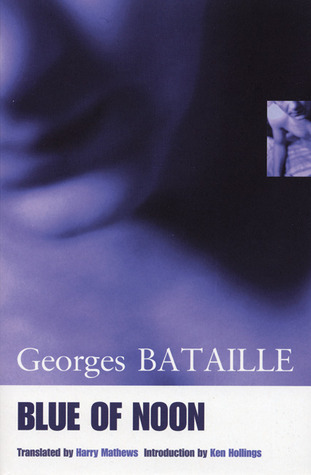

| Title | : | Blue of Noon |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0714530735 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780714530734 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 162 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1935 |

Blue of Noon Reviews

-

Unlike

Story of the Eye Blue of Noon doesn’t boast excess of sexual symbols but there is a profusion of existential signs instead. All that nausea and sickness and squalor of living so cherished by

Jean-Paul Sartre are already in this novelette. And the main hero’s obsession with necrophilia symbolizes an abhorrence of the pending stream of death.In front of them, their leader – a degenerately skinny kid with the sulky face of a fish – kept time with a long drum major's stick. He held this stick obscenely erect, with the knob at his crotch, it then looked like a monstrous monkey's penis that had been decorated with braids of coloured cord. Like a dirty little brute, he would then jerk the stick level with his mouth; from crotch to mouth, from mouth to crotch, each rise and fall jerking to a grinding salvo from the drums. The sight was obscene. It was terrifying – if I hadn't been blessed with exceptional composure, how could I have stood and looked at these hateful automatons as calmly as if I were facing a stone wall? Each peal of music in the night was an incantatory summons to war and murder. The drum rolls were raised to their paroxysm in the expectation of an ultimate release in bloody salvos of artillery. I looked into the distance... a children's army in battle order. They were motionless, nonetheless, but in a trance. I saw them, so near me, entranced by a longing to meet their death, hallucinated by the endless fields where they would one day advance, laughing in the sunlight, leaving the dead and the dying behind them.

The tale is prophetic. In the tumultuous times hysteria prevails. -

In a time and place of fear there is often a self portrait that emerges that can no longer be hidden - and this is the true 'us' who we did not want others to see. Excellent examination of that which we hide - but that emerges in times of conflict. A haunting story that will stay with you.

-

Much preferred this to 'Histoire de l'œil' (Story of the Eye). I found it, to my surprise, to be a quite brilliant novel. Starting off in London, before taking in Paris, Barcelona, and briefly towards the end, Germany, all set around the time of the Spanish Civil War, Blue of Noon bizarrely felt just as much to me like Hemingway as it did likes of Céline or Henry Miller. There are nods towards Sartre too, who was a fan of the book. It's bombarded with an acute nihilism, and lots of crying and moping, and our protagonist Troppman having a morbid fascination with corpses, as well as being drunk and sick most of the time. Bataille really captures that brooding feeling within his narrative in regards the years leading up to the Second World War, with Europe on a cliff edge, and he builds a pensive tension leading towards it's haunting ending. Expanding on that, Blue of Noon had some of the most beautiful depictions of sorrow and despair that I've come across.

The eroticism is toned down, the psychology is turned up, as Troppman slowly starts to creep into the shadows of rising fascism, who, during his stay in the places I mentioned above, spends time in the company of four woman: Dirty, the Marxist Jew Lazare, the young Xenie, and his wife Edith. Abomination would be one word I'd use when describing the thoughts of some it's character's, especially Troppman who seems to drift through the darkness of a decadent world worthy of a good scrubbing, and in an alcohol haze he tries to find a cause to devote himself to, but illness, lethargy and repulsion follows his path of righteousness. What is worth saying also, is that Bataille has the ability to incite a physical revolt in the reader as we accompany Troppman on his journey. I will now certainly read more Bataille. Maybe some non-ficton next. -

4.5 stars. Bleak, depraved, and nihilistic, but in an utterly gorgeous, razor-sharp way. Far more potent and incisive than his Story of the Eye. Absolutely loved it.

-

A gruesome premonition. Written in 1935 and quickly superceded by events that left it unpublished for 20 years, this is a record and product of a collective (erotic?) death drive gripping interwar Europe. We all know where it lead, but the feverish personal-political particulars are all the more haunting for cutting off before. I was gripped with nausea as I read this today, and though I don't think this was in any way caused by the book, it seemed the appropriate state in which to fall into it, and I pressed on through the discomfort.

-

Of this I am sure: only an intolerable, impossible ordeal can give an author the means of achieving that wide-ranging vision that readers weary of the narrow limitations imposed by convention are waiting for.

(Georges Bataille, Author’s Foreword, 1957.)

In Blue of Noon as in all his fictions – though, to my knowledge, Blue of Noon is his most explicitly personal – Georges Bataille put his money where his mouth was. Agree with his manifesto or not (and I’ll admit the older I get the more restrictive it seems, the less adventurous, the less admirable) you can’t miss his singleminded dedication to it, which gives his best work a thrust normally felt in thrillers, though it is powered almost entirely by this strange writer’s obsessions. True, it’s not just the suffering but his warped take on sex that’ll compell you, but in Blue of Noon, like Hitchcock, he seems to have perfected unseen-fuelled suspense, and there’s no need to explicate what is manifest in his characters’ actions.In London, in a cellar, in a neighbourhood dive – the most squalid of unlikely places – Dirty was drunk. Utterly so. I was next to her (my hand was still bandaged from being cut by a broken glass). Dirty that day was wearing a sumptuous evening gown (I was unshaven and unkempt). As she stretched her long legs, she went into a violent convulsion. The place was crowded with men, and their eyes were getting ominous; the eyes of these perplexed men recalled spent cigars. [...] Drunkenness had committed us to dereliction, in pursuit of some grim response to the grimmest of compulsions.

What I love about Bataille is his clearsightedness. And his resolve: to tell the truth about the processes at work on his dissolute narrator (a truth which we presume, and Bataille does as much as acknowledge, he could only know by having endured it) even at the nadir of that barely-sketched character’s infamy. Blue of Noon revolves around the axis of humiliation. In scene after scene we witness the urge to humiliate in the hurt and unhappy – in the narrator (Troppmann), whose failed marriage has led him via a series of prostitutes to an impotent codependence with the cruel but beautiful (or, in his eyes, beautiful because cruel) Dirty, and then into bored victimising of the lost Xenie. That despite himself he’s drawn also into the orbit of the would-be revolutionary Lazare (though more because he requires “a bird of ill omen” to keep him company than from any social conscience, which would be trite) seems merely another instance of his bullying, since one thing he knows in his bones is that Europe is doomed, and every time he purges himself in confession to this good Christian virgin he can’t help but shock her with doom-laden pronouncements out of shame at his own helplessness. It’s ugly, but powerful. He’s far, far from a hero, but equally no villain, no death’s head, no gargoyle. What Bataille does here – and I don’t think it’s been done often – is reveal just how vulnerable a cruel man can be. Sensitive too. And aware of his own cruelty. All of which just compounds his suffering.

For readers of the 2001 Penguin edition (and probably the 2012 edition), Will Self pens an impressive introduction, comparing the novel to an out-of-control car. “It is as if some cloaca God were to descend to someone who was labouring on the torture throne of constipation, and deliver them a laxative balm.” He also compares “Bataille’s own view of lust as an annihilator of human difference [...] to the way the Nazis’ lust for power threatened humanity with annihilation.” (Blue of Noon is set, in various European cities, in the lead-up to the Second World War.)

For those unfamiliar with Bataille, The Story of the Eye is (in English) his most famous work, though My Mother / Madame Edwarda / The Dead Man (a novel and two short works published by Marion Boyars in 1989 and 1995, and again by Penguin in 2012) is equally rich, startling and powerful. His Eroticism also comes highly recommended, but I started to grow away from his vision before I read it and have only revisited him recently from an urge to consolidate that period and set something of it in writing. Call him an influence but not a favourite. Brilliant because unique, because so few have attempted what he attempts. But doomed to circle the same terrain ad nauseum, much as it may be his own. -

17/09/2019

22:10 :

Bon... Il me faut encore du temps pour mettre en ordre mes idées et mes impressions sur celui-là... Ce livre me laisse la drôle d'impression d'être passé à travers. ... C'est rare qu'une lecture me laisse déconcerté comme ça.

23:45 :

Relu le livre en diagonale. La note de lecture est en route. Normalement c'est pour demain.

Sacrée lecture biscornue.

18/09/2019 :

11:20 :

SUJET :

La vie subjective de Troppmann, contemporain de la guerre civile espagnole (1936-1939).

Surtout, le besoin de Georges Bataille de se confier lourdement.

MON IMPRESSION :

D'entrée, je suis frappé par un mélange de beauté et d'abjection, de fulgurence et d'obscène, une lucidité délirante qui culmine dans des rêves de fièvre peuplés de chimères, d'orgies répugnantes, de statues du Commandeur chevalines et de tueurs à la lanterne.

C'est un enchaînement d'évènements sans causes et effets clairement établis, sans différence de fond entre ceux de la veille et ceux du sommeil. Une lecture cahoteuse comme un délire de fièvre.

L'intrigue, ou ce qui en tient lieu :

Troppmann est dans une situation personnelle compliquée. Il a abandonné sa femme Édith, mène une vie dissolue avec une femme "perdue de débauche", Dorothea, alias Dirty. Moralement, c'est l'anomie, notre sujet est dans une dérive totale. La situation, malaisée d'entrée, s'embrouille davantage pour devenir inextricable. La vie de Troppmann devient une dérision, un sabotage et une imposture cauchemardesque.

Dans cette errance sans ancrage, ni tout à fait volontaire, ni tout à fait subie de l'extérieur, ce qui reste, c'est le besoin de pouvoir sur les autres. La soif de blesser, le désir morbide de tyranniser et de se faire tyranniser pour se prouver qu'on existe.

1. Le bleu du ciel est un texte immédiat et étrange qui humilie la langue écrite.

La confession doit sortir, la parole coule comme le sang d'une blessure, comme de la sueur, un rot ou du vomi qui ruisselle.'Il y avait maintenant une fuite dans ma tête, tout ce que je pensais me fuyait. Je voulais dire une chose et, presque aussitôt, je n'avais plus rien à dire.' (p.96)

'Inutile de parler. Déjà les choses sont mortes, comme dans les rêves.' (p.101)

'Toutes choses commencèrent à se décrocher (...) il aurait fallu les fixer (...) aucun moyen. Mon existence s'en allait en morceaux comme une matière pourrie' (p.81)

2. Avec la défaite du langage, la souffrance reste le seul bien commun d'êtres opaques et inouïs les uns pour les autres.'- Je souffre. - Que puis-je faire ? - Rien.' (p.96)

3. Devenir pur spectateur et étranger à sa vie.'Je comprenais qu'à Barcelone, j'étais à l'extérieur des choses.'

À trois reprises, en rêve ou éveillé, Troppmann est témoin de révolutions :

Témoin de la Révolution russe dans le rêve de La Galerie de Machines, à Léningrad.

Témoin de la Guerre Civile espagnole, dans un quartier de Barcelone.

Témoin du bouleversement national-socialiste, de son incarnation dans les mouvements de jeunesses fascistes à Francfort.

Aussi bien, il reste spectateur passif. Ces Révolutions lui sont aussi étrangères que lui à lui-même. Troppmann se dit entraîné par les circonstances que dictent le sort.

Il y croit.

RÉFÉRENCES APPARENTÉES

Crime et Châtiment, Carnets du Sous-Sol, Les Démons- Dostoïevski

Le patronnage est reconnu dès la page 18

Dérision, on le trouve tout du long dans la soif d'expiation et la volupté d'anéantissement à différents degrés chez de tous les personnages.

Lazare, vampire laide et sale, l'ascète masochiste de la douleur, l'amie des pleurs, la sainte révolutionnaire fascinée par la mort ; M. Melou, le logicien rhéteur qui traite la mort de millions comme un problème de géom��trie ; Dirty et sa débauche ; Xénie et sa soif de sacrifice, Michel, dominé par Lazare et qui va se faire tuer dans la guerre urbaine à la demande de Xénie.

Ce monde d'anarchistes sinon de nihilistes évoque aussi The Secret Agent de Conrad, avec ses intellectuels délirants.

Il a aussi partie liée avec Les Chants de Maldoror de Lautréamont, pour leurs intrigues décousues, leurs visions opiacées et leurs rêves fiévreux.

Kafka.

Le Spleen de Paris - Baudelaire pour ses visions déréglées.

Pour la situation à l'origine de

La Nausée de Sartre, pour la passivité et l'impuissance qu'ils dépeignent.

'En fait d'être humain, décidément, j'étais injustifiable.' (p.122)

Et ce besoin de se projeter, de projeter ce qu'on porte en soi, pour survivre.

'J'avais besoin de ne plus m'occuper de moi. J'avais besoin de m'occuper des autres.'

Proche encore de

La déchéance d'un homme d'Osamu Dazaï. Désir d'avilissement, détermination d'aller à fond dans la débauche, la déroute, tous deux en parlent.

C'est le tableau d'état transitoires, sur un fond d'angoisse et de menace insaisissables, ces états équivoques où l'on veut ce qui nous dégoûte et où l'on a horreur de ce qui nous plaît, habituellement.

Les Diaboliques - Barbey d'Aurevilly

Pour leurs personnages de femmes fortes, sadiques ou masochistes, résolues, troubles. La scène d'amour macabre dans le cimetière de Trèves m'a beaucoup fait penser aux passages apocalyptiques dans ses romans, aussi.

Céline

Pour l'oralité, l'obscénité et le travestissement.

À Rebours - Huysmans

Pour le désœuvrement, le dégoût de vivre, l'esthétique décadente.

Pour les films,

L'échelle de Jacob

Abre los ojos -

May be three and half stars.

The rating here is very subjective. If, for instance, a person with the sufficient knowledge of the pre-war Europe along with its political turmoils and its popular philosophical ideologies, might end up liking it much better. And he/she might rate it highly.

Of course, I too did some extra reading. Searched for some of the definitions and features of Fascism, Spanish Civil War, the assassination of Dollfuss, etc. The reason for the extra reading: The novel is situated in a particular historical setting of Europe and the characters are allusions to various philosophical/political positions of the then Europe (Thanks to the introduction to Will Self). It was the time Fascism was gaining ground all over Europe.

The novel as such deals with a man and his amorous encounters with three women. The three women are supposed to be allusions to various ideologies. For instance, Dirty (Dorathea) is an allusion to the past regime or the regime that is to be thrown away. And so, calling her as Dirty is intentional (to me it looks like that). The past regime is one to which mud is slung. It is always dirty. And it has to be replaced with the new government and even if it is needed to be arrived at with the violent means, it is okay. This position is represented by Lazare, the second woman. Here too, the name is very suggestive. Dead man alive - Marxist ideology of salvation through violence is questioned (?). Or Marxist ideology itself is shown to be redundant. The other woman is Xenie, who represents bourgeois class.

The main character in the novel is attracted to all three and he can not decide where to place his trust. He is indecisive. He is content at times being with Lazare (Marxism/Fascism) and the next moment he has a longing for Dirty and he also flirts with Xenie. If that is the case, the novel has come out well.

I sincerely hope that I got the point. -

To a greater or lesser extent, everyone depends on stories, on novels, to discover the manifold truth of life. Only such stories, read sometimes in a trance, have the power to confront a person with his fate. This is why we must keep passionately striving after what constitutes a story: how should we orient our efforts to renew or, rather, to perpetuate the novel?

A story that reveals the possibilities of life is not necessarily an appeal; but it does appeal to a moment of fury without which its author would remain blind to these possibilities, which are those of excess. -

A gruelling story set in the turmoil of the 1930s. The story takes us on a journey of sexual depravity and excess with the rise of Fascism before the second world war. If is about the main character Troppmann who is out of control drinks drinking to excess and having affairs. womanises and is on the verge of despair. His wife Dirty leaves him for Brighton and he goes to Paris to go on a bender to end all benders.

Not an easy story to read and you need a shower after reading it. The characters are mostly sinking into drunken chaos with no future. The goal appearing to be trying to drink yourself to death while being as deprive as possible. A story of losing yourself to madness before the horrors of the Second World War. -

Não. Georges Bataille não é para mim. Pelo menos O Azul do Céu.

Excepto o título, tudo é negro neste livro:

Uma alcoólica (chamada Dirty) que não controla o sistema digestivo ("superior e inferior");

Um homem que descobre ser necrófilo quando vê o cadáver da mãe;

Cenas de sexo em cemitérios;

E mais umas coisas que já esqueci...

Nada disto me impressionou, apenas me enfastiou. Ou estou a ficar perversa, ou não entendi nada. Espero que a segunda hipótese seja a certa...

(Na parte final tem uma referência ao Nazismo, mas já não me interessou fazer a ligação aos acontecimentos do cemitério e da taberna...) -

I've read this book three weeks ago in scarce hours, but its female characters still haunt my mind - Lazare, Dirty. The book strongly reminded me of all the fiction I have read by Henry Miller, but it is far more elegant. The text is definetely kindred, my-poetry-like with this natural and bright promiscuity. Book includes several descriptions of somebody's or author's dreams. Intimate and not at all political, there's nothing radical in this book but its historical context barely dimly seen. Actually, I wonder if being a type of a person easily succumbing to ideas of alterations of social order - an activist - isn't merely a chemical gap between a human and what an addict of endorphin our body is at times. Out of sudden, the protagonist is ready to become a kamikaze for some underlit political purpose, although the whole narration danced around his love torments/adventures in fever. I feel like I could have written this too. I picked up this book in order to establish a link between eroticism and political engagement, however it seems like this is what the book is missing..

-

![Keith [on semi hiatus]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/users/1541020315i/84884940._UX200_CR0,0,200,200_.jpg)

I love this, I love it just as much as his Story of the Eye and My Mother/Madame Edwarda/The Dead Man story-set.

Albeit more grim and nihilistic than anything else of his that I've read thus far, I can see a maturation in this work of his compared to his others.

His eroticism days were not forgotten but simply put on lay-by for being placed in a more precise part of the story, and although the necrophilic talk was a bit much for me he does wrap it in such a poetic way that it doesn't overwhelm the story.

The relationships in Bataille's work are always of a deep nature as opposed to many other writers' scratch-the-surface works of erotica, and the detailing throughout is exceptionally vivid as always.

For me, personally, I've consumed enough of his work that I think it about time I got tucked into the biographical work that others have provided on him.

I'd suggest, for future Bataille fans, to leave this to last and get through My Mother/Madame Edwarda/The Dead Man first, followed by Story of the Eye, followed by this, but that could be my bias speaking. -

This is probably the least pornographic Bataille book I've read. Which means the kinky sex isn't constant, merely occasional.

When I read L'Histoire de l'Oeil, I was an acid-dropping 19 year old, and extremely receptive to all things transgressive and French. I was somewhat afraid that an older, soberer self would be unimpressed by Bataille. But, if anything, he's become more powerful. The Blue of Noon is a fairly remarkable, fairly funny novel about everything and nothing. And the ending... oh my, what a portent. -

3.5 stars. An unusual, clever, gruesome, grim, concisely written novella about idle, nihilistic Troppmann and his self destructive relationships with three women. Set in 1935, mostly in Europe, where Troppmann experiences the Catalan riots and the rise of Nazism in Germany. Troppmann narrates about his relationship with unattractive Lazare, submissive Xenia and deviant Dorothea (‘Dirty’). Troppmann writes about abusiveness, drunkenness, self harm, violence and perverseness.

-

Brief, but scarringly debauched reminiscences of a man and his self-destructive relationships with three women (ugly Lazare, submissive Xenia and perverted Dirty) set against the rise of Nazism and the Catalan riots in 1935. Abusive, drunken, dilettante Communism, self-harm and perverse (with even a touch of necrophilia thrown in), this is not for the faint hearted, but it is powerful, nihilistic fare and despite the gruesomeness of it all, I wanted to go straight back to read parts of it again, so it definitely has something.

-

‘To Neil,

Hopefully a more successful encounter than after ‘The Story of the Eye’

Love,

Sherilyn x’

The scrawled in message behind the front cover of my copy. Fuck you Neil. Fuck you Sherilyn. -

This was like a fever dream—a wonderful joyride on the train of imagination that takes you through highly personal emotional and sexual dramas, playing within the backdrop of epic conflicts that eventually came to shape our world as we know it today. As above, so below is one maxim that captures the idea of this novel: the macrocosm world of 20th century Europe began to mirror the microcosm world of the characters; each, in turn, influencing the other.

-

Abjection, as Julia Kristeva takes it, is a brilliant and flexible effect/behaviour which I can see fruitfully applied all over from Sebald to Butler & Deleuze but I think it bears the most weight when we retrofit it with Bataille. Abjection can disturb Eroticism in the act of jettison - discharge as a characteristic of mostly living bodies which extends and disrupts, appears as expulsion and entry. It also challenges the sharpness of the Bataillan Symbolic: what is the legitimacy of death as a fixed state? I think Blue of Noon is the text of Bataille's which most effectively anticipates the work of Kristeva. Here we have expulsion and objection and as many fluids as you like

It's frankly bizarre that this exists because it's a novel entirely shattered by the fact of its author's inability to comprehend his own experience, almost entirely because of the encounter with Weil, Lazare in the text. She strides into this and GB is shellshocked. What follows is a series of desperations, which is fairly par for the course with him but it's clear in this case that everything following their meeting is conditioned by her.

I don't mean to suggest that the book doesn't work. It does, and it's GB at a rather unique point of harmony between his novelistic grotuexcess and his theoretical work. It's that biographical twist that makes this unrepeatable. He makes himself escape -

Creo que el choque entre el poder -que es la muerte- y las fisuras del poder -donde resiste la vida- es estructural, inevitable, ubicuo. Por momentos, las fisuras tiemblan, se multiplican, se ramifican. En esos momentos, pasan cosas extrañas. Hay expansión de agonías, opresiones, perversiones, epifanías. El azul del cielo es una novela crónica de uno de esos momentos prerrevolucionarios. Está la Guerra Civil Española. El anarquismo sin fronteras que se reunió en Barcelona. Por eso se trata de un clima de época, pero también de patrones estéticos de quiebre que ocurren en otros momentos de efervescencia. Es una novela de pura pasión, de tanta intensidad que gasta rápido la vida. Es una novela erótica, perversa, política, filosófica. Hay mucho sexo, alcohol, vómito, asco y fascinación. Un protagonista reventado, Doppelgänger de Bataille, y tres mujeres. La más interesante es una versión literaria de Simone Weil. La más fea, que es a la vez la más atractiva. La mirada horizontal es de caos y dolor. La mirada vertical es tranquilidad. El cielo es azul. Es novela a-teológica.

-

The nature of hot sex and fascism via the eyes of the one and only Georges Bataille. Now here's a man who knew how to have a good time. One cannot seperate the politics from the sex. Is lust an individual desire or part of the whole picture?

-

Voornamelijk gelezen om te kunnen vergelijken met de vertaling van Cornips, uit '71. Enkele prachtige zinnen zijn door Cornips vele malen pakkender opgeschreven, maar ik heb me tijdens het lezen van dit boek zo laten ontroeren en meevoeren dat ik vermoed deze vertaling te durven verkiezen. Erg zwaarmoedig, soms frustrerend om te lezen, maar het heeft me eigenlijk geen moment losgelaten.

-

Went searching for a Bataille novel at my local library and this was the only one currently available; in retrospect, it probably wasn't a great place to start. The style and structure is fascinating--poetic, elliptical, potent, sometimes (often?) disturbing--but I could never muster up much interest in the subject matter, which is less about sexual politics (as Bataille is famous for) and more about the perils of fascism (though this often extends to sex in Bataille's vision). I've not given up on Bataille, quite the contrary actually, but despite the occasional moments of brilliance I had to admit this just didn't do a thing for me.

"I got out of the car and thus beheld the starry sky overhead. Twenty years later, the boy who used to stick himself with pens was standing under the sky in a foreign street where he had never been, waiting for some unknown, impossible event. There were stars: an infinity of stars. It was absurd--absurd enough to make you scream; but it was a hostile absurdity." -

Such gorgeous writing! Absolutely in love with Bataille! On to Nick Land's The Thirst for Annihilation. Bataille is one of those men you wish you had in your life, a distant cousin perhaps, or an unrequited love. And I'm so happy he gave a shoutout to Kafka in the appendix. So much alike, the two. And so very fascinating!

-

Histoire de l'oeil was quite a bit better; this one dragged on a bit. The last 35 pages or so, however, were sublime. Poor Xenie.

-

I have a tendency to choose short books of relatively low merit by famous authors in preference to their classic texts. This foible arises in part from a more general distrust of texts as guides to life really lived. The marginalia of 'great minds' often brings them down to earth and reminds one that little good work comes without much persistent labour. Persistent labour can, however, sometimes remove the authenticity of feeling that belongs to a particular age.

'Blue Noon' is typical of that sort of work that gets pushed late to the public when other work has brought a man to prominence. The author is both flattered and resigned. Bataille's curt foreward to the 1957 first edition of this 1935 novella tells us as much. Others have prevailed on him to publish the manuscript, he no longer thinks like the late thirty-something man he was then (he has, indeed, 'moved on' as we say now) and he tries to explain that the ham-fisted clumsy style of the work is deliberate (which at least relieves us from the mistake of blaming some hapless translator for its leaden sentences).

So why bother with the book? Try treating it as a companion piece to the Henry Miller rant that we reviewed at:

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/33... - two literary males trying to cope with a world where sex is pushed into the realm of the near-criminal and where both are trying to find a way of expressing their true natures. In this context, it is a social document of sorts, set amongst the bien-pensant prosperous and idle French middle classes of the 1930s who were adopting leftist views without enthusiasm or understanding and sensing the cataclysm to come.

Bataille was part of the Surrealist movement and the book is an uneasy marriage of dream sequence and realism - a brave attempt perhaps but unsatisfactory. And if Bataille is open about its clumsiness as a text, who are we to argue? The number of repetitions of the word 'ridiculous' alone are, well, ridiculous.

The hero is a whining, lacrymose, self-absorbed (apparently once self-harming) rather nasty, sickly, death-obsessed, depressive and mildly sadistic figure without character whose attempts to cope with a wife, a mistress, a mother-in-law, a lover and an odd sort of anti-woman, a political activist, are played out across Europe - London, Paris, Vienna, Catalonia (oh, how we miss Orwell's insights) and the Rhine Valley with a cast of walk on servants, gilded youth, anarchists, communists and young bright-eyed and bushy-tailed Nazis. Not forgetting a dream trip to the Soviet Union. All in under 130 pages!

The woman are not much better than our depressed and depressing hero. The wife with two kids left in Brighton and her mother come across as the most sympathetic characters probably because they are so thinly sketched. None are more than creatures of our 'hero's' tale. I may not always be the sharpest card in the deck when it comes to 'literature' but the obscurities and failures to communicate emotion, at least beyond the lachrymose and 'ridiculous', really do pall after a while.

The mistress and the lover are neurotic - the political activist cold and disturbed in an entirely different way as if a woman (or perhaps a man) who was not lachrymose, suicidal and lying wasted on their beds periodically was bound to become a political fanatic. Everyone is weak and moody. Yawn!

At one point we have the two neurotic women separately heading for Barcelona with the political activist in situ and what could have been a diverting comedy of manners or a tragedy of love turns into a rather dreary and sordid shuffling of persons around rooms while a general strike and some shooting goes on outside.

So why keep the book in the library? Because, as I noted above, it is striving to tell us something about the mind of the powerless lost souls of its time despite itself, about the ones who had no ideology and just wanted to live, but were surrounded by fanatics. The sex, by the way, is abrupt, honest in its way and real enough but don't let anyone sell this to you as under the counter pornography - the sex is just a metaphor for despair and rage and little more.

Now here's the spoiler because Bataille lets us into the secret of the book in a short exchange at the end:

Henri, listen - I know I'm a freak, but I sometimes wish there would be a war ...

This is a book about those who could see the cataclysm coming in the fanaticism of those around them and who just wanted the storm to break to put them out of their misery. To have something happen. Some would have actively sought war through fanaticism, whether that of the militarism of the Right or that of the reluctant revolutionary action of the Left, each feeding off the other, but the hysteria of the central character represents the real hysteria of the age - a shrill hope that the whole thing just go ahead because the tension was becoming unbearable!

No wonder that in 1957, our fifty-something writer wanted to make it clear that his opinion had changed - the bloodletting proved to be a lot nastier than anyone had envisaged.

Sartre wrote 'Nausea' in 1938 and, in addition to the general air of absurdity, there are moments when Bataille, in his observations of three years earlier, gets close to the imagery of the greater work. Since it is unlikely that Sartre read this work, either Bataille fiddled with the manuscript on the quiet later or this sense of 'nausea' (he uses the term) was widespread in European 'liberal' society. It is like the general air of despair amongst our middle classes as they contemplate the possibility that our society has broken down domestically as a result of the ideological 'war' betweem progressives and neo-liberals.

There is another reason to keep the book in the library - a few moments of brilliant clarity. Small sections - most notably at the very beginning and at the very end - give us small prose poems of desperate depravity that are filmic in quality. Another writer of the period bears comparison - Antonin Artaud, whose equally hysterical 'Heliogabulus' (reviewed rather negatively and not remaining in the library at

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/75... ).

Artaud and Bataille in this respect are two thin wedges from the past and the future respectively. Artaud writes as the last of the decadents and chooses an anti-modernist chaotic stance seeking to revel in the horrors to come and seeking comfort in insanity and paganism. Bataille writes as a confused Catholic-modernist and proto-existentialist avant la lettre periodically seeking immolation and death (albeit as a pose)as the tide of chaos created by competing rigid alternate conceptions of order rises.

Artaud is working in the context of dionysiac theatre and Bataille thinks like a post war film maker before his time. The presiding philosophers are a forgotten Nietzche and, despite a Catholic faith that is not present in this book, a Sartre yet to be discovered. The point here is that the marginalia of literature often conspires to give us a better picture of the stresses of society than the great works.

Artaud, Bataille and Miller are all, in their different ways, responding to a damaged failing bourgeois society that had repressed sexual passion and ecstasy. The failures saw this repression displaced into ideologies that competed to show off their ability to engage in violence for 'rational' ends. Things are much better now but the beast of psychic repression still lurks around our politics, waiting to return if it were but to be let it in.

So this unattactive self-indulgent short book has its small uses but reserve it for a day when you really have nothing much else to do. And, by the way, do not bother with the equally obscure and portentous 1982 introduction by Ken Hollings - life is short and you do not need to waste precious moments of your life trying to make sense of it. -

Very odd book. Took a while to catch the gist. Some context provided by a professor I met did help me understand this better. I was correct, as to the tradition, to connect this to Baudelaire. The Foreword by Bataille himself was enlightening, too, after having finished this read. This is one of the rare occasions on which it might have been better to actually read that before the book itself.

Definitely have not been reading much of the abject so far, but this is a good addition to the collection. Would add American Psycho to that category, although that somehow feels more like a thriller or detective. Would add Les Fleurs du Mal to that category, too, but its form is actually beautiful, whereas here the form is not (at least in translation). -

Un libro magnético, lo he disfrutado mucho y es de los pocos libros que después de leerlo tenía ganas de volver a leerlo de nuevo. Es breve pero tiene un poder de atracción muy grande. Me ha dado mucha curiosidad para conocer mas obras de George Bataille.

-

4.5. Most disturbing book I’ve read in a while. “The train lost no time in departing.”

-

Bataille, c'est l'obsession de l'érotisme et de la transgression dans un horizon de médiocrité, de petitesse et d'aigreur.

Comme il l'écrivait dans l'avant-propos à L'expérience intérieure :

« N'importe qui, sournoisement, voulant éviter de souffrir se confond avec le tout de l'univers, juge de chaque chose comme s'il l'était, de la même façon qu'il imagine au fond, ne jamais mourir. Ces illusions nuageuses, nous les recevons avec la vie comme un narcotique nécessaire à la supporter. Mais qu'en est-il de nous quand, désintoxiqués, nous apprenons ce que nous sommes? Perdus entre des bavards, dans une nuit où nous ne pouvons que haïr l'apparence de lumière qui vient des bavardages. »(10)

Cet état d'existence qu'il explore de manière qui paraît si authentique qu'il sera compris comme un malade nécessitant des soins par Breton (qui en a pourtant vu d'autres), voilà qu'il l'expose ici par le biais d'un roman au titre on ne peut plus trompeur.

Le titre est en effet l'antithèse du contenu de la trame principale du roman, consacrée à la noirceur la plus plate et déchéante qui soit.

Lorsque quelque chose comme un « ciel bleu » apparaît tout de même, c'est par le biais de personnages secondaires féminins qui croisent la route du personnage principal et à chaque fois, c'est pour être contaminé, sali, rabaissé et finalement rejeté à l'extérieur des possibilités actualisées par le personnage principal.

Manifestement, pour Bataille, la femme comporte quelque chose de beau, de bien, de saint qui doit être rabaissé, traîné dans la boue, maltraité. Chacune des femmes qui croise sa route est détentrice d'une qualité (beauté physique pour Dorothée (surnommée Dirty dans le roman)), empathie pour Xénie (nom qui évoque l'étranger, l'extérieur), implication politique idéaliste pour Lazare (qui ne ressuscite pas d'ailleurs) que le personnage s'ingénie à entraîner dans son désarrois vers quelques mauvais quarts d'heures de mal être profond.

Rien ne résume mieux le contenu du roman que la citation suivante :

« Un soir, à la lumière du gaz, j'avais levé mon pupitre devant moi. Personne ne pouvait me voir. J'avais saisi mon porte-plume, le tenant, dans le poing droit fermé, comme un couteau, je me donnai de grands coups de plume d'acier sur le dos de la main gauche et sur l'avant-bras. Pour voir... Pour voir, et encore : Je voulais m'endurcir contre la douleur. Je m'étais fait un certain nombre de blessures sales, moins rouges que noirâtres (à cause de l'encre). Ces petites blessures avaient la forme d'un croissant, qui avait en coupe la forme de la plume. »(149)

Ces méchants chapitres défilent en effet comme de petits coups sournois sur l'âme bonne, sur l'esprit serein, sur l'existence saine, pour en faire gicler le sang en le maculant d'encre noire et sale.

Bref, ce roman sans âme, souillé, rance, où la déchéance est si complète et dénuée de grandeur qu'elle en devient franchement ennuyante saura à coup sur affecter la bonne humeur la plus radieuse et ne décevra certainement pas son lecteur averti.