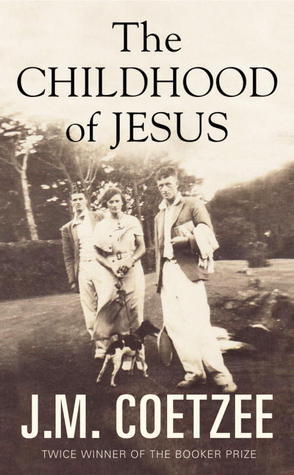

| Title | : | The Childhood of Jesus |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1846557267 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781846557262 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 288 |

| Publication | : | First published March 7, 2013 |

| Awards | : | Metų verstinė knyga (2014) |

Simón finds a job in a grain wharf. The work is unfamiliar and backbreaking, but he soon warms to his stevedore comrades, who during breaks conduct philosophical dialogues on the dignity of labour, and generally take him to their hearts.

Now he must set about his task of locating the boy’s mother. Though like everyone else who arrives in this new country he seems to be washed clean of all traces of memory, he is convinced he will know her when he sees her. And indeed, while walking with the boy in the countryside Simón catches sight of a woman he is certain is the mother, and persuades her to assume the role.

David's new mother comes to realise that he is an exceptional child, a bright, dreamy boy with highly unusual ideas about the world. But the school authorities detect a rebellious streak in him and insist he be sent to a special school far away. His mother refuses to yield him up, and it is Simón who must drive the car as the trio flees across the mountains.

The Childhood of Jesus Reviews

-

I am not much given to write book reviews because, as the saying goes, birds do not make good ornithologists. But with the publication of J. M. Coetzee's latest novel, The Childhood of Jesus (Harvill Secker, London; Viking, New York) I am moved to address the issue of reader engagement or, shall we say, responsibility. That responsibility begins by reading a work of fiction on its own terms. That is, with an open mind. Professional reviewers have been put off by the apparent strangeness of this novel, but I sometimes think it is the job of such people to be put off, to find fault, to interpret beyond their means to justify their existence. But … what about the reader? When one buys a book it would seem that one is entering into contract with one's self and with the author; a contract of respect for the intelligences involved on both sides. Scanning the commentaries of amazon.com buyers, I made a list of some of the titles these individuals gave their reviews: funny little book; more of the same; a strange land and a slow read; searching for utopia; a hollow egg and, my personal favorite, well crafted, but unfathomable and at times tedious. Of course, for a book to be unfathomable -if by that one means profound, immeasurable, enigmatic- it must, by force, be well crafted. Reading each of these "reviews" what was immediately evident, to me, was the unwillingness of the readers to be challenged beyond the easy and the conventional, the sentimental, the entertaining, the expected.

I have been reading Coetzee since he became internationally known with the publication of his third novel Waiting for the barbarians. I was very young and filled with ideas of how the world should be. That novel was painful to read, but the stark beauty of its prose, which I have never forgotten, indicated that indeed there was beauty above and beyond the cruelty depicted within its pages. That beauty was Truth. Echoing Beckett's vision of life with no consolation, no dignity, no promise of grace, Coetzee has written that, in the face of it all, the only duty we have is "not to lie to ourselves." Truth is beauty. With each successive book Coetzee has maintained that line, expanded the search for Truth. In my experience, not a single one of his books has been "more of the same," and never "a hollow egg."

So we come to The Childhood of Jesus. A man and a small boy have arrived at Novilla after an apparently perilous journey during which the boy has "lost" his mother. Novilla, a Spanish land devoid of all possible amenities, where politeness abounds but friendliness is negligible, it is the land one arrives at after everywhere else has, apparently, failed. In its anodyne reality Novilla is neither utopia nor dystopia; it is more like living inside one's smart phone. Once there, you are expected to clean yourself of memories and take on new names. The man and the boy are given the names Simón and David, respectively. Simón is very caring and paternal with David, but he never ceases to proclaim that the boy is "not my grandson, not my son. We are not related … the boy happens to be in my care." Here we realize that the title of the novel is not misleading, for it serves to put the narrative in context. Simón is, like Joseph was to Jesus, a putative father. The man's sole purpose is to find the boy's "true mother" but he has no methodical or logical plan to find her, believing that he will know who she is once he sets eyes on her. Perhaps that was how the angel announced itself to Mary, too.

And so it goes that, one day, they happen upon the gates of a wealthier gated community known as La Residencia, where they spot a thirtysomething woman playing tennis with two men. Simón "recognizes" her as David's mother. The woman is named Inés, she leaves La Residencia and moves into the gray flat where Simón and David are sheltered, and starts acting as the boy's overprotective mother, quickly revealing her inexperience but nonetheless remaining steadfast in her maternal mission. If this sounds absurd, let us remember again the title of the novel and recognize that the concept of the immaculate conception is no less incongruous.

For his part, David swings back and forth between iconoclastic child genius and brat. The story ends as Simón, Inés and David flee from Novilla in the wake of a judicial order to consign the boy to a reformatory, the image of the flight to Egypt not even delicately disguised if it were not for –speaking of disguises- David being dressed up in a magician's cape too large for his boyish size, and wearing sunglasses after partially having blinded himself in some sort of alchemical diversion. Although the coat is not specified as being of many colors, I could not avoid the image of the son of Jacob and Rachel, Book of Genesis, as re-hatched for modern pop culture by Andrew Lloyd-Webber in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream. After all, the Bible offers an explanation for the name Yosef: first it is compared to the word asaf from the root "to be taken away" and combined with the root word ysp, meaning "to add." This may be a stretch of my reader's interpretation, but I have a feeling Coetzee would derive quite a chuckle from it without denying me my reading which, after all, is firmly in the context offered by the title. Simón, Inés and David then meet a couple of people on the road, whom they invite to join them on their journey to an unimagined new life. It hardly seems worthwhile, the effort, the journey to a new place whose only promise is … a continuation of the same. … il faut continuer, je ne peux pas, je vais continuer … so ends Samuel Beckett's L'innommable. Only in Coetzee's vision everyone gets a name.

But biblical absurdities are not the only things evoked in this novel. The first of Coetzee's Australian novels, Elizabeth Costello, featured a broad correspondence between philosophers. In The Childhood of Jesus the author ups the ante, the philosophical musings and quotations are integrated into the narrative. It should be said here that, shortly after arrival at Novilla Simón finds work as a stevedore in the docks where, during breaks, he and his colleagues discuss the nature of life. When Álvaro, the unbelievably affable foreman, questions " … the thing itself … do you think remains forever itself, unchanging? No. Everything flows … you cannot step twice into the same waters." I at once thought of Parmenides, searched in vain until Jacqueline de Romilly's La Grèce Antique elucidated me that it was (of course!) Heraclitus. Well … at least I was within the pre-Socratic ball park. And what are Socrates and the pres doing here? Well, Nietzsche did not like the way European philosophy had ensconced the hemlocked master at its center, so he offered Jesus as an alternative. And the plus points of these alternatives are healthily discussed in the dockside agora of our stevedores. Digressions? No, incursions into the heart of this very complex and stimulating novel.

John Coetzee loves to let the reader create, make, his or her own sense out of his novels. Is Novilla a Dantesque vision of the afterlife? Is it a Socratic/Platonic utopia? Does it deliberately spoof biblical clichés? Perhaps all of the above, perhaps none. Gertrude Stein, on her deathbed, is reputed to have asked "What is the answer?" When no reply came from Alice B. Toklas she said "In that case, What is the question?" I love novels that leave me to ruminate on its possible clues and answers. It is the author bringing in the reader to take part in his creation. -

J.M. Coetzee și-ar fi dorit să publice Copilăria lui Isus cu o copertă imaculată, fără nici un titlu vizibil, doar cu numele J.M. Coetzee tronînd suveran într-un dreptunghi alb. În opinia mea, era suficient. Nu s-a putut. În industria cărții nu există acest obicei, cărțile trebuie să poarte un titlu.

Ar fi fost suficient și dintr-un alt motiv. Orice titlu, oricît de vag și imprecis, oferă și, adeseori, impune (prin el însuși) o cheie de lectură. Chiar și titlul lui Ionesco, Cîntăreața cheală...

Firește, cînd citești titlul Copilăria lui Isus, te gîndești obligatoriu la Iisus Christos și începi, aproape fără să vrei, să cauți referințe la personajul evanghelic. Și, din păcate, le găsești din abundență, aluzii sînt / par a fi peste tot, nu pentru că ar fi fost puse acolo de Coetzee, nu mai era necesar (titlul e suficient), ci fiindcă începi să le găsești spontan, tu, cititorul lui Coetzee, care posezi o cultură creștină și ai citit atît evangheliile canonice cît și pe cele apocrife (inclusiv Evanghelia lui Nicodim). Titlul ne „ghidează” cu exigentă blîndețe: vedem în el un soi de rezumat al cărții (în vechime, titlul chiar era un rezumat, o descriere a conținutului unei cărți) și o expresie a „intenției” autorului.

Literal privind lucrurile, cartea prezintă o societate ciudată (foarte asemănătoare cu aceea din Castelul lui Kafka), în care lumea este perfect mulțumită cu cît are (id est cu puțin). Indivizii par a pune în practică una din sentențele lui Seneca: „Sărac nu este cel care are puțin, sărac este cel care vrea mai mult”. Singurii oameni care vor mai mult și vor altceva decît ceilalți sînt Simon și David, unchiul și nepotul, cum ar veni, deși cei doi nu sînt rude. În al doilea rînd, tot literal privind lucrurile, ficțiunea lui Coetzee descrie un an sau doi din copilăria unui copil înzestrat, isteț, dar cam exaltat și, uneori, mitoman.

Aluziile la biografia lui Iisus sînt destul de multe și, pentru mine, evidente. Dar sînt aievea în text sau, de fapt, cititorul găsește acolo exact ceea ce caută, tocmai fiindcă titlul îl îmbie să caute în acest sens? Sînt intenționate sau numai ironice? Nu știu. Și nici nu vreau, deocamdată, să-mi bat capul cu asta.

Mi se pare mai important să subliniez afinitatea de structură dintre cartea lui Coetzee și aceea, amintită mai sus, Das Schloss, a lui Kafka. Un individ (K. sau Simon) ajunge într-un oraș, Novilla (aici), într-un sat (în Castelul), și descoperă că oamenii au un mod curios, uniform, mediocru de a gîndi: nu le trece prin cap că legile pot fi încălcate, că pot exista pasiuni (iubirea, de pildă) și că ar putea trăi altfel. Individul (K. / Simon) încearcă să se adapteze la această „viață nouă” și nu reușește. Rămîne un intrus, o excepție. Este un inadaptat.

În Copilăria lui Isus, intrusul este însoțit de un copil, pe nume David, el însuși rebel. Ce se întîmplă în acest caz? Ca să vedeți ce urmează, citiți cartea lui J. M. Coetzee...

https://valeriugherghel.blogspot.com/ -

جون ماكسويل كوتزي من أهم الكُتاب المميزين في الفكر والأسلوب

الرواية امتداد لأعماله التي ترسم فلسفة ورؤية حياتية وفكرية

يصل رجل وبصحبته طفل لاجئين من مكان ما إلى مدينة نوفيلا

يومياتهم ومحاولاتهم في التعايش والتأقلم مع الحياة الجديدة

لا يكشف كوتزي عن هوية الأشخاص والأماكن, لكن المدينة يغلُب عليها الطابع الاشتراكي

يبدو الاختلاف بين الرجل الأربعيني سيمون الذي يُمثل الفردية بكل خصوصيتها من أحلام وأفكار ورغبات في المتعة والتغيير

وبين أصدقاؤه ورفاق العمل في المدينة المتطابقين تقريبا في إطار عام في التفكير والمعيشة

فيه شيء من الغموض في الحكي عن ديفيد, الطفل المختلف الذي يبحث عن قدراته الخاصة في عالم خيالي بدون قيود

وأيضا في الربط الرمزي مع عنوان الرواية

الحوار ممتع باختلاف موضوعاته, يطرح التساؤلات والرؤى المختلفة للحياة, ويبحث في الطبائع والمعتقدات والمعاني

السرد سلس والترجمة ممتازة للشاعر والمترجم عبد المقصود عبد الكريم -

This was my first Coetzee for several years - the last new one I read was

Diary of a Bad Year, and at that time his new books seemed very gloomy and introspective. So thanks are due to the 21st Century Literature group for selecting this as one of this month's group reads.

This one seems on the surface to be a simple fable. Simon has arrived in a Spanish-speaking country across the ocean and is accompanied by a small boy David who has lost his parents and his identity documents at sea. It is soon apparent that the society they have arrived in is some form of utopian community, where new arrivals are expected to forget the past, and simple lifestyles involving manual labour, limited diet and philosophical education are favoured. Simon has told David they will find his mother, and they do find a woman (Inez) willing to play the role. David is a form of idiot savant - he is resistant to conventional education and appears to be living in a fantasy world, but succeeds in teaching himself to read using a children's illustrated Don Quixote. The state wants to educate him in a special school, and Inez and Simon attempt to resist this.

The setup seems to be a way to allow Coetzee to discuss his ideas of what it means to be human, and what a society can and cannot provide. Religion is curiously absent, and the relevance of Jesus seems distant and oblique.

A superficially easy read, but one with plenty of hidden depths, deeper significance and ideas to ponder. -

We have all felt that exalted state when a writer seems to write specifically for us. That is part of why I read, I am an exalted state junkie. J.M. Coetzee has been that for me. He took particular care through, Elizabeth Costello, Slow Man, Diary of a Bad Year, to carve these particular novels to my taste. Even books of his that I didn't like, I liked due to the elegance of his authorial voice. So, when, The Childhood of Jesus arrived from amazon, since my hands tend to shake a little, I asked my wife to open the box so the book's jacket would not be damaged. A successful cardboard birthing took place before my eyes. Then, the intrigue of learning the binding's etiquette of range. I opened it slowly, tensing, finding where to stop before the calamitous crack -sound. A slight riffle of the pages, then I picked up the scent of the paper, the print. This is the enclave of the spiritual, as it should be.

I immediately marveled at how the master set himself a novelistic task to wind himself out of that which Houdini might shrink from. This is what great authors do, set themselves a challenge from the onset. There is no queasy looking down from the heights, no timid hesitations. A man, a young boy separated from his mother, are rescued from the same damaged ship and arrive at an unnamed country. Feeling responsible for the poor boy the man begins a long quest to find the boy's mother. Finding work at the docks we quickly see the title's sophomoric set-up of Jesus and the apostles, as well as other references, and can quickly jump past this intentional quirk to the meat of the narrative.

I found but two problems: there was no meat nor any significant narrative. Coetzee made it clear early on the impossibility of finding the mother under these chaotic and harrowing circumstances. He gave no warning of the implausibility which he planned to reckon on me, who already unwittingly slightly, somewhat, cracked the binding, of the finding of a substitute mother for the boy as well as most events about to be plummeted onto the page.

Being a Coetzee co-dependent I reshuffled the deck of cards and proclaimed his intent as a poking of fun at the typical narrative stratagems like building an internal structure so when an event occurs its plausibility is unquestioned, unnoticed, and the story flows to its further tributaries, we readers riding the crest of the unfurling wave. Returning to my Coetzee co-dependent support group I left the meeting-I was the only attendee-saying, NO. The foundation of the story was not set, the bones left bare. I f you really want to know what I am trying to describe go to; Nathan N.R. Gaddis's review of Baktin's, The Dialogic Imagination, and scroll down to the section; Things That Look Like Novels. Our own N.R. takes dense and difficult material planing it down to its essence. If only Coetzee read this first.

What to make of this? There was for me no magic of his authorial voice, no meaning eventually rising from the prose, the polished language, to overcome plot difficulties. Was this a mis-step, uncalibrated? Is it the ending throes of the material which spurred his style and left me nestled within the brilliance of his mind? I vote for a mis-step. I hope that is all that happened.

-

“David is no ordinary boy. Believe me, I have watched him.”

I’ve never read anything quite like The Childhood of Jesus, recommended to me by my friend G for several years. J. M. Coetzee was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2003, after having won two Man Booker Prizes, one in 1983 for The Life and Times of Michael K, and in 1999 for Disgrace, though I think his real masterpiece is Waiting for the Barbarians. There’s an allegorical quality for that book, and this is also so for The Childhood of Jesus (the first of a trilogy), though the tone is very different than in Barbarians.

The story is of an older (late-middle-aged?) man, Simon who, on a refugee ship, takes under his wing a young boy of five, David, who has apparently become separated from his parents. They meet Elena and Ines; Simon gets a job as a stevedore. I should say that this book is not really historical fiction about Jesus (of Nazareth), oddly enough, in spite of the title. Jesus is never mentioned; nor is religion, though spirituality is a central concern of the book, and I think we are led to consider David--which means “beloved of God” as resonating with the life of Jesus in ways, some of them playful, fanciful, cryptic, thoughtful:

*When they arrive in their new country, David asks “what are we here for?” as in the meaning of life.

*David’s parentage is in question, as with Jesus (virgin birth? Joseph? Son of God?)

*There’s a lot of philosophizing in this book (as in The Bible), specifically ideas about ethics, morality, with respect to relationships, such as parenting, the meaning of work, and so on.

*David is a pacifist, non-violent, (though he learns to read and write largely on his own--a kind of savant--by reading a children’s illustrated version of Don Quixote, who was intent of rescuing folks in distress while brandishing a sword)

*David says that he wants to save people--“I’m going to be a lifesaver;” he says he is an escape artist (as in the Lazarus story, or Jesus leaving his tomb after the Crucifixion). He says he wants to be a magician, too (water into wine might be seen by some as magic, though others will call this a miracle).

*Ines, David’s adoptive mother, calls David “the light of my life” as Jesus is sometimes referred to in The Bible

Some interesting aspects of the book:

*The specific country where all our refugees arrived is not specified, though they have to learn Spanish to live there. Where they came from and where they now are is not an important detail.

*Another kind of allegorical or fantasy element is that they all seem to have lost their memories of their former country or countries. No explanation for that. So it’s a refugee story, where the past has to fade to assimilate in some respects into a new country or culture. Jesus was born on the road, in Bethlehem, and through his life he moves around, as David seems to do.

*Numbers--mathematics, the philosophy of mathematics--figures in the book. Coetzee got degrees in both literature and mathematics. Most people’s understanding of math is that it is rational, objective: 2+2=4, but David thinks that numbers are not like that at all. Even the initially more conservative Simon comes to see that there may be ways to see that under some conditions 2+2 may equal 5, or whatever. In other words, rationality and objectivity are not necessarily the standard for knowledge and wisdom in the universe. This comes out in a consideration of David’s resistance to traditional schooling and what counts as “preparation” for life. David is a child of imagination and stories. A doctor advises Simon and Ines:

“As for his being special, let us set that question aside for the moment. Instead, let us all, the three of us, make an effort to see the world through his eyes, without imposing on him our ways of seeing the world.” Yes! If we could do that more in schools!

Overall, I think the book is an allegorical novel, a philosophical novel, not in many ways "realistic fiction" in a conventional sense. Much of the talk seems in some ways heightened, alwasy about ideas. The main ideas here seem to be about the struggle between a view of ethics as either one of rules and laws vs. one of spirit. Simon begins as a rules guy, and he remains principally a rationalist, but he begins to see the world through David’s spirit. It was very strange to read, but I took my sweet time with it. I see at a glance that a lot of people seem to have been bored with it, really hate it, and I get that--I have had to warm to it, and it's not at all a warm book--but I am liking it. That I am thinking about it all the time means something to me. -

He sits down to create another world. He takes the real world and strips it of all the things that are not required just as he has stripped language of all that is not required, just as he has stripped narrative technique down to third-person I-narrators, even in his own diaries.

We are left with the bones of narrative, the bones of language, the bones of a world. The reduction is clever. For instance, to reduce language even further, we must know that all the characters conduct their (partly highly philosophical) conversations in Spanish and that Spanish is not their first language, but the lingua franca this new state at which they have arrived forces on them. And this world in which people are assigned new Spanish names and asked to forget their past (which they all seem to achieve easily - is there supernatural help in this?), this world where stevedores are philosophers and everybody is just about helpful, but no more, is not enough for David, the Jesus of the title ("Yo soy la verdad.", p. 225). He wants to find a new world, eventually they travel to Estrellita del Norte and in true Jesus-manner, David invites all and sundry to abandon their lives and come join him.

One is greatly looking forward to the scholars who will name the analogies - is Mr Daga Satan, tempting Jesus with his toy and wild ways? Who do Inés' brothers stand for? Why does Inés receive David through Simón, as it were? That is not how we read it in the bible - and it would have been easy to make her conceive without knowledge of the father, surely? And Bolívar the dog? How does he fit into the picture?

The novel leaves many issues unanswered - in the best possible way. The most intriguing question for this reader is how we must cope with this Jesus who comes across as a spoilt brat, who hurts people and is utterly unreasonable, but always convinces those around him that he is indeed special. -

The right to be different

To be absolutely clear: this is not a religious book, it isn't even about Jesus. On the contrary, this rather is a very disturbing novel, I would call it a dystopia.

For starters there’s the setting: a vague country, where people arrive by boat, as refugees, "washed clean" of their past. The main characters, the older man Simon and the little David (the boy he took care of during the boat trip), are such refugees. The order in the new country is consciously left impersonal and invisible, but there are clear laws, such as social differentiation (beautiful residential neighborhoods, poor social neighborhoods, refugee camps, etc.) and a very bureaucratic culture where the rules of what is right and what not are omnipresent (very Kafkaian). The people in this country compensate for this by a striking attitude of "benevolence" towards each other and towards the existing order: everyone behaves neatly, even to a certain extent helps others, but without warmth, without feeling, as from an obvious duty.

Simon and David expose this benevolence culture and go against the tide. In the first part of the novel Simon continually questions the fundaments of the social order. In fact, he stands for the passionate man, who wants more than formal contact, respect, and benevolence; and he always craves for more both intellectually, emotionally, sexually and even in the labour process; and he passionately pleads for the individual's right to want more. But with that he clashes with the benevolent indifference of the officials he comes in contact with, with his fellow dock workers, and with his neighbours in the barracks assigned to him.

To me, the Simon figure is the most captivating figure of this intriguing novel. He is perhaps a bit tedious and paternalistic, but he is also a kind of a Socrate, "a louse in the fur" that drives everyone around him to improbable philosophical conversations. With his fellow dock workers, for example, he talks about good and evil, progress and the meaning of labor, the idea of justice and the elusiveness of history. In these discussions the others accept the natural obviousness of the existing order as a reasonable, rational organization, but Simon doesn't agree.

And then there is the little David, who - in his own way - also challenges the existing order; but he's a character that we, as the reader, barely get a grip on. Sometimes he is an angelic boy who charmes people, but he can also be a son of bitch who stubbornly locks into his own imagination and always wants to be right. For instance, he has his own system of reading, writing and arithmetic, which of course causes him to clash with the school where he is going.

I do not know what to think of this guy, and I think this is intended by Coetzee. Of course, because of that title, you constantly ask yourself: is David an alternative Jesus? And Coetzee cunningly gives small indications to justify that identification: the name of foster father Simon, is a clear reference to Simon-Peter (the most important disciple of Jesus), David’s foster mother Ines is a virgin who always wears blue, and together they form a kind of saint family who flees at the end of the novel. And also the dead horse that, according to David, can become alive again after 3 days is a clear reference to the Christ story, etc. But on many occasions, in the novel, David is just presented as an insatiable spoiled child.

Some (see the review by Vincent Blok on Goodreads

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...) propose a way of reading this novel in which David stands for the singularity that opposes the universal, the individual that opposes the rational organization of society, and demands the right to its own perspective and experience. In this sense he is in line with the portrait I sketched of the older Simon. And there is something to be said for that. With this novel Coetzee would thus offer us a critical view on our culture, which suggests that in our overordered and hyper-rationalist society there apparently is no place for deviant opinions and other ways of living. And that is certainly a relevant message.

I must say that I am not fully convinced. The thesis certainly stands for the first half of the novel, especially because of the stubborn, often very philosophically charged questions that Simon continually asks. But with the whole fuss about the little David in the second half of the novel, Coetzee goes a step further. It seems as if we are going from a Kafkaian atmosphere into a more surreal, beckettian environment. Because of this transition even the stubborn Simon is forced into a defensive role, when he tries to teach David the basic principles of interaction between people, and demonstrates the need for transparent rules for reading, writing and arithmetic. David continues to stubbornly reject it, and that makes it hard to follow his logic.

At the end of the novel, old Simon seems to offer us a key by moving into David's mind, "But what if we are wrong and he is right?" He says to his colleague Eugenio. "Suppose this boy is the only one who really sees through it?" It is clear that Coetzee wants to get us out of our comfort zone with this contradiction. And he certainly succeeded in that. It makes me very curious about the next part

The Schooldays of Jesus. -

Jėzau, kiek čia visko.

Berniuko vardas Dovydas, bet tai nėra jo tikras vardas. Jis gali būti vardu Jėzus. Kodėl gi ne. Nežinia kaip tapęs našlaičiu Dovydas atvyko į svetimą/kitą/nesavą kraštą su žmogumi vardu Simonas, kuris juo rūpinasi, kaip tėvas. Lyg "iš dangaus" jam nukrinta ir netikra mama, vardu Inesa (skaisti, šventa).

Bet knyga - juk ne apie Jėz��. Ar, visgi, ir apie jį?

Man ji buvo apie keitimąsi, (ne)prisitaikymą, užmarštį/atmintį, kitoniškumą, amžiną kartų nesusikalbėjimą, apie migraciją.

Dar daug man klaustukų šioje knygoje.

Nekantrauju pradėt antrą šios trilogijos dalį. Nors ir skubėt nesinori... -

A hollow egg...

When I was young, Easter eggs were a double treat. There was milk chocolate on the outside and then, when the egg was opened, there was an extra something inside, a small packet of Maltesers, Chocolate Buttons or, for the really lucky, Smarties. (Of course, note well that the Easter egg was also an allusion to the story of Christ.) What Coetzee has given us here is a hollow egg – and one that is, like this introduction, candy-coated with a thick layer of contrived and unsubtle symbolism and allusion.

The book is set in an unnamed society, where immigrants arrive with all memory of their past wiped clean and with new names given to them by the authorities. So we start with the arrival of Simon and the child of an unknown father, David (yes, David. Jesus only puts in an appearance through our friend Allusion). The society is a simple one where money is plentiful but food is in short supply. In fact, for the first couple of weeks, Simon and David are forced to live by bread alone – a thing Simon really feels man cannot do. However, the people of this new society are full of goodwill towards each other and happy with their lot – along with the cricket-bat-over-the-head Christian symbolism, Coetzee’s society seems to draw heavily from Huxley’s Brave New World, with Simon playing a very civilised and philosophical John the Savage.

Simon has taken responsibility for finding David’s mother in this new world – a task that seems impossible since not only do they not know her name or what she looks like, they also don’t know David’s real name (symbolic, eh?). Nothing daunted, Simon decides that a woman he has just met is David’s real mother and persuades her to accept him as her son. She is, of course, a virgin. David, we are told repeatedly, is an exceptional child though in what way is unclear – those who love him accept his exceptionalism without question, one might say on faith, while the authorities soon come to believe he is disruptive and must be contained.

The real problem with the book is that the symbolism is crashingly unsubtle, crammed into every nook and cranny, and yet ultimately signifies nothing. By half way through I was actually beginning to count the references – bread, tick; fishes, tick; wine, tick; virgin mother, tick; raising from the dead, tick; resurrection after 3 days, tick. At one point, as David watches Mickey Mouse on TV, Mickey’s dog is referred to as Plato. By that stage, I no longer knew whether this was typo, error or mysterious allusion, but sadly I suspect the latter. There is also a real feeling of misogyny throughout the book, with the women being treated as not much more than walking wombs or repositories for Simon’s (largely unfulfilled) sexual urges; though since I haven’t read anything else by Coetzee, I couldn’t decide if this reflected the author’s own outlook, or whether it was again symbolic, perhaps of the male domination of the early Christian story.

Despite all of the above, Coetzee’s sparse writing style and use of language make the book a strangely compelling read and Simon in particular is an interesting character, if a little too caricatured as The Thinker. The possibility exists throughout that the book might turn into something wonderful, that the author might pull the mass of symbolism into something profound and meaningful in the end. But once the smooth and velvety chocolate of the prose has been savoured, there’s nothing inside and the hollowness of the egg left this reader feeling unsatisfied and somewhat cheated. -

A man and a small boy cross the ocean and reach a land where life has to begin anew -- getting new identities, learning a new language, adjusting to a new existence, and so on. On the way, they are washed clean of their past, old ties, and memories, perhaps to facilitate their acquiescence to this new life. This strange world is theoretically ideal, a land of conformity, reason, goodwill, temperance, and dutiful brotherhood where the immigrants have become accustomed to moderation of the senses -- greed, hunger, desire, lust. There are no fights, only philosophical disagreements devoid of any passion, untouched by animus. Not surprisingly, some of these themes of asceticism are espoused by Coetzee in his autobiographical trilogy, Scenes from Provincial Life, in particular vegetarianism, austerity, restrained passions, and the dignity in manual labour. Coetzee's protagonists, the aging, passionate Simón and the imaginative and gifted young David find it hard to resign to the insipid, stifling harmony of this parallel universe. And in a way, Coetzee questions his own beliefs by creating a rational, utopian existence which suffers from its own blandness -- an absence of desire and impulses, a saltless fare unable to satisfy an ordinary human appetite.

Because we all want more than is due to us. That's human nature. Because we want more than we are worth.

My Biblical knowledge is inadequate for all practical (and theoretical) purposes, but an allegory to the life of Jesus could be made here as David is an exceptional child, has a virginal mother, and beckons others to come with him to a new world. Not to mention, his fixation with saving others at the expense of everything else like his ideal Don Quixote, who sees things differently than everyone else -- a mighty combination of unrestricted imagination and reckless gallantry.

I'm yet again amazed by the economical and powerful writing and the weaving of philosophical threads through simple dialogue -- the characters are instruments for conducting philosophical discussions and the child, in his innocent curiosity, a vehicle of reflective inquiry. It may not rival the spare brilliance of his previous works and the second half of the novel might make you reserve your affections for more cogent narratives. In all honesty, I was hunting for clues on the workings of this abstract world so that I could establish if Simón and David were stuck in a strange afterlife, lost their memories to a rebirth or landed up in an austere version of our earthly abode as it was the only place available. My efforts proved inconsequential in the grand scheme of things as Coetzee deliberated the value of the personal (desire, love) over the universal (goodwill, benevolence) -- the identity of the unnamed land doesn't matter. What is meaningful is also abstract and its pursuit is a worthwhile quest. To quote Joyce, In the particular is contained the universal".

3.5 stars -

Bir distopya bu. Onu distopya kılansa herkesin aşırı iyi niyetli olması. Her şey olması gerektiği gibi, her şey kuralına göre işliyor, her şeyden yeterince var: Arzu nesneleri hariç. Arzulanabilir olanın resimden silindiği bir dünya anlatıyor Coetzee. İnsan kendini "ehlileştirmiş", dolayısıyla arzudan türeyenlere de yer yok bu evrende: şehvet, iştah, tutku, haz. Hiçbiri yok. Alın size distopya.

Öncelikle bu olağanüstü fikir karşısında bir saygı duruşunda duralım lütfen, hepimiz. Coetzee'nin kurduğu evrenin özünün bu olduğunu anladığım ilk sayfalarda vuruldum bu kitaba. "Kişisel olanın (arzu, aşk) evrensel olandan (iyi niyet, cömertlik) üstünlüğünde ısrar mı ediyorum? Eski ve konforlu olandan (kişisel) yeni ve tedirgin edici olana (evrensel) fazlasıyla geç geçişin bir parçası mı bunların hepsi?"

İsa Üçlemesi'nin bu ilk kitabında İsa'ya ve dine dair pek bir şey olmadığına dair yorumlar okumuştum başlamadan. Katılmadığımı söylemem lazım. Kitapta anlatılan çocuk David, koruyucusu Simon ve "anne"si Ines'in başından geçenlerde İsa peygamberin hayatından bildiğimiz pek çok anekdotu görebiliyoruz ama bence bu kitaptaki asıl dini gönderme tam da beni çarpan o yerden geliyor. Arzularımızı körüklemememiz, zapt etmemiz gerektiğini öğütleyen dinlerin istediği o dünyadayız! Fakat kitapta buna dair hiçbir şey söylemiyor Coetzee, din yok olmuş da, sonucu kalmış gibi. Ruhu elinden alınmış, makine gibi işleyen bir dünya bu.

Mültecilik, bürokrasi, kimlik, devlet, kanun gibi günümüzün temel gündemleri, bu kitabın da ana izleklerini oluşturuyor. Tam açıklanmayan bir sebeple bu "yeni dünya"ya göç eden bir çocuk ve adamın hikâyesini okuyoruz. Yeni dünya gelenleri kucaklıyor, ancak yalnızca yukarıda anlattığım şekilde.

Kitabın daha Kafkaesk diyebileceğim ilk yarısını olağanüstü buldum. Sonrasında gelen, çocuğun dünyayı sorgulamaya, kendi anlamını (ve felsefesini) bulma çabasına tanık olduğumuz bol diyaloglu ikinci bölümden ilk kısım kadar etkilenmedim. (Birisi Kafka'dan Beckett'e keskin bir geçiş yapmış Coetzee diye yazmıştı, o kadar doğru ki!)

Yine de bence çok iyi bir kitap bu. "İsa'nın Okul Günleri" ile üçlemeye devam şimdi. -

The best kind of parable is one that can convey its meaning through its simplest reading while harbouring depths into which the reader can dive deeper and deeper without ever reaching a hard and fast 'moral' at the bottom. For me, what makes 'The Childhood of Jesus' seem such a feat is the great complexity of thought it provokes through the telling of a relatively straight forward (but very moving) story, exploring ideas of morality without preaching or passing judgement.

The novel follows a boy, David, and his guardian, Simón's efforts to build a new life for themselves after seeking refuge in a country that is not their own. They have brought nothing with them from where they have come from, not even their names, and they know nothing of the customs and workings of their strange new home. While Simón and David's story resonates with the current political climate its also quite timeless, as Coetzee's allusion to the story of Jesus suggests. Along with a lack of chronological markers, although specified as Spanish speaking, the country that takes them is left geographically ambiguous and able to stand in for almost anywhere. Despite this abstraction, the characters and the setting remain vivid and engaging. The prose too was, unsurprisingly from the Nobel Laureate, starkly brilliant.

I was already an admirer of Coetzee, but this book convinced me of his genius. -

There are moments in this novel when I felt that perhaps, at last, something interesting might be said. But it was not to be. There is not a single original bone in its body. Trite, derivative and devoid of true depth. Imagine a Saramago novel with all of the genius sucked out. If this was by an unknown writer I may have stretched to two stars for some of the pages, but as I know what he is capable of, he gets one star and an F- in big red pen.

-

Sau: de ce nu te iubeşte lumea atunci când eşti altfel şi te răzvrăteşti împotriva regulilor ei.

Cartea asta e o surpriză incredibilă. Cred că m-am îndrăgostit iremediabil de Coetzee:

„Sperasem ca volumul să apara cu o copertă goală şi o pagină de titlu goală, pentru ca abia după lectura ultimei pagini cititorul să dea peste titlu, ”Copilăria lui Isus”. Dar în industria editorială, după cum se prezintă la ora actuală, aşa ceva nu este permis.“ (J. M. Coetzee) -

Well well well, what do we have here. Some sort of abstract allegory? A parable (or series of parables)? An anti-philosophy rant? A pro-philosophy rant? What is the nature of this book?, the book itself practically begs us to ask.

What is the nature of nature, what does it mean to live in this world, how do you live in this world. At times, the book seems to be a series of abstract, conceptual, philosophical conversations [1]. But there's a story, too: a strange, inexplicable story of a man (Simón), a woman (Inés), and a young boy (David) together "by chance", just trying to live and make sense of reality [2]. We, too, are trying to make sense of the world imagined in the book, and perhaps by extension our own world.

The characters speak "Spanish" (and have Spanish names [3]), but of course it is written in English (why Spanish?). Is it an English that sounds like it could have been translated from the Spanish? No, not really. Although the dialog does tend to sound "foreign", in that it's not really contemporary idiomatic English. Deliberate (on the part of Coetzee) of course, as we are in foreign territory here, a foreign reality it seems (at one point the boy sings something in German but he and Simón call it "English"). The world is not familiar at all, and yet also familiar in a strange, it-could-be-this-way way (why couldn't it? why shouldn't it?). We are caught off-guard, we are disoriented, disturbed perhaps (sometimes the way things work in the book's world are eerily similar to the way they work in Belgium [4]). What's going on here? [5] Is it post-apocalyptic, is it post-ironic (or post-anything)? Maybe it's avant-ironic? or is it neither, maybe it's off to the side, parallel. [6] The title is our only guide.

Who is Jesus? There is no mention of him in the book. [7] But the title invites us to see "Jesus" in the boy. The boy shuns violence (turns the other cheek), tries to "save" people from harm, is called a "gentle King", wants "brothers" (to start a Brotherhood), claims to possess magical abilities and the ability to read minds, writes at one point: "I am the truth" (225) So is it an attempt to imagine what the "childhood of Jesus" might have been like?

But maybe the real clue lies in Don Quixote (the reason for the Spanish?), which the boy takes a liking to and begins to read. Simón tells David that the author of the book is Benengeli (no mention of Cervantes, perhaps because the "spine is torn off" (151)). The boy thinks that Quixote is real, and of course he is real, because literature is real, just as Benengeli is as real as Cervantes. Simón says that Benengeli gave the book to the world, and that "therefore it belongs to all of us." (166) Also, David wants to go through the pages in a hurry because otherwise a "hole will open" (there is throughout the idea of holes, gaps, cracks, and (the fear of) falling). So maybe this book is necessary to fill in a hole, a literature hole, a small gap in the narrative of the world.

The style is dry (duh, it's Coetzee), and the book is not long, and yet there's so much there and something somehow manages to come out of it: heart, some kind of magic, the desire to desire, the will to live and start a new life.

[1] aesthetics, goodwill, work, nature, history, memory, logic, language, faith, death, life, etc.

[2] Simón wants a philosophy that "shakes you", changes your life. (238)

[3] Everyone has a name that's not really theirs. It's been given to them, just as they've been "forced" to learn Spanish.

[4] *cheeky wink*

[5] The book doesn't tell us, maybe because it doesn't "suffer from memories" (58).

[6] The paintings of Neo Rauch, which I happened to see while reading the book, are almost a visual representation of the disorienting what-world-is-this? feeling that comes from the book.

[7] Who is God? There is only one mention of God, at the end of the book. "But we don't live under the eye of God" (274). -

This had been sitting around on my shelves for years. I read the first chapter and then quickly skimmed the rest; I found it unutterably dull. It wouldn’t be fair of me to give a rating given that I barely glanced at the book, but I’ll just say that it would take me a lot of secondary source reading to try to understand what was going on here, and it’s not made me look forward to trying more from Coetzee (especially not the presumed sequel, The Schooldays of Jesus, from the Booker longlist).

Here are two passages I did quite like, though:I will bow my head to the force of the real. I will call it submitting to the verdict of history.

Children live in the present, not the past. Why not take your lead from them? Instead of waiting to be transfigured, why not try to be like a child again?

I won a copy in a Goodreads giveaway. -

Kol nepakeiti žiūros kampo, tai tiesiog dialektinis materializmas ar ateistinis egzistencializmas su reinkarnacijos galimybe, o kai pakeiti, gali išvysti ir kai ką daugiau. Pradžioje maniau, kad nepatiks. Klydau.

-

1.5 stars: The majority of this book is dialogue, which for me, makes it an easy read. The cover flap pronounced it as an allegorical tale. Given the title, I looked for the allegories of a spiritual journey. There’s much rhetoric on attachment, especially concerning memory and passion. There’s some philosophical debates involving the futility of existence. There’s some disputes about freedom of the individual versus what is good for the greater whole. Bland diets are suggested throughout the book to be the cure of all evils. The issue of true parentage is a theme throughout the novel. Listening to your inner voice versus seeing objective facts is another theme. To me, Coetzee started on some themes, and then just dropped them. There were threads of ideas that he partially pursued, and then left incomplete. This novel could have been interesting and fully allegorical. Instead, themes were left uncompleted, the reader left in a lurch. The ending, to this reader, proves it’s an incomplete novel. It’s a short book, easy to read, but I don’t recommend it; it’s very unsatisfying and unfulfilling. It’s like eating half an M & M.....

-

Проснувшись однажды утром после беспокойного сна, Магнус Миллз обнаружил, что он у себя в постели превратился во Франца Кафку. Лежа на панцирнотвердой спине, он решил написать роман Жозе Сарамаго. Вот что у него получилось.

А если шутки в сторону, то это роман-притча, обманчиво простой и феерически прекрасный, как оптическая иллюзия, где в одном рисунке проступает множество других: от классической антиутопии (не путать с дистопией в этом случае) до царства божия и того идеального будущего, в реальности которого нас пытались уверить бо́льшую часть хаха-века. Но это среди прочего. Доевангельская мифология и пифагорейские забавы там тоже есть. И развитая не по годам детка. И… и… в общем. Читайте, когда выйдет «пароски», будет вам много радости и мудрости. -

"There is no place for cleverness here, only for the thing itself." Rest assured this random quote speaks inordinately to this book as thing itself shy of clever overreach, a gradual release of fey plot maneuvering to allegorical clump, a nod, a wart, gone. David's downline Jesus, [no Jesus in these pages] Jesus' apostle Simon, an unknown birth mother, miracles of imaginative almost. It's a refugee story that's half told and left wet. Childs play make believe. That.

-

Two stars only because of the suspicion that I must have missed something grave in the text - because it's Coetzee for God's sake. Very shockingly bad! If he'd written if before the Nobel, the committee would've had second thoughts.

Read Disgrace and Life and times of Michael K - avoid this. -

The book seem to part of a really long series (of which only two parts are published so far) that will allegorise life of Jesus and which Coetzee is still working on - and that might perhaps explain why it seems to unsatisfying as a story - or rather as a part of a story. Coetzee's books are often as strong as ideas discussed in them but, in this case, the ideas didn't hit me with the force I have gotten used to be expecting.

-

You throw your hands in exasperation, and I can see why.

I re-read this book, together with “Schooldays of Jesus” and “Death of Jesus” back to back in a single day following publication of the third (and final) volume in the trilogy.

My reviews of the second two, terribly disappointing, volumes in the trilogy are here:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

To save you reading with them my summary is "I suggest two possible choices: stick to the first volume or simply avoid the trilogy altogether"

----------------------------------------------------------------------

This book starts with Simón (a Middle Aged Man) and David (a 5-6 year old boy) arriving on a boat in a new country (having fled their homeland for reasons not made clear). We quickly learn that Simón is not David’s father but “adopted” him on the boat after an incident when a letter David was carrying, explaining who he is and who is mother is, is lost – Simón resolves to help David and to find his mother.

The book starts deeply in Kafkaesque territory – the new state they enter (and where they are given their names) is a drab and austere socialist state, where many of the inhabitants are immigrants, where food is largely restricted to bread and bean paste, the workers attend philosophical classes and other educational classes in the evenings and where much is free or cheap but basic and bureaucratically administered.

The society in which he settles is one that encourages both a forgetfulness about past (a washing clean of past lives) and a suppression of natural (or to that society illogical and unhelpful) passions and urges.

Simón takes a job as a stevedore – arguing with the other stevedores about what he senses is missing in their lives (passion as opposed to goodwill, meat as opposed to bread). He strikes up a friendship with a mother of one of David’s friends, Elena– who allows him to have sex with her but more to resolve his urges than from any passion or interest.

Simón is on a quest to find David’s mother – and while walking past a tennis court where he sees a woman Ynes and her two brother’s playing, he decides that she is David’s mother and rather oddly she accepts the role, moves out of her privileged housing and lives with David in Simón’s flat.

It is obvious from early on that David sees himself as special – and those around him (particularly Inés) encourage this thinking, with Simón perhaps the only dissenting voice.We like to believe we are special, my boy, each of us. But, strictly speaking, that cannot be so. If we were all special, there would be no specialness left. Yet we continue to believe in ourselves.

Simón buys David a children’s Don Quixote to teach him to read – and there are clear parallels between David and the Don Quixote character and his attitude to life and between that novel and something of what Coetzee is attempting here.Don Quixote is an unusual book. To the lady in the library who lent it to us it looks like a simple book for children, but in truth it isn’t simple at all. It presents the world to us through two pairs of eyes, Don Quixote’s eyes and Sancho’s eyes.

When David eventually starts school, he refuses to conform – arguing that numbers have their own identity and are much more than labels for sets of similar things, and so refusing to count or do addition conventionally – he also refuses to show any reading skills (despite it being clear that he taught himself to read from Don Quixote in only a few weeks).[He has] a specific deficit linked to symbolic activities. To working with words and numbers. He cannot read. He cannot write. He cannot count ……. He can recite all kinds of numbers, yes, but not in the right order. As for the marks he makes with his pencil, you may call them writing, he may call them writing, but they are not writing as generally understood. Whether they have a more private meaning I cannot say …… A specialist may be able to tell us whether there is some common factor underlying the deficit on the one hand and the inattentiveness on the other.

David’s unusual approach to numbers is discussed as:He won’t take the steps we take when we count: one step two step three. It is as if the numbers were islands floating in a great black see of nothingness, and he were each time being asked to close his eyes and launch himself across the void.

To which Simón is advised:As for being afraid of the empty space between numbers, have you ever pointed out to David that the number of numbers is infinite ….

There are good infinities and bad infinites, Simón … A bad infinity is like finding yourself in a dream, within another dream within yet another dream and so forth endlessly. Or finding yourself in a life that is only a prelude to another life, which is only a prelude et cetera. But the numbers aren’t like that. The numbers constitute a good infinity. Why? Because being infinite in number, they fill all the spaces in the universe packed against each other as tight as bricks.

The contrast between Simón’s philosophy (which would be more like our own) and that of the country he joins is interesting. The country rejects progress and history as meaningless, abstract concepts; sexual attraction is seen as illogical - a woman points out the lack of connection between physical attraction and the mechanics of sex and asks why if he loves her he wishes to push his most unattractive parts inside her.Is he insisting on the primacy of the personal (desire, love) over the universal (goodwill, benevolence). And why is he continually asking himself questions instead of just living like everyone else? Is it all part of a far too tardy transition from the old and comfortable (the personal) to the new and unsettling (the universal)?

But despite that Simón starts to conform very slowly to the society expectations – in particular his past life, before meeting David, barely features in his thoughts.

David’s unusual behaviour and in particular his unwillingness to conform to educational norms is seen as a symptom of his yearning for his true identity.The real I want to suggest is what David misses in his life. The experience of lacking the real includes the experience of lacking real parents. David has no anchor in life. Hence his withdrawal and retreat into a fantasy world where he feels more in control.

I would say that what is special about David is that he feels himself to be special, even abnormal …. David wants to know who he really is but when he asks he receives evasive answers like “What do you mean by real” and “We have no history, any of us, it is all washed out”. Can you blame him if he feels frustrated and rebellious, and then retreats into a private world where he is free to make up his own answers.

When the authorities decide to move David to an institution, Ynes and Simón (and a hitchhiker they pick up) flee for the countryside.

The book (like the trilogy) is written in Coetzee’s trademark austere and sparse writing – with stilted and formal dialogue and with a lack of adjectives or description, and actually read as though translated (for example from German or Russian).

After a strong start thought I felt that by the book’s end the limited plot was increasingly seeming to act simply as a filler for rather banal philosophical discussions and to the use of analogy for analogies sake.

And my end reaction was close to my opening quote.

Nevertheless this is the strongest in the series by some way – as a one off book it would have made I think a slightly failed but interesting experiment. -

diyalog yazmak zor, diyaloglar üstüne kurulu bir roman yazmak çok zor, diyaloglar üstüne kurulu bir romanla özgün bir dünya yaratıp çetrefil meseleleri işlemek çok çok zor. coetzee bunu başarıp bir de başardığını çocuk oyuncağıymış gibi gösteriyor diğer iyi romanlarında olduğu gibi.

romanın dünyası ilginç. yeni denen bir dünya, eskiyi unutmak, temizlenmek-arınmak üzerine kurulmuş. evrensel sorunların çoğunun çözüldüğü görülüyor. insanlar hırslarından, arzularından, tatminsizlik duygusundan kurtulmuş. tüketim çılgınlığı sona ermiş. düzenli, sakin, herkesin iyi niyetli olduğu bir hayat var. ancak bir yanıyla da tuhaf bir dünya bu. arzular olmayınca tutku yok, heyecan yok, hayal yok, aşk yok. bireye dair her şey evrensele feda edilmiş. büyük fedakarlık, ağır bir kabullenme. ve bu dünyada kabullenmeyen, sıra dışı bir çocuk.

arzuların, tutkuların insanı mutsuzluğa, toplumları felakete sürüklediği genel kabülüne farklı ve özgün bir bakış getiriyor isa'nın çocukluğu. bir anlamda, romansal bir düşünce deneyi. bağ kurulması kolay olmayabilir ama eksiklik değil bu. aksine romanın özü bağsızlık-bağlantısızlık. biçimde ve içerikte hissedilmesi, hissedilmesi gerektiği için. -

Será uma falta de respeito dizer que um livro, escrito por um Nobel da literatura, é uma grande porcaria? Mas é o que me ocorre pensar de um livro que fala tanto de cócó; desde desentupimento de sanitas, a conselhos para não comer carne de porco, porque os referidos animais comem cócó e, por isso, "A carne de porco é carne de cócó."...

Piadinhas de mau gosto à parte, confesso que não achei qualquer interesse nesta obra, sendo o mais provável que eu não tenha entendido a mensagem que lhe está subjacente. Eu nem sequer o título consigo perceber...

A acção passa-se num lugar ao qual chegam refugiados, que são alojados e apoiados pelos que já lá estão. David é um menino de cinco anos que - não se sabe como - foi separado dos pais e acolhido por Simon, um homem que procura encontrar-lhe uma mãe.

A primeira parte do livro é interessante mas, a partir da segunda metade, com os diálogos com que Simon tenta transmitir a sua filosofia de certo e errado a David, perdi a paciência e terminei a leitura na diagonal. -

Daha önce sırasıyla 'Utanç', 'Barbarları Beklerken' ve 'Yavaş Adam'ı okumuştum Coetzee'den. Barbarları Beklerken; tüyleri diken diken eden, etkisinden uzun süre kurtulamadığım bir 'başyapıt'tı. Utanç ve Yavaş Adam da heyecanla okuduğum ve Coetzee'nin ustalıkla yarattığı tekinsiz felsefi atmosferin izlerini taşıyan eserlerdi.

İsa'nın Çocukluğu ise bir üçlemenin ilk kitabı, yeni basıldı, diğer iki kitap ise henüz yayımlanmadı. Annesini ve babasını kaybetmiş 5 yaşlarında bir çocuk (David) ile David'in annesini bulmayı kendine görev edinen 45 yaşlarındaki bir adamın (Simon) hikâyesi. Simon yeni bir ülkeye göç etmek için bindikleri gemide David'i kanatları altına alır. Aslında, David ve Simon adları dahi onlara adım attıkları yeni ülkede kayıt esnasında verilmiştir; yaşları tahminidir; geçmişleri siliktir. Yersiz yurtsuzluğa, geçmişsizliğe, 'anılara sahip olmanın anısı'na dair bir romandır İsa'nın Çocukluğu.

"Doğru, hiç anım yok. Ama yine de imgeler var, imgelerin gölgeleri var. Nasıl olduğunu açıklayamıyorum. Daha derinde bir şeyler direniyor, anılara sahip olmanın anısı diyorum ben buna..."

"Don Quijote olağandışı bir kitaptır. Dünyayı farklı iki çift gözden sunar bize: Don Quijote'un gözünden ve Sancho'nun gözünden. Don Quijote'ya göre savaştığı şeyler devdir. Sancho'ya göre bunlar yeldeğirmenidir. Büyük çoğunluğumuz bunların yeldeğirmeni olduğu konusunda Sancho'ya hak veririz..."

David'in okumayı (okula gitmeden önce) Simon'la birlikte kütüphaneden ödünç aldıkları Don Quijote kitabından öğrendiği ortaya çıkar. Çocuk denen şey, Coetzee'ye göre, Don Quijote'u anlayabilme melekelerini yitirmemiştir, Sancho'ya hak vermeyi bilmez. Modern romanın kurucusu Cervantes'e gönderilen bu selam ne anlama gelmektedir? Geçmişsizliği konu edinen bir romancının, yani Coetzee'nin; ilk modern roman olan Don Quijote'a atfı neyle izah edilebilir?

Don Quijote 500 yıl önce evinden çıktı ve dünya paramparça oldu. Romancılar, roman sanatı ile, modern dünyanın bulanık resmine dair çok şey söylediler. Coetzee de bitmeyen bir seyahat ve göç hikâyesi ile kapıların ardındaki kapıları gösteriyor. Roman bitiyor ama çağrışımları tükenmiyor. -

إني لشديد التأثر بكاتب جاد جدا، أما الكاتب الفكاهي يمكن له أن يصبح مهرجا أو فيلسوفا ! مِنَ المعروف أن كويتزي يحب العُزلة والابتعاد عن الناس، ويَتجنَّب الدعاية لنفسه وأعماله، وهو يَتمتَّع بالانضباط الذاتي كالرُّهبان، والتفاني في العمل. إنه لا يُدخِّن، ولا يأكل اللحوم، ويسير مسافات طويلة للحفاظ على لياقته.

عندما أعلن عن حصوله جائزة نوبل للآداب عام 2003 سارعتْ وسائل الإعلام إلى بيته دون أن يجدوا له أي أثر هناك سوى جاره الملاصق لبيته: لا أعرف عنه شيئا، لكن ما أعرفه هو أنني لم أر فيه يوما يبتسم أبدا.

ربما يكون ذلك أمرا غير جيد، لأنك لا تريد أن تصدم بعبء هذا الرجل الجاد في الحياة اليومية لا سيما أنك لا تحب التعرف إلى شخص بهذه السمة المنفرة، إلا أن كونه كاتبا يخفف من حدة ذلك، لأن ما يصدر عنه من نص إبداعي يخرج من رحم تلك الجدية، مما يجعل منه كاتبا عظيما، كاتبا ذا طابع خاص.

أوووه نسيت أن أكتب شيئا عن الرواية، بصراحة تناسيت، ربما لأنني لا أريد تحمل المسؤولية أمام القراء، وأمام كويتزي المأخوذ بالكتابة الصارمة، والموضوعات الصارمة إلخ، المهم لا تقرؤوا "طفولة جيسوس" ! -

Extraño libro del escritor Sudafricano.

La historia se desarrolla en una sociedad configurada de manera distinta a la nuestra. Somos nosotros y no somos. Es una distopía??

Hay muchos cuestionamientos al orden y un perpetuo sentido de búsqueda. Hace pensar al lector.

Coetzee juega con nosotros, nos hace desear que se produzca un milagro o algo relacionado con el Jesús del título. Queremos encontrar referencias bíblicas en todo momento, pero, las hay?

Googleando, me encuentro que en 2016 se editó la continuación de este libro ("The schooldays of Jesus") Sin traducción al español aún. -

Αυτό το βιβλίο υπήρχε καιρό στο ράφι μου χωρίς να το πιάνω στα χέρια μου, τώρα καταλαβαίνω το λόγο. Βαρετό. Τουλάχιστον διαβάζεται γρήγορα.