| Title | : | Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 309 |

| Publication | : | First published March 20, 1997 |

In an attempt to discover why, Haruki Murakami, internationally acclaimed author of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and arguably Japan’s most important contemporary novelist, talked to the people who lived through the catastrophe—from a Subway Authority employee with survivor guilt, to a fashion salesman with more venom for the media than for the perpetrators, to a young cult member who vehemently condemns the attack though he has not quit Aum. Through these and many other voices, Murakami exposes intriguing aspects of the Japanese psyche. And as he discerns the fundamental issues leading to the attack, we achieve a clear vision of an event that could occur anytime, anywhere. Hauntingly compelling and inescapably important, Underground is a powerful work of journalistic literature from one of the world’s most perceptive writers.

Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche Reviews

-

Potent oral history (with some incisive commentary) by Murakami on the Sarin Gas attack in the Tokyo subway - 34 commuters detail their experiences, with much of the shock focusing on the mundane (a man still buying milk after he's badly poisoned). There's a metronomic beauty to the repetition of this section, which makes it such a shame that this version is severely abridged from the Japanese, which has twice the number of victims. The book then makes a remarkable pivot and treats members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult w/ the same focus and care. Here there are forced LSD trips, ECT shocks, and many other horrors, but the two sides end up forming a dynamic, frightening whole.

-

Absolutely heartbreaking. I had no idea about this event in history until reading this. Insane.

-

On March 20, 1995, during the morning rush hour, five men dropped 11 bags of sarin on five subway trains in Tokyo. They punctured the plastic bags with the sharpened ends of umbrellas and exited the cars as the deadly liquid leaked onto the floor and evaporated into the air of the crowded trains. In the end, 13 people were killed and 6,300 more were injured, many of them left blind or paralyzed. Japan was flung into crisis mode.

The men who caused the havoc were members of Aum Shinrikyo, a Japanese quasi-Buddhist cult led by a former acupuncturist called Shoko Asahara. They hoped to bring about the apocalypse. At its height, the cult claimed more than 50,000 members (tens of thousands of them in Russia) and presided over a vast pool of funds, at one point claiming to control more than a billion dollars.

It's been 20 years since the Tokyo subway attacks. Asahara and the other major planners of the attack sit on death row. Its chemical weapons laboratories have been shuttered. But where Aum failed in its mission to bring about a global apocalypse, it succeeded in leaving a dark bruise on Japanese society, one that still aches over two decades later.

All this expertise came in handy when Asahara wanted to build an arsenal fit for a supervillain. In a gated community on Mount Fuji, Aum's biochemists engineered boatloads of chemical and biological weapons, from anthrax to weaponized Ebola. A weapons factory nearby produced AK-47 parts. In 1994 the group purchased a twin-turbine Mi-17 helicopter from Azerbaijan for $700,000, according to reporting done by Andrew Marshall and David Kaplan for their bookThe Cult at the End of the World: The Terrifying Story of the Aum Doomsday Cult, from the Subways of Tokyo to the Nuclear Arsenals of Russia. Before Aum dug its own grave with the Tokyo gas attacks, the cultists were getting terrifyingly close to obtaining a nuclear bomb. It is no wonder that Japan has been so deeply scarred by the group—they were petrifying.

Japan was utterly bewildered that young, educated people would give up everything and devote themselves to such a deranged organization. Aum is actually still in existence albeit in two offshoots - Hikari no Wa, which means "Circle of Light," was started by a former higher-up of Aum as a splinter group. Aleph is the original cult, just with a different name.

Haruki Murakami is my favourite author. I just love his writing style and surreal novels. This, however, is a little different - it's non-fiction for starters. I enjoyed reading this as much as his other books and I don't think it could have been as great a history book if it had been written by a different writer. Japanese authors seem to appeal to me in a way that no others can, I can't quite put my finger on exactly why this is but i'm not complaining!

In this book, Murakami interviews the victims of the attack in order to try and establish precisely what happened that fateful day on the subway. He also interviews members and ex-members of the doomsdays cult responsible, in the hope that they might be able to explain the reason for the attack and how it was that their guru instilled such devotion in his followers.

In spite of the perpetrators' intentions, the Tokyo gas attack left only twelve people dead, but thousands were injured and many suffered serious after-effects.

The fact that people are still suffering - not only the physical consequences but the suffering caused by a constant fear of something like this happening again a bit like the threat of attacks the West are experiencing from radical Islam, shows that such a momentous and horrific event never ceases to be on the mind of citizens. Just like in the West, Japanese political leaders are requesting more surveillance powers and are using the Aum affair to further their agenda.

The Tokyo subway gassing remains the most serious terrorist attack in modern Japanese history and in many ways the Aum Affair is an open wound in Japan. It really is a heartbreaking event from recent history that will be forever remembered in Japan, when the wounds will heal is a question no-one can answer.

Kids attending college now in Japan would have only been two or three during the Aum Affair. It will eventually fade into history and new series of crises will take its place. But for now, nearly 23 years on, the macabre mania of the cult still resonates. -

"without a proper ego nobody can create a personal narrative, any more than you can drive a car without an engine, or cast a shadow without a real physical object. But once you've consigned your ego to someone else, where on earth do you go from there?"

-- Haruki Murakami, Underground

Looking back 20 years to the Tokyo Gas Attack, it seems inevitable that Murakami would write about it. Writing about dark tunnels that bridge both the victims and the devout, that link a damp tongue of evil with the milk of everyday kindness seems a natural space for Murakami.

This isn't a perfect look at Japanese Death Cults or even the Sarin Subway Attack of 1995. It is basically a series of interviews. First with the victims of the attack, the survivors, the families, the doctors and scientists. The few who would actually talk about it. That was part of the purpose of this book. Japanese culture was quiet about the attack. The government would prefer to move past mistakes. The survivors too just wanted to move past their second victimization. The Japanese Psyche is an area that interested Murakami and he seemed to feel a need to explore the wounds that festered in Japan after the attack (and the Kobe quake). He felt a need to let the harmed speak; to give voice to silent; to clear the air. He wanted to return to his country and shine a light into the dark tunnels that many there wanted to seal off forever.

After interviewing a few of the victims (most of the hundreds of victims didn't want to talk about it, and only a few dozen were willing to be interviewed, even with Murakami's VERY liberal interview process), and after Underground was first published, Murakami wanted to get a better sense of those members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult. So, he added a section. He might not get to interview those who actually perpetrated the Sarin gas attack, but he could speak to their brothers and sisters. He could use those same techniques to explore what drew these young, intelligent seekers into a cult that would perpetrate such a heinous attack. He did it with very little pre-judgement. Those he interviewed from Aum covered the track of belief. Some had left. Many had moved on into smaller pods, surviving the best they could. Some struggled inside belief. Some struggled outside of belief, now empty of their faith, but unable to return to any form of normalcy.

In many way the book reminded me of both Jon Krakauer's

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith and Lawrence Wright's

Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief. Murakami's book was less formal, less direct, and not quite as sharp as Krakauer or Wright's books. He let his subjects speak and thus the story would always remain unfocused a bit. His book's structural limitations let you sympathize with both groups, but there was very little mapping to the narrative.

It was a good book, just not a great book. It was interesting, just not fascinating. I'm glad I read it more because it was a Murakami book and less because it was a great book about cults or terrorism. It was a check mark. It was a pin on a map. It alone, however, wasn't a destination. -

In 1995, some members of the Japanese religious cult Aum have released toxic gas in the Tokyo underground system. While there were relatively "few" deaths, the survivors have all been left with horrible mental and physical scars in the aftermath.

The first part of the book contains interviews with the victims and their families, while the second one (published a year later) is made up of interviews with current and previous Aum members.

When I started reading it, I had absolutely no idea what the book would be about. Having previously read and loved

Norwegian Wood and

Kafka on the Shore, I figured I had a high chance of liking just about any book written by Murakami. Yes, I've always been excellent at jumping to (all the wrong) conclusions.

At the time I was reading this, I was in the middle of my notice period: stressed, overworked and just plain miserable. Don't know about you, but I can never sit through an exit interview without some serious waterworks being involved. Professional to the last second, I know.

Anyway as I was saying, reading the accounts of the Sarin victims who stubbornly dragged themselves to work despite being in terrible condition, made me feel even worse about my constant complaints. Not that it changed my behavior, or make me feel better about my workload. I just love victimizing myself way too much. Still, it definitely gave me a different perspective.

The stories of the victims have left a lasting impression on me. Nevertheless, there were too many of them. I realize that this sounds incredibly heartless, but after a while, the accounts all started to sound the same. That is not to say that it lessened any of the horrifying events. I can still recall the terrifying mental images, that the accounts of the family of the shop assistant left in a coma brought forth.

That said, I found the second part much more interesting in comparison. I wouldn't go as far as saying that I LIKED reading it. A lot of the remaining members are still unconvinced about the truth regarding the atrocities of the terrorist attack. But it was a definite eye-opener, seeing the type of people who would join Aum, and their reasons for continuing to stick to their beliefs even after all the bad media coverage.

Score: 4/5 stars

This was an extremely moving book, which I'll definitely remember for a long time. -

Videorecensione:

https://youtu.be/PzZ_u1UjWk4 -

Murakami’s partial attempt to explain why people joined Aum left me dissatisfied. Could it really be that some people want someone to watch over them and spare them the anxiety of confronting life situations on their own? A one way ticket delivering them from the need to ever have to think for themselves? He writes that we can’t fault people’s sincere attempts to find answers. Agreed. Does this mean that in one’s search they leave critical thinking behind? In one of the interviews he held a member remarked that it is spiritually immature to be angry. I guess that means I must be spiritually immature. I definitely felt anger towards those that released sarin gas on innocent men, women and children. For what? This is never explained. In another interview a member reasoned that killing someone would be acceptable once you were initiated into the highest level - some distorted version of Vajrayana. This affords one, per this man, to fully grasp transmigration of souls. Somehow this makes murder okay. To achieve the higher levels of consciousness the leaders subjected initiates to shock treatments, sleep deprivation, verbal abuse, massive doses of LSD, extreme heat, blindfolds, isolation, inadequate nutrition and something they called the Christ initiation. I can imagine these folks would believe they saw their false prophet levitating after taking that much lsd. Beware those that claim there is only one true way. The interviews with those on the subways when the sarin gas was released became repetitive. I found myself losing track or more accurately resorting to going numb with the horror of it all. The second half when the cult members are interviewed was an improvement as here Murakami at times manages to dig in and ask some pointed questions. I understand this was not his intention but I feel the book would have benefited from some analysis. I was left with many questions which will need to be answered elsewhere. Then again I’m not likely to ever fully comprehend voluntarily joining a cult let alone a doomsday cult.

-

There was a terrorist attack in the Tokyo subway system carried out in 1995 by a religious cult called Aum. They released poison gas, called sarin, during rush hour on several different train lines, killing 13 people, and injuring hundreds of others.

This book contains interviews of people caught in the attack, as well as interviews of members of the Aum cult, although none of them were perpetrators of the attack.

As a reader from another country, I feel like I'm missing a lot. I read the book feeling like Murakami was assuming I already was familiar with both the gas attack, and the Aum group, and I'm not, so I was having to piece together a picture from the narratives, and I still don't think I have the whole story.

Also supposedly, it's a book about the Japanese psyche, and again, I felt like I was missing that background knowledge a Japanese reader would have. So, I'm having to infer a lot out of the interviews. Maybe that's the whole point. Murakami wants us to draw our own conclusions.

The picture I got was of people so dedicated to their work, so much seeing themselves as not individuals, but as workers in a larger community, that they tried to carry on, no matter that they weren't feeling well. If they can just hang on until the next stop, they'll be able to get off the train and go to work. Very few of them complained about the weird smell, or having trouble seeing, or even breathing. They themselves were not that important. Again, this was all unspoken, but just what I'm concluding from how the people behaved as reported in the interviews. I don't know how unusual people were behaving on the day of the attack, compared to any other day.

Murakami doesn't draw many conclusions, and he doesn't bring in any experts to explain how or why people behaved the way they did on the day of the gas attack. Sure, I can make some inferences, but I don't know how fair they are, given that we're only seeing the reports of people willing to talk to a reporter.

After the first section, which concentrated solely on victims of the attact, came the interviews with members of the Aum group. The contrast was fascinating. Compared to the first group, who didn't have much sense of themselves as individuals, everyone who Murakami talked to from Aum seemed preoccupied about the Self, what is the true Self. I got the sense that in Japan, people are not encouraged much to be themselves. Not like here! In Aum, there was special training to uncover that hidden Self, or possibly to eradicate it completely in service to the leader. I'm not entirely sure, and I don't think the Aum were, either.

The other attraction of the Aum group was getting to renounce all ties to the world, and how freeing that was to those in the group. Again, the underlying message seemed to be how high pressure and stressful the world must be for those living in Japan's consumerist society, but it was never stated outright.

So, don't read this book looking for answers as to why the Aum conducted the terror attack, or for a general overview of Japanese culture. Perhaps in a future edition, the publishers could include an introduction about the attacks for readers from other countries. I liked this book a lot, I just wanted more. -

I had to learn more about the Japanese as a form of consciousness. - Haruki Murakami

I've always known Murakami for his mystical, mythical stories. Following his characters is usually like taking dancing classes: the first steps seem quite sensible but soon you find yourself in an inextricable knot that you don't know how to get out of. His stories are from another realm, to such an extent that Murakami himself seemed way out there. I always pictured him as a black-clad dreamweaver, spinning his magic machine in a jazzbar attic with only cats for company, on a remote island somewhere on the other side of the world.

Not so in Underground. Before leaving his abode to talk to the common people, the magician has taken off his robe and wizard hat and left his wand on his bedside table. To talk with real people and get their real stories. This book is non-fiction, but sometimes I found myself hoping that through this narrative a touch of magic could make it all seem a bit more light and distant. The contrary happened, and the remote island that is Japan might as well be the isles of Great Britain for how close this piece of investigative journalism has brought this special country to the shores of my mind.

As you probably gathered from the blurb, this book is about the gas attacks that took place in the Tokyo subway system, on a beautiful day of spring in March 1995. A religious cult, Aum Shinrikyo also known as the "Doomsday cult", released packets of sarin gas, leaving many dead, many more injured and an entire country in shock. Murakami, in an effort to get to know his fellow countrymen better through the lens of this heinous aggression, undertook interviews pertaining to these attacks with survivors, relatives of the deceased, medical personnel and members of the Doomsday cult.

This book consists of three main parts, the first being "Underground" the way it was originally published: the testimonies of victims and their relatives. The second part is a short essay by Murakami in which he tries to distill some lessons. The third section wasn't originally part of this book and is titled "The Place that Was Promised", containing interviews with (ex-)members of Aum Shinrikyo.

Part 1: The victims

The interviews are organised according to which train line the interviewees were on, each "train line" track introduced by the movements of the perpetrators of the gas attack. The interviews conducted with the victims are all structured in the same way. First you get a short, basic profile of the interviewee, usually consisting of his or her job, family situation and sometimes a little detail like whether or not they like sake or have a special character quirk. Despite these short introductions, the people having been interviewed seldom felt like real people to me. This is in part due to the structure and in part due to the interviewees reticence to speak up.

After the introduction, the victims first talk about their daily morning routine: what time they get up, what trains they take, what job is expected of them. What this has taught me is that most people in Japan, or at least all of the people in this part of the book, are extremely duty conscious. Work is important. Work is life. 24-hour shifts, where employees sleep over on their job, are nothing out of the ordinary. Commuting for two hours or more to get to work and to only get back home again when the kids are all asleep is part of life. This part of the interview's structure is rather dry and factual, not to mention extremely repetitive. Apart from an endless enumeration of train schedules the only thing I remember is one guy waking up every day at 5 o'clock in the morning to water his huge collection of bonsai trees.

Second, the interviewees talk about the gas attack itself. Where were they at the time? When did they notice things went wrong? What symptoms did they have? What did they do? This part of the interview, despite the shocking nature of the gas attack itself, is also quite dull due to all the repetition. The same symptoms of eyes tearing up, narrowed pupils resulting in a darkened vision, breathing problems and coughing fits are mentioned again and again. And again. This repetition does come with the (perhaps intended) effect of making the immediate effects of the gas attack indelible from the mind. Wet newspapers, mops, a PA-system filled with panic are but a few of the images that will stay with me.

What was most notable though, was the self-effacing nature of these commuters. They show a lot of modesty when relating their suffering. Even when faced with the quite unusual symptoms of sarin entering the body, most people tried to carry on with their daily routine. They needed to get to work. They couldn't be late. They'd have some explaining to do if that report wasn't finished. One guy, almost blinded and choking, actually went ahead and bought a bottle of milk before going to the hospital. He bought milk every second day and the day of the gas attack was a second day so what else could be expected of him? In the midst of the gas attack most victims seemed more worried about what others would think of their behavior rather than their own health. They doubted their own judgment. And almost nobody would speak up. People would start coughing and collapsing, yet the power of routine prevailed. Until reality finally caught up with them and saved most of these peoples' lives.

I haven't lived through an attack like this so I hesitate to call that reaction strange, but the reaction did help matters, since most people stayed remarkably calm during these gas attacks. There were no outbursts of panic, no stampedes of people. The commuters formed orderly lines to get out of the station. A lot of this naturally had to do with people having no clue what was going on, thinking the victims who collapsed were individual cases and their own symptoms being those of a flu or a common cold.

The third part of the interview structure is about the after-effects of this attack. How did it affect the victims' health, work, personal relations? The first interviews are very silent on that, due to the disinclination of the interviewees to share too much personal information and due to the respect Murakami shows for that sentiment. This adds to the impression that these people feel less real somehow, less identifiable. One man filed for divorce the day after the attack after having seen the lukewarm temperature of his wife's response. Some people had trouble performing well at work, due to loss of energy and concentration. Most of the time they were treated well by their employers, but a part of me thinks it's only these stories that made it to the book. The modesty in suffering and the respect for employers and work bosses seems too great to allow publication of anything critical in this book.

At the end of each interview the people are asked about their stance towards the cult and the perpetrators. These reactions range from anger and hatred, demands for the death penalty (didn't realize they still did that in Japan before this book), to a gentle understanding and acceptance of the facts, with a strong will to move on and get back to routine.

Overall, I'd say this entire part could and maybe should have been stronger. Murakami showed a lot of respect for the victims, which is very understandable from a human point of view but leads to less immersive results in a book. He didn't tease them out of their cages and in the end the overall image is the same one gets of people you share a subway train with: anonymous, bland, interchangeable. Two testimonies, the one with the brother of a victim who slipped into a coma and Murakami's telling of meeting this woman after she woke up with severe impediments, were the strongest parts of this book. Maybe the "sensationalist" side is part of that since this is one of the most dramatic testimonies, which would be a shameful argument from my behalf, so I like to think it's because more backstory is offered to the people involved. The same goes for the story told by relatives of a victim who died. These gripping parts made me regret the interviews weren't conducted (or repeated) at a later stage, because none of the testimonies come with a certain sense of resolution or ending. You're left wondering what happened to these people afterwards, like whether or not that one woman got to go to Disneyland. But that comes with non-fiction, obviously, and my wonderment is testimony of Murakami occasionally allowing his readers to truly feel connected with the people he interviewed.

Part II: Essay

I don't have much to say on this, meaning it was rather underwhelming for me. It does show the human side of Murakami, a stranger in his own land. In the essay he also shows some linkages between this book and his works of fiction, most notably Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. At first I thought HBWatEotW (sorry about that) was based on the Disneyland testimony, that deals with a person forced to live locked inside her own head. But his work of fiction predated these interviews, making the links even more mysterious. The links are there and intriguing to read up on for any Murakami fan.

Part III: The Cultists

Let me first emphasize that the cultists in the interviews were not actively involved in the gas attacks. Aum Shinrikyo was a huge community and not everyone knew everything. Because this book started with the tale of the victims and the people helping them, the "Good"-part, it's almost natural for a reader to approach this part as the one of the "bad guys". But again, this is non-fiction, not Lord of the Rings, and the distinction between what is good and bad is not easy to make.

A distinction that is easier to make is interesting and not interesting. These interviews were vastly more interesting, because Murakami acted more like a critical interviewer here. There was no fixed structure, and he dared to question what his interviewees said, resulting in inspired dialogues on societal values, a struggle for a sense of belonging and purpose, and what the life in a cult looks like. The testimonies were all gripping, the people felt like real people with interesting stories to tell. This gives the reader, especially those that stepped in with the idea that these are the "bad guys", the conflicting feeling of being able to relate better with them rather than with the victims.

The people who decided to join the cult are a bit special, but not so special that you couldn't be one of them, that you couldn't relate. I certainly could. You read about people with artistic aspirations, or deeply scientific ones, with philosophical questions that have no place in a business-minded society. Some people, like doubtlessly many here on Goodreads, turn to literature and find answers there. Most of the cultists also started that way, getting their hands on books published by the cult and being inspired. They didn't feel like they belonged in society and thought to have found their home in the doomsday cult. Who doesn't sometimes feel out of place? Who doesn't, on their daily commute to work, sometimes wonder if they're not throwing away a little bit of their life every day?

And that's where this book truly got interesting for me, far beyond gassed up subway stations and busy hospitals. The fact that society, in this case represented by the victims in part I, is painted as rather unwelcoming and insensitive made the questions spark more brightly in my mind.

I've almost been member of a cult myself. I went to a "cult session" with a friend, thinking we'd just take philosophy lessons in French. We had no idea it was a cult at the time. Classmates were all very vulnerable and isolated people, looking for more philosophy in their lives, guidance, companionship. I got all that from books and was just there to improve my French so when things started getting weird, with common meals and nocturnal walks in the woods that don't seem to be part and parcel of philosophy classes, I got out of there. The philosophy lessons were getting a bit too one-sided for my taste. But it did give me a first-hand experience of how organisations like these operate. They fill a void. A void that society doesn't want to acknowledge? A void that it can't acknowledge? Society, for some people, doesn't hold all the solutions because it doesn't even get to asking all the questions. Where do these people go? Are cults always bad? In Aum Shinrikyo a lot of things seemed to work well, and it exists now under another name, minus the violent intentions. But how can a group of people, declaring themselves outside of society, function within that inescapable framework? How to avoid anger and resentment between belongers and non-belongers? Are non-belongers childish and selfish? Does society only consist of automatons who don't question anything and keep going with the flow? They remain open questions, but questions that merit being asked once in a while.

___

I tried to repress the Urge. That specific, overpowering longing that all Goodreads-reviewers are familiar with. But the desire to slap stars on stuff has prevailed. The story can't be evaluated given it's an objective narrative of what really happened, told by the people who were in the midst of things. How do you give something as personal and real as that any stars? Also Murakami himself, through his essay, observations and choice of questions, shows a very personal side that I don't really feel like evaluating, however rigorous, refined and variegated the five-star-system may be. But that doesn't mean Underground stands above criticism, and I feel this book would have gained a lot if Murakami employed the same interview style with the victims as he did with the cultists, and if he would have returned to them at a later stage. Sarin has long-lasting effects, and one year after the gas attack isn't really long enough to measure what impact it had on the Japanese psyche. In this way, Underground missed an opportunity, but at the same time it delivered on what it set out to do in this review's opening quote, and even more, because I don't think observations made here are restricted to the Japanese. For me this book was central station, with many tracks of questions on what it means to fit into society and what the options are if you don't.

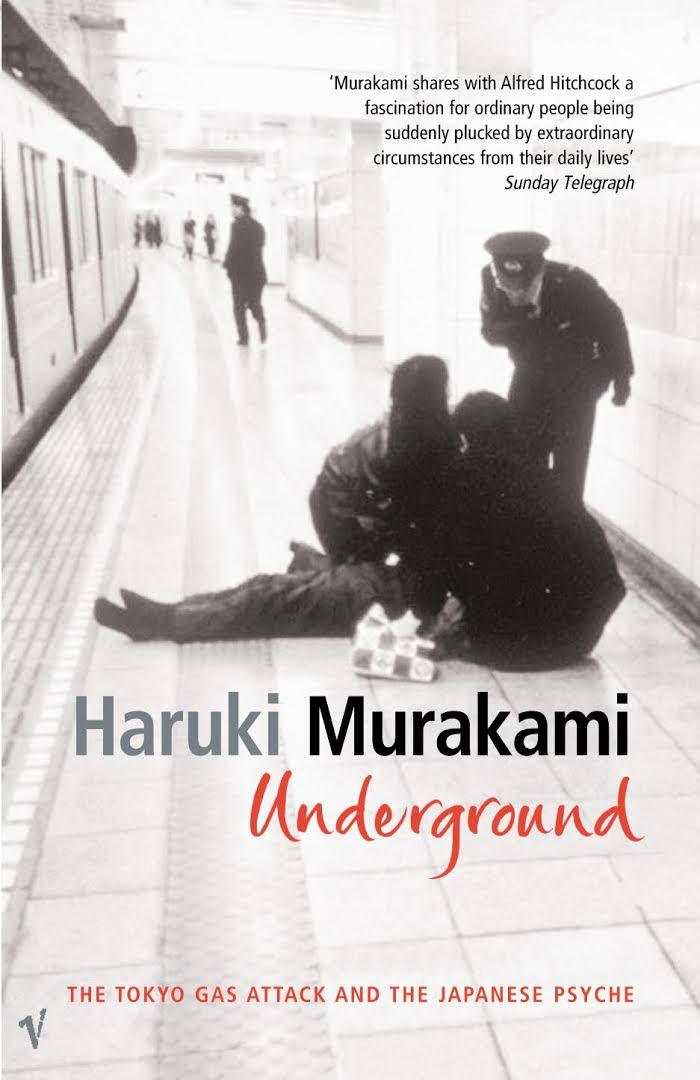

A last word on the cover art for this book in order to drop a name I've been a long time fan of. All Murakamis I have bought are from Vintage, with artwork by Noma Bar (also known for cover art for Don DeLillo's books). Noma Bar always manages to very efficiently show two or three things at once, usually in symmetrical fashion. In this particular case the perspective of a subway station and the sense of danger have been perfectly brought together in a powerful image, that is pleasing to the eye to boot. Check out his other works if you like, they're all over the internet. and all over my bookcase too :-) -

El 20 de marzo de 1995 un atentado terrorista tuvo lugar en diferentes líneas del metro de Tokio, este se cobró la vida 11 personas y dejó secuelas físicas y psicológicas a otras miles. Este atentado fue perpetrado por la secta religiosa Aum. Varios de sus miembros fueron elegidos por su líder para que esparcieran el terriblemente venenoso gas sarín dentro de los vagones del metro en hora punta, tratando de conseguir afectar al mayor número de personas. Ante la falta de información real, sin ser filtrada por los medios y ante la evidente falta de reflexión por parte del gobierno japonés e, incluso, sus ciudadanos, Haruki Murakami siente la necesidad de invesigar sobre el tema, y durante varios años se dedica a entrevistar a las víctimas supervivientes, y también a algunos miembros de la secta, en un intento de comprender como pudo ocurrir semejante situación en el considerado “país más seguro del mundo”.

Realmente me ha parecido super interesante todo lo que esperaba encontrar en “Underground”, pero me ha parecido incluso más atrapante lo que no esperaba descubrir en sus páginas, ya que me pareció incluso más importante. A través de las diferentes entrevistas sobre la experiencia de cada víctima ante el atentado, el lector puede hacerse una idea de como vivió este cada una, en relación a su familia, a su salud y, especialmente, a su trabajo. Y es que lejos de ser lo más interesante el atentado en sí, los antecedentes que lo provocaron o las consecuencias que tuvo, donde “Underground” aloja todo su valor es en la radriografía que hace de la sociedad nipona. Una sociedad de la que llevo toda la vida leyendo y viendo cosas, pero sigue sorprendiéndome a día de hoy.

La primera cosa que destaca y que se repite con cada entrevista, es que todas las víctimas, pese a sentir malestar, en algunos casos de tal gravedad que los lleva casi a la muerte, tenían la obsesión de no llegar tarde al trabajo, aunque tuvieran que llegar arrastrándose. A día de hoy, el competitivo (y explotador) mundo laboral japonés no es algo desconocido, pero no ha sido hasta leer este libro que he sido realmente consciente de lo dura que es la situación. Gente a punto de morir, anteponiendo llegar al trabajo a su propia salud, a su propia vida. Impactante. Pero es que es algo que se nota hasta en lo más básico. Cuando Murakami inicia las entrevistas, cada entrevistado habla brevemente sobre su vida, y mientras que estos libremente deciden no dedicar nada más que una o dos líneas a su familia, amigos o aficiones, sí que dedican varios párrafos o, incluso, varias páginas para hablar de su vida laboral. El trabajo se convierte en la única valía del individuo. Esto pasa en prácticamente todos lados, pero lo que ocurre en Japón llega a asustar. La trampa está tan interiorizada, que es imposible salir de ella.

Murakami comparte reflexiones muy interesantes sobre la especial vulnerabilidad de un país como Japón para caer en las garras de una secta. Ese sentimiento de “solo la sociedad importa y el bien de esta en su conjunto”, arrastra a la gente que no siente que encaje en esta a sentirse apartada y a buscar refugio allá donde pueda sentirse arropada, donde sienta que importa. Creo que es un acierto total que el volumen incluya entrevistas a gente que estuvo, o sigue estando en la secta, porque el contraste entre unos y otros hace una radiografía brutal de la sociedad japonesa.

Otra reflexión constante es la conducta tan natural en los japonesas de evitar hablar o pensar sobre aquello que ocurre y se sale de la norma. A través de las entrevistas descubrimos que todos los implicados en el suceso, de una manera u otra, comparten la misma intención, olvidar el tema, como si nunca hubiera pasado. Creo que los pensamientos de Murakami ante lo peligroso que es esto, pues los problemas no se solucionan metiéndolos en un cajón, ya que pueden volver y repetirse continuamente, es extremadamente acertada. Al final, esta actitud, hace un resumen bastante claro de la sociedad, y de como están enseñados para ser funcionales para esta, sin pensar demasiado sobre ellos mismos o las cosas que les rodea.

Lo único que me ha faltado, pese a que al final el autor explica algunas cosas, es una análisis previo de la secta Aum, de su creación y sus intereses, que ayude al lector a situarse mejor. También es cierto que las entrevistas son tantas, y a veces tan parecidas en cuanto a lo que cuentan las víctimas, que se pueden llegar a hacer algo repetitivas. Por lo demás, he disfrutado muchísimo este libro, y como he dicho, no por el suceso y el análisis de este, si no por la presentación de una sociedad que se me ha hecho más lejana e indescifrable que nunca, y eso que llevo interesándome por la sociedad japonesa más de veinte años. Me ha impactado mucho más de lo que esperaba que fuera a hacerlo antes de leerlo. Ha sido una acierto leerlo en lectura conjunta con @carolrodriguez83 porque ambos amamos a Mura yle hemos sacado muchísimo jugo. -

"The truth of whatever is told will differ, however slightly, from what actually happened. This, however, does not make it a lie; it is unmistakably the truth, albeit in another form."

It's probably unusual to pick a non-fiction as my first read by Mr.

Haruki Murakami, but I believe it's one of my better decisions yet because I was able to get to see exactly how Mr. Haruki's writing process works, his dedication to research and details, wanting to stay true to each interviewee's account; how he devoted a two-hour interview with each interviewee and another three to four hours each interviewee of the former or current members of the Aum cult to get a concrete grasp of each person's character; how even just locating the victims/persons involved in the Tokyo Gas Attack had been almost an impossible task and even after finding them, only a small percent was willing to be interviewed. It's incredible, his passion and dedication to write this book and for this alone, consider me an instant Murakami convert.

The book is a non-fic literary collection of short stories, real life stories of the individuals, (a random train passenger, a train officer, the an Irish Jockey, etc.) affected during the Tokyo Gas Attack. Their experiences of the same event may be different but all are relevant and life changing.

This book is also specifically written to take a deep look into why these things happen and what we, the humanity, can learn from them. Cult members are normal, even beyond average people who have no avenue to express their feelings that they end up joining in something that promises them utopia. This is what we should be watchful of.

Mr. Murakami, himself, learned and saw what it really meant to be Japanese when faced with catastrophe and earnestly agreed that there are existing holes in the Japanese society's system which is true for any society. True, there is no clear cut solution to the many societal problems we deal with but perhaps a basic awareness is the first step toward it and one can easily do it by reading this book. -

The bestselling novelist Haruki Murakami gives a Studs Terkelish treatment to the Tokyo sarin gas attacks of 1995 which killed 12 and injured hundreds. There's a great deal about Terkel's methods to like (when Terkel uses them), but they fall flat here. I don't think the oral history treatment works well in this instance, in which every victim is in the same location (the subway system) and is subjected to the same assault; the approximately 30 victim accounts are extremely repetitive, which becomes numbing, and while horribly tragic, also boring. (On the upside, I am now familiar with all the symptoms of sarin gas and will know what's happening if I come under attack.) The same is largely true of the cult members' accounts. (None of the cult members he interviewed were involved in the attacks, and did not know about them in advance.) Not surprisingly, many people who join cults are having problems living "normal", well-adjusted lives; they tend to be society's misfits; they usually hated school. While they generally acknowledge that the gas attacks were wrong, some of them remained with the Aum Shinrikyo cult (which still exists, but under state surveillance).

Murakami had been living abroad for eight years in Europe and the U.S. when he decided to write Underground. He felt it was time "to probe deep into the heart of my estranged country." The Kobe earthquake and the sarin gas attack, occurring within three months of each other, helped focus his probe. He finds that passivity and unthinking deference to authority are part of the Japanese psyche, as evidenced by the slowness to take affected trains out of service, the inadequate emergency and medical response to the attack, and by the cult joiners. He tries to figure out why the Aum leadership, whose members were well educated professionals, could have participated in terrorism. He concludes that the real world, with its imperfections, contradictions and defects, dissatisfied them. They sought utopias, which gave them a sense of purity of purpose.

I'm a nuts-and-bolts kind of person. I want to know how the sarin was manufactured. How did they get it into plastic bags without poisoning themselves? How were the bags sealed - was it one of those vacuum-pack systems you can buy from an infomercial? Did they do a dry run to see if anyone would be suspicious of bags being dropped? Murakami presumably isn't motivated by these kinds of questions, which is why I'm often more interested in reading terrorist trial transcripts than psychological investigations. -

Được em Vy giới thiệu. Do sở thích cá nhân nên không khoái tiểu thuyết của Murakami, nhưng thấy tác phẩm phi hư cấu nào của ông cũng tuyệt cả. Đọc trong những ngày đi học IATSS ở Nhật. Vừa đọc vừa đi qua những ga tàu điện ngầm trong sách, ga Hibiya, ga Kodemmacho gần ngay khách sạn mình ở. Cảm giác rùng mình.

Mình vẫn cảm giác người Nhật đúng như trong sách, bề ngoài là những người bị đóng vào một khuôn mẫu xã hội quá chật. Bên trong là tầng tầng lớp lớp những xáo trộn nội tâm.

Sách đưa ra cái nhìn sâu sắc vào xã hội Nhật Bản (ít nhất là ngày trước), một xã hội quá an toàn, rập khuôn và máy móc đến nỗi cả hệ thống và con người bị đóng băng và tê liệt khi đối diện với thảm họa. Người dân quá phụ thuộc vào nhà nước. Một xã hội khi con người bị khủng hoảng về niềm tin, khi các giá trị sống bị lung lay và đổ gãy. Một nơi khi những con người không tin tưởng vào tiền bạc, vật chất hay phát triển kinh tế bị đẩy ra khỏi rìa xã hội, khi những tiếng nói trái chiều bị áp đi, khi sự đa dạng không được tôn trọng, và bản sắc cá nhân bị dồn nén để nhường chỗ cho quy chuẩn xã hội khắc nghiệt.

Bây giờ, sau hơn 20 năm, người Nhật đã có hệ thống xử lý khủng hoảng hiệu quả hơn, biết cách xây dựng những cộng đồng lành mạnh và bền vững hơn, (công nhận họ cực giỏi trong việc "Build Back Better"). Những bài học đau đớn mà nước Nhật đã trải qua sẽ là kinh nghiệm đắt giá để xem xét và soi mình cho những nước đang trên đà phát triển như Việt Nam. -

On March 20, 1995, Japan experienced its

deadliest act of terrorism (and most serious attack since the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings of 1945) when members of the 'Doomsday cult', Aum Shinrikyo, released the lethal nerve agent, sarin, on multiple Tokyo subway lines at rush hour. 13 people died, 50 were severely injured, and thousands of commuters had to be taken to hospital.

The coordinated attacks shook the nation, known for its social cohesion and low crime rate, to the core, and there was no talk of anything else for a long time afterwards. Some of the main perpetrators were

executed only in July this year; 23 years after the attacks. The attacks had occurred just two months after the

Great Hanshin earthquake, one of the worst earthquakes in the history of Japan, which took the lives of nearly 6,500 people.

Murakami was deeply affected by these two horrific events which occurred in such a short interval, and he published two books in 1997:

After the Quake is a collection of short stories where each one is related to the earthquake. And in Underground, we read the interviews Murakami conducted with some of the victims of the sarin attack: those who witnessed the bags on the train from which the liquid and subsequent gas spread from; those who were working at the station on the day; those who sought to rescue others on the day and also became victims; those who are severely handicapped forever because of the sarin; those who lost a family member from the attacks.

This collection of interviews was a unique reading experience. Murakami interviewed around 60 victims, and we hear detailed accounts of each interviewee introducing themselves, what their lives were like when they got on the train on March 20, 1995, what happened on that day, and how the attacks have affected them afterwards. Several of the interviews are obviously heartbreaking to read (especially the ones with the man whose sister has been hospitalised and is severely handicapped since, and the one with the family members of one of the victims who died that day), while most of them are with those who were affected to a smaller degree; they experienced debilitating symptoms for days or weeks after, but then went back to their normal livelihoods.

Although each account is unique, when you read dozens of them, you notice the similarities in many of them, and how repetitive some parts are. Some may find this boring, but I found it fascinating to read. One of Murakami's goals was to explore 'the Japanese psyche', and I thought you get quite a vivid picture of this through the interviews. An interview with one is an interview with one, but interviewing many brings to the fore how Japanese people think, feel and act in day-to-day life, and in abnormal situations.

When you come face to face with something which sounds as profound or significant as a psyche, a sort of 'modern-day national collective consciousness', you're bound to find yourself automatically reacting to this, this boulder that you find facing you, this hitherto unknown entity which you don't know how you feel about. Is it friendly, or is it repulsive? Can you relate to this new knowledge and understanding, or do you find yourself mocking it, feeling fortunate you are different? We're all going to be on the spectrum somewhere; perhaps, a three-dimensional one that interrelates with the psyche you have, of who you are, and which 'groups' you may belong to.

On the surface, I remember parts like when the interviewee said they get five days' holiday after ten years of working at the company they work for, and he and Murakami talking about this as if it was positive rather than laughable or ridiculous; on the deep end, at the planet's core, I found myself thinking about racial identity, of Japan vs. the West, of growing up in Japan vs. say Australia, and discussing these matters with others. Perhaps one of the reasons I haven't been able to start a new book since closing the last page of this one more than a week ago; I feel there's something bugging me, and I've managed to procrastinate from or put off writing reviews for most of the books in these two years, but this one wasn't letting me. I had to write something about reading this book, and now that I've started, I feel like I could use up the whole 20,000 character limit.

Murakami also had something pulling on him when he read a letter from the wife of a man who'd lost his job after the sarin attacks, in some magazine ; the man wasn't quite the same after that day, and those at his workplace didn't understand him, didn't sympathise with him. "You look normal." They gradually got to criticising him, harassing him, and he couldn't take it any more. Murakami was left with the question, a question towards countless parts of the story: "Why?" And he had to find out what happened on the subway on March 20, 1995, from the people who could tell him.

Would I recommend this book to others? Yes, but not in the same way I'd recommend a novel of his. It doesn't bring enjoyment, hope or excitement; rather their opposites. This book was an important one for me as I'm a Murakami fan, I'm a Japanese person who is often thinking about the Japanese psyche from the inside and outside, and it made me pick up my pen. I'd recommend a novel of his over this non-fiction work any day. But maybe one person who reads this might one day feel that vague need, that tiny urge to read about ordinary people who were going to work, or to a meeting, an appointment, on a subway in the Tokyo underground on the morning of March 20, 1995. And how their lives were forever changed because of a group of murderers. It seemed to be just like any other day; but in reality, some people, and perhaps even a part of Japan, was left forever underground.

September 2, 2018 -

دوشنبه ۲۰ مارس ۱۹۹۵، در صبحی بهاری، زیبا و آفتابی جامعهی ژاپن وارد شوک بزرگی شد.

فرقهی «اوم» توسط اعضای خود در پنج مسیر حرکت مترو، اقدام به انتشار گاز «سارین» نمود و جان دهها هزار نفر را به خطر انداخت و در نتیجه تعدادی از مردم بیگناه جان باختند و تعدادی با صدمات بسیار شدیدی روبرو شدند.

این کتاب نه رمان است و نه داستان، یک ناداستانِ حرفهایست و موراکامی خود میگوید تلاش کردم با نوشتن آن ژاپن را بهتر بشناسم

موراکامی ۹ ماه پس از این حمله، تحقیقات خود را آغاز و حدود یکسال هم برایش تلاش کرد و جنگید.

قالببندی و چینش محتوای کتاب به این شکل است که در ابتدا موراکامی داستان چگونگیِ هر یک از پنج انتشار گاز در خطوط مختلف را بیان میکند، سپس مصاحبههایی که با بازماندگانی که در این حملهی تروریسی جان سالم به در برده بودند، انجام داده بود را قرار داده، پس از اتمام آن با نوشتن یک مقدمه، خود وارد داستان شده و از دید روانشناسی، جامعهشناسی به صورت بیطرفانه به بررسی این رویداد پرداخته است و نهایتا مصاحبهای که با هشت تن از اعضای این فرقهی مذهبی داشته را آورده است.

نقلقول نامه

"اکثر آدمهای دنیا برای رسیدن به رستگاری و سعادت به مذهب پناه میبرند، اما وقتی که مذهب شروع به درب و داغان کردن آدمها میکند، آنوقت باید به کجا پناه ببرند؟"

"وقتی شخصی همه چیزِ یک حادثه یا رویداد را با جزئیات زیادی به یاد دارد، باید شک کرد چون یک جای کار ایراد دارد."

کارنامه

فکر نمیکنم شخصی من را بشناسد و نداند چقدر عاشق موراکامی هستم، اما دلیل نمیشود چشمهایم را ببندم و نمرهی مفت برای کتابش منظور کنم.

برای تلاشها و ممارست موراکامی در راه تحقیقات یک ستاره، برای اینکه به شکلی استادانه حجم و تعداد زیادی مصاحبه را در قالب یک کتاب خواندنی و نه خستهکننده تقدیم خواننده نمود یک ستاره و بابت نتیجهگیری و پندهایی که ارائه داد یک ستارهی دیگر، جمعا سه ستاره برای این کتاب منظور مینمایم.

دانلود نامه

فایل ایپاب کتاب به زبان انگلیسی را دردر کانال تلگرام آپلود نمودهام، در صورت نیاز میتوانید آنرا از لینک زیر دانلود نمایید:

https://t.me/reviewsbysoheil/403

نوزدهم آبانماه یکهزار و چهارصد -

اتمام..

۷ شهریور ۱۴۰۰

ساعت ۱۹:۱۱ -

¿Por dónde empezar?

Este es el primer libro que leo de Haruki Murakami, y como no es una obra de ficción, no me permite juzgar sobre sus dotes literarias. Sí me permite juzgar sobre sus dotes como investigador y entrevistador, y debo decir que es tenaz, detallado y respetuoso.

El 20 de marzo de 1995 miembros de la secta Aum Shinrikyo (se podría traducir como "Verdad Suprema") liberaron gas sarín en el metro de Tokio. Mataron ese día a 12 personas (la cifra subiría a 14 con el paso del tiempo) y miles de personas fueron afectadas.

Murakami se propuso encontrar a los sobrevivientes y entrevistarlos. Tarea nada fácil, por dos motivos: el primero, por la costumbre japonesa de guardar silencio, en especial en cuestiones personales, y la segunda, y más grave, porque la secta seguía activa, varios de los autores del atentado estaban prófugos, y Aum tenía la costumbre de atacar y atentar contra sus críticos. De modo que fue un acto de valentía por parte de muchos prestar su testimonio.

Este es un libro sobre las víctimas. No sobre Aum. Es muy importante que el lector lo sepa desde el principio. Para mí es un gran mérito, porque las víctimas son los grandes olvidados de todos los crímenes. Todos conocemos el nombre de Bin Laden, pero lo más probable es que no podamos citar el nombre de las víctimas del 9/11, solo por citar un ejemplo.

A medida que leemos los testimonios, resulta imposible no identificarse con alguno de ellos. Porque los sobrevivientes eran personas ordinarias que en su mayoría se dirigían al trabajo cuando se vieron enfrentados a una situación de vida o muerte sin aviso previo, y reaccionaron como pudieron. Oficinistas, contadores, estudiantes, personas comunes y corrientes que sufrieron terriblemente. Algunos testimonios son desgarradores, como el de la familia de Eiji Wada, una de las víctimas que falleció y cuya esposa estaba embarazada al momento del atentado. Por otra parte, yo mismo he tomado el metro en Buenos Aires infinidad de veces para ir al trabajo. Me pregunté cómo sería mi reacción en un caso similar: lo más probable es que no me daría cuenta de nada hasta que fuera demasiado tarde. En el metro siempre viajo atestado y pensando en otra cosa para distraerme del bullicio.

También me generó indignación. Todos los atentados terroristas son actos crueles y absurdos, pero en algunos casos, podemos hacer el ejercicio mental de posicionarnos en la mente del terrorista y decir: "Ah, esta es la ventaja política/militar que pensaba obtener". Pero en este caso, Aum no atentó contra un juez o un periodista que los iba a denunciar. Colocaron gas sarín en el transporte público a sabiendas de que matarían a docenas, tal vez centenares de personas, indiscriminadamente. Es imposible no indignarse con semejantes individuos, que pensaron que lo mejor que podían hacer con su tiempo, ingenio, dinero y creatividad era semejante monstruosidad.

Una nota aparte sobre el gas sarín: fue inventado en los años 30 por científicos nazis como pesticida. Al momento del atentado, era conocido principalmente por ser el arma de elección del dictador iraquí Saddam Hussein en su campaña de exterminio contra el pueblo kurdo. En 1988, en Halabja, el sarín fue usado para matar a más de 5.000 personas. Más recientemente, se volvió una vez más tristemente célebre porque el dictador sirio Bashar Al Assad lo usó en 2013 para matar a más de 1.200 personas de su propio pueblo. Es sumamente tóxico, y puede matar tras la exposición a pequeñas dosis. Incluso si no mueres, puedes quedar con secuelas neurológicas permanentes. No por nada es un arma de destrucción masiva, y su uso por parte de Aum dice mucho sobre su falta de respeto por la vida humana.

Después de leer el libro, que tiene algunas entrevistas con doctores y otras personas, pude sacar las siguientes conclusiones: 1) Los medios japoneses trataron el caso de manera muy sensacionalista; 2) Los servicios de emergencia no estaban preparados para el ataque. Claramente no habían previsto la posibilidad de un atentado con gas, lo que es hasta cierto punto lógico porque hasta entonces muy pocos grupos podían sintetizar, trasladar y liberar esa clase de armas y 3) Lo que es menos excusable, la policía mostró una gran negligencia. Subestimaron gravemente el peligro que representaba Aum. La secta no surgió de la nada y luego cometió el atentado: hacía años que estaban involucrados en actividades criminales. Secuestraron y mataron a un abogado y su familia que los denunciaba. Estuvieron involucrados en un incidente previo también con sarín.

El autor buscó con su libro no solamente mostrar la historia de las víctimas e intentar que la sociedad las tratara con más consideración (muchos sufrían discriminación ya que el sarín, si bien les dejó secuelas, no eran visibles); también quiso advertir que si el trato del atentado se limitaba a demonizar a los responsable, y no a investigar las causas que llevaron a que surgiera la secta y ganara tanta fuerza, podía volver a suceder.

La plana mayor de Aum se componía de personas con excelente educación académica: físicos, químicos, etc. Lo que contradice el estereotipo de que las sectas captan a los ignorantes. No es así. Las sectas buscan personas vulnerables, ya que sea porque se sienten alienadas del mundo, porque sienten que fracasaron en la vida, porque vienen de sufrir una gran pérdida... La secta las detecta y llena ese vacío. Así comienza el lavado de cerebro.

No importa la formación académica: cuando te comprometes con una secta, entregas tu capacidad de análisis crítico. Todo lo que dice el líder suena lógico, aunque sea una locura. Si el Líder te dice que el cielo es verde, el cielo es verde. Si te dice que la Tierra es plana, es plana. Si te dice que pongas gas nervioso en el metro, lo haces.

Aum también reclutó mucha gente joven que se sentía desencantada con el mundo moderno, en especial con el Japón de los años 80 y 90: una sociedad donde el crecimiento económico desenfrenado llevó a un materialismo excesivo.

En resumidas cuentas, un libro excelente, que hace una gran contribución a la verdad histórica y trata con gran empatía a las víctimas. -

Šo ir grūti kaut kā vērtēt ar zvaigznēm, jo kā gan vērtēt cilvēku atmiņas. Murakami intervēja zarīna gāzes uzbrukumā cietušos un Aum kulta esošos vai bijušos dalībniekus un šīs intervijas publicēja. Viņš centās iedot šiem cilvēkiem sejas, izprast notikušā cēloņus un sekas. Pirmā daļa (cietušo intervijas) ir vienveidīgas, jo visi steidzās uz darbu, nesaprata, kas notiek un tā tālāk. Otrā daļa (kulta locekļi) ir daudzveidīgāka: no apgarotiem cilvēkiem ar rozā brillēm, līdz vardarbību piedzīvojušiem atkritējiem.

Kulti ir ļaunums, tas ir galvenais, ko par šo visu pateikt. -

This is actually two books. Part I (1-223), titled "Underground" (Andaguraundo) was published in 1997; Part II ("The Place that was Promised") was written and published separately the following year.

Part I consists of interviews with the victims (see updates; this section is too long and is tedious). Part II consists of interviews with members and former members of Aum Shinrikyo.

And this is where things get really weird....

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aum_Shin...

The members of this cult -- who resemble a cross between the Moonies and Lyndon LaRouche -- are uniformly described as ordinary (read: "mediocre") Japanese who were nonetheless interested in the "deeper" problems of life. All of them describe feelings of alienation -- of feeling that there was "a hole in them", something "incomplete". Murakami points out, in one of these interviews, that adolescents who get interested in the question of meaning, usually start reading books -- philosophy, and so forth. But these individuals report that they were not readers. They simply relied on their intuitions....

Aum held to what is known as Vajrayana Buddhism -- which, inter alia, suggested that murder can, in the hands of the enlightened, be a "fast path" to salvation -- (that is, for the salvation of the murderer...)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vajrayana

Murakami's point in all this, is that we should study these individuals not to find out what "they" think -- but to cast a reflected light back upon "us" -- the society (Japan's) that produced them. As he says (229):

"Or rather, 'they' are the mirror of 'us'.... Now of course a mirror image is always darker and distorted. Convex and concave swap places... light and shadow play tricks. But take away these dark flaws and the two images are uncannily similar... Which is why we avoid looking directly at the image, why, consciously or not, we keep eliminating these dark elements from the face we want to see. These subconscious shadows are an 'underground' that we carry around within us, and the bitter aftertaste that continues to plague us long after the Tokyo gas attack comes seeping out from below."

A strange book. -

Jak dla mnie trochę za długa, ale rozumiem decyzję Murakamiego o napisaniu tego reportażu dokładnie w tej formie. Brakowało mi również dokładniejszego opisu struktur sekty i jej wierzeń, ale tu również - rozumiem, czemu Murakami z tego zrezygnował.

-

my first non-fiction by murakami and it was really really good :) the interviews throughout the book were well executed and eye-opening

-

Words can be practically useless at times, but as a writer they're all I have.

A group of people killed another group of people. I could be talking about a number of things. A description of the present. An incident in history. A prediction of the future. The final result of brainwashing. The beginning of a new era. A cause. A conclusion. The means. The end. A resolution. An excuse. The threat executed by an oppressor. The exigency fulfilled by a nation. Culture clash. Revolution. Murder. Self-defense. Genocide. The right to bear arms. The death penalty. Patriotism. Nationalism. Faith. Religion. Heaven. Hell. Pick a cult, pick a cult: any cult'll do.[I]f someone had fallen down right in front of me, I like to think I'd have helped. But what if they fell 50 yards away? Would I go out of my way to help? I wonder. I might have seen it as somebody else's business and walked on by. If I'd got involved I'd have been late for work...

Japan isn't the United States, the country my country where shootings have indoctrinated the public with the regularity of the weather. One of the interviewees who had been gassed by sarin hypothesized that, had the same incident occurred in a public transport on US soil, every passenger would have been gung ho from the get go and reacted to the incident much more effectively. Perhaps, but that would've depended on the relative level of segregation of the public transport, the social net of the state within which the public transport was contained, the standard deviation of care across the board of passengers under the capitalistic gutting that is the US healthcare system. Fire in a crowded theater, more like. And, of course, the one execution of function the United States is an absolute master of that would vent the fallout of an incident like the Tokyo Gas Attack across decades of reaction: the scapegoat.Haven't you offered up some part of your Self to someone (or some thing), and taken on a "narrative" in return? Haven't we entrusted some par of our personality to some greater System or Order?

I recently caught up with a friend who's been stuck at an underpaid occupation for some time. It was manageable when concurrent with high school and somewhat excusable when conducted alongside college, but now that my friend is out and about with a degree and all, lies involving "experience" and "exposure" and less than living wage don't cut it when financial independence is a simultaneous expectation. Trust In This System And The System Will Reward, and you don't have to renounce the secular life entirely or follow the murderous orders of a cult to do it. The desk job and the standard hours and the cold hard cash may distance and disillusion, but see, I've been part of a genocidal military industrial complex since day one of my existence through no execution of will of my own, so forgive me if my priorities are a compromise of my awareness and my livelihood. There's nothing that saps the strength of continued existence more than the pile up of the little hypocrisies on top of the huge and terrifying paradoxes, so something like Aum doesn't baffle while the Navy advertises its global map of bases before Pixar movies.Later, when the police asked me "Didn't people start to panic?" I thought back on it: "Everyone was so silent. No one uttered word."

It's the same old common denominator of death drawing together the dying and the death-dealing once again in a somewhat different environment using somewhat different tools and ideological modus operandi. One thing that's different is I can let myself trust a little more the truth I'm hearing, cause if I have to read another white person talking as if they know anything about non-white people and getting paid for it before I'm dead and gone, it'll be too soon. Another is that I've gotten over my whole anti-religion fad after years of being told on a theological level morality was where it wasn't and wasn't where it was, so I don't stop at Aum as the ultimate mystery and instead continue on to the government, and the corporate work force, and the fact that a nation not giving a fuck about certain groups of its people will always have consequences. Yet another is Murakami not screwing up his intentions too much, cause while it'd be absurd to believe any of these interviews are candid, the sheer number of instances of Japanese people talking to Japanese people from both sides of a common event results in as close to an honest text as can be achieved in this global age of ours. Both the author and those he interviews throw around the words "crazy" and "insane" too much, and there's a moment of disability inspiration porn that's just plain wrong, but if Murakami wasn't disturbed by how much the sarin victims mirrored the former and not so former Aum members in terms of certain thoughts and feelings to the point of questioning it to this day, I'll eat my hat.If there's someone looking ill on the train I always say, "Are you okay? Want to sit down?" But not most people — I really learned that the hard way.

You can't come together and stay together and act all surprised when the actions of the group reflect on the individual in such a way that is completely different from the side of the story you were initially drawn in through. All that matters is the means by which you trade in the blood on your hands for peace of mind. You don't need religious fanaticism for that.I came to them from the "safety zone", someone who could always walk away whenever I wanted. Had they told me "There's no way you can truly know what we feel," I'd have had to agree. End of story.

-

Domanda 1: come si scrive un buon saggio che parli di un attacco terroristico?

Domanda 2: perché leggere oggi un libro che parla di un attacco terroristico avvenuto 25 anni fa in Giappone ad opera di un gruppo (il movimento religioso Aum) che in Italia nemmeno esiste?

Con questa recensione vorrei spiegare perché per me Underground è un buon saggio e soprattutto perché ha ancora senso leggerlo,anche oggi e anche in Italia.

Underground è composto da due diverse parti: la prima raccoglie le interviste delle vittime dell'attacco col sarin alla metropolitana di Tokyo che hanno accettato di parlare con Murakami, la seconda quelle di alcuni seguaci o ex seguaci del culto di Aum.

Credo che Murakami, che già apprezzo come romanziere, sia anche un abile saggista.

Trascrive raramente le sue opinioni, lasciando che il lettore si formi da sé la propria opinione; le poche volte che esprime i suoi giudizi, questi mi sono parsi equilibrati e non superficiali, né arroganti, perché Murakami non crede di avere tutte le verità in tasca e si pone così sullo stesso piano del lettore.

Le interviste alle vittime sono molte, inevitabilmente i racconti di parecchie persone sono simili, ma ho apprezzato molto che Murakami abbia scelto, per rispetto, di pubblicarle tutte: per molte persone raccontare, e quindi rivivere, quegli eventi deve essere stato difficile, non sarebbe stato molto etico non pubblicare le loro interviste perché non erano "abbastanza speciali". Probabilmente il saggio ci avrebbe guadagnato in "leggibilità" ma, ripeto, sono contenta che Murakami abbia scelto di pubblicarle tutte, dimostrando etica ed empatia.

Nella seconda parte, quella dedicata alle interviste a (ex) seguaci di Aum, la voce di Murakami si fa un po' più presente. Sono interviste molto "attuali" e disturbanti: attuali perché ci permettono di vedere più da vicino il funzionamento di una setta (in parte perfino di un gruppo terroristico) e disturbanti per il loro connubio tra normalità e follia Da una parte ci mostrano la relativa normalità di molti dei seguaci (spesso persone istruite ma che faticano ad adattarsi allo stile di vita contemporaneo) e allo stesso tempo il fatto che molti di questi, ancora oggi, nonostante le prove e le confessioni dei colpevoli, fatichino ad accettare pienamente la responsabilità di Aum nell'attacco terroristico. In particolare, l'intervista ad una ragazzina entrata nella setta in giovane età e che crede di possedere poteri soprannaturali è stata davvero disturbante.

Interessante, oltre che attualissima, la riflessione di Murakami sulle sette ed il loro successo nelle società ricche e competitive contemporanee.

Insomma, ho molto apprezzato questo saggio, interessante e talvolta commovente. Non si legge velocemente ma, secondo me, ne vale la pena. -

مترو از هاروكي موراكامي،پيرو پخش كردن گاز سارين در متروي توكيو (٢٠ مارس ١٩٩٥) توسط فرقه ي اوم شينريكيو با رهبري شوكوآساهارا به نگارش درآمده است.

"مترو" مجموعه ي مصاحبه هاي مستندي است كه توسط هاروكي موراكامي انجام شده و شامل سه بخش است:

١-بخش اول،مصاحبه با افرادي كه در حادثه بوده اند و بسياري دچار آسيب شده اند.اين بخش به شرح روايت شخصي هر فرد در روز حادثه ميپردازد و از ديدگاه فرد در مورد فرقه ي اوم و مجازات آن ها صحبت ميكند.

٢-در بخش دوم،موراكامي راجع به علت نگارش كتاب نوشته است و همچنين بصورت (تقريباً)بي طرف، حادثه ي مترو را شرح ميدهد.

٣-موراكامي قسمت سوم كتاب را به مصاحبه با افرادي از فرقه ي اوم اختصاص ميدهد(افرادي كه همچنان به اهداف اوم معتقد هستند و همچنين افرادي كه از فرقه جدا شده و منتقد اقدامات شوكوآساهارا هستند).در اين بخش،هر يك از افراد در مورد اعتقادات،عامل محرك پيوستن به اوم، ساختار فرقه و همچنين ديدگاه شخصي خود نسبت به اقدامات اوم (به ويژه حمله با سارين) صحبت ميكنند.

+موراكامي خيلي زيبا در مورد پيروان فرقه هاي اين چنيني ميگه كه :

"شايد كمي زيادي درمورد مسائل فكر ميكنند. شايد دردي دارند كه در خود نهفته اند.نمي توانند احساسات شان را زياد خوب به ديگران نشان دهند و به شكلي در رنج اند.نميتوانند برا بيان خود وسيله ي مناسبي پيدا كنند و بين احساس غرور و بي كفايتي سرگردان اند.* آن فرد به راحتي ميتواند من باشم.ميتوانيد شما باشيد *

++ترجمه ي كتاب خيلي روان و خوب بود.

+++موراكامي به همون اندازه كه رمان نويس خوبيه، غير رمان نويس خوبي هم هست😅

++++خوندن كتاب رو بهتون پيشنهاد ميكنم، بخصوص از اين لحاظ كه فرقه هاي اين چنيني در سراسر جهان و قطعاً ايران وجود دارن و "مترو" كمك ميكنه ديدگاه روشن تري نسبت به اقدامات اونا و از همه مهم تر پيروان اين گروه ها پيدا كنين. -

3.5⭐

Trochę za długi był ten reportaż. Myślę, że niektóre przeżycia osób można było pominąć, bo nie miały one bezpośredniej styczności z zamachem. Część pokazująca sektę z zaplecza była najlepsza i bardzo ciekawa. -

Andaguraundo – Yakusoku sareta basho de

Spinta, forse, alla lettura dai recenti attentati di Parigi (13 novembre 2015, volevo qualcosa che mi aiutasse a capire perché gli uomini arrivano a fare tali mostruosità), non sapevo cosa aspettarmi da questo libro.

Non poteva essere il “solito” romanzo di Murakami che, per ovvi motivi, ha abbandonato le atmosfere oniriche tipiche dei suoi racconti; quello che posso dire è che è sicuramente un interessante reportage.

L’interesse suscitatomi è a più livelli. Alla fine le risposte che cercavo non le ho trovate (anche perché, secondo me, è impossibile farlo), in compenso, man man che leggevo, mi rendevo conto che stavo vivendo un viaggio nella giapponesità.

Mi hanno lasciato un po’ perplessa alcune reazioni e alcuni sentimenti che ne sono scaturiti. Parzialmente li ho giustificati perché, come dice anche Murakami la memoria modifica i ricordi e, quindi può essere che la mente abbia rimosso o modificato ciò che non si vuole ricordare, e poi perché non ho la prova (e spero di non averla mai) di come mi comporterei io in una situazione del genere.

Rimane il fatto che mi ha spiazzato la quasi freddezza davanti al disastro che avveniva davanti ai lori occhi;

Mi ha fatto piacere leggere nella postfazione della prima parte, che uno dei motivi per cui Murakami ha scritto questo libro è perché voleva capire meglio il suo paese; direi che ha colto perfettamente l’obiettivo.

E, esattamente com’è successo a lui (e credo non sia un caso), le storie di Wada Eiji e Akashi Shizuko sono quelle che mi hanno più toccato e commosso.

In questi due racconti la rabbia per ciò che è successo è più evidente, nelle altre testimonianze, il sentimento più ricorrente sembra essere la rassegnazione e la fatalità, quasi che esternare rabbia e odio sia una cosa da nascondere.

La seconda parte è ancora più interessante, perché si occupa d’interviste fatte a ex adepti e non, del culto di Aum. Qui, la cosa che più mi ha colpito è che, anche quelli che se ne sono andati, magari anche con rabbia, non rinnegano la loro esperienza ma la ritengo un retaggio importante della loro vita.

Inoltre è da evidenziare che qui non siamo in presenza di disadattati, di povera gente, senza istruzione che cerca una rivalsa verso la società; la maggior parte sono persone con elevato livello d’istruzione, ma che probabilmente vivono lo stesso disagio per motivi diversi. Chi non riesce a conformarsi alla società (sia per motivi spirituali, sia per quelli più banali) è visto con diffidenza. Sono degli esclusi per via delle rigide regole sociali e quindi ugualmente incapaci di poter esprimere il proprio valore, con il rischio di diventare una facile preda di chi vuole approfittarsene.

Murakami riporta una citazione di Nakazawa Shinichi “quando un movimento religioso possiede del tutto i suoi seguaci, quel movimento non è più valido” e anch’io penso abbia ragione. -

Un libro salvaje y caotico que nos muestra a una sociedad que nos sorprende cada que conocemos algo nuevo de esta.

Las entrevistas pueden llegar a ser repetitivas ya que todos cuentan lo que sucedió pero Murakami indaga mas en el interior de la personas afectada y en su vida cotidiana, las entrevistas son amenas y esto nos hace ponernos en el lugar del entrevistado.

Murakami adentra al atentado con un epilogo y nos presenta las entrevistas que fueron organizadas conforme las lineas del metro afectadas. Murakami fue severamente criticado ya que el libro solo se centraba en los afectados y solo veíamos una cara de la moneda y para ello, Murakami entrevistó a adeptos de la secta AUM, me fue de buen gusto conocer lo que era AUM y como este caos se fue formando y como sucedía el lavado de cerebro.

Un libro muy importante. -

[library]

This is a book about the sarin attack in the Tokyo subway system on March 20, 1995. As you would expect from Murakami, it is thoughtful and careful. It consists primarily of interviews; the first part, Underground, is interviews with survivors; the second part, The Place that was Promised, is interviews with members and former members of Aum Shinrikyo, the cult responsible for the attacks.

The translation, insofar as I can judge, seems good. I hope it's accurate. The one thing I would have liked was for more Japanese words to be included along with their translations--there are several words that get used frequently by the interview subjects that I would like to have the original word for, simply because they seem so important. That's a quibble, not a real defect in the translation, and is probably highly idiosyncratic.

I have two reactions to this book. One is the writer's reaction to everything, including their own personal disasters of overwhelming magnitudes: how can I use this in a story? It always feels like a callous and insensitive reaction, and I'm generally reluctant to articulate it for that reason, but it's actually the opposite, because it's asking, how can I take this experience into myself and turn it into something I can send out again that other people can read and understand and empathize with? Which insofar as I'm willing to argue for a higher purpose to storytelling (aside from just, people need stories to stay alive and sane), is the higher purpose I would argue for. So, yeah, on that level, this is a great book for worldbuilding writers to read to understand the depth and complexity that our worldbuilding most often lacks. I say this not to equate modern Japan with an imaginary country, but to say that our imaginary countries need to aspire to be as deep as Japan is in Murakami's work here (yes, that's a pun; yes, I meant it). If art is going to imitate life, it needs to do so consciously and carefully and with the best understanding we can bring to the table of what we're trying to imitate. And it works better if we read about a city we don't know so that our own familiarity doesn't blind us to how much information is being presented. I don't know a great deal about Japanese society in general, or the city of Tokyo in particular, so this was a window on an alien world for me (using "alien" in the Ruth-amidst-the-alien-corn sense, not the aliens-from-outer-space sense), and I found it fascinating. As someone who's trying right now to invent a city that has a true, deep, four-dimensional presence in my narrative, this was a kind of textbook of all the things I need to think about and understand to make that kind of verisimilitude possible.

This book was an amazing worldbuilding demonstration, though, precisely because Murakami isn't worldbuilding at all. He's telling us (and here I mean "us" as both Japanese readers and the Anglophone readers of the translation) about a real place and real people and a real tragedy that happened in 1995. He's not trying to present 1995 Tokyo to readers of a novel; he's trying to come to grips with a terrible event in his own life and his country's life.

(This is why you should occasionally branch out into nonfiction, even if you write fantasy, so that you get Tokyo, for example, as it was in 1995, not Tokyo as filtered through a writer's imagination and tailored to the needs of a story.)

And that's where the writer's reaction blends into the reader's reaction, which is that this is a fascinating book about a terrible tragedy. Murakami admits he's an amateur interviewer, which he makes up for by being patient and thorough and manifestly a good listener. The survivors' accounts are vivid and telling: they capture how tragedy enters your life without your suspecting its existence and how it alienates you from your own life. Also how confusing a disaster is as it unfolds. (Which is a pretty good practical takeaway, if you need one.)