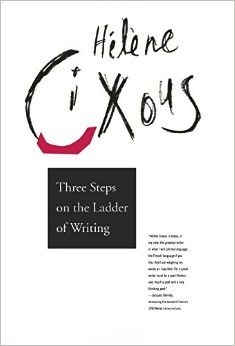

| Title | : | Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0231076592 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780231076593 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 162 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1993 |

Cixous's love of language and passion for the written word is evident on every page. Her emotive style draws heavily on the writers she most admires: the Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector, the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, the Austrian novelists Ingeborg Bachmann and Thomas Bernhard, Dostoyevsky, and, most of all, Kafka.

Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing Reviews

-

We must have death, but young, present, ferocious, fresh death, the death of the day, today's death. The one that comes right up to us so suddenly we don't have time to avoid it, I mean to avoid feeling its breath touching us. Ha!

H

H ~

. H

This book is my scripture. I don't even know what that means, but the word feels right in this case. I want to absorb it entirely. It was emotionally devastating even though there were no moving scenes--there is no narrative; no, this is an Instruction Manual!! Ha, what a joke, because that is the least of it

H

H .

H

HThe desire to die is the desire to know; it is not the desire to disappear, and it is not suicide; it is the desire to enjoy.

For starters it should be required reading in every writing school. Definitely in every art school. Yes, even in any sort of educational institution. I cannot see how it can be any other way. And yet it is. Curious

H

~ H

H

H

H

.

H

HYou will tell me everyone dies, but not everyone dies of writing.

H

HWhy do we desire to die so much? Because we desire to say so much.

Though fair warning: for a beginning writer, there is no real practical advice in this book. Well, maybe one, and I can remember exactly what it was, but it's like a paragraph. For the rest of the book, what the reader will come away with is not a new set of skills on writing, but a new perspective on writing, a deeper understanding of reading (and the importance, difficulty, and seriousness of really reading), and lastly, a feel for the impulse to write, and what that impulse necessarily entails

H

.

H

H

H

. H

H

H

H .*In the direction of truth*, because telling the truth and dying go together. Something allies truth with death. We cannot bear to tell the truth, except in the final hour, at the last minute, since to do so earlier costs too much. But when does the last minute come?

Perhaps going in the direction of what we call truth is, at least, to "unlie," not to lie. Our lives are buildings made up of lies. We have to lie to live. But to write we must try to unlie. Something renders going in the direction of truth and dying almost synonymous. It is dangerous to go in the direction of truth. We cannot read about it, we cannot bear it, we cannot say it; all we can think is that only at the very last minute will you know what you are going to say, though we never know when the last minute will be.

In writing school, during workshops, I was always tempted to give the criticism "what's at stake here?"--i.e. "where is the urgency in this?" But I rarely voiced this concern, because it was seen by the other participants and the teacher as not a very helpful one.

H

.

H

H ~

H

H

What does this criticism even mean? And how is it helpful, since one cannot learn urgency? Better to stick to the craft! Because that word 'urgency' gets too personal--as if criticizing the writer--from what depths are you writing out of?--rather than the work.

And perhaps they're right. You can't teach it. But Cixous doesn't try to teach urgency. She makes a case for the urgency of urgency

H

H

H

. H

H

H

.

H .

Hwe must lie, mostly as a result of two needs: our need for love and cowardice. The cowardice of love but also love's courage. Cowardice and courage are so close that they are often exchanged. Cowardice is probably the strange, tortuous path of courage. Love is tortuous. So it is only at the very last page of a book that we perhaps get a chance to say what we have never said, write what we have never written all our lives, i.e., the most precarious, the best, in other words, the worst.

Cixous is a poetic writer, but not in the popular understanding of that term "poetic". She writes simply and directly exactly what is there. For true poetry is not circuitous, slant or not--it is the shortest route from A to B, i.e. it is, unintuitively, a straight line

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

HTry to look for the worst in yourself and confide it where there is no process of erasure, where the worst remains the worst. Try to write the worst and you will see that the worst will turn against you and, treacherously, will try to veil the worst. For we cannot bear the worst. Writing the worst is an exercise that requires us to be stronger than ourselves. My authors have killed.

I found myself reading sentences over and over again, to understand better but also--mostly--to delay the pain of the direct encounter, to allow time for the truth to land and settle in. To become more prosaic and therefore digestible. That is how you recognize truth's appearance, when it is sudden and indigestible

H

.

.

H

H

H

H

H

H

HMan cannot bear having committed what I would call *a perfect crime*, since no one knows about it. Even the dog does not know about it. The crime is so perfect it is imperfect. The really perfect crime should indeed be imperfect. But this crime, perpetrated on a dog, is not recognized as a crime, and this is what Man must deal with. We are criminals and we do not know how to express or prove that we are criminals. The problem is that if, as criminals, we were recognized as such, we would have to pay for the crime. Yet if we paid, the crime would disappear and our debt would be wiped out. We must keep our crime in order to keep our crime safe, to avoid the terrible fate of being forgiven.

H

H

H

*The inclination for avowal*, the desire for avowal, the yearning to taste the taste of avowal, is what compels us to write: both the need to avow and its impossibility. Because most of the time the moment we avow we fall into the snare of atonement: confession--and forgetfulness. Confession is the worst thing: it disavows what it avows.

She requires the same of writers: that they too look unflinchingly into the face of the worst, most uncomfortable, most otherworldly

H

H

H .

H

. H

H

.

H

H

H

H .We could think over these mysteries but we don't. We are unable to inscribe or write them since we don't know who we are, something we never consider since we always take ourselves for ourselves; and from this point on we no longer know anything.

Within the book lurks the temptation to misread the book. For what it proposes is at once obvious, teetering at the edge of cliche, yet not obvious at all. It is easy, then, to read into it the tired argument of the suffering artist, that all good art comes out of suffering and pain.

H

H

H

There is some truth to the cliche, but the very form of the cliche demeans it through vulgarity and simplicity. And with it the reader dismisses the entire package as untrue. But what Cixous proposes here, when not misread, is nothing so crude. It is full of subtlety and does not involve suffering, death, borders, metamorphosis, displacement or sexuality in any of the traditional ways. It's theory that's not theoretical but felt. She breaks these ideas down in a compost heap of lived and read experiences, through her favorite writers: Ingeborg Bachmann, Clarice Lispector, Thomas Bernhard, Marina Tsvetaeva, Kafka, Edgar Allan Poe, and Jean Genet. These are who she calls descenders on the ladder of writing:To us this ladder has a descending movement, because the ascent, which evokes effort and diffuculty, is toward the bottom. I say ascent downward because we ordinarily believe the descent is easy. The writers I love are descenders, explorers of the lowest and deepest.

And Cixous is a great reader. I enjoy reading her version of Poe more than reading Poe himself, directly. I want to re-read Clarice Lispector with Cixous's eyes, since I have always admired Lispector, but have never completely connected with her emotionally, and the fault is probably mine. As for some of the other writers like Ingeborg Bachmann and Thomas Bernhard, I beam with joy and recognition when she talks about them, as I also read them in a very similar way

H

.

H

H

H .

HIf the truth about loving or hateful choices were revealed it would break open the earth's crust. Which is why we live in legalized and general delusion. Fiction takes the place of reality. This is why simply naming one of these turns of the unconscious that are part of our strange human adventure engenders such upsets (which are at once intimate, individual, and political); why consciously or unconsciously we constantly try to save ourselves from this naming.

Cixous understands so much that is pre-speech, pre-understanding, so much that is under the surface and she treats her subject with such care not to explain it away, but to bring just the smallest glint of light onto it. I fear that this book will mean nothing to those who don't have this book inside of them already. That was my experience. I feel like I've always known the book even before I read the book. And that reading the words just brought them forth in my mind more clearly than ever

.

.

H

H

.

.

H

.One has to go away, leave the self. How far must one not arrive in order to write, how far must one wander and wear out and have pleasure? One must walk as far as the night. One's own night. Walking through the self toward dark.

-

Reading is not as insignificant as we claim. First we must steal the key to the library. Reading is a provocation, a rebellion: we open the book’s door, pretending it is a simple paperback cover, and in broad daylight escape!

Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing is a magnificent exposition on the duality of reading and writing. It is based on lectures that Cixous delivered at Cal Irvine and it is certainly worth everyone's time. The Ladder in question is based on the letter H, a bridge as well as a ladder, it connects and most important for Cixous this Jacob's Ladder allows for the descent, an earthy departure for the furtive and organic. Not exactly the Carnival but undoubtedly in a similar post code. Cixous aligns her favorite authors for her cause: Lispector, Genet, Mandalstam, Bachman etc. The result is playful yet transcendent. -

این کتاب مهمترین کتابیست که از سیکسو_ رفیقِ ژک دریدا و همشهری الجزایریاش_ ترجمه شده. سیکسو در اینجا به قاعدههای روشمند نوشتار نمیپردازد.بلکه بیشتر فرآیندهای ناخودآگاه نوشتار را موردِ مداقه قرار میدهد که عبارتند از: مردگان، رویاها و ریشهها

در هریک از این موضوعات کار نویسندگان مورد علاقهاش یعنی ژنه، کلاریسی لیسپکتور، کافکا، توماس برنهارد و مارینا تسوهتایوا را بررسی میکند. سبک متافیزیکوار نوشتار او را پیشتر در کتاب بصر و باغواقعی خوانده بودم_ این سبک بیشتر وابسته به جنون خواندن و درک زیبایی حاصل از نوشتن است. فیالواقع این کتاب هم دربردارندهی تکنیک نیست، بلکه کتابیست برای علقهی افرادی همرأی با سیکسو و احتمالا اگر از آن نویسندگان مذکور چیزکی خوانده باشد به کامتان خوش مینشیند

.

پ.ن:ترجمه به ویراستاری بسیار نیاز دارد و زیاده از حد سنگین و ثقیل است -

You've got to hand it to the French. They sure do know how to belt out stunning books of philosophically enriched non-fiction. This is another. A beautifully written work of art.

-

This book is beautiful--I truly recommend it to anyone who feels great emotions when either reading or writing. Cixous explores a beautiful aspect of what it means to write, to give self to language, to figuratively die for it. And she writes with powerful passion; it is as though you linger in the vibrations of the words on each page (or at least on your favourite pages), and when you finish reading this book it leaves you in a bit of a soulful trance.

-

The book that inspired me to study literature...One of the best books I've ever read...a book that lived in me before I read it...a coming home.

-

چقدر سیکسو لطیف مینویسه. چقدر این کتاب اشتیاق به خوندن و نوشتن رو زنده میکنه.

-

Though this book is titled 3 Steps on the Ladder of Writing, it is not a type of writing book that is practical. This was more about theory and literary criticism and what I would imagine a really cool professor would teach their more advanced writing students in some elite university. I’ve been reading this book slowly for 2 months. She mainly focused on writers like Clarice Lispector (who I adore) and Kafka (whom I’ve only read Metamorphosis by but am eager to get to more of his work) and Bachmann and Bernhard who I recently randomly purchased, and Tsvetaeva who I read years ago and am now rereading. And Edgar Allen Poe who I have not read but now I want to. So I guess you could say this felt like a perfect match. Honestly, while I love Clarice there are some books of hers I struggle with like The Passion according to G.H. and Hèlénes dissection of if it helped me read Clarice differently. And that’s the thing about this book, it’s a book on how to be a better reader. She highlights these writers because she says for her there is no other way to write. For her, there’s no other point in writing. This book is split up into the dead, dreams, and roots. She says these writers are the extremists of writers, meaning they run to death, that thing we all hide from. They confront it daily in their work. Mortality is not just a theme in their work but perhaps a way of life— being so desperately aware of it. She is not naive, she knows to be this type of writer you must sacrifice everything. Because everything suffers. She talks about translation and how much that changes how we read and interpret. What is left out? She talks about truth in a text, good and evil, and unclean meat in the Bible. I am writing this week's substack on this book because I realize I am doing it a disservice here in the allotted text space and a masterpiece such as this deserves more space on the page. So for now just know that what Hèléne thinks of those writers is what I think of her. I too want to write towards death but I too want to read like Hèléne does. Critically, with heart, and mind, pushing the boundaries on what can be understood and defining art in literature.

-

Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing is a contemplation by Hélène Cixous regarding essential elements of writing that distinguish pieces of vision and profundity from the slew of writing available on the market. Cixous channels her focus on authors such as Franz Kafka and Clarice Lespaector whom have impacted the history of literature and have given the world gifts of writing that permeate the human experience and communicate fundamental aspects of mundane life with an artistic gesture. The book is categorized into three main sections: “The School of the Dead,” “The School of Dreams,” and “The School of Roots.” Each section sings to the reader in poetic diction and romanticized concepts, conveying an extreme respect and admiration for language and those whom share and delight in its revere.

Contained in the brief introduction, Cixous delineates some of her beliefs regarding writing and its power to unify two unrelated fields. Using the letter H to visually represent a ladder, Cixous weaves an extended metaphor that respectively represents language’s jurisdiction to create “a passageway between two shores” (Cixous 3). Furthermore, it is brought to awareness that in the French alphabet, H is omni-gendered, switching between feminine, neutral and masculine at will, which creates a space of mutability that encompasses all possibilities and cultivates increasing opportunities for relation. Despite writing’s ability to cohesively script a whole from two distant halves, all writing shares a common root. Cixous states that “the texts that call me have different voices. But they all have one voice in common, they all have, with their differences, a certain music I am attuned to” (Cixous 5). The aforementioned declaration exemplifies Cixous’s adoration of language and how her basic qualifier of a moving piece of literature is that it sings to her from a level of depth and profundity within her psyche; an quality of downward ascension pervades the authors whom climb her ladder of writing, providing an expression of reaching that touches the innermost depth of her soul.

In “The School of the Dead,” living and writing are expressed as the same action, compelling the reader to question his or her relationship to life, death, the activities in life that support vitality and the habits that kill individuals with monotony and petrification. The function of writing is to address the immediate mortality faced by all humanity, to come to peace with this fact and to see, with eyes wide open, that life is ephemeral and cannot (in a physical sense) be preserved. Cixous states that “Writing is learning to die. It’s learning not to be afraid, in other words to live at the extremity of life, which is what the dead, death give us” (Cixous 10). In the dualistic reality of life, life invades death and vice versa, creating an inextricable bond between both, like the rung contained within the letter H that connects two polar compliments. In a letter to a friend Pollak, Kafka wrote: “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside of us” (Kafka 16). Kafka’s belief about writing proposes the idea that writing must wake up the dead components of the reader’s psyche with a violent force. Cixous proudly declares that “When I write I escape myself, I uproot myself,” a demonstration of writing’s sheer power to shake an individual from themselves or at least, his or her definition of self (Cixous 21). Lispector additionally provides commentary on writing and Cixous interprets her conveyance of writing as “the hour of relinquishing all the lies that have helped us live” (Cixous 37). Writing is akin to the connection between individuals and their breath, providing an honest, forceful awareness of living and a relinquishment of fear surrounding the experience of death.

The continuation of “The School of the Dead” leads to “The School of Dreams,” where individuals look past their avoidances and disavowal to peer, without obstructions, into the contents of their psyches. Dreaming teaches individuals to forget about a storyline or contextual setting while living through experiences, furthermore teaching them to live independently of expectation and open themselves to the yearning drive of the soul. Writing is a process of creation and proliferation is the inherent goal of human’s genetic programming; this similarity unites writing with the desires of the soul, therefore writing becomes an act that nourishes deep human needs. Dreams express the workings of the subconscious without transition or translation; interpretation murders the magic found within dreams, an attempt to predict the unpredictability of human nature.

Reality cannot be calculated and is dangerous, providing humanity and all nature with a messy experience, one that is not divided into right and wrong, safe and hazardous; an experience that is impure. As “The School of Roots” contains in its teaching, “to be ‘imund,’ to be unclean with joy…[is] the moment you cross the line the law has drawn by wording, verb(aliz)ing, you are supposed to be out of the world. You no longer belong to the world” (Cixous 117). Those whom find themselves peering in at the world from the outside have climbed Cixous ladder of writing, reaching further than social constrains and crawling into a world in which they no longer perceive themselves as engaging in writing, but they see themselves and their psyches as being written into fruition. To understand writing is to understand that books exist without a singular creator, they exist as an extension of life, they breathe with each breath of a reader and they persevere through time by reaching toward the next reader to touch the innermost part of his or her psyche. -

"We then spend our lives not seeing what we saw" (8)

"That is the definition of truth, it is the thing you must not say" (38).

"Thinking is trying to think the unthinkable..." (38) -

I am astonished, always mesmerized, by Cixous' lucid and extremely poetic usage of language and at the intensity of the love that transpires for her subjects. Extremely inspiring, a book to cherish and return to numerous times.

-

نقاشی تلاشیست برای نقاشی کردن چیزی که نمیتوانی نقاشیاش کنی و نوشتن هم نوشتن چیزیست که قبل از نوشتنش نمیدانی چیست، تلاشی کورکورانه، با کلمات. در محل تلاقی کوری و نور اتفاق میافتد. کافکا میگوید -سطر کوچکی گم لابلای نوشتههایش- «به سوی اعماق، به سوی اعماق.» رفتن به اعماق دقیقاً همان کاریست که این آدمها میکنند - دقیقاً کاری که داستایفسکی دو قرن گذشته انجام میداد.

نویسنده در مورد چنین نوشتنی حرف میزند. در مورد ساز و کارش. اینکه چطور به مرگ و رویا گره خورده. با ارجاع فراوان به نویسندههای مورد علاقهاش. به کلاریس لیسپکتور، توماس برنهارد، کافکا و چندتای دیگر. همانهایی که ظاهراً شروع میکنند داستانی تعریف کنند اما هرچه جلوتر میروند کمتر از داستانی که قرار بوده بگویند تعریف میکنند و انگار در چیز دیگری گیر میافتند، نوعی تله، و آن چیز دیگر را با انگشت زخم میکنند. با همین نگاه است که میگوید:

ممکن است که مؤلف سر نوشتن خودش را بکشد. تنها کتابی که ارزش نوشته شدن دارد همانیست که جرأت و قدرت نوشتنش را نداریم. کتابی که آزارمان میدهد (مایی که مینویسیمش)، کتابی که لرزه به جانمان میاندازد، ملتهب میکند، به خونریزی میاندازد. جنگیست علیه خودمان، علیه مؤلف، یکی از ما بایستی تلف شود، بمیرد.

با این نگاه نسبتاً گنگ و جادویی به فرایند نوشتن، تعجبی نیست که خواب و رویا هم برایش مهمند، الهامبخشند، و البته اینقدر خالصانه به ماجرا نگاه می کند که حتی ترجیح میدهد رویاها به تفسیر «آلوده» نشوند:

با ذوق و شوق «تفسیر رویاها» را میخواندم، اما، علیرغم اینکه کتاب فوقالعادهایست، حقیقتاً قاتل رویاهاست چرا که آنها را «تفسیر» میکند. زور میزند تا رویا چیزی که در گلویش گیر کرده را سرفه کند و بالا بیاورد. رویاهایی که فروید در «تفسیر رویاها» تفسیر کرده همگی شبیه همند: البته که محتوایشان با هم فرقی میکند، هستههایی متفاوت، اما یکسان نوشته شدهاند. رویاها توسط فروید نوشته شدهاند�� هم رویاهای خودش و هم مال دیگران. گوشت رویا دیگر از دست رفته. این خطر بزرگیست. بایستی یاد بگیریم که با رویا مثل رویا برخورد کنیم، دست و پایش را نبندیم، بیاعتنا به شیاطین داخلی و خارجی که رویاها را نابود میکنند.

حدسم این است کسی که از چنین نوشتنی خوشش بیاید، از خواندن این انشای بلند هم کیف کند.اما کسی که دنبال قصه و انسجام روایت و مولفههای داستانِ صحیح و ضرباهنگِ سریع و کسل نشدن مخاطب باشد احتمالا خیلی سریع همان صفحات اول از این انشای طولانی هم کسل میشود.

-

Here are some quotes from this provocative book that elliptically engages Lispector, Bachmann, Bernhard, Kafka, and others:

"Writing is learning to die. It's learning not to be afraid, in other words to live at the extremity of life, which is what the dead, death, give us."

"The writers I feel close to are those who play with fire, those who play seriously with their own mortality, go further, go too far, sometimes go as far as catching fire, as far as being seized with fire."

"Writing and reading are not separate, reading is a part of writing. A real reader is a writer. A real reader is already on the way to writing."

"Reading is a provocation, a rebellion..."

"It can also happen that an author will kill himself or herself writing. The only book that is worth writing is the one we don't have the courage or strength to write. The book that hurts us (we who are writing), that makes us tremble, redden, bleed. It is combat against ourselves, the author; one of us must be vanquished or die."

"I have always loved the writers who I call writers of extremity, those who take themselves to the extremes of experience, thought, life."

"The thing that is both known and unknown, the most unknown and the best unknown, this is what we are looking for when we write. We go toward the best known unknown thing, where knowing and not knowing touch, where we hope we will know what is unknown. Where we hope we will not be afraid of understanding the incomprehensible, facing the invisible, hearing the inaudible, thinking the unthinkable, which is of course: thinking. Thinking is trying to think the unthinkable: thinking the thinkable is not worth the effort. Painting is trying to paint what you cannot paint and writing is writing what you cannot know before you have written: it is preknowing and not knowing, blindly, with words."

“We must work. The earth of writing. To the point of becoming the earth. Humble work. Without reward. Except joy.” -

How do you review a book you have read and continue to read. Each page is a revelation. The writing is a synonym for living, breathing and being. I hate the book for having brought me to a place where I will never be that same smug person I have been getting by with all of my life.

I would like to see someone write a book about this book. And then I would like to see the book that is inspired by that book. The spiral is opening.

The date I noted on this form is the most recent time I have reread the book -

You know I think writing appreciations of texts instead of interpreting is one of the worst ideas of the 20th century. Like I think this is well done and I like a lot of the same books as her; but it is just not my kind of criticism.

-

A philosophical exploration into what it means to write. Categorizing writing into three facets, the School of the Dead, School of Dreams, and School of Roots, Cixous captivates with her poetic language, and offers strange yet delightful explanations for what truth means in writing. Not quite criticism, not quite creative writing, ultimately Cixous is able to deliver a book that, as Kafka would say, hits you like a blow to the head - a unique piece that you ponder over for time to come.

-

This is a book about reading as much as writing -- Cixous is an attentive, nuanced, and most importantly, a loving and joyful reader. I love her poetic deployment of erudition, the way she uses her knowledge of language and languages to open up the texts she examines. "I have talked about school, not goals or diplomas, but places of learning and maturing," she writes, and also: "School is interminable."

-

This is the most powerful book I have ever read about writing and life. Cixous power is that she not only writes as a critic but as a poet. Her lines are tight and a times lyrical.

The are so many facets to this book that I read it over and over again and always find something new. -

This book made me want to write a Gothic novel, among other things. Too many wonderful quotes to write here, and insights about writing too deep to be read outside of the book as a whole. If you are looking for someone to tell you how to write (not what to write), interlibrary loan this shit.

-

This is one of my favorite books--both as a reader and as a writer.

-

the last section about the flowers was so beautiful

-

How do I even give this stars? I have been reading this motherfucker for years. YEARS. And I refused to take it off my "currently reading" list out of some stubborn idea that I was actually currently reading it instead of just *wishing* I was currently reading it. Well, now I have READ IT.

I'm sorry to say I cannot really report back on these ideas. I'm super into Cixous's ideas, and I understand why reading her is the way it is. But still I find her very hard to read. -

“We must work. The earth of writing. To the point of becoming the earth. Humble work. Without reward. Except joy.

School is interminable.” -

• Writing as an H: the I of one language, the I of another, between the two a line that makes them vibrate. H as the stylized outline of a ladder.

o H, pronounced hache/axe in French, cuts.

o If a, B, C, D, E are masculine, H is masculine, neuter, or feminine at will.

o H is a letter out of breath. Aspirated. It protects le heros, la hardiesse, la harpe, Iharmonic, le hasard, la hauteur, I'heure from any excessive hurt.

• The ladder is neither immobile nor empty; it is animated. IT incorporates the movement it arouses and inscribes. “my ladder is frequented.”

• The School of the Dead

o When choosing a text I am called: I obey the call of certain texts or I am rejected by others.

o To us this ladder has a descending movement, because the ascent, which evokes effort and difficulty, is toward the bottom.

There are two ways of clambering downward—by plunging into the earth and going deep into the sea—and neither is easy. The element (sea and earth, language and thought) resists

Descend towards the truth

o The first moment of writing is the School of the Dead, and the second moment of writing is the School of Dreams. The third moment, the most advanced, the highest, the deepest, is the School of Roots.

• 1. We Need a Dead(wo)man to Begin

o To begin (writing, living) we must have death. I like the dead, they are the doorkeepers who while closing one side “give” way to the other.

o We must have death, but young, present, ferocious, fresh death, the death of the day, today’s death. The one that comes right up to us so suddenly we don’t have time to avoid

o Writing is this effort not to obliterate the picture, not to forget

o As future skinned animals, to go to school we must pass before a butcher’s shop, through the slaughter, to the cemetery door.

o to get to school everyday I passed (I went by bus, the K line) in front of the Catholic cemetery. The Catholic cemetery was my death as a Jewish girl. The cemetery spoke Latin.

o Writing is learning to die.

o I’ll say this in parenthesis: perhaps the dead man is the one who gives, while the dead woman gives less

o Perhaps we can’t receive from the dead mother what the dead father gives us? The dead man’s death gives us the essential primitive experience, access to the other world, which is not without warning or noise but which is without the loss of our birthplace.

o The first book I wrote rose from my father’s tomb.

o We don’t know, either universally or individually, exactly what our relationship to the dead is. Individually, it constitutes part of our work, our work of love, not of hate or destruction; we must think through each relationship. We can think this with the help of writing, if we know how to write, if we dare write

o Lydia Tchoukovskaia’s husband is deported. She is told his sentence is “ten years without the right to correspond.” So, like hundreds of women, she lined up with parcels in front of the prison walls—until the day she learned that “ten years without the right to correspond” was a metaphor for: immediate execution. For several years she had been carrying inside herself a living deadman, alive within her, decomposing outside her.

o This is the story of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Mr. Valdemar.’” Mr. Valdemar calls the narrator, who is a hypnotist, telling him to come quickly since he is about to die. It is time, according to their pact, for him to hypnotize the dying man. The narrator arrives. Mr. Valdemar doesn’t hear the narrator, who has just enough time to catch his breath and put him to sleep. After rather a long time, we feel that Mr. Valdemar, who is now in a hypnotic state, is suffering terribly. When the narrator “wakes up” Mr. Valdemar, the sleeper’s life breaks out in a flow of pus because he “was” dead. This is Tchoukovskaia’s story, the loved one remained inside her, a dead man inexplicably without his death.

o In If This Is a Man Primo Levi speaks of the dream he has, which is, he says, a dream all the deportees had, the absolute nightmare, the dream of the impossible return.

o I too believe we should only read those books that “wound” us and “stab” us, “wake us up with a blow on the head” or strike us like terrible events, that do and don’t do us good, that don’t do us good in doing us good, a book “like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves,” or that is “like being banished into forests far from everyone,” or books that are “like a suicide.” Or as he says at the end: a book “must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.”

But very few books are axes

• That the Act of Reading or Writing Be a Mortal Act; or, Reading/Writing, Escape in Broad Daylight

o Look for instance at Rembrandt’s picture entitled “The Jewish Fian¬cee.” It is softly strange.

• What is Reading? It’s Eating on the Sly

o And what books do we read as we become strangers in joy? Those that teach us how to die.

o The text flees paragraph by paragraph. “Montaigne” comes to an end in twenty-two steps or paragraphs—twenty-two bounds. Since you read with your body, your body paragraphs

o I know a type of painter who did exactly the same thing. He painted his poems with the blush of the women he loved. I am talking about Rilke. Rilke is always murdering someone with his poetry.

• The Author Is in the Dark; or, The Self-Portrait of a Blind Painter

o It can also happen that an author will kill himself or herself writing. The only book that is worth writing is the one we don’t have the courage or strength to write.

o Lispector’s The Hour of the Star is the final book, Clarice abandoned herself for

o I am not talking about suicide: the desire to die and the temptation of suicide i are two different things; suicide is murder, suicide is aimed at someone ( or something, whereas the desire to die is not this at all—^which is why > we can’t talk about it

o books are exactly those steps that should lead us to the point where oppositions meet, and, coinciding, suddenly open up to what Kafka would call “the Holy of the Holies.” But, as you know, to set foot in the Holy of the Holies, you must take everything off.

• The Inclination for Avowal

o (My authors have killed)

o We must bury. We must unbury the burying

o Meeting a dog you suddenly see the abyss of love. Such limitless love doesn’t fit our economy. We cannot cope with such an open, superhuman relation.

• Toward the Last Hour

• We Need the Scene of the Crime

o when we say to a woman that she is a man or to a man that he is a woman, it’s a terrible insult. This is why we cut one another’s throats

o Loving and killing absolutely cannot be disentangled. The only person who can kill us is clearly the person who loves us and whom we love.

o Writing is the delicate, difficult, and dangerous means of succeeding in avowing the unavowable. Are we capable of it? This is my desire. I too would like to die; though this doesn’t mean I have succeeded. I make the effort. So far I haven’t succeeded. In the meantime, I do the closest thing I can.

School of Dreams

• One of Kafka’s Dreams

o Anyone who has once been in a state of suspended animation can tell terrible stories about it, but he cannot say what it is like after death, he has been actually no nearer to death than anyone else

o For instance Moses certainly experienced something extraordinary on Mount Sinai, but instead of submitting to this extraordinary experience, like someone in a state of suspended ani¬mation, not answering and remaining quiet in his coffin, he fled down the mountain and, of course, had valuable things to tell, and loved, even more than before, the people to whom he had fled and then sacrificed his life for them, one might say: in gratitude.

o we may even wish death for ourselves, but not even in our thoughts should we wish to be alive and in the coffin without any chance of return, or to remain on Mount Sinai

o Here Kafka is telling us in a complex way about our inability to desire what we desire—the secret. Our difficulty and our inability.

• Who (What) Does Not Regard Us/ None of Our Business

o This is what Clarice Lispector tells us about in a text called “Love,” in which a woman. Ana, is accidentally surrendered to the face of God during an extraordinarily eloquent episode.® Ana is in a bus, she is carrying a shopping basket, she has all the distinguishing marks of the housewife, there are eggs in her basket, and in Ana’s head, which is like a basket full of eggs, are the eggs of her life; during the day, she contemplates her life over a low heat: she has everything she should, her husband, her children, furniture, etc. At this moment, without meaning to, she sees the face of God, in an instantaneous, unbearable, admirable vision: that is, she sees a blindman on the edge of the sidewalk, and this makes the eggs explode. She sees (here it’s even more complex) a blind man who is not only blind but who also chews. This is the secret of this powerful yet light scene: the blind man is chewing.

o The blind man: the one who doesn’t see us looking at him. We who are the looked-ats. We who live, eat, desire as we are looked upon. We who are looked-at lookers. But who never see ourselves as we are looked at, nor as we are seen. We who don’t know we are blind and chewing.

o Ana sees the face of God. You can die from it. You can also survive. Ana is wounded, split open. At the end of the text, she recloses what has been opened. But this might not have been reclosed.

• The School of Dreams is Located Under the Bed

o Jacob’s dream.

o The parental genealogy provides a background. Stemming from Abraham we are constantly in the space where Good and Evil are infinitely tangled. Violent events are strewn through the characters’ bio¬graphies. Then, as in a novel, we come to the small Isaac we left on the mountain, we progress through the story, and find a completely different Isaac.

o The story of Moses’ youth, for example, is astonishing. There is no one more ordinary than Moses; he is a man who experiences all manner of unexpected passions within himself, our Moses who, for centuries, has been the Moses of Michelangelo and not the Moses of the Bible. The Bible’s Moses cuts himself while shaving. He is afraid, he is a liar. He does many a thing under the table before being Up There with the other Tables. This is what the oneiric world of the Bible makes apparent to us. The light that bathes the Bible has the same crude and shameless color as the light that reigns over the unconscious. We are those who later on transform, displace, and canonize the Bible, paint and sculpt it another way.

o To begin with, Jacob leaves. We always find departure connected to decisive dreams: the bed is pushed aside. The nature of the dream in or from which we dream is important. We may have to leave our bed like a river overflowing its bed. Perhaps leaving the legitimate bed is a condi¬tion of the dream.

o I always felt glad, when I later grew up out of the Garden, that this dream came early in the Bible, that the Bible started dreaming quickly; I appropriated this dream. It remained my own version,

o The Bible continues in such a way that you never really know whether God is inside or outside the dream.

o In dreams we unvirgin ourselves.

• Dreams, Engendering, Creation

o A woman who writes is a woman who dreams about children. Our dream children are innumerable.

o The unconscious tells a tale of the supernatural possibility (it is always supernatural) of bringing a child to light, but the miracle in the dream is that you can have a child even when you cannot have a child. Even if you are too young or too old to have a child, even if you are eighty, you can still carry a child and give it birth and milk. And sometimes the milk is black.

o In the text, as in dreams, there is no entrance.

• How can we finishe a book, a dream?

o What happens at the end of a text?

• What Must we do to get to the school of dreams?

o The dreams interpreted by Freud in The Interpretation ofDreams are all alike: although there is a difference in content, a different nucleus, the writing is the same. The dreams are written by Freud, both his own and those of other people. The flesh of the dream is no longer there. This is the great danger. We must know how to treat the dream as a dream, to leave it free, and to distrust all the exterior and interior demons that destroy dreams.

School of Roots

• Birds, Women, and Writing

o I am interested in a chain of associations and signifiers composed of birds, women, and writing.

Leviticus laws on eating: the French distinction in French unclean is immonde^ which comes from the Latin immundus; it is the same word in Brazilian— immundo—and I’ll need this later.

Immundity as a category put forth by the He-Bible (3mp authors). Birds and women are outside it

Lispector on immundity

• I was knowing that the Bible’s impure animals are forbidden be¬ cause the imund is the root. For there are things created that have never made themselves beautiful, and have stayed just as they were when created, and only they continue to be the entirely complete root, they are not to be eaten. The fruit of good and evil, the eating of living matter, would expel me from the paradise of adornment and require me to walk forever through the desert with a shepherd’s staff. Many have been those who have walked in the desert with a staff.

to be “imund,” to be unclean with joy. Immondcy that is, out of the mundus (the viorld}. The monde, the world, that is so-called clean. The world that is on the good side of the law, that is “proper,” the world of order. The moment you cross the line the law has drawn by wording, verb(aliz)ing, you are supposed to be out of the world. You no longer belong to the world.

So why are those birds imund? Because. As you know, this is the secret of the law: “because.” This is the law’s logic. It is this terrible “because,” this senseless fatal “because” that has decided people’s fate, even in the extremity of the concentration camps. A FATAL BECAUSE

o The Sex of a Text

Lisable femininity, masculinity. -

I am writing a new work with three sections, the city, the corpses, the dreams;

A friend, as comments to a small part of the project shared with class, simply tells me about a book that has three sections: the school of the dead, the school of dreams, the school of roots. how strange is that?

stranger still is when reading that night an analysis of Anais Nin, Cixous is mentioned, for the second time on the same day in two seemingly unrelated context.

A few pages in the book and i already know why i need to read this...

Cixous is now one of the women i will come back to over and over again, i am sure of. -

Helen continues to foster my lust for ink, she adopts a philosophical approach coated in a beautiful garment of syntax, both talk to one another in a beautiful exposure.

The aura of the Deconstruction movement is vivaciously illuminating through the question of identity and feminism she perpetually correlated to the very simple act of writing.

A straight-out five