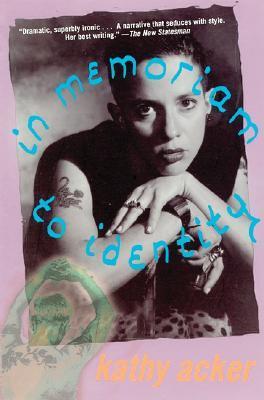

| Title | : | In Memoriam to Identity |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 080213579X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780802135797 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 272 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1990 |

In Memoriam to Identity Reviews

-

It's impossible to know a person who's always fantasizing about you and about whom you're obsessing.

Which is really to say: good luck knowing anyone, let alone yourself, except in some kind of unsatisfying antipodal self/other relationship—especially because the most rampant fantasy is that of the self, or the obsession of knowing another. So, the question here is an old one: What/who is the self? Who are we actually? What is love's purpose? Yeah, it sounds trite, but I guarantee there is no precedent for how this book is trying to talk about these questions.

A BRIEF LINEAR SYNOPSIS OF PLOT FOR THE PURPOSE OF CLARITY...

This question is dramatized through the repurposed biography/poetry of Rimbaud (or R) and his attempt to define himself through his love and boredom with (i.e., opposition to) society. If you didn't already know, he failed—abandoned poetry at 18, abandoned his oft-spurning lover, and abandoned himself to being a gun-runner and slavetrader in then-Abyssinia where years later he died, having never returned to poetry.

We then take up with Airplane, a girl bored by the Connecticut suburbs, her judgmental judicial father (mostly referred to as The Judge), who gets caught up with the first person that makes unwanted moves on her (who is also a reincarnated Rimbaud), ends up working a live sexshow, breaks up with R, and eventually lands in NYC as a writer of some kind involved with a German journalist Dom.

Alternated throughout the Airplane narrative is the repurposed narrative from Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury concerning the oft-mentioned and never heard-from Caddy, in this book almost exclusively referred to as Capitol. Important to note, this entire section is from her perspective, which lacks from Faulkner's. The narrative for her is much the same, just her side of it (oh and R is again reincarnated, here as Jason Compson), and when she runs away she too ends up in New York, trying to construct a self through making art out of disemboweled dolls, having failed (like R and Airplane) to make any kind of meaningful identity out of the people who she continually fucks. This artform finally gives her to herself: "because working... was her and her had never before been."

AND BUT SO

What we have is a reconstructed text on the always reconstructing concept of the self and identity. The last sentence of the book (spoiler [not like that ever matters with anything Acker writes]):

"Note: all the preceding has been taken from the poems of Arthur Rimbaud, the novels of William Faulkner, and biographical texts on Arthur Rimbaud and William Faulkner." This, of course, should be read in the same way as Deleuze and Guattari's "everywhere it is machines—real ones, not figurative ones"—which is to say, it is really both figurative and literal at the same time. Perhaps this would have been more helpful in the beginning, but that's the point, isn't it?

It is a very disorienting beginning, and the first section on Rimbaud that lasts about 100 pages will make you lose interest—power through. It reads better the second time after having finished the other two sections once the sparse discursive drops of insight have made you understand just what it is Acker is trying to get at. The Rimbaud section lays the basis for the failed attempts at establishing a self through relationship with another that will be seen again and again elsewhere.

Somewhere in the Capitol section, we are given: "We're not nothing. We're our stories." followed some forty pages later with the aside:"(Perhaps there are only stories and perhaps there aren't.)" There is quite a good deal of having it both ways here—quite a resistance to the stability of the text to even be comprehended. Everything is always broken apart to be reassembled whether it be the texts of R/Faulkner, or the characters' conceptions of their own selves—are they merely their memories? the people they fuck? merely the stinking meat of the physical which is the constant though alienated medium of access to the outside world from which they continually flee? simply ideological constructions in a novel used to make a point? It's really whatever you want as the reader given your own level of cynicism and/or patience for these kinds of textual and self-conscious post-modern efforts on the part of Acker. If it sounds like a drag from this review, turn back—this is not the book for you.

Surprisingly, the intertwined sections on Airplane and Capitol make for (dare I say) compelling character development, moreso than I have seen elsewhere in Acker, which is not to say they are "round characters," but neither are they flat. They inhabit the contradictory space of the self in their timeline in the novel (adolescence thru adulthood) that feels real, even tender. They do what they do because they do, and along the way they try to understand why. In some ways, even though they are cut-up stand-ins for the exploration of the theme of the self, they feel less deterministically bound than many more "round" characters from less self-conscious literature (ahem, Stephen Daedalus). Perhaps it is their instability that makes them relate, or their desire to know through the chaos of not.

Capitol, toward the end, changes her artistic methods. Instead of merely making the dolls cut open with guts hanging out, displaying fake interiority to what is obviously hollow, she now "smashed up dolls and remade the pieces, as one must remake oneself, into the most hideous abstract nonunderstandable conglomerations possible and certain people saw as beautiful." And here we have it—Acker's aesthetic in a nutshell. The move from the modern to the post-, and the conception of identity as elusive and everpresent—always somewhere hovering between memories and the stinking flesh. -

I love Ms Acker but this volume didn't quite hit the mark. Familiarity with Rimbaud and a better memory of Faulkner's Sound and the Fury should have bumped this up another star. As it is, no one writes like Acker. She has a pen that goes all the way through to the awful, traumatic core of being human.

-

Not sure why exactly but I found the first section of this 4-part novel weaker than most of Acker's work. Maybe I've heard it all before--so many punks and poets and punk poets are obsessed with Rimbaud and his crazy affair with Verlaine. Geeze, I hate to say it here in public and all but, well, the old gun-runner never did all that much for me--and I'm hard-pressed to care as much about writer's so-called lives as I am about their works. So, Acker's take, in her inimitable pornographic, terse-sentenced, and mixed POV style struck me as so much second hand news. (My favorite adaptation of this material is Richard Hell's utterly fabulous short novel Godlike, which transposes the story from 19th century France to 1970's New York City and makes the Verlaine figure the narrator. A fabulous piece of work--highly recommended.)

However, I found the second, third, and fourth sections of In Memoriam to Identity engrossing as hell. It feels like Acker's most self-reveletory novel--not sure if that's ironic given the title or if the title signals the end of the gesture. She often mixes snatches of her diaries into her literary appropriations but this one seemed heavier on the diaries and personal experience than on the appropriated voices of the Faulkner heroines and women in the author's life that she was appropriating. Two women, Airplane and Capital (the latter is also sometimes Caddy from The Sound and the Fury), plumb the depths of female sexuality, from incest to S & M through self destruction, desperate for love, sex, and survival. Classic Acker. Important ground for a female writer to cover and, I think, an amazing stylistic achievement in terms of freedom, readability, and sheer ballsyness.

Looking back from the end I can see how the Rimbaud material thematically links to Airplane and Capital's search for fulfillment through incest and S & M (as R. and V. searched for it through homosexuality, cruelty, and momentary rejection of bourgeois family life) but the first part wasn't half so personal, raw, or interesting to me as the rest. (This may also be because I just read Chris Kraus's biography of Acker so I was hyper-aware of the relationships the author was churning through in her journals that inform this particular novel.) -

I have dabbled in Kathy Acker before, having read Empire, Blood and Guts and Hannibal previously. This novel may be better than those, but for whatever reason, I didn't enjoy it nearly as much. One probable reason is the source material Acker is so famous for appropriating to her own ends; in this novel Rimbaud and Faulkner provide the base inspiration and I am really not familiar with either so most of its referential value was lost on me. And much like a tree falling in the forest, if the only value is in the references does the work have any intrinsic value at all?

The first section is the tedious whining, probably true to life, of Rimbaud as he tries to find his place in society while chasing after the guy he winds up stabbing in some French affair. Don't Care. Never cared about Rimbaud, don't care about Europeans and their American wannabees wearing leather jackets and smoking, discussing the philosophy of existentialism. I guess I prefer Dada to Kerouac, actual artistic production to preening for an audience, and while Rimbaud's poetry, the little familiarity I have, is fine and wonderful, his biography is uninteresting to me, and I feel that's what Acker is exploring here. Maybe gay identity tales were way more exciting before our enlightened age of 2015, where they seem to be just another part of the "coveted victim status" diversity pigpile.

The latter sections involve a New York artist moving from the worlds of art to prostitution to sex shows and back again, with apparently a backdrop of Faulknerian reference. So, read a bunch of Faulkner first if you want the full value. I basically just feel like I read a pretty close version of Acker's own biography and was not extremely interested in it. The older I get, the more I like writers who are able to project outside of their own lives, not endlessly rehash their own personal identity minutia, which seems to be what the worst of postmodernism devolved into. Which brings us to the title, In Memoriam to Identity. One can only hope. -

This one never entirely clicked with me. Had that Acker penchant for rawly presenting desire as a kind of brutal slave-master, but the literary references were lost on me. Started off making me think a lot and then slowly went downhill. Amidst all the rebellion, power trips, and libido, it still seems like a cry to be loved. To be vulnerable, open, and embraced by another with no fear of being hurt. I believe it was based on Rimbaud and also had something to do with Faulkner--I know the former because he was a character (or what masquerades as "character" in an Acker book), and the latter because it was mentioned on the back cover or something. My least favorite Acker book so far.

-

It almost sounds like the setup for an elaborate joke told in a depressing bar: what do Rimbaud and Verlaine, Faulkner's Compsons, and a stripper named Airplane have in common? (Punchline: ...)

Obsessive love is all over the place in literature and in literary lives, and Acker weaves a few of these stories together in her wise, chaotic way. There's something here about how we create ourselves, how we assemble identity, that "house into which you can enter, lock the door, shut the windows forever against all storms." (The experience of love--even or especially if it's a bad idea--can act as a catalyst for this, but suffering is not the only thing that can change a person.)

-

Brutal and cutting. Kathy Acker weaves a world of trauma, rejection, and disillusionment--but her characters don't accept their place in it. Using William Faulkner's works and Rimbaud as structuring figures, Acker explores the cyclical and cynical nature of identity, sexuality, and society.

-

Oh Kathy, you are the perfect sicko, rest in peace. Once I got past the first few brutal pages of Rimbaud fan fiction, I am always impressed by her ability to be both grotesque, illuminating, disturbing, and yet true in a weaving, complex, and vaguely philosophical style while talking about seedy, filthy, bizarre underworlds with characters who go by likes of "Capitol" or "Airplane."

-

this kinda... sucked? maybe i need to return to this when im older and wiser

-

...“You describe obsessive love as something you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemy”; Rimbaud + Verlaine, Airplane, Capitol.

"From a mansion built out of bone an unknown music comes. The legends of jazz and angels turn in the air like banners and the streets are so full of life, they throw themselves through the metropolis. The paradise of nihilism, of the apocalypse, has gone away. Primitives now jerk their bodies for the feast of the night. One evening I descended into the hiphop of Broadway, tiny skeleton watches sold in every dime shop, when funk bands on every corner gave me their names, the new work, under a skyless night, no longer able to escape the myth which told me who I was."

"To write is not to record or represent a given action, but to lose one's capacity to be the subject or initiator of that action. I lose myself, in putting down memories, in writing, but I don't escape the fatality of events, their weight and their irreversibility, merely because I cannot claim them for myself. What happens to me happens to no one, because what happens is my exclusion from what is happening. I am no longer able to participate in transformation: Stuck; stuck in prison; pain."

"(Perhaps there are only stories and perhaps there aren't.)"

"I can't forget love because I can't forget the pain, all that he taught me, that a human being can lie to another human being and know full well that he's or she's lying. Love dies. Like that. He left me. Lie like leave. Reject. Therefore judge. My whole life is not touching and being touched, but my memory of how I failed in what is most important of all.

Is the memory of love enough?

(In the face of death.)

Sure I remember every fucking detail the smell of the flesh on his shoulders the smell of his flesh's sweat when he was lying next to me on a bed, looking away, at night, not thinking about or even noticing me. Then. If I don't remember the details, I make them up, and what's the difference?

I could live in memories of him, what I have made up, as if they are a castle. A desolate castle. But (not only do I not know what I'm making up), there is nothing to hold on to. On reversed. That's probably the saddest, not death, but the nothingness everybody now seems to want.

I could be talking about the disappearance of history, our public memory, because they're trying. Money instead of history.

But memory is not enough.

All memory can do is a scream to be touched."

"Fuck you," said aloud. "The waste isn't just me. It's not waste. It's as if there's a territory. The roads carved in territory, the only known, are memories. Carved again and again into ruts like wounds that don't heal when you touch them but grow. Since all the rest is unknown, throw what is known away.

"Sexuality," she said, "sexuality." -

"She took out a cigarette because she didn't want to go near the despair, not yet. Since her hands were shaking, the cigarette calmed her because to light it her hands would have to stop convulsing. So a cigarette went between two lips and hung there because it took two hands to light it. A single lance of fire. Left a track of smoke. The smoke, moving into the throat, hurt there. Tasted something like rancid. Put the cigarette anyway."

Classic Acker who expresses herself in a way that is simultaneously zealously incoherent and resoundingly cogent. Many passages are dear to my heart and definitely hit home for me, but it didn’t pack the same punch as ‘Blood and Guts.’ The focus on identity and its fractured nature tends to distract and digress... but perhaps that’s just because the source materials (Faulkner and Rimbaud) are not in any way my favorite writers.

The Rimbaud section was the best part of the book for me because of its visceral dissection into familial relations, paternal (or in this case, maternal) disidentification and the desperate yearning for the absent father; similar themes run throughout the narrative which makes the piece as a whole a little repetitive.

The narrative, or style of narration, also lacked the variation and playfulness of ‘Blood and Guts.’ The grief and resentful are present, dense, and acute, yet somehow overwrought for this reason.

I can’t help but have a soft spot for Acker because of the material she deals with — dysfunctional, fractured family structures, desperate yearning for love and affection and attention, an almost compulsive or addictive desire for sex and physical intimacy, and, above all, the self-loathe and confusion that such a destructive lifestyle brings. In many ways the crude, uncouth, scattered style of writing that Kathy breathes resonates with me, and hums in concert with the content of her text; however, this book definitely wore me down, and made me wonder why Kathy, such an extraordinarily talented voice, refuses to deviate from the basics of a queer woman’s embodied (sexual) identity, in a book that is explicitly about the multifaceted, mishmashed nature of identity. -

Is Kathy Acker something like the female counterpart to William Burroughs? What an audacious writer! What a punk rocker.

I don't think I've read anything that delivers quite like this one. The sentences are broken more often than not. Pronouns are often skipped over. Character names change as quickly as points of view. It's sort of dizzying, but dazzling as well.

I think this is also the most sexually upfront book by a woman that I've read. DiPrima's memoir comes next, I'd say.

Recommended for people who like to use "suicide" as a verb rather than a noun. -

Better than Lolita

-

"Women need to become literary 'criminals,' break the literary laws and reinvent their own, because the established laws prevent women from presenting the reality of their lives."

Kathy Acker blows me away. She has influenced many writers, and is among the most important postmodernist authors. Her writing is a mix of obscenity, violence, and literariness.

"In Memoriam to Identity" (1990) is inspired by the writings and lives of Rimbaud and Faulkner; in one passage, she rewrites Faulkner's "The Story of Temple Drake;" in another, she retells the relationship between Rimbaud and Verlaine.

Her writing is challenging. She ignores rules of story, grammar, punctuation, and good manners. It is immediate, as if she wrote in an automatic way, spewing out thoughts, obscenities, ideas, scenes, memories, knowledge, nonsense. Here's a passage from "In Memoriam to Identity:"

********

"R[imbaud] wrote Delahaye about all that had happened to him and what he, R, wanted:

My friend,

You're eating white flour and mud in your pigsty. I don't miss Charleville. I don't miss being a bored pig where the sun dries up all brains but sloth. Your brains or feelings're being dried up: dead pig Delahaye.

Emotions are the movers of this world.

Me: I'm thirsty. What I'm thirsty for—whom I'm thirsty for—I can't get so I drink poisons. I've got to free myself. From what? Pain? Oh—for more poisons. Maybe more poisons'll come and I'll go so far, I'll emerge. Something is trying to emerge from this mess.

I don't know how.

********

Acker used literature to rebel against everything. She wrote, "Literature is that which denounces and slashes apart the repressing machine at the level of the signified." -

Death is a lizard that basks in the sun.

Unrateable.

If I hadn’t brought this book out on a state (of matter) sanctioned reading-date to Christian cult cafe, I probably wouldn’t have made it past the first few pages.

The parts of this book I loved, I’d carve in full into my skin, the parts that dragged on, dragged forever. Approximate half is the former , and second is the later. So it goes.

There is something Kathy understands, scorns and perpetrates that I couldn’t possibly imagine anyone else equally understanding, scorning and perpetrating. A constant remastering of collective trauma and sexual repulsion. What a trip! Thanks for it. -

I couldn't quite grasp onto these characters like I wanted to. The writing style took me a bit to get into, and by then I was finding stories/ideas/passages very boring. It is a difficult read in the sense that the characters are difficult (for me), but I appreciate the writing and tone of the book.

-

A couple of the ideas that stood out to me was the concept of self annihilation in carnal union with another. Also that there are people-types that transcend time and manifest in endless cycles- the same in the new and the new in the same.

-

I realize this isn't Acker's most popular novel, but this always resonated with me and I always thought it was a strong piece. Remains my favorite of her works.

-

A Great Work (all the caps).

-

kathy acker at her best. lots of violence and sex (as always) and demonstrative of acker's mastery at using the psychological and interpersonal as metaphor for socio-political issues, and socio-political issues as metaphor for the psychological and interpersonal. it's certainly more accessible than "blood and guts" but still deliciously abstract and nonlinear. "rimbaud" might be her finest piece.

-

I found this book much more approachable than Acker's other work, as approachable as anything by Acker can be. There is always some recoil. This one, though there were still multiple linked story lines, was easier and less strange on the surface to follow. The complexity of ideas is still there, but it's shifted a bit more off the direct surface. I got into this one more from that standpoint at least, though the weirder texts have other thugs I did get into.

-

I absolutely love Kathy Acker. As usual Acker gives us a dose of gender subversion through the medium of gutter-punk Genet gloriousness. This book is a very intelligent feminist reading of Faulkner and Rimbaud. A rumination on the subject of identity, seuality and history, this book is both thought-provoking and enjoyable. Highly reccomended.

-

Acquired Nov 20, 2006

Powell's City of Books, Portland, OR -

Gertrude Stein for contemporaries minus the American individualism and genius.

-

I think once I read Verlaine and Rimbaud I'll come back to this. A postmodern challenge of wits, some spectacular and haunting imagery, but not enough graspable "so what"

-

In memoriam to identity by Kathy Acker (1990)