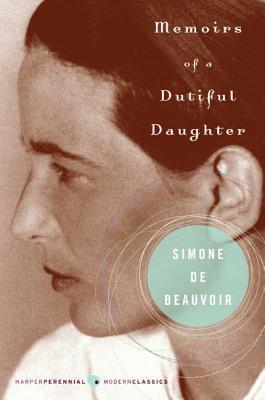

| Title | : | Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0060825197 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780060825195 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 359 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1958 |

She vividly evokes her friendships, love interests, mentors, and the early days of the most important relationship of her life, with fellow student Jean-Paul Sartre, against the backdrop of a turbulent time in France politically.

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter Reviews

-

“…but all day long I would be training myself to think, to understand, to criticize, to know myself; I was seeking for the absolute truth: this preoccupation did not exactly encourage polite conversation.”

Paris, 1908, and Simone de Beauvoir enters the world.

Born into a bourgeois family this beautifully deep and intimate account of one girls journey into early womanhood is both a fascinating and intelligent read. From her young spirited days as a child, to an intricate student life where literature and philosophy would play a pivotal role in shaping the future, to the beginnings of a blossoming friendship with Jean-Paul Sarte, Simone would become a leading figure in the roots of both feminism and existentialism, a true independent voice the the 20th century.

The early years.

Having the same attributes as any girl should have, Simone looked at the world even at a very young age with eyes wide open, she had the characteristics that any parent would wish for in their child, intelligent, pleasant to be around, willing to learn, listen, and play happily with sister Louise.

But she was also an independent thinker, ahead of her years, asking questions that someone of this age shouldn't even be interested in. Her education was a top priority, and Simone was always thinking ahead, deeply passionate for her Mama and Papa, they were her salvation, but the overly protected nature they showed had both good and bad points regarding her development. A family of devout Catholics, the de Beauvoir household was certainly a strict one, I guess it's easy to say that where today's young learn about things they shouldn't from the internet and so forth, back then books made a huge difference in ones self-discovering and learning about life, her mother would reiterate there are books for you and there are books for us, and was constantly keeping an eye on what she was reading. Reading was a big deal for Simone, spending weekends and evening with her head in book. There were two books in particular that had a lasting impression, 'Little Women' and 'The Mill on the Floss', both featuring female characters that Simone felt so strongly about she was driven to tears. It's safe to say that from the age of about twelve Simone's perception of women was changing, her father, a hard working banker believed a women's place in this world was either in the kitchen or the bedroom, and over the early teenage years the relationship with her parents would often bring conflict, but she remained very close to her sister, and had a good friend in Zaza who she spent plenty of time with. Females were definitely her comfort zone.

And there was one question she just couldn't figure out, "how can a women fall in love with a man, whom she may have only known briefly, and replace Papa who had been loved for her whole life"?.

This would constantly be a problem she just couldn't comprehend, Simone had no plans to fall in love, to wed, to have children, to live a wife's life. She just wanted her own, on her own terms.

In the later teen years, when a student, this thought process would change, well only slightly.

The Student.

Having excelled at school but also battling adolescent insecurity, her loss of faith, and the drive for her independence, Simone was very clear she wanted to be a writer, and took to start writing a novel as well as studying deep and philosophical work at the Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève.

She would remain close friends with Zaza, fall in love with a charming young man in Jacques,

and make many new student acquaintances at the Sorbonne. She became fascinated with Robert Garric, a speaker of French Literature trying to bring culture to the lower classes after apparently giving up a promising career at the university, this she felt so strongly about and regularly sat in on some of his talks. Here Simone fell in with Jean Pradelle and Pierre Cairaut, dedicated left-wingers and a small group was set up to discuss various important matters concerning the social classes, possible war looming, as well as Philosophy. This would eventually lead her to cross paths with Jean-Paul Satre, and possibly the biggest moment in her life.

Taking Simone under his wing, Sarte always said he prefered the friendship with that of women more than men, and it's as if the two where just destined to meet. Something great was building, they could both feel it, a new direction was taking shape, which would lead to the birth of existentialism, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Superbly written, and classed as autobiographical, which it is, but the grandest thing of all is it kind of reads like a coming-of-age novel, and it's so personal and heartfelt, you start to think it's an intellectual story rather than an actual real life, but a real life it is, a courageously defiant account of a woman breaking free, and showing a determination to follow her own path, not one already mapped out for her. -

الجزء الأكبر هو في الصراع بين إيمان الطقوس و إيمان الرروح ثم الصراع بين الإيمان و المادية و خلال ذلك استكشافها للعالم و للأشياء و تغير تلك الرؤية كل مرة بتغير نظرتها الفلسفية.

ذلك أن أبي لم يكن يذهب إلى القداس و كان يبتسم حين كانت عمتي مارجريت تعلق على معجزات لورد و هذا يعني أنه لم يكن مؤمنا. غير أن هذا التشكك لم يؤثر علي لشدة إيماني بالله .. و مع ذلك فقد كنت أعرف أن أبي لا يخطئ قط. فكيف أفسر ارتيابه بأوضح الحقائق؟ و لكن بما أن أمي التقية ترى موقفه هذا طبيعيا فلم يكن لي مناص من تقبل موقف أبي. و كان من نتيجة ذلك أني اعتدت اعتبار حياتي الفكرية التي يجسدها أبي و حياتي الروحية التي توجهها أمي ميدانين مختلفين. فإن القداسة لا تمت بصلة إلى العقل. و الأشياء الإنسانية كالثقافة و السياسة و العادات لا تتعلق بالدين. و هكذا دفعت الله خارج العالم.على أن وجه العالم قد تغير تحت ناظري. فقد شعرت في الأيام التي تلت إذ كنت جالسة تحت شجرة الصفصاف الفضي. فراغ السماء. و انتابني من ذلك الضيق. لقد كنت في الماضي أعيش وسط لوحة حية اختار الله نفسه ألوانها و أضواءها. و كان كل شيء يدمدم لمجده و عظمته. و فجأة صمت كل شيء. و أي صمت! لقد كانت الأرض تدور في حيز لا تنفذ منه أي عين. و وسط الأثير الأعمى. كنت وحدي ضائعة على سطحها العظيم. وحيدة. لقد فهمت للمرة الأولى معنى هذه الكلمة الفظيعة. وحيدة. بلا شاهد. و لا محدث. و لا من ألجأ إليه. إن نفسي في صدري. و دمي في عروقي. و هذا الخليط في رأسي. إن ذلك كله غير موجود بالنسبة لأحد. و نهضت و أخذت أعدو نحو الحديقة لأجلس بين أمي و عمتي مارجريت لشدة حاجتي إلى أن أسمع الأصوات.

تقع في الحيرة و الفراغ بعد فقد إيمانها و لا تجد ما تعالج به خواء الروح إلا الفلسفة.كنت أجد عزائي في درس الفلسفة بعد ذلك. و ما كان يجذبني في الفلسفة خصوصا هو ما كنت أفكر به من أنها تمضي مستقيمة إلى الجوهري. و لم أمل يوما إلى التفصيليات. و كنت أدرك المعنى العام للأشياء أكثر مما أدرك تفرّداتها. و كنت أفضل الفهم على النظر. و قد تمنيت أبدا أن أعرف كل شيء. و لسوف تتيح لي الفلسفة أن أروي هذه الرغبة. لأنها تقصد كلية الحقيقة. فتقيم فيها و تكشف لي نظاما و سببا و ضرورة. بدلا من دوامة من الأحداث و القوانين الاعتباطية. و قد بدت لي العلوم و الأدب و جميع الأنظمة الأخرى أقرباء فقراء للفلسفة.

و رغم ذلك يظل شبح الإيمان أو طيفه يطاردها في كل وقت و في كل مكان.و قال لي مرة من غير مرح:

أما الحب فقد أضاعت عمرها في انتظاره هباء و كانت تربيتها الصارمة و متابعة أمها لكل سكناتها و حركاتها من أكبر أسباب الشقاء.

أترين؟ إن ما أحتاج إليه هو أن أؤمن بشيء ما!

فسألته:

ألا يكفي الإنسان أن يعيش.

ذلك أنني أنا كنت أؤمن بالحياة. فهز رأسه و قال:

ليس من السهل أن يعيش الإنسان إذا لم يكن مؤمنا بشيء.لقد انتظرت أسابيع طويلة مثل هذا اللقاء ثم كانت نزوة من نزوات أمي كافيه لتحرمني منه. و هكذا تحققت بذعر من تبعيتي لها. انهم لم يكتفوا بأن يحكموا علي بالنفي و لكنهم لم يكونوا يتركون لي الحرية أن أقاوم قسوة مصيري. لقد كانت أعمالي و حركاتي و كلماتي مراقبة كلها. و كانوا يرصدون أفكاري و كان بوسعهم أن يجهضوا بكلمة واحدة آثر المشاريع إلى قلبي. و هكذا وجدتني جامدة و كان هذا الجمود يدفع في قلبي اليأس.

و عندما يظهر سارتر في النهاية تجد في كنفه الحب و الأمان و العزاء من كل ما في الحياة من تعاسة و شقاء.أما أنا فيخيل إلى أن جميع الأوقات التي لم أقضها معه كانت أوقاتا ضائعة. و في الأيام الخمسة عشر التي استغرقها الاستعداد للامتحان الشفهي لم نفترق إلا للنوم. و كنا نقصد السوربون لنقدم الامتحان و نستمع إلى دروس زملائنا. و كنا غالبا ما نتنزه معا. و كان سارتر يشتري لي عند أرصفة السين الكتب التي كان يفضلها. و يصحبني مساء لمشاهدة الأفلام الكاو بوي التي كنت أحبها. و نجلس على أرصفة المقاهي لنتحدث ساعات طويلة.

النهاية بقصة زازا و براديل مؤلمة و غريبة في الوقت ذاته و كذلك إفراد مساحات كبيرة في المذكرات لقصص الأصدقاء و الخطابات المتبادلة بينهم كانت من السلبيات القليلة لتلك السيرة الذاتية المتميزة ذات الترجمة الممتازة و ان كانت النهاية مبتورة و كأن هناك بقية لم تترجم أو لم تطبع إلا أن بها من الحميمية و الصدق و العذوبة الكثير. -

Be careful of those quiet, nerdy-looking teenage girls, they may grow up to become famous authors. Here's Simone listening to her parents' friends (my translation):

Ils lisaient et ils parlaient de leurs lectures. On disait: "C'est bien écrit mais il y a des longueurs." Ou bien: "Il y a des longueurs, mais c'est bien écrit." Parfois, l'œil rêveur, la voix subtile, on nuançait: "C'est curieux" ou d'un ton plus sévère: "C'est spécial."

Her mother had strict ideas about what Simone was allowed to read herself; many of the books had paperclips inserted to mark the forbidden pages. By the time she was 17, she'd read every single page they had at home. She removed the paperclips, then put them back in the same place when she was done. Apparently her mother never noticed.

They read, and they talked about what they'd been reading. They said "It's well-written but a bit boring." Or, perhaps, "It's a bit boring, but it's well-written." Sometimes, with a dreamy look and a hushed voice, they provided further details: "It's strange" or, in a more severe tone, "It's different."

Oh, and did you know that Sartre got her on the rebound?

-

My introduction to the writing of Simone de Beauvoir is the first of several memoirs she wrote. Published in 1958, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter takes place during the Great War and the postwar years, with de Beauvoir an intellectually ravenous, morally prudish and eternally questioning teenage daughter of a bourgeois family in Paris. Lit with tremendous desire, but, as a child of privilege, very little drama, I related to her life immediately. My childhood in suburban Houston of the 1980s was filled with great anticipation but very little in the way of anything actually happening. The author relates all of this in writing that is absolutely jeweled.

-- One day in the place Saint-Sulpice, walking along hand-in-hand with my Aunt Marguerite who hadn't the remotest idea how to talk to me, I suddenly wondered: 'How does she see me?' and felt a sharp sense of superiority: for I knew what I was like inside; she didn't. Deceived by outward appearances, she never suspected that inside my immature body nothing was lacking; and I made up my mind that when I was older I would never forget that a five-year-old is a complete individual, a character in his own right. But that was precisely what adults refused to admit, and whenever they treated me with condescension I at once took offence.

-- One evening, however, I was chilled to the marrow by the idea of personal extinction. I was reading about a mermaid who was dying by the sad sea waves; for the love of a handsome prince, she had renounced her immortal soul, and was being changed into sea-foam. That inner voice which had always told her 'Here I am' had been silenced for ever, and it seemed to me that the entire universe had foundered in the ensuing stillness. But--no it couldn't be. God had given me the promise of eternity; I could not ever cease to see, to hear, to talk to myself. Always I should be able to say: 'Here I am.' There could be no end.

-- In the afternoons I would sit out on the balcony outside the dining-room; there, level with the tops of the trees that shaded the boulevard Raspail, I would watch the passers-by. I knew too little of the habits of adults to be able to guess where they were going in such a hurry, or what the hopes and fears were that drove them along. But their faces, their appearance, and the sound of their voices captivated me; I find it hard now to explain what the particular pleasure was that they gave me; but when my parents decided to move to the fifth-floor flat in the rue de Rennes, I remember the despairing cry I gave: 'But I won't be able to see the people in the street any more!'

-- Papa used to say with pride: 'Simone has a man's brain; she thinks like a man; she is a man.' And yet everyone treated me like a girl. Jacques and his friends read real books and were abreast of all current problems; they lived out in the open; I was confined to the nursery. But I did not give up all hope. I had confidence in my future. Women, by the exercise of talent or knowledge, had carved out a place for themselves in the universe of men. But I felt impatient of the delays I had to endure. Whenever I happened to pass by the Collège Stanislas my heart would sink; I tried to imagine the mystery that was being celebrated behind those walls, in a classroom full of boys, and I would feel like an outcast.

-- My father, the majority of writers, and the universal consensus of opinion encouraged young men to sow their wild oats. When the time came, they would marry a young woman of their own social class; but in the meanwhile it was quite in order for them to amuse themselves with girls from the lowest ranks of society--women of easy virtue, young milliners' assistants, work-girls, sewing-maids, shopgirls. This custom made me feel sick. It had been driven into me that the lower classes have no morals: the misconduct of a laundry-woman or a flower-girl therefore seemed to me to be so natural that it didn't even shock me; I felt a certain sympathy for those poor young women whom novelists endowed with such touching virtues. Yet their love was always doomed from the state; one day or other, their lover would throw them over for a well-bred young lady. I was a democrat and a romantic; I found it revolting that, just because he was a man and had money, he should be authorized to play around with a girl's heart.

Much of Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter is devoted to Simone de Beauvoir's best friend Elizabeth "Zaza" Mabille, a bookworm whose mother grows to fear that Simone's preference for a ideals will corrupt daughter. The girls grow closer, pull apart and come together again as they move through college. The same goes for Simone's cousin Jacques, who she alternatively detests, loves and decides she'd be grossly incompatible with as a wife. The book is absent of drama and those hoping for a pageant of sex, drugs and rock 'n roll are encouraged to look elsewhere, but de Beauvoir's prism of introspection, intellectual curiosity, virtue, integrity and honesty are an intoxicating read.

Translation by James Kirkup. -

Mémoires d'une Jeune Fille Rangée = Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1958), Simone de Beauvoir

A superb autobiography by one of the great literary figures of the twentieth century, Simone de Beauvoir's Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter offers an intimate picture of growing up in a bourgeois French family, rebelling as an adolescent against the conventional expectations of her class, and striking out on her own with an intellectual and existential ambition exceedingly rare in a young woman in the 1920's.

تاریخ نخستین خوانش سال 1994میلادی

عنوان: خاطرات (چهار جلدی) جلد اول خاطرات دختری آراسته؛ نویسنده سیمون دوبوار؛ مترجم قاسم صنعوی؛ تهران، توس، 1361؛ چاپ دوم 1380؛ شابک جلد یک 9643155285؛ چاپ سوم 1395؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان فرانسوی - سده 20م

جلد دوم: سن کمال؛ جلد سوم اجبار؛ جلد چهار حسابرسی، 1363؛

جلد یکم: در این جلد «سیمون دوبوار» ماجراهای دوران کودکی، و نوجوانی خود را، تا زمانی که دانشجوی درخشانی در رشته فلسفه در «سوربن» شده نقل میکنند: سالهای نخستین در آپارتمان راحتی در بولوار «راسپای» میگذرد، ولی ادباری که در سالهای جنگ جهانی اول به خانواده روی میآورد، پدر و مادر او را ناگزیر میگرداند، که اقامتگاههای کوچکتر و ارزانتری بجویند؛ «سیمون» و خواهرش «پوپت» که بیجهیزیه هستند ناگزیر خواهند بود برای تامین معاش کار کنند؛ پدر بورژوا از بابت این امر که برایش در حکم انحطاطی است به خشم درمیآید؛ او بدون رضایت قلبی شاهد نخستین موفقیتهای دختر در راهی که خود برایش برگزیده میماند؛ تضاد بیرحمانه ای که مایه ی اندوه و سپس سبب طغیان «سیمون» شاگرد سربراه مدرسه «دزیر» و دانشجوی درخشان «سوربن» میشود، او را از محیط بورژوایی خود جدا میکند؛ آشنایی با یک دانشجوی جوان فلسفه که بعدها باید یکی از بزرگترین فلاسفه و نویسندگان سده ی بیستم میلادی شود پایانبخش این جلد است

جلد دوم: در دومین جلد خاطرات، ماجراهایی که در حد فاصل سالهای 1929میلادی تا سال 1944میلادی بر او و «سارتر» گذشته را، بیان میکنند؛ «سارتر» در «لوهاور» و «بوار» در «مارسی»، به کار میپردازند؛ به رغم جداییها و دوریها، دو زندگی برای همیشه به هم پیوند میخورند؛ ده سال صرف نوآموزی زندگی میشود؛ کشفها، دوستیها و سفرها، نخستین کوششهایی است، که در راه نویسنده شدن صورت میگیرد؛ تهدید جنگ، اسارت «سارتر» و فرار او؛ ایجاد جنبش مخفی مقاومت، به ابتکار «سارتر»؛ چاپ نخستین اثر نویسنده و در پایان این جلد: تجلیل از آزادی «پاریس»؛

جلد سوم: در این کتاب، خاطرات سالهای 1944میلادی تا سال 1962میلادی (آزادی پاریس تا استقلال الجزایر) جای گرفته است؛ خوانشگر علاقمند به گشت و گذار و سفرنامه، در این جلد خاطرات، شرح سفرهای نویسنده به «ایالات متحده امریکا»، «چین» و «شوروی» را مییابد، و گذشته از این در خلال سفر «برزیل»، که خود در حقیقت کتابی مستقل است خواهد توانست با این خطه آشنایی یابد

جلد چهارم: در این جلد نویسنده نظم زمانی را که در سه جلد پیشین رعایت کرده، در هم میریزند تا با توجه به کلیه جهات و طبقه بندی مسائلی که برایشان مهم بوده، به یک جمعبندی دست بزنند؛ مترجم برای آنکه نکته ای از خاطرات نویسنده چاپ نشده باقی نماند «کتاب مراسم وداع» چاپ سال 1982میلادی را که شرح زندگی نویسنده در ده سال آخر حیات «سارتر» است در پایان این جلد آورده اند؛ و بدینگونه این اثر بزرگوار تقریبا سه هزار صفحه ای پایان میگیرد

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 10/02/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

Una ribelle compostezza.

La scrittura di questa donna magnifica è qualcosa di straordinario. Mi ci perdo. Mi lascio trasportare, me ne innamoro e poi mi accorgo di avrer letto pagine su pagine in un soffio.

"Durante gli esercizi spirituali che precedettero la mia prima comunione, il predicatore, per metterci in guardia contro le tentazioni della curiosità, ci raccontò una storia che esasperò la mia.

Una bambina eccezionalmente intelligente e precoce, ma allevata da genitori poco vigili, un giorno era andata a confidarsi con lui: aveva fatto così cattive letture che aveva perduto la fede e perso la vita in orrore; egli aveva cercato di riaccenderle la speranza, ma la bambina era contaminata in modo troppo grave: poco tempo dopo egli apprese che si era suicidata.

Il mio primo moto fu uno slancio d'invidiosa ammirazione per quella bambina, più grande di me solo di un anno, e che la sapeva tanto più lunga di me. Poi caddi nella perplessità. La mia fede era la mia assicurazione contro l'inferno; lo tomevo troppo per poter mai commettere un peccato mortale; ma se uno cessava di credere, tutti gli abissi si spalancavano; era possibile che potesse accadere una sciagura così spaventosa senza che uno se la fosse meritata?

La piccola suicida non aveva nemmeno peccato per disobbedienza; s'era soltanto esposta senza precauzione a forze oscure che avevano devastata la sua anima; perché Dio non l'aveva soccorsa? E come potevano, delle parole accozzate insieme dagli uomini, distruggere le prove soprannaturali?

La cosa che meno riuscivo a capire era che la conoscenza potesse condurre alla disperazione."

"Il carnefice non era che un insignificante mediatore tra il martire e le sue palme."

"Una notte intimai a Dio, se esisteva, di dichiararsi. Restò muto, e mai più gli rivolsi la parola. In fondo, ero molto contenta che non esistesse. Avrei trovato odioso che la partita che stava svolgendosi quaggiù avesse già la sua conclusione nell'eternità." -

اكتشفت من خلال هذه المذكرات أهمية الوعي ليكون الإنسان مفكرًا، فيلسوفًا أو حتى كاتبًا مرهف الحس، يفهم التكوين البشري الفردي أو العام، بشفافية وبصدق.

"مذكرات فتاة رصينة أوملتزمة" كتاب تطرقت من خلاله سيمون دوبوفوار لمرحلة أسست لحياتها المستقبلية. إنها الطفولة المتبوعة بمراهقة مليئة بالتساؤلات وصولاً لمرحلة التحصيل العلمي التي انتهت بنضج واعي وخاص للحياة.

أثناء قراءتي لهذه المذكرات ، شعرت كانني أمام شريط سينمائي قديم يمر على أسطوانة حديدية أسمع طقطقاتها ووشوشة الصورة من وقت لآخر. وانتابني شعور أنّ سيمون هكذا كانت تشاهد حياتها حين كانت تسردها. بدايةً توقعت أنّ الأحداث ستأخذني نحو علاقتها بسارتر، لأكتشف أنّ جاك، ابن عمها، هو من أسر قلبها ولسنوات طويلة ورغم كل ما حدث بينهما إلاّ أنه مازال يأخذ حيّزًا من مشاعرها.

سيمون اعترفت وبشكل واضح وصريح أنّها فقدت إيمانها، أو حسّها الإيماني بمرحلة مبكرة من حياتها، واللافت أنّها لم تتعامل مع معتقدها اللاإيماني بأسلوب مستفز، كما يفعل معظم المثقفون الملحدون. فهؤلاء يرجمون كل من يتعارض مع فكرهم ويضعونه بقالب من الجهل والتخلف. بينما ردّ فعل سيمون تجاه من حولها من المؤمنين كان احترام اختيارهم وحيادها تجاه الموضوع على اعتبار أنّ كل إنسان حرّ في اعتقاده سواء آمن أو لم يؤمن. لم يكن إلحادها غاضبا أو مستفزًا أو حتى أسلوبًا لتبدي من خلاله اختلافها عن الآخرين. كان مجرد قناعة وصلت إليها أو مازالت في إطار السعي للوصول إليها. إنها مرحلة الشك.

كانت ترى الأمور بوضوح وتتحدث عنها بصراحة شفافة نضرة لاتدع لنا أيّ مجال لتكذيبها أو النفور منها.

لقد توقعت لما أعرفه من سيرتها الذاتية أن أراها معترضة بشكل قاطع وحاد لفكرة الزواج، لأجدها في نواح معينة مستعدة للتنازل عن جزء من قناعاتها وطموحاتها في سبيل البقاء مع جاك. كانت تبحث عن هويتها الأنثوية من خلال الحب، ومن خلال الشعور بأنها جميلة ومرغوبة. حاولت جاهدة أن تنسق بين عمقها الفكري وشكلها الخارجي. فرأينا الكثير من الوصف للألبسة والأقمشة والمظاهر الخارجية لاسيما فيما يتعلق بصديقاتها أوزميلاتها.

وعلى الرغم من أفكارها التي يعتبرها البعض جامحة وحادة إلاّ أنني اكتشفت إنسانة حساسة تولي أهمية كبيرة لمن ابتسم لها واهتم بوجودها، ربما لتثبت أنها مقبولة اجتماعيًا، الأمر الذي كان يبعث راحة نفسية كبيرة في داخلها.

لم تكن إنسانة مضطربة ، حاقدة أو حاسدة، رغم نفور والديها منها لفترة من الزمن وكذلك والدة أعز صديقاتها "زازا" الشهيرة ماريبل. كانت متصالحة مع نفسها ومع الآخرين، والأمر يعود لنضجها الفكري والعقلي الذي لا يتأثر بالمظاهر وإنما يراقب العمق، عمق الأشياء والأشخاص.

سيمون دو بوفوار كتبت في هذه المذكرات حقبة تأسيسية من حياتها، صداقاتها الأولى، مشاعرها الأولى ونضارتها الأولى. هذه الفترة التي ربطتها بوجود زازا وأنهتها برحيلها حتى كانت جملتها الأخيرة ملفتة في هذا الخصوص حيث قالت:"ولقد فكرت طويلاً بأني اشتريت بموتها حريتي".

وكأنّ زازا هي الشخصية الرديفة لوجودها. الشخصية الإيمانية الراضخة المتقبلة للقواعد والقوانين دون الرغبة بالانقضاض عليها ومخالفتها. وكأنها بداخلها كانت تتخبط بين الإيمان واللاإيمان(لا أريد أن أقول عنه إلحاد لأنني لم أجد أي دليل على إلحادها في كل ماقرأته في هذه المذكرات) كل ما بدا هو رفض، رفض لقوانين صارمة تمنع الانسان من الحب ومن حرية الاختيار.

حتى أنها حين روت حيثيات وفاة زازا أوحت للقارىء وكأنها ماتت بسبب الحب، لتخبرنالاحقًا بصدقها العفوي أنّ سبب وفاة زازا كان داء السحايا.

خرجت بالكثير من الانطباعات لدى قراءتي لتلك المذكرات، اكتشفت خﻻلها أن الوعي يتحكم بالسرد اﻷدبي ولو أننا ندرك خلفه الكثير من المشاعر المكبوتة التي تتيح للقارئ التطلع إليها بوضوح. وصلت بالنهاية لخلاصة مفادها أن الكاتب الحقيقي والفيلسوف الحقيقي والمفكر الحقيقي هو الذي يحترم فكر وفلسفة ومعتقد اﻵخر دون اﻹساءة والتبخيس به ودون محاولة فرض آراءه على اﻵخرين. سيمون دوبوفوار لم تكن مقتنعة بأنها وصلت للمطلق فهي مازالت في بحث دائب عن الحقيقة. "مذكرات فتاة ملتزمة " ليست سوى البداية لرحلة ذكريات ستمتد على خمس مجلدات، منها "قوة العمر" وقوة الأشياء". تمكنت سيمون من إثبات جدارتها الكتابية من خلال تلك المذكرات، واستطاعت أن تحقق بكتابتها ما لم تستطع تحقيقه في الروايات.

حول هذا العمل الفكري والأدبي، لايسعني القول إلاّ أنني استمتعت بقراءتي وتمنيت أن لا تنتهي الصفحات ﻷكتشف المزيد من اﻹدراك الواعي لدى الكاتبة والمزيد من الرقي البوحي.

منحتها خمس نجمات بقناعة كاملة لاتشوبها شائبة. -

I was reading Simon Schama's

Citizens about the French revolution, I had got up to the storming of the Bastille, and I thought I'd step back and take a break by reading de Beauvoir's memoirs of her childhood. Goodness what a shock, Schama paints a picture of France on the eve of revolution in which you might struggle to find a priest who believes in God, where disrespect for the royal family is near universal, the ideas of Rousseau and the classical world as an ideal were on all minds, here de Beauvoir pere, while an atheist, is a royalist , the parents censor de Beauvoir's correspondence until she was almost twenty, her loss of faith is a profound blow to de Beauvoir mere. While one of de Beauvoir's friends comes of a family were all the daughters either marry men or Christ. Naturally in such constricted circumstances cousin marriage is frequent and Simone herself spends a fair chunk of the book fixated upon cousin Jacques who in time becomes fixated upon the bottle (not due to her, his trajectory seems powered by a different dynamic). The dowry is an important instrument for transferring capital between generations and maintaining a bourgeois status.

We are introduced to a society which is engaged in fighting a rear guard action against the French Revolution, this you might find reasonable for a memoir from the early days of the nineteenth century, the twist is that de Beauvoir was born at the beginning of the twentieth. The Rights of Man are along with pesky Bolshevik revolutions (destroying the value of de Beauvoir pere's investment in Russian debt) the threats to a careful, cloying, controlled, catholic culture. Simone herself the lucky beneficiary of the world changing about her.

Memoirs and autobiographies are interesting things - they give the author to shape and transform the raw stuff of their life into a narrative, not that will say anything untrue (hopefully) but there is always selection and emphasis going on, perhaps subconsciously - what we chose to remember and prefer to forget - as much as consciously.

I can't say that I am quite certain what de Beauvoir's narrative is, towards the middle of her book I felt it was the loss of Eden. The family unit of her self, her younger sister, and their parents is for her stable and complete, at the same time we read that she is growing out of that life. Since she is loosing her faith at the same time one feels that Eden is a kind of prison state and for the remainder of the book we see her rattling and fluttering against the cage of values and expectations that she was brought up within. She notices her learnt prudishness when she feels shock when people are pointed out to her who are only romantically interested in the same sex.

I felt also that she was engaging with Freud, perhaps not surprising given his intellectual influence during the period of her adult life. She is careful to point out that she was happy being a girl and saw nothing superior about boys (although physically her upbringing was constrained, no swimming, no gymnastics, to the point that when she begins dancing lessons she feels clumsy and awkward, as she is also flushed with certain physical reactions to dancing in couples she gives up dancing lessons ) and that she wasn't envious of them and indeed as a student rather liked male company in different ways. At the same time there was a psychological awareness, particularly here in her discussion of her father, of how his self regard meant he cold never fully share in de Beauvoir's academic success and likely career as a Lycée teacher, as the necessity of her having to earn a living and get a job with a secured pension was due to his failure to be a real man and provide a fat dowry for his daughter so she could be married off. A certain tension in their relationship developed as she passes exams and collects diplomas.

Although she writes Literature took the place in my life that had once been occupied by religion: it absorbed me entirely, and transfigured my life (p.187) and while books play a certain part in her narrative she points out that it is far more the record of moods and prolonged feelings, partly perhaps because from about half way through she mentions that she started to keep a diary and no doubt her emotional state was something she wrote about, this stands in ironic counterpoint to her engagement in studying philosophy which does move her at so profound a level.

Philosophy had neither opened up the heavens to me nor anchored me to earth...I had no fixed ideas of my own, but least I knew that I rejected Aristotle, St Thomas Aquinas, Maritain, and also all empirical and materialist doctrines (p.234).

She seeks for meaning at one stage falling under the influence of a young man who from his experience of comradeship in the first world war was forming a catholic youth movement, this was quite paternalistic in style, for instance de Beauvoir is enrolled to lecture working class men and women on literature. There's an air of searching for a kind of secularised Catholicism at this stage in her life, she likes the ideals of self denial, mortification of the flesh, structure and purpose, so as not to waste her time for a while she gives up on brushing her teeth. One might see in this too the kinds of inter-war cultural developments for a national culture which unified social classes as a precursor to fascism or communism, indeed de Beauvoir pere approves of Mussolini . However young Simone is also moved by the experiences of her friend abroad and of foreigners that she meets, despite her learnt reticence she has a desire for openness both to new experiences (including Gin Fizzes) and new thinking.

In this regard this is a story of self liberation, a fond farewell, or rediscovery from an adult perspective of her childhood self. There is great feeling for nature, what it was to be like on the small estate her grandfather owned in the spring, the flowers, the colours, the cool of the morning as sh sets out to find a cosy place to read. It is a bizarre thing a book largely about an urban childhood in Paris, in which that city barely features, the Luxembourg Gardens get more mentions than the Louvre, it is a very constrained childhood, one senses the chick pecking at the shell. It is the kind of childhood which I guess would be very rare in France today. Of course had life panned out as her parents wished it she would have emerged from the shell of childhood in the parental house to the shell of marriage in the husbands, as it was history intervened, slowly, but with decisive effect and we see her building a different kind of life for herself even if she is still at that point in her life herself looking for some grand unifying structure. -

عذراً سيمون دي بوفوار أنت لم تكوني رصينة علي الإطلاق

فحياتك بين الكتب واستغراقك التام في القراءة والفهم والإطلاع لا يشفع لك هذه الحياة

فحياتك - علي الرغم من أنك في مجتمع فرنسي - حتي بالنسبة لأسرتك لم تكن رصينة

هذا من وجهة نظري .. ومن وجهة نظر مجتمعك آنذاك أيضاً

كانت مشكلتي معك منذ بداية المذكرات أنني انتظر وأنتظر أن تقابلي سارتر

وأن أقرأ مناقشاتكما معا حول الوجودية

ولكني فؤجئت بأنني لا اقرأ مذكراتك انت فقط .. بل مذكرات أصدقاءك

لقد عشت في حياتهم أكثر مما عشت معك

وعرفت عنهم أكثر مما عرفته عنك

وفي النهاية وجدت أحداثاً هامشية للغاية مع سارتر وقد كان أولي بالحديث منهم بكثير

فما وجدته عنه التنزه مع الرفاق والذهاب إلي السينما وتناول الشراب وأنه إنسان مثقف للغاية

وأنك تعترفين انك بجانبه لا وزن لك

حسناً .. ولكني توقعت مذكرات مهمة أكثر

لا يمكنني أن ألومك فأنت حرة في مذكراتك

وأدري بالأحداث المهمة التي تحبين أن تكتبيها

منحتك 3 نجمات لقدرتك علي تصوير الحياة الفرنسية آنذاك

وحديثك عن مجتمعك ونساء أسرتك

والحياة في جامعة السوربون

والحديث عن الفلاسفة في كل مكان وزمان

وفكرة عدم الخوف من الثقافة

ولكني أعتب عليك في شئ عزيزتي .. ليست الوحدة دائماً رفيقة للكتب

وليست الحيرة والتشتت هي النتيجة الناتجة دائماً عن كثرة الفكر

وليست التعاسة في الثقافة

فمن حولك كانوا في حيرة وتعب وإرهاق وعدمية ليس بسبب الثقافة

بل لأنهم لم يرسوا علي ( بر ) أو لم يريدوا هذا البر الآمن

فحتي البر الآمن كان قيداً لهم علي حريتهم

وأنت أيضاً كنت مثلهم ..

فلا تلومي الكتب والثقافة علي ما كنت فيه

! -

I loved this book so much any review will be wholly inadequate. I loved is how she captures the innocence of childhood and the pains her parent took to maintain that innocence far beyond what seems right. I loved the confusion, despair and vanity of adolescences and how she could feel so strongly about ideals that themselves constantly changed. I loved how her idea of self was in constant flux and the richness of her inner life. I love how books meant just so much to her, and all those descriptions of her spending day after day of her youth reading outdoors in some lovely garden just demands the reader should enjoy this book in the same way. Even the smell of this book was intoxicating.

"I loved those evenings when, after dinner, I would set out alone on the Metro and travel right to the other side of Paris, near Les Buttes Chaumont, which smelled of damp and greenery. Often I would walk back home. In the Boulevard de la Chapelle, under the steel girders of the elevated railway, women would be waiting for customers; men would come staggering out of brightly lit bistros; the fronts of cinemas would be ablaze with posters. I could feel life all around me, an enormous, ever-present confusion. I would stride along, feeling it's thick breath blow in my face. And I would say to myself that, after all, life is worth living."

I place this above 'Speak, Memory' on my list of favorite memoirs, and there isn't any higher praise I offer then that! It's absolutely beautiful. If, just once, while reading a book I become so enamored that I gasp it to my chest uttering uncontrollable signs; then that, for me, is an automatic five stars. I probably did that a dozen times or more throughout this book; just utterly lost in the ethereal dreaminess of her passions or shattered by her despairs; especially the end, I sat at work for nearly a half hour, completely still, completely moved.

"At night I would climb the steps to the Sacre-Coeur, and I would watch Paris, that futile oasis, scintillating in the wilderness of space. I would weep, because it was so beautiful, and because it was so useless."

-

The other day, I was waiting for my husband to meet me for dinner, and I had plenty of time to kill so, I went to read at a nearby coffee shop. I had been sitting there for a few minutes when it hit me that I was drinking espresso whilst reading Simone de Beauvoir (in French!!) and listening to Bob Dylan on my iPod. This moment couldn’t have been any snootier if I had tried… that is, until I started laughing – at myself – out loud, to the other patrons’ confusion. I felt I was only missing a beret and a cigarette, and the picture would have been perfect (note to self: carry emergency beret and cigarette in purse, to maximize future poser moments).

But really, reading Beauvoir shouldn’t be considered a snobby read, especially her memoirs! They are very elegantly written, but show a candor and honesty few people are brave enough to have when looking back at their own lives. They are also a fascinating account of how a relatively ordinary young girl grew up to become one of the 20th century’s luminaries of philosophy and feminism; so you know, it's really interesting!

The title is a bit tongue-in-cheek, as Beauvoir was certainly not always a picture-perfect daughter: she isn’t shy to admit she was a brat who threw public tantrums and who was perfectly happy to make herself throw up rather than eat things she did not like. I admit I was surprised to learn how deeply religious she was throughout her childhood and early adult life: considering her intellectual work and the lifestyle she later cultivated, I had not expected her to have contemplated becoming a nun!

Since this book covers mostly her childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, it focuses a lot on her family, her childhood friend Zaza, her love of books, her studies... and her crushes! The very lucid way she remembers the pangs of puberty, the strange and mysterious agonies of trying to understand oneself and others as you grow up were fascinating and moving.

I felt a certain kinship with Beauvoir as I was reading this: her discovery of the complexity of the adult world and refusal to be treated as a child who did not belong to it, her struggle with the loss of faith and her precocious intellectual interests were things I related to deeply. I loved reading her thoughts about the effect "Little Women" had on her, not only because I also love Jo March, but because she thought Jo's relationship with Professor Bhaer to be more desirable than a more romantic alternative, because they have a greater intellectual connection. I simply couldn't agree more.

In fact, the way she saw her relationships with men was amazing: never could she conceive of being with a man who would not consider her an equal and a partner. When she learns that her cousin Jacques, whom she pinned for when she was a teenager, had a working class mistress he pushed aside when came time for him to make a reasonable marriage, she was most mad at him, not for having had a mistress, but for being a cliché. That lack of originality inspired nothing but disdain in her, she simply could not abide the mediocrity.

Her relationship with Sartre is only just beginning when "Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter" concludes, but she knew he'd always be a part of her life because she felt like she had finally found an intellectual equal, who values her mind and her intelligence. Can I just say: "YAS!!!!".

The amazing story of an absolutely amazing woman. I will be looking for the rest of her autobiography! -

I primi vent'anni della de Beauvoir. Uno splendido romanzo di formazione, ma anche un piccolo, prezioso manifesto d'emancipazione personale (pur sofferta), dai condizionamenti sociali, dal trito bagaglio valoriale borghese-cattolico, dai pregiudizi imperanti. La storia della scoperta di sé che, ognuno a suo modo e seguendo indole e sogni, ognuno di noi dovrebbe almeno provare a compiere.

-

couldn't be me but i'll read about it

-

" I was proud to combine in my person a woman's heart and a man's brain ".

What happens when you learn to see the conflicts between what you are, what you believe, and what is around you, and these become unbearable ?

I think that is the question that is being answered in de Beauvoir book.

For me, beyond the pleasure of reading, ( because SB knows how to describe and make the atmosphere ) - it was an instructional book. Especially because it sets out clearly enough the development of a woman's consciousness in an oppressive bourgeois environment, and the ways in which this woman learns to avoid conflicts and to live under pressures that she did not recognize as such.

One of these ways is " partial blindness " , which I think is a somewhat common phenomenon for women who grow up in close contact with a culture created almost exclusively by men. They learn to identify with the male court, to take its way of thinking, and, if they remember, however, that they are women, to see themselves as " exceptions ". To consider that they have been " blessed " with a " masculine intelligence ".

The impression that you are an " exception " , I think - is due to that " partial blindness ", which you do not realize at all, and to live in peace into a world in which you could not find your place, otherwise. The burgeois society of France at the beginning of the last century, considered sexual relations outside or before marriage - to be perfectly normal, of course, only for men. Simone is not interested in women's right to vote, she reads Plato, Leibniz, Nietzsche, and philosophy makes her believe that she has discovered the truth of the world itself, but her confidence cracks when this claim confronts reality, her so-called " privilege " being based on the most flawed of morals.

The book has many interesting passages to discuss.

It made me smile, for example, a phrase that indicates how the mechanisms of an absurd guilt are constructed, which can make a woman's life an ordeal :

" At the age of 5, it was explained to me that if I was wise and godly, God would save France ".. It also made me laugh the way Simone's mother - a fervent Catholic - caught with a needle the " dangerous " pages of the novels her daughter was allowed to read...And she, even though being alone in her room, did not detached them. Why ?

Even from here, a long discussion could begin.. -

"I was born at four o'clock in the morning on the ninth of January 1908, in a room fitted with white-enameled furniture and overlooking the Boulevard Raspail. In the family photographs taken the following summer there are ladies in long dresses and ostrich feather hats and gentlemen wearing boaters and panamas, all smiling at a baby: they are my parents, my grandfather, uncles, aunts; and the baby is me. My father was thirty, my mother twenty-one, and I was their first child."

And later, there was Sartre...

"From now on, I'm going to take you under my wing," Sartre told me when he had brought me the news that I had passed (Sorbonne). He had a liking for feminine friendships. During the fortnight of the oral examinations we hardly ever left each other except to sleep. I was now beginning to feel that time not spent in his company was time wasted."

But Simone de Beauvoir always knew...

"Whatever happened, I would have to try to preserve what was best in me: my love of personal freedom, my passion for life, my curiosity, my determination to be a writer. Not only did he give me encouragement but he also intended to give me active help in achieving this ambition."

This is an outstanding memoir written by a woman who came to know herself, stepped away from the crowd, and put feelings together in prose meant to enlighten all. -

Riletto tre volte, e rileggendolo ritrovo me stessa. Cioè riconosco l'impronta che ha lasciato nel mio sviluppo intellettuale. A questo libro - letto la prima volta giovanissima - devo molto delle mie attitudini mentali. Mi ha aiutato a leggere in chiave intellettuale quel che mi succedeva, ad accettare l'originalità della mia persona (inserita in un universo di originali, cioè unici). A non avere mai paura dei pensieri, a non sfuggire alle conseguenze del ragionamento, a onorare la priorità dell'intelletto. Insomma, le devo molto. Anche alcune "infelicità".

La sua scrittura è fascinosa, così come la sua intelligenza.

E' una biografia leggera, ricca di aneddoti, ma al tempo stesso pesante di analisi lucidissime e perfette, geometriche (a posteriori di 30 anni, e di tante altre letture, so anche come l'ha ricostruita (con omissioni e abbellimenti, ma non toglie niente al suo fascino).

Nel rileggere, c'è anche il piacere voluttuoso, incomparabile e rassicurante di rileggere un libro amato, che non delude nella rilettura.

E' come ritrovare un vecchio amico*, riannodare i fili e sentirsi a casa.

*con un bel caratterino, Simone! Non le mancava il complesso di superiorità. -

Let's say it right away, every morning every week when I had to put this book in my bag because the train was entering the station. It was painful. So the only thing left for me to do, as I walked, was to go over what I had just read, to relate it to me, to my childhood possibly, and to associate these memories with what I knew about Simone de Beauvoir.

How some autobiographies I have read recently seem bland and empty to me now, in the face of this one! Simone de Beauvoir jumps on each evocation of her childhood to dissect it, explain it, draw from it the substance of what will build her over the years.

As well her enthusiasm as a precocious little girl as her tantrums when she tore off at a captivating moment, her ungrateful adolescence, her questions about faith, yet young emotional in the first years of her life. Then her fierce desire free her from the bourgeoisie in which she entangled up just like many of her friends. These meetings, which will forge her, will direct her unceasingly towards discoveries and reflections always in motion.

We will keep in mind his friendship with his sister Poupette and Zaza, his childhood friend, his love for his cousin Jacques, his admiration for Herbaud and finally, Sartre, who will prove to be the one who will remain in his life forever.

Simone de Beauvoir never judges herself; she analyzes and describes the development of her thoughts as a child and adolescent, sometimes resorting to her newspapers from the time and letters received at the time.

This correspondence, let's talk about it, revolves around an aspect of the upper bourgeoisie forgotten today: marriages arranged around dowries and the respectability of families. Young girls suffering from thwarted and impossible loves, boys encouraged to get their hands on low-income young women before entering into marriage. In the 1920s, however relatively independent, passing aggregation, already a teacher, Simone still asking her parents permission to go to the theatre. Losing her virginity before marriage, of course, is unthinkable, and a girl who is still studying at 20 is wasting her time. Who will want her?

The whole bourgeois context of this time gradually gave birth to De Beauvoir's feminist ideas, whose ambition to be someone was commensurate with his intelligence.

Finally, we discover a young Jean-Paul Sartre philosopher to the end and very endearing.

A key reading. -

من یک سالی پولم به خریدن این مجموعه قد نمیداد. یعنی به خریدنش با دسترنج خودم. یک شب که با رفیقم توی یکی از کتابفروشیها از فروشنده میپرسیدم آیا مجموعه را جداجدا به من میدهد یا نه، و جواب منفی را شنیدم، چند دقیقهی بعد صاحب کتابها شدم. رفیقم آنها را برایم خریده بود. این را تعریف کردم که بگویم چه شد که بعد از مدتها فرار از کتاب قطور و حتی متنهای بلند، مطیع و حرفگوشکن نشستم به خواندن جلد اولش. دوبووار جزئیات جامع و مانعی را از کودکی و نوجوانیاش برایمان به بهترین شکل روایت میکند. ترجمهٔ کتاب، نثری تر و تمیز است که در زندگینامهها کمتر چشمم را گرفته بود. فارغ از ترجمه، سیمون دوبووار گفتگوهای ذهنی، محتویات قلب و نگرشِ انتسابی (از خانواده) و سیر تغییر آن به نگرشی اکتسابی را چنان آرام، باحوصله و خوب توصیف میکند که خواننده حس میکند مثل یک همراه نامرئی همیشه کنار او راه میرود و به علاوه، ذهنش را هم میخواند. مدتها بود خواندن کتاب و تماشای «بزرگ شدن/aging» آنقدر به دلم ننشسته بود.

-

Filosofică, dar mi-a plăcut.

"tatăl meu știa că pentru a scrie o operă literară e nevoie de o muncă obositoare, de strădanii, de răbdare; e o activitate solitară."

"Actorul ocolește chinurile creației; lui i se oferă, gata alcătuit, un univers imaginar în care există un loc rezervat pentru el; se manifestă în rol, în carne și oase, în fața unui public în carne și oase; limitat la funcția de oglindă, publicul îi reflectă, supus, imaginea; pe scenă, actorul este stăpânul și există cu adevărat; se simte realmente stăpân."

"O povestire era un lucru frumos, suficient sieși, ca un spectacol de marionete sau o fotografie; percepeam necesitatea acestor construcții cu început, cuprins și încheiere, în care fiecare cuvânt și fiecare frază se distinge, în individualitatea sa, precum culorile unui tablou."

"Mi se părea îngrozitor să trăiești fără să aștepți nimic de la viață."

"Lumea nu-mi mai părea un loc sigur." -

I have admired Simone de Beauvoir since I became enthralled with existentialism in my late teens. I loved her novel "The Mandarins" and considered her a role model. This memoir of her childhood and early adulthood adds insight into the writer and woman she became. Her prodigious memory calls up detailed memories of her sheltered childhood, ages 3, 4, 5, 6 and so on. Too much! I was more interested in her life as an intellectually adventurous university student, but found the accounts of the inner torment and tumultuous mood swings she and her friends experienced exhausting (and indulgent).

-

The short of it: From the opening pages I fell head over heels for Memoires d'une jeune fille rangée (translated into English as Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter but more literally "Memoirs of a well-behaved girl"), the first of four volumes in de Beauvoir's autobiography. It's been a long time since I connected with a book at such a level of visceral sympathy—since I had the feeling "Yes! That's what it's like for me too!," since I felt such a sense of loss upon turning a final page. So there may be a certain lack of critical distance in this post: I'm declaring myself right up front to be a newly-converted de Beauvoir fangirl, and my only dilemma now is whether to break my book-buying ban and order the second volume (La force de l'age) right this second, or whether to hold out for a gift-giving holiday or upcoming trip to France.

And the long: For me, one of the greatest pleasures of Memoires d'une jeune fille rangée is simply watching de Beauvoir's brain apply its lifelong training in philosophy and semiotics to the examination of her own early life. Beginning with birth and ending with the completion of her secondary schooling, some of the most interesting passages in this book map to what are often the "boring bits" of biography and autobiography: de Beauvoir's early childhood. She is such a keen observer, and obviously so well-accustomed to dissecting the way humans perceive and process the world, that hers becomes an early-childhood story unlike any I've ever read before—and it's especially exciting to read about her development in this regard if the reader has some slight familiarity with her existentialist feminism later in life, since she does a complete about-face on many issues. She writes, for example, about her early assumption (age five or so) that language and other signs sprang organically—necessarily and without human intervention—from the things they signify, so that the word "vache" (cow) was somehow a necessary and organic component of the animal itself. In this mindset she could understand letters as objects (an "a," for example) but not as building blocks representing sounds that make up words. In this passage, she recalls the "click" in her brain when she finally, although in a limited way, grasped the concept of a sign:[J]e contemplais l'image d'une vache, et les deux lettres, c, h, qui se prononçaient ch. J'ai compris soudain qu'elles ne possedaient pas un nom à la manière des objets, mais qu'elles représentaient un son: j'ai compris ce que c'est un signe. J'eus vite fait d'apprendre à lire. Cependant ma pensée s'arrêta en chemin. Je voyais dans l'image graphique l'exacte doublure du son qui lui correspondait: ils émanaient ensemble de la chose qu'ils exprimaient si bien que leur relation ne comportait aucun arbitraire.

[I was looking at a picture of a cow [vache], and the two letters, c and h, that together were pronounced "ch." I understood suddenly that they had no name in the sense that objects do, but that they represented a sound: I understood what a sign is. It then took me very little time to learn to read. However, my ideas stopped there. I saw in the picture the exact double of the sound corresponding to it: they emanated together from the thing they expressed, so well that the relation between them involved nothing arbitrary.

One of the many threads running through the book traces de Beauvoir's evolving understanding of signs: where they come from, how they work, and the inescapable gap (despite her early naïvete) between the thing itself and the sign humans have invented to indicate it. There comes a period in her teenage years when language, the necessity of interpreting language, becomes her enemy for just this reason: when we express our thoughts, feelings, and intentions, there is always a chasm between the thing itself—our interior landscape—and our expression of it; often this chasm is only widened when our words are interpreted by another person.

Despite this semiotic difficulty, however, de Beauvoir herself does an impeccable job of articulating her own interior landscapes at different times in her life, not only as personal experiences, but as ontological states capable of dissection by her as an adult. Another thread that is first woven into the narrative very early is the dread inherent in the realization that we change with time, that our present incarnation is different than the person we will be in the future, and in ways currently dismaying or frightening to us. That these changes may cease to dismay or frighten us in the future, before or after they happen to us, doesn't change the dread our current selves feel at being left behind, replaced:Je regardais le fauteuil de maman et je pensais: "Je ne pourrai plus m'asseoir sur ses genoux." Soudain l'avenir existait: il me changerait en une autre qui dirait moi et ne serait plus moi. J'ai pressenti tous les sevrages, les reniements, les abandons et la succession de mes morts.

[I looked at maman's chair and I thought: "I won't be able to sit on her lap anymore." Suddnely the future existed: it would change me into someone else who would say "me" and would no longer be me. I sensed all the weanings, the renunciations, the abandonments and the whole progression of my deaths.

This was one of those jolts of recognition for me: I have a memory very like this, of being at the zoo with my mother and grandmother when I was three or four years old, and overhearing them talk about how unpleasant "teenagers" were. Mom and Grandma probably didn't actually say this, but I got the impression from their conversation that teenagers hate their parents. And it suddenly dawned on me that one day I would be a teenager: would I hate my parents as well? But I didn't want to hate them; I loved and depended upon my parents. Where would this monstrous teenage-me come from, and how would it eat away at the love I currently felt toward my family? I remember an awful feeling of dread, and of impotence: I didn't want to become this future self I foresaw, but presumably I could do nothing to stop it: "I"—the "me" looking at the polar bears—would be consumed in teenage-ness and no longer care about "my" (toddler-age) preferences. Of course the truth was more complicated—I never stopped loving my parents, needless to say—but in a way, my three-year-old self was right: by the time I was a teenager I DID act snotty and unpleasant to them a lot of the time, and I no longer wished (luckily) to regress into the trusting dependence of toddler-hood. I had become a stranger, and no longer wanted to go back; the only way was forward.

De Beauvoir's delineation of this process is fascinating, and she returns to it several times throughout this volume: the dread that precedes a change, and the ontological break that enables us to be in a completely different emotional space after the change, so that our former dread is no longer relevant. Raised devoutly Catholic, for example, she realizes sometime in her early teens that she no longer believes in God. At some point before this realization, she thinks to herself that to lose one's faith would be the most horrible thing she can imagine happening to a person; yet when she herself realizes that it has happened to her, it makes no immediate change in her life; she feels little distress. She had thought that her morality and assumptions about the universe would immediately and drastically be torn asunder, but in fact she retains the tenants of her bourgeois Christian upbringing long after she has stopped believing in God, and only very gradually (years, decades later) comes to reexamine the aspects of that upbringing that no longer make sense to her. By the time she is questioning these assumptions, other things (literature, philosophy, human relationships) have taken the spiritually fulfilling place that religion once held in her life:

La littérature prit dans mon existence la place qu'y avait occupée la religion: elle l'envahit tout entière, et la transfigura. Les livres que j'aimais devinrent une Bible où je puisais des conseils et des secours; j'en copiai de longs extraits; j'appris par coeur de nouveaux cantiques et de nouvelles litanies, des psaumes, des proverbes, des prophéties et je sanctifiai toutes les cironstances de ma vie en me recitant ces textes sacrés. [...] entre moi et les âmes soeurs qui existaient quelque part, hors d'atteinte, ils créaient une sorte de communion; au lieu de vivre ma petite histoire particulière, je participais à une grande épopée spirituelle.[Literature took, in my life, the place that had formerly been occupied by religion: it overran everything, and transfigured it. The books I loved became a Bible from which I took advice and comfort; I copied long extracts from them; I learned by heart new hymns and new litanies, psalms, proverbs, prophecies, and I sanctified all the circumstances of my life by reciting these sacred texts. [...] Between me and these sister souls there existed something, out of reach; they created a sort of communion; instead of living my trivial individual story, I was participating in a grand spiritual saga.]

Although I want to discuss so much more—young Simone's feeling of tragedy at the unconsciousness of inanimate objects; her attribution of her own negative capability to the difference in her parents' belief systems; her relationships with her sister and her best friend; her first meetings with Sartre—I'm already running long. I can't close this post, however, without mentioning the insight that Memoires d'une jeune fille rangée gives into de Beauvoir's feminism. Her father looms large in this history, as both the object of her childhood and adolescent idolatry, and as a conservative blow-hard who says things like "a wife is what her husband makes her; it's up to him to shape her personality," and bitterly regrets the fact that his loss of money means that his daughters will be earning their own livings, rather than marrying well into good society (never mind that they PREFER to earn their own livings; that's not the point). Her father's betrayal of her—he tells her she will have to educate herself and earn her living, then hates her for being a reminder of his own financial failure—was a formative event in de Beauvoir's life, and a source of real bitterness for her; I was impressed, however, at how impartial she manages to be toward her father himself, while coming to reject the set of values he held.

As with all other aspects of the book, her observations on gender relations are detailed and perceptive, and the roots of her feminism run through this volume, from her examination of the sexual double-standard that allowed her parents to entertain men who kept mistresses but not the mistresses themselves; to the assertion of her otherwise avant-garde philospher friends that they "can't respect an unmarried woman"; to the effects of having her reading censored (it was considered dangerous for unmarried women to read about sex). I can't resist including this passage, in which a ten-year-old Simone is reacting to her priest's story about a young female parishioner who reads "bad books," loses her faith in God, and subsequently commits suicide:Ce que je comprenais le moins, c'est que la connaissance conduisît au désespoir. Le prédicateur n'avait pas dit que les mauvais livres peignaient la vie sous des couleurs fausses: en ce cas, il eût facilement balayé leurs mensonges; le drame de l'enfant qu'il avait échoué à sauver, c'est qu'elle avait découvert prématurément l'authentique visage de la réalité. De toute façon, me disais-je, un jour je la verrai moi aussi, face à face, et je n'en mourrai pas.

[What I understood least, was the idea that knowledge led to despair. The priest hadn't said that the bad books painted life in false colors: in that case, it would have been easy to brush aside their lies; the tragedy of the girl he had failed to save was that she had prematurely discovered the true face of reality. In any case, I said to myself, one day I'll see it too, face to face, and I won't die.]

This passage makes me feel like cheering. And de Beauvoir does not neglect to notice that men and boys were not considered so delicate as to kill themselves over premature exposure to a tawdry potboiler. Still, Mémoires d'une jeune fille rangée puts de Beauvoir's feminism in perspective: she may be most famous for The Second Sex, but she's primarily a humanist, interested in the modes of existence experienced by all humans, and by specific humans, regardless of gender.

I'll be honest: this is not the memoir for everyone. If you're not interested in philosophy and like a lot to "happen" in your books, it will probably seem hopelessly dry. De Beauvoir's adolescence involves all the arrogance and angst one might expect from a recently-secularized teen who went on to become a preeminent existentialist (hint: a lot). But even when she is recalling her most turbulent periods, the adult de Beauvoir maintains her incisive, perceptive, ever-so-faintly-amused voice. She doesn't take herself too seriously, but neither does she dismiss her experiences or manifest a false modesty. This balanced tone, combined with her stunning intelligence and existentialist insights, makes this volume easily one of my favorite reads of the year, if not of all time. -

En 2020 :

Quand j'étais petite je relisais toujours les mêmes livres, je me tannais pas; drôle que ça m'arrive tellement peu maintenant. Sauf pour le premier volume des mémoires de Simone, que je finis pour une troisième fois. Ce coup-ci, l'envie de faire quelque chose de grand, de devenir ce qu'on peut être me rend surtout mélancolique. Mais quel bonheur, quand même, de lire une vie intérieure aussi bien rendue -- immense, frétillante, lourde dans ses mauvais jours, poignante, progressivement tournée vers le dehors.

Qu'est-ce qui me frappe encore le plus? Les amitiés féminines, les contraintes de grandir fille, le poids des conventions & des attentes, l'horreur que m'inspire la perspective d'un mariage arrangé à dix-huit ans. Il y a de la nostalgie, mais très peu d'idéalisation du passé; ce qu'on sent que Beauvoir regrette, parfois, c'est la conscience de soi, solide & puissante, qu'elle avait enfant. Que l'image qu'elle se fait des autres se soit craquelée, surtout celle de sa famille, est cause d'une frustration triste, mais pas de regret. Découvrir la vie & les gens tels qu'ils sont vaut la peine qu'on s'accommode de certaines déceptions.

Parce que Beauvoir, dans le récit qu'elle fait d'elle-même, reste une créature d'absolu : elle veut connaître les choses comme elles le sont, peu importe ce que ça veut dire. Mais surtout, elle cherche ce qui déborde du quotidien & le sublime, elle souhaite construire une oeuvre qui soit tout à la fois une cause, une promesse & une vocation. Plus elle avance, & moins elle est intéressée à reproduire les modèles qui lui sont accessibles, & plus elle apprend à valoriser cette espèce de volonté difficile qui l'anime, qiu se heurte au monde mais ne s'émousse pas. À la relecture, je me disais, quelle chance malgré tout de ne pas pouvoir faire autrement qu'être soi-même.

(Sartre arrive juste à la fin mais me donne déjà envie de me péter la tête dans les murs; vais-je me rendre au deuxième volume?)

En 2011 :

Je sais pas par où commencer pour parler de ce livre.

J'avais lu Mémoires d'une jeune fille rangée il y a peut-être quoi, quatre-cinq ans? & j'en garde à peu près aucun souvenir. (Parfois je m'inquiète de l'état de ma mémoire.) Juste une vague impression d'avoir trouvé le livre intéressant.

Alors cette relecture-ci c'est mon plus grand argument en faveur de toutes les relectures du monde, parce que cette fois-ci j'ai trouvé tellement, tellement de choses dans ce récit autobiographique. Parfois avec une auto-dérision affectueuse, le plus souvent de façon très introspective, sur un ton contemplatif, Simone de Beauvoir raconte son enfance, sa famille, ses grandes histoires d'amitié & d'amour, mais surtout ses doutes & ses longues périodes d'abattement, ce chemin tortueux & solitaire qu'elle pris dans l'espoir de se forger elle-même. & c'est d'un suspense étrange mais agréable, d'attendre avec elle qu'elle devienne ce qu'on sait déjà qu'elle deviendra.

J'ai trouvé fascinant de voir une femme aussi intelligente, aussi incroyablement perspicace, se pencher sur sa propre vie, les vingt & une premières années de sa vie, & tenter d'expliquer sa propre genèse. & ça sans complaisance, sans essayer de dissimuler les situations ridicules ou faussement mélodramatiques dans lesquelles elle s'est empêtrée, tout ça avec une honnêteté émotionnelle qui, même enveloppée d'une certaine pudeur, malgré les omissions & les approximations, laisse l'impression que le témoignage est complet & aussi sincère qu'il peut l'être.

& c'est difficile d'en dire plus que ça, malgré mon enthousiasme, parce que c'est un livre qui se vit tellement de l'intérieur, qui est tellement axé sur la réflexion & l'apprentissage de la connaissance de soi -- impossible de mettre en mots tout ce à quoi j'ai pensé en le lisant.

Maintenant j'ai vraiment, vraiment très envie de lire les deux autres tomes de son autobiographie, La force de l'âge & La force des choses. Un projet pour cet été, peut-être! -

"مذكرات فتاة رصينة " هي مذكرات كتبتها سيمون دي بوفوار، تحكي فيها سيرتها الذاتية منذ الولادة لحين. تخرجها من السوربون و لقائها بسارتر ، من خلال يومياتها إستطاعت أن ترسم لنا بانوراما عن الحياة الفرنسية في بداية القرن الماضي .. في كثير من التفاصيل التي كانت ترويها ، كنت أجد تشابها كبيرا بين وضع المراة في فرنسا في القرن الماضي ووضعها حاليا في العا��م العربي .

سيمون تحكي كيف كان عليها أن تدرس كثيرا و تتحدى المجتمع الذي تعيش فيه لثبت ذاتها و تخرج من محيطها الذي ينظر إليها كبوجوازية صغيرة يجب آن تتزوج بعد حصولها على الباكلوريا أو الليسانس ..

لكن سيمون أكملت دراستها و حصلت على الماستر في الفلسفة ، و هناك ستتعرف على سارتر أبو الفلسفة الوجودية ..

ما فاجأني أيضا هو أنها بقيت عذراء و لم تجرب القبلة ، و لإنتهاء الرواية لم تحكي مشهدا جنسيا واحدا ، ثم التربية الصارمة التي تلقتها من الراهبات و من والديها اللذان كانا يمنعا عنها قراءة بعض الروايات تحت بنذ روايات إباحية ..

شدني إليها حبها للتعلم و إدمانها لقراء. الكتب ، لم يكن لديها الخيار ، إما أن تتزوج أو تتعلم كثيرا لتهرب من الحياة الرتيبة ، و هذا ما فعلته سيمون ،تعلمت و لأجل العلم فقط ..

أنا أيضا أرفض الزواج ، و لا أعرف لماذا ، لكني دائما أسأل نفسي ماذا بعد ؟ ثم لا أتخيل نفسي أقاسم غرفة مع أحد لأسمع شخيره ، لا أفهم لماذا علينا أن نربط مصيرنا الحر جدا بمصير أناس آخرين و أين يكون ذلك قرارا اختياريا .

تساؤلات سيمون كانت وجودية ، أعتقد أنها مثلت جيلا من البورجوازيين الفرنسيين الذين وجدوا تراكما فكريا فلسفيا أتاح لهم تطويره و طرح السؤال ، كان لابد من التغيير ، الوسط البورجوازي الفرنسي

سيمون ، سارتر ، كامو .. السوربون ، المدرسة العليا للإدارة ، باريس ، شوارعها ، حانات موبرناس ، و مونمارت .. حرب الجزائر ، الإحتلال الألماني لباريس ، الحرب العالمية الأولى .. كلها أشياء و أحداث جعلت من مذكرات سيمون شاهد على حقبة مهمة من تاريخ فرنسا و من تاريخ وجدان الفكر الفلسفي في شقه الوجودي . -

کتاب را برای بار دوم بود که می خواندم . وبسیار دقیق و موشکافانه سیمون دوبوار به شرح احساسات و تفکرات و وقایع که برایش پیش آمده پرداخته است

-

great great lifestory of a great great writer

-

I would crack between my teeth the candied shell of an artificial fruit, and a burst of light would illuminate my palate with a taste of blackcurrant or pineapple: all the colours, all the lights were mine, the gauzy scarves, the diamonds, the laces; I held the whole party in my mouth.

Living in Indiana, mass transit remains a topic left of center. Sure we have a bus system but nothing further. Such is dreams of those elites who want to undermine something core, something both pure and competitive: something FREE. I have nerded on trains most of my adult life and look forward to every opportunity to indulge such. That was before I was to spend a week commuting at peak times back and forth from Long Island to Penn Station. Thus my spirit has been tempered. I can say with relish that this memoir was definitively transportive. I was impressed with her specificity, the reliable old journal always helps to sort things out. The dutiful of the title is ironic. Her true obligations weren't filial but to a more harrowing tradition.

This is some arrogant reading. My eyes did tend to roll. That said, the candor at times was certainly to be admired. -

I have developed a crush on Simone. What an incredible woman. What a brain. Even from early childhood her intelligence shows. Her courage, her strength. I truly find her so interesting.

Also, at times, she made feel like a useless shit. I think of her struggles she had to go through to get her knowledge and independence and I have all of that for free and what have I done with my life?

But of course she also inspires a great deal.

I didn't know she was so religious actually, that came as a shock. I loved this book, a slow thinking-book. It will not be for everyone I guess. If you're not interested in philosophy and like a lot "to happen" in your books, it will probably seem a bit boring to you.

For me it was 5 star for sure. And I look forward to read more from her. -

” Il fatto è che avevo fatta una cocente scoperta:

la bella storia che era la mia vita,

diventava falsa a mano a mano che me la raccontavo.”

La memoria, si sa, non è mai oggettiva.

Lo stesso ricordo può assumere diverse sfumature e che sia colpa del tempo che passa e deforma oppure del momento stesso in cui accade un episodio della vita e lo viviamo ognuno in maniera differente, beh, poco importa.

Ogni volta che decido di leggere un autobiografia sono, quindi, conscia del fatto che sto per guardare ciò che chi scrive ha deciso di farmi vedere.

E’ come se si stabilisse un patto tra autore/autrice e lettore/lettrice:

chi scrive inquadra l’immagine che vuole mettere in risalto,

chi legge ammette il proprio voyerismo giustificandolo per passione intellettuale e ne accetta i silenzi.

Dico subito che queste memorie di Simone de Beauvoir non mi hanno particolarmente colpita.

Il fatto è che il contesto di queste memorie �� ad una distanza siderale dal mio vissuto.

Non solo perché sono nata settant’anni dopo, non solo perché sono italiana e non francese ma soprattutto per il contesto famigliare di alta borghesia conservatrice.

Un’infanzia, quella di Simone, in cui è continuamente vezzeggiata ed un’adolescenza con turbamenti, ansie ed insicurezze come da manuale.

Ciò che è più interessante è la crescita intellettuale:

stimolata dal padre già dai primi anni ma coltivata egregiamente grazie ad un’indole assolutamente famelica nei confronti del sapere.

Una brava bambina che la famiglia e la società vogliono sia una ragazza perbene:

”...io mi rifiutavo, con la stessa ostinazione di quando avevo cinque anni, a prestarmi alle commedie degli adulti.”

L’amore, l’amicizia con tutti i rimescolamenti del caso non sono il punto focale di queste pagine che va, piuttosto, rintracciato nelle connessioni con il pensiero intellettuale di una generazione che si affacciava allora sul primo dopoguerra schifata dall’oppressiva mentalità reazionaria.

Gide, Valery, Claudel, Proust.

Questi i punti di riferimento, le prima fondamenta del pensiero rivoluzionario:

” Borghesi come me, si sentivano come me a disagio nella loro pelle.

La guerra aveva distrutto la loro sicurezza senza strapparli alla loro classe; si rivoltavano, ma soltanto contro i loro genitori, contro la famiglia e la tradizione.

Nauseati «dell’imbottimento dei crani» cui erano stati sottoposti durante la guerra, reclamavano il diritto di guardar le cose in faccia e di chiamarle col loro nome; solo, poiché non avevano alcuna intenzione di far crollare la società, si limitavano a studiare con minuzia i loro stati d’animo: predicavano la «sincerità verso se stessi».

Respingendo i clichés e i luoghi comuni, rifiutavano con disprezzo le vecchie dottrine di cui avevano constatato il fallimento, ma non tentavano di costruirne un’altra; preferivano affermare che non bisogna mai accontentarsi di niente: esaltavano l’inquietudine.”

Simone ci racconta da dove arriva ma, soprattutto, dove va.

E uno sguardo su un ambiente dove paletti e confini sono solide barriere che durante l’infanzia danno sicurezza ma crescendo ed acquistando coscienza sono pericolosi confini da abbattere.

(Mi è rimasto tra le mani un altro libro

Le Grand Meaulnes) -

Well written discourses on growing up are amazing. The clarity with which the author described her years from infancy to childhood and beyond was astonishing; it was as if the babies in Mary Poppins had retained the eloquent speech which they used to discourse with birds and other nonhuman entities. It made for some serious misunderstandings on my part at the beginning though, as I was originally very annoyed with Simone at the beginning of her life. Her tantrums and her taking of her blessed life for granted were very frustrating, at least until I realized that the way she was conveying her emotions and thought processes made her seem much older than she actually was. It was easier to forgive her then, and actually made the reasons behind her outbursts as a child fascinating instead of insufferable.

Once my annoyances with her cleared up, her life was one of the more intellectually stimulating autobiographies that I have had the pleasure of reading, to the extent that I will have to find more works by the deep thinkers of the period. I'm especially looking forward to reading Jean-Paul Sartre; the way she describes him makes me wish I had met him, and if given the chance I would gladly give my right arm in order to do so.

Many of the people she interacted with were interesting, but what shone clearest through her time with them is how it was normal for her to quickly fall in with them, discourse for a while, and then fall out just as quickly. This resonated deeply with my own experiences with others, along with the fact that she had multiple periods of stagnancy that overwhelmed her body and soul. To want for everything, yet be limited to a repeating daily life barred on all sides by both physical walls and ignorant people! There is no greater torture than this. Reading this book doesn't help my own dissatisfaction with my short term goal of settling down to a career, but it was satisfying in my long term goal of figuring out exactly what my existence is supposed to consist of.

I think there's a little too much personal reflection in here. Darn. Going back to the book, it was a heady mix of descriptive elegance and intellectual stimulation in a never ending journey of self-discovery, and Simone honed the process of its creation down to a science. Not sure if I'll ever look into any of the books that she devoured in the course of the novel, but as said previously, I definitely need to read Sartre. Someone who was described as always thinking definitely deserves some attention.