I was a fraud, that I was never cut out to be a teacher, much less a scholar, that I had been a bad investment from the get-go, that I was the black sheep, the rotten apple, the bad seed, that I’d be known as the imposter who’d hustled his way into Harvard and was let go in the nick of time.”

One day, in the slough of this despair, while sitting in a cafe, he overhears an obnoxious man talking in French like a jackhammer. He’s wearing a faded army fatigue jacket and jabbering like “Zorba the Greek on steroids.” Despite every urge to flee, the narrator feels so lonely, so desperate to speak French that he introduces himself. It’s a delightful encounter, re-created with the palpable sensation of a desperate thirst suddenly satisfied. Kalaj turns out to be a Muslim cabdriver from Tunis. “In no time,” Aciman writes, “we reinvented France with the very little we had that evening. Bread, butter, three wedges of Brie. . . . Cambridge was just a detail.”

Although they have nothing in common except their alien status, a friendship unfurls, filling the narrator’s life with color and drama. They meet again and again at this cafe in the center of America’s intellectual capital; they go on a double date to Walden Pond, the sacred shrine of self-

reliance. But they’re always hyper-aware of their otherness, their exclusion from the promise of the New World. The cabdriver’s overstated disdain for America and its ersatz culture is infectious. “I knew I was beginning to sound like Kalaj,” the narrator confesses. “By looking at him I was almost looking at myself. . . . He was just my destiny three steps ahead of me.”

Kalaj is outrageously flirtatious, almost comically seductive and eager to critique the narrator’s approach to women. “He was after passion, because he had so much of it to give,” the narrator says, “after hope, because he has so little left; after sex, because it evened the playing field between him and everyone else, because sex was his shortcut, his conduit, his way of finding humanity in an otherwise cold and lusterless world, a vagrant’s last trump card to get back into the family of man.”

This is a ruminative novel that will strike some readers as under-plotted. But “Harvard Square” is a plaintive love letter to displaced, wandering people, to anyone who longs for home and reaches unwisely for the hand of a fellow wanderer. “Maybe Kalaj and I were not so different after all,” the narrator reflects. “Everything about us was transient and provisional, as if history wasn’t done experimenting on us and couldn’t decide what to do next.” Aciman spins a hundred tragic, lush reflections on his fascination with Kalaj, but a less patient reader might wonder if a dozen such passages would have sufficed.

The story grows darker and more compelling, though, as the stakes rise and Kalaj’s attempts to secure a green card grow more panicky. Naturally, the immigration department is not so easily seduced by his “sputtering bravado,” precipitating a crisis that tests the limits of our narrator’s devotion. What really are the terms of their obsessive relationship? “Why had I ever befriended such a nut?” he wonders. And what, ultimately, is he willing to offer his uncouth friend, whom he regards with “a rush of love, loathing, and bile”?

In the end, it was only five months, a strange, long-forgotten episode that could have derailed the narrator’s life and frustrated his grasp for wealth and prestige. Only the sheen of these sentences, polished by tumbling in remorse for decades, show how deeply Kalaj affected him, how ashamed he still is. It’s an old story for Americans, but worth telling again when it’s told this well: Every act of immigration is also an act of betrayal. -

A Surprise, But Not the Good Kind – André Aciman’s “Harvard Square”

I had high expectations for André Aciman’s new novel “Harvard Square.” Friends spoke highly of an earlier novel of his. I enjoyed a recent essay by Aciman in the New York Times on “How Memoirists Mold the Truth.” He is a Proust scholar, from Egypt originally, and teaches comparative literature at City University in New York where he also directs the Writer’s Institute. With such rich personal history and expertise, I anticipated that “Harvard Square” would be a wonderful piece of writing.

It is not. I should rephrase. It is not a wonderful piece of writing, in my humble opinion.

Artistic appreciation is, to some extent, subjective. We all experience art in our own unique way. That individual reaction combined with the animated discussions when we disagree is what makes art so exciting and vital in our lives. A reviewer in the New York Times gave “Harvard Square” high marks describing it as “an existential adventure worthy of Kerouac.” So clearly, some people love the book.

But it seems to me that though there is a subjective component to artistic appreciation, when it comes to writing there are also more objective criteria that differentiate great writing from not-so-great writing. In my mind, “Harvard Square” fails on numerous of these criteria.

Firstly, we as readers are constantly being told what the narrator is thinking and feeling. Listening to a character’s internal dialogue can be a powerful story-telling tool when it is done subtlety and with nuance. But it’s off-putting when it is used obsessively and depicts the obvious and/or the predictable. I am more engaged as a reader in a piece of fiction when I have to surmise what a character is thinking and feeling by observing their actions and speech. As editors are fond of saying, “show me, don’t tell me.”

Secondly, the focus of much of “Harvard Square” is on a wild character called Kalaj who decries everything around him as “ersatz” meaning an inferior imitation. It’s one thing for a character to constantly repeat such an expression and quite another thing for the author of the story to use it ad nauseum not only from Kalaj’s mouth but also in the general narrative. I take it that Aciman’s intention in the novel is to depict the relationship between the narrator and Kalaj as ersatz in that the narrator is a pale and obsequious version of the vibrant Kalaj. But we as readers don’t have to be hit over the head constantly in order to discern this point.

Thirdly, Aciman in “Harvard Square” has a stylistic quirk of putting long series of questions one after the other into the narration. It is irritating and distracts from the dramatic flow.

I know that I’m being very judgmental and that there are more learned readers and writers who will disagree with my critique. But I had such high hopes as I approached the novel. My disappointment with “Harvard Square” is in large part because the writing style constantly interrupted my appreciation of a compelling story. That was a surprise, and not the good kind.

* * *

For information on André Aciman’s “Harvard Square”, see:

http://amzn.to/1bhSKlS

For information on my memoir “August Farewell” and my novel “Searching for Gilead”, see my website at

http://DavidGHallman.com -

“I hated almost every member of my department, from the chairman down to the secretary, including my fellow graduate students, hated their mannered pieties, their monastic devotion to their budding profession, their smarmy, patrician airs dressed down to look a touch grungy. I scorned them, but I didn’t want to be like them because I knew that part of me couldn’t, while another wanted nothing more than to be cut from the same cloth.”

A melancholic, nostalgic autobiographical novel about belonging and assimilation that focuses on immigrants finding their place in America in the 70s. It’s set amidst the privileged enclave of the most elite academic environment. A place filled with the most intelligent, the wealthiest, the preppiest, the best of the best, the elite. A place where one looks down on the commoners who will never be able to emulate or understand a Harvard graduate’s life.

At Café Algiers, an Egyptian graduate student at Harvard meets Kalaj, a Tunisian cab driver, struggling to keep his green card. They have one commonality: both come from Arab states in the Mediterranean. For the homesick graduate student he’s happy to speak French with fellow exiles. The café serves as a place to meet new friends. For the Tunisian, the café’s his home apart from his miserable marriage and his cab. [“He was proud to know me, while outside of our tiny café society, I never wanted to be seen with him. He was a cabdriver, I was Ivy League. He was an Arab, I was a Jew. Otherwise we could have swapped roles in a second.”] Over the next several months these two men will test friendship’s bonds.

Andre Aciman lovingly describes Harvard Square through minute sensory detail, various meeting spots—Café Algiers, Casablanca, Harvest, street names and students versus year-round inhabitants. The reader will feel like she’s walking around with him on every page. His Middle Eastern characters are rich with background. In Kalaj he creates an explosive and derisive character to play off the graduate student. Does the reader want him to get his green card or be kicked out of the United States forever? He’s rather a cad. A player. He seduces women and brags about his conquests in the café the next morning. Women cry about him. He’s been married several times. He complains about America while waxing nostalgic about the pristine beaches of his native Tunisia yet yearns for a green card. Merely for the money or does he have a darker motive? And why does a Harvard doctorate student become both enamored and disgusted with Kalaj?

As much as our graduate student feels he’s an Egyptian, he’s also becoming comfortable at Harvard. He wants to succeed and belong. While he enjoys this new scene he never knew existed at Café Algiers, he understands that his future belongs to academia and his Ivy League education. He’s nothing to feel ashamed about. -

A book that presented itself for what it was, an enjoyable 3 star book with a couple of interesting characters. I would call it an honest book not promising anything more than it is; a trip back to student academia with all of its self indulgences and passions mildly exaggerated. I would recommend it for good bedtime reading.

-

I've read a formidable list of literary fiction and writers writing about the loneliness of assimilation- the hunger for love and need for companionship, basic needs that everyone universally wishes for.

This is one of those well-written, yet slightly worn out tropes of friends who are trying to assimilate into American culture, and society. Our narrator is a PhD student at Harvard, studying literature, and falling in and out of love with women, wine, and fine cuisine. He's Egyptian- and yes, an outsider. He befriends Kalaj, a Tunisian cab driver with big dreams, a broken marriage, and the desire for a green card and The American Dream. Our Narrator wishes to fit within the social construct of bougie Harvard academia, but is drawn to his brash and big mouthed friend- whom he wants to keep secret, especially from Allison- a rich white girl. Kalaj finds himself in serious trouble and needs his friend's help from being deported- but at what cost?

The novel is beautifully written, with sensitively drawn out characters and Mr. Aciman is a master at writing about unrequited love or love that cannot be fulfilled, especially from his masterpiece of love and loss, "Call Me By Your Name". However, this book falls short in in its inability to free itself from cliche- whereas in "Call me by your name", he is able to write a masterpiece that has been written over and over again, simply due to the power of his language and romanticism. This left me feeling a little bit let down, since my last to forays into the world of Andre Aciman's world of the bourgeoisie had been books of about passion amidst the lives of the intellectual and privileged. This time, his language couldn't save some of the overly sentimental and familiar tropes found in "Harvard Square". A better book about fitting in as an outsider is Dinaw Mengestu's "The Beautiful Thing Heaven Bears"- and all the more sorrowful. -

Cambridge, Massachusetts – estate 1977

L'inaspettata amicizia tra due giovani mediorientali mette a confronto due differenti modalità di convivenza multiculturale.

Una tematica interessante nella misura in cui riflette uno dei problemi sociali che necessitano più urgenza di riflessione.

Come gestire la propria identità culturale in un contesto così lontano dalle proprie origini?

Da una parte la rabbia, il rifiuto e la critica al capitalismo occidentale.

Dall'altra il bisogno di 'inserimento, la necessità di essere riconosciuti, di appartenere.

Due uomini differenti per status e indole si rispecchiano e scoprono che:

"nessun essere umano è una cosa soltanto (...)ognuno di noi ha tante sfaccettature".

Nonostante l'interesse per la tematica, questa lettura per me ha presentato due falle.

Innanzitutto ad un certo punto il racconto si nasconde e si dilunga su bevute e scopate in cui si esplicita una filosofia di vita rasente alla misoginia. Ciò mi è risultato abbastanza antipatico.

In secondo luogo non ho apprezzato la morale che emerge. Aciman pare dire: "caro fratello fai come me se vuoi rimanere negli Usa devi meritartelo. Abbassa la testa, lecca culi, pugnala gli amici alle spalle e salva la tua carriera. Altrimenti torna al paesello dove vivrai felice e contento...".

Perchè questo è esattamente ciò che accade in "Harward Square".

[Tag personale: "No grazie!"] -

i chose this book because Aciman is the author of Call Me By Your Name and I loved the film. Harvard Square's pace is slow, which if you're like me, is not a bad thing. This is the story of friendship between two men, both immigrants, one from Egypt, the other from Tunisia, one a Jew, the other an Arab, one a PhD student at Harvard, the other a cab driver. The novel takes place in the summer of 1977. We see America through the bombastic Kalaj, who refers to everything as ersatz meaning inferior. It is the story of exile and the fear of losing one's green card. It is a love/hate relationship with America, its chicken wings, Walden Pond. It is also the story of a class system still in place, and of Harvard itself, of academics and comprehensive exam fear and staying up all late reading Chaucer. It is the story of relationships and the difficulties of intimacy and detachment and alienation. I expected the friendship between the two men to become romantic and in a way, it did, but very subtly. This is a charming and thoughtful novel. I already miss Kalaj.

-

《Alla fine è sempre la donna a scegliere, non viceversa, è sempre lei a fare la prima mossa.》

《Adoravo il suo corpo, adoravo quel sesso libero, selvaggio, egoista e privo di significato. 》 -

Two men from different backgrounds become instantaneous best friends only to have their friendship eaten away by various elements. The author uses the word 'ersatz' on about every page so that we will get that this is an 'ersatz' take on a relationship (it goes backwards, not forward: a substitute for our expectations from this kind of novel..get it...should I explain further?). Personally, I would have liked a more 'erudite' (fifth word in my dictionary after 'ersatz') take on the subject.

-

A powerfully evocative tale of a foundational friendship between two émigrés - one, a quiet Egyptian Jew studying at Harvard and the other, an explosive Berber cab driver - who meet at the Café Algiers in Harvard Square one hot summer in the late 1970s. Aciman deftly captures what is like to drown yourself in books and ideas, and open yourself to the world, in a collegiate environment, moving from one passion to the next as you get closer to the you you think you are. (In fact, the frame of the tale, the narrator's bringing his teenage son to visit Harvard and taking him on an unwanted tour through his old stomping grounds, shows us how profound this friendship and this summer was for the narrator.) This book reminded me a bit of Conrad's The Secret Sharer in that Kalaj, the cab driver, seems to be the narrator's mirror image, an old world id to his more assimilated super-ego. For a time, they function as inseparable soul mates, touring Harvard Square like it was their own private country, until they decide that they each must abandon the temporary home they've created and go their separate ways. Wonderful writing on friendship and regret, as well as self-discovery and awakening.

-

I started this before I left for school in the fall last year, and got so distracted that I didn’t really pick it up until yesterday. I only had about 100ish pages left so finishing it was not difficult, but it was sad to say goodbye to a story that I was engrossed in about a year ago and fell right back into yesterday and today.

I suggest Andre Aciman to all who haven’t read him before. Though this isn’t my favorite of his books I loved it and fell in love with the characters with all of their deep flaws and passions. A great read! -

Having only read “Call Me By Your Name” and “Harvard Square” by Andre Aciman, I prefer Harvard Square. While Harvard Square is not explicitly Queer in a lot of ways, it does deal with the same themes of longing, desire, and feeling so genuinely connected to somebody that appear in Call Me By Your Name.

On paper, Harvard Square is a relatively simple story: a young, Jewish, grad student from Egypt meets an Arab taxi driver. The main conflict of the book is the grad student feeling like an outside compared to the rest of Harvard. He (the narrator does not have a name) is both enthralled and terrified of Kalaj because Kalaj reminds him of himself in a lot of ways: immigrated to America, an outsider, living life on the fringes of society.

My favorite thing about Harvard Square is how slow and romantic the book is. The details of Harvard, dark coffee shops, summer days, are exquisite. A lot of the narrator’s thoughts on identity, feeling comfortable in one’s own skin, and conformity are very poignant. -

Ugh, first I waited too long to review (flu and too much work), and then Goodreads ate my review. So now what?

I can sum up my problems with this book rather succinctly: While Kalaj, the compelling, charming, abrasive, manipulative and ultimately self-destructive foil for our narrator is well drawn, the narrator himself is a big blank - an empty and not very convincing shell. That lack gives the book a hollow core.

And then the book just meanders - I wondered about Aciman's self-editing on this one (I loved Out of Egypt and Call Me By Your Name)-- things just seemed inconsistent and sloppy. The time line doesn't work - the book begins in July-ish and ends before Christmas, but even before the semester starts, the weather is described as "Indian summer". Love affairs, including plans for marriage and meetings with parents, seem to come and go with in the space of weeks - much will be described as having happened, but chronologically, no time will have passed. People don't see each other for weeks, then they do, then they don't, and again - no chronological time has passed. People are described as "always" doing something, but then the timeline makes clear that that new found habit can only be of a few days duration. Other inconsistencies abound.

I see from the Internets that Aciman is firmly associated with Proust (in his own mind?), and perhaps that's the excuse for all of this imprecision - it's the nature of memory, of course, the love affair seems like it lasted years, but that's our middle-aged memory of youthful passion. But Aciman is not Proust, or he hasn't earned our patience in the same way, at a minimum, and so this is not great art, but merely annoying.

Also, there were a few anachronisms - one that I noticed in particular was people stepping outside to smoke during a movie in 1977. I can't say for sure, but I remember smoking in movie theaters being legal in the late 1980s, so seems off. -

So, a Jew walks into an Arab cafe. This sounds like the lead in for a bad joke but it is rather the opening of a remarkable new novel, Harvard Square, by Andre Aciman. The Jew is a Harvard graduate student from Alexandria, Egypt. He is a diffident student in a strange land, shy, intelligent and well prepared to make his mark in America. The Arab is "Kalaj," a Tunisian immigrant, uneasy in his new home and scathingly critical of everything in "ersatz" America. He is voluble (his nickname is short for Kalashnikov, coined for his rat-a-tat speech), opinionated and for our nameless narrator, utterly charming. They become the best of friends despite the huge separation between them. Kalaj squires his friend through Harvard's night life, introducing him to vices, virtues and a procession of young women taken with the larger than life personality of the Tunisian taxi driver. Kalaj is in the midst of a divorce from his American wife, a situation that severely endangers his chances for a green card. The narrator has a green card, that magic ticket to America but is in danger of failing, once again, his comprehensive exams and thus, his dissertation.

Author Aciman, from Alexandria and now a professor of comparative literature at CUNY, has previously written essays on the problems of identity and displacement and in this novel vividly illustrates differing aspects of this from the diverse perspectives of his characters. Although the novel is set in the Harvard Square of the late 1970s the problems and indeed much of the geography are familiar. As an immigrant navigating Cambridge and Harvard Square in the 1990s I have resonant feelings for the protagonists and fond memories of the many cafes frequented throughout the book. Professor Aciman is clearly also familiar with the peculiarities of academic life and although this is not a "campus novel" per se it does engage in some pointed satire at certain types of academic personalities and institutions. -

2.5 perhaps. André Aciman’s

Eight White Nights is a tough act to follow. In that novel, Aciman did such a wonderful job of keeping the reader’s interest in a ridiculous obsessive relationship (all obsessive relationships look ridiculous from the outside, I suppose). It was one of those perfect little novels, and I look forward to reading it again.

Sadly, Harvard Square does not come close. It’s well written, and the second half is far better than the first. But despite the always intriguing theme of fitting in (and not) in a foreign country, and what could have been just as fascinating a relationship (between male friends), the novel didn’t work, at least for me. Everything seemed wrong somehow, from the terrible title, to the relationships, the frame, the time sequencing, the voice, the lack of what another reviewer refers to as "the layers," even the pain. Aciman showed that he could pull a miracle off with annoying characters, but lightning didn’t strike twice for him. -

Curious and courageous readers will ride in the back, front, and jump seats of this volume's steel-toed Checker Cab. The dangerous jump seats are the author's offer for the safest ride.

Readers who are fully alert-and-oriented to name, date, place, and purpose of visit will ably celebrate the rich regret and dashed hope evoked by Harvard Square: A Novel. Its participial past, present, and future drill and fill holes in heads and hearts.

In hurricanes of once distant memories stirred by this masterpiece of coiled concision, missed boats are irreparably crashing against rocks. Long overdue wellness checks will, won't, or can't happen.

Context for the glare of here and now is conjured by embers of there and then. Faces and places of our private known and unknowable likes and loves are validated by this author's victory.

Novelists of this level of mastery are neurosurgeons. Without reservation, I recommend this pen's precision. -

An Arab and a Jew became friends, or did they? After finishing Call Me By Your Name in less than a day, falling in love with Aciman's dreamy, atmospheric prose, I just had to read more from him, but I wasn't quite as enamored this time around. Harvard Square is an enjoyable read for the most part, providing an excellent insight into the life of wanderers in a strange land, with two characters who not only juxtapose each other, but see themselves in one another, but it was a bit of a drag at times.

I wasn't a fan of the blatant misogyny of the two characters, but I've forgiven other books for far worse. Reading about two heterosexual, downright unappealing men bond over the women they've slept with and the subsequent degradation of them, at times, was tiresome. That being said, this book was still a decent read. I enjoyed the complexity of the friendship between the unnamed narrator and brash cab driver Kalaj and, of course, Aciman's writing style never ceases to hook me. -

André Aciman is a poet of exile, a chronicler of displacement and its discontents.

Born in 1951 in Alexandria, Egypt to Jewish parents with roots in Turkey and Italy, he and his family were expelled from Egypt by the Arab nationalist regime. When he was 15, the Acimans moved to Italy and four years later to New York.

His first book, the memoir Out of Egypt, was published in 1995 to enthusiastic reviews. Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times compared him to Lawrence Durrell, the British author of The Alexandria Quartet. The critical praise. . .

Click to read complete

book review of Harvard Square by André Aciman at New York Journal of books -

DNF. i skipped all the way to the epilogue from chapter 4 just to get a glimpse of the resolution but still, i'd give it 0 starts if i could. the writing, although spectacular because what else is there to expect from aciman, could not overshadow the clear sexism depicted throughout the novel. this book treated women like second-class citizens and starred a typical misogynist who took another one in the making under his wing. the only reason any woman should read this book, is if you wanted to know the exact type of men you should avoid in society.

-

I fell in love with André after reading Call Me By Your Name and this novel did not disappoint.

This is basically a story of two very different men that are both immigrants and don’t know where their lives are heading. They both have their own problems, not just financially and spiritually but they’re also dealing with their own demons. It took me to a Harvard I’ve never experienced but it’s almost as if I did in real life throughout this novel. -

Didn't finish. made it halfway through and just found it unbearable. it was just rather boring

-

Just couldn't get into this which was a shame as I loved Call Me By You Name :( I didn't finish because the language was too clunky for me. I couldn't get into the flow with this at all.

-

3.5 (rounded up to 4) stars.

A nice book, a simple one, yet complex in feelings; not too deep (as are Aciman’s characters), yet with many angles and aristas.

However, this was a book that didn’t touch me too much. What did I expect to find in this book? I don’t know, but I would’ve loved to know why he became friends with Kalaj, why he wanted him out of his life in the end, what his true feelings were...

I’ll leave it on hold, but I might visit it once more in the future. -

Een boek over de vriendschap tussen een jonge student ( van Joodse afkomst uit Egypte) en een charismatische taxichauffeur (van Tunesische afkomst).

Vriendschap kan mooi en waardevol zijn, maar soms ook een blok aan je been ... of beide tegelijk. -

A complicated story about friendship 🥺 and literature and café culture and the end made me so emotional & also nostalgic for Dartmouth

I forget that there reviews are public and not a blog -

I received a copy of this book through First Reads.

Strengths:

-Powerfully portrays the alienation and confusion that permeates any college student's life, but especially that which characterizes the foreign-born college student's life.

-One is drawn into the narrator's interior battle between remaining loyal to a relaxed, Meditteranean-style approach to life and choosing to give in to the pull of the frantic, American "ersatz" lifestyle. As is probably the case amongst many immigrants, the narrator very much has a love/hate relationship with America; while America has given the narrator a great chance to succeed in life and better his place in the world, American culture and people are oftentimes repellant. This creates great frustration.

-While I have never been to Harvard, I feel that this book probably paints a pretty accurate picture of the pettiness and haughtiness that is common to people in that bubbled environment.

Weaknesses:

-I fail to grasp the true significance of the narrator's best friend Kalaj. The author hints at various points that Kalaj is supposed to be some sort of "double" for the narrator; Kalaj is supposed to embody what the narrator would end up like if things didn't turn out well for him in life. One cannot really grasp how this makes sense. While the narrator is relatively quiet, introspective, and book-smart, Kalaj is brash, a womanizer, street-smart, and always getting into trouble. It just seems like they have two somewhat different personalities, not that one is necessarily better than the other. In addition, the relationship between the narrator and Kalaj is certainly strange. The narrator alternates between hating and loving Kalaj, sometimes for reasons that make sense and other times it just seems like the narrator is being fickle. Anyways, so while the relationship between the narrator and Kalaj is supposed to be the focal point of the story, to me it wasn't all that compelling.

-While I know that this book is more of a character study than anything else, it did need some more action interspersed in order to move things along. The book definitely dragged at points.

Overall, it is an OK read.