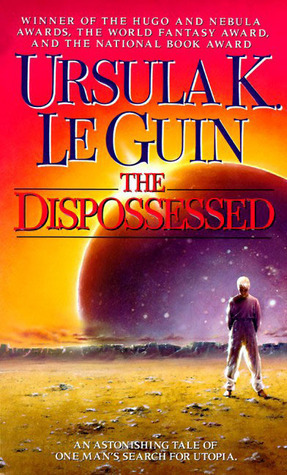

| Title | : | The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 387 |

| Publication | : | First published May 1, 1974 |

| Awards | : | Hugo Award Best Novel (1975), Nebula Award Best Novel (1974), Prometheus Hall of Fame Award (1993), Locus Award Best Novel (1975), Jupiter Award Best Novel (1975), John W. Campbell Memorial Award Best Science Fiction Novel (1975), Ditmar Award Best International Long Fiction (1975), Premi Ictineu Millor novel·la traduïda (2019) |

The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia Reviews

-

First of all: if you haven't already read The Dispossessed, then do so. Somehow, probably because it comes with an SF sticker, it isn't yet officially labeled as one of the great novels of the 20th century. They're going to fix that eventually, so why not get in ahead of the crowd? It's not just a terrific story; it might change your life. Ursula Le Guin is saying some pretty important stuff here.

So, what is it she's saying that's so important? I've read the book several times since I first came across it as a teenager, and my perception of it has changed over time. There's more than one layer, and I, at least, didn't immediately realize that. On the surface, the first thing you notice is the setting. She is presenting a genuinely credible anarchist utopia. Most utopias are irritating or just plain silly. You read them, and at best you shake your head and wish that people actually were like that; or, more likely, you wonder how the author can be quite so deluded. This one's different. Le Guin has thought about it a lot, and taken into account the obvious fact that people are often selfish and stupid. You feel that her anarchist society actually could work; it doesn't work all the time, and there are things about it that you see are going to cause problems. But, like the US Constitution (one of my favorite utopian documents) it seems to have the necessary flexibility and groundedness that allow it to adapt to changing circumstances and survive. She's done a good job, and you can't help admiring the brave and kind Annaresti.

Another thing you're immediately impressed by is the central character, Shevek. Looking at the other reviews, everyone loves Shevek. I love him too. He's one of the most convincing fictional scientists I know; I'm a scientist myself, so I'm very sensitive to the nuances. Like his society, he's not in any way perfect, and his life is a long struggle to try and understand the secrets of temporal physics, which he often feels are completely beyond him. I was impressed by the alien science; she gives you just the right amount of background that it feels credible, but not so much that you're tempted to nit-pick the details. You're swept up in his quest to unify Sequency and Simultaneity, without ever needing to know exactly what they are. And his relationship with Takver is a great love story, with some wonderfully moving scenes. There's one line in particular which, despite being utterly simple and understated, never fails to bring tears to my eyes. As you also see in The Lathe of Heaven, Le Guin knows about love.

What I've said so far would already be enough to qualify this as a good book that was absolutely worth reading. What I think makes it a great book is her analysis of the concept of freedom. There are so many other interesting things to look at that at first you don't quite notice it, but to me it's the core of the novel. What does it mean to be truly free? At first, you think that the Annaresti have already achieved that; it's just a question of having the right social structures. But after a while you see that it's not nearly as straightforward as you first imagined. Real freedom means that you have to be able to challenge the beliefs of the people around you when they conflict with what you, yourself, truly believe, and that can be painful for everyone. But it's essential, and it's particularly essential if you want to be a scientist; I know this from personal experience. Another theme that suffuses the book is the concept of the Promise. If you can't make and keep promises, then you have no influence on the future; you are locked in the present. But promising something also binds your future self. There are some deep paradoxes here. The book folds the arguments unobtrusively into the narrative, and never shoves them in your face, but after a while you see that they are what tie all the strands together: the anarchist society, the science, the love story, the politics.

It's a much deeper book than you first realize. As I said, it might change your life. It's changed mine. -

There are some books that even with my untrained, unskilled and inexperienced eye can detect and confirm are true works of art, mastery in literature.

Other works, perhaps less skillfully written or not as masterfully created, still strike a chord within me and I can grasp the vision and voice of the author as if we were friends, as if we shared a thought. It is truly rare when I can see that a book is both a work of art and that also touches me in a way that leaves a mark on my soul, perhaps even changing my life, that I can look back and see that my path changed after reading.

The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin is such a work, a true masterpiece of literature, science fiction or not, that truly touched me. I cannot say that it has changed my life, though, but rather affirmed some deep-set values and ideals that I hold. This really transcends the genre and stands alone as a work of art.

Science fiction may be best as a vehicle for allegory, for a way in which an artist can attach to an imagination or fantasy an idea or observation about our world that can only be grasped in the peripheral, can only be explained in metaphor and parable. Le Guin has here accomplished the creation of a minimalistic, austere voice of one crying out in the wilderness.

Beautifully written, this can be subtlety brilliant and painfully clear, some scenes left me unable to go on, yet I was compelled, entranced and beckoned to continue. Yet all the same, I was saddened to come to its conclusion.

******** 2017 Reread.

“Freedom is never very safe”

I’ve read over 1200 books in my life and have designated 6 as my all-time favorites. This is one.

The great thing about revisiting a work of literature is to notice greater detail the second time around. I was again struck by Le Guin’s beautiful writing and her carefully expressive style, but this time I paid more attention to the radical, revolutionary themes upon which she focused. And this is not a dystopian novel as we have become accustomed in the last few years, but an examination of a utopian model.

Anarres and Urras, twin planets in the Tau Ceti system, Urras having been colonized with humans by the Hain ages ago. Then Odo, a visionary who is imprisoned for her world-shattering ideas. Odo rejected the tenants of aristocracy, of capitalism, of property altogether. She espoused an anarchistic ideology, a utopian society without laws, money, or property rights. Those following Odo left the paradise of Urras with its fertile valleys and rich natural resources, for the harsh, dry mining colony on Anarres, sort of a moon to Urras.

Le Guin’s story begins about 160 later, with generations of the Odo revolution having grown up in this closed society. They’ve developed their own language which has no concept of property rights, or money, or many of the elements of our society has that we take for granted. The planetary truce is maintained as a fragile economic alliance: The Anarres citizens produce mineral wealth in exchange for imported goods from Urras. There is one space port, outlined by a simple low wall, the Anaresans don’t leave and the people from Urras don’t stay. The Anarres anarchist society is closed and fragile. The anarchists work together and toil for the common good, avoiding actions that would be considered “propertarian” or “egoist”. It is a primitive collectivism without central authority.

Shevek, a brilliant physicist (and I think one of the great SF characters) risks everything to travel to Urras and share with them his theories on temporal physics. This theory will lead to the development of the ansible. Shevek experiences the vast differences between the two societies.

The socio-economic dialogue that fills much of this novel is provocative and solicitous. Le Guin, very much affected by the turmoil of the Vietnam war, has crafted a brilliant story of revolution and practical utopia. The themes of revolution and idealism contrasted against an established power structure also made me think of Boris Pasternak’s

Doctor Zhivago as well as the 1965 David Lean film starring Omar Sharif and Julie Christie. Le Guin has the Anaresans portrayed as a peaceful people, with only the barest of defense against the powerful Urras governments, truculent and power hungry. The scene where Shevek marches with a crowd of disaffected Urras citizens was brutally reminiscent of a similar scene from Lean’s Zhivago.

Finally, and this is a superficial and trivial thought, but if I were to film this and pick a cast, I would have Viggo Mortenson as Shevek. I would also have interuldes of thoughtful quotes from Odo and I would have Ursula K. Le Guin herself fill that role.

Simply brilliant.

“His hands were empty as they had always been”

**** 2021 reread –

“We have nothing but our freedom. We have nothing to give you but your own freedom. We have no law but the single principle of mutual aid between individuals. We have no government but the single principle of free association. We have no states, no nations, no presidents, no premiers, no chiefs, no generals, no bosses, no bankers, no landlords, no wages, no charity, no police, no soldiers, no wars. Nor do we have much else. We are sharers, not owners. We are not prosperous. None of us is rich. None of us is powerful. If it is Anarres you want, if it is the future you seek, then I tell you that you must come to it with empty hands. You must come to it alone, and naked, as the child comes into the world, into his future, without any past, without any property, wholly dependent on other people for his life. You cannot take what you have not given, and you must give yourself. You cannot buy the Revolution. You cannot make the Revolution. You can only be the Revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”

This time I focused on the philosophy of the Odonians who inhabit the harsh moon colony of Anarres. Odo, who lived and died two centuries before the story begins, was a political dissident who taught and espoused a theory of non-authoritarian communism that in its expression was anarchistic. There are no laws on Annares, people work together out of an adherence to the Odonian principle of mutual aid. When Shevek visits Urras and observes the three different states and how, though materially far more rich than poor Annares, their lives are not as full.

“We don’t leave Anarres, because we are Anarres. But are we kept here by force? What force—what laws, governments, police? None. Simply our own being, our nature as Odonians. It’s your nature to be Tirin, and my nature to be Shevek, and our common nature to be Odonians, responsible to one another. And that responsibility is our freedom. To avoid it would be to lose our freedom. Would you really like to live in a society where you had no responsibility and no freedom, no choice, only the false option of obedience to the law, or disobedience followed by punishment? Would you really want to go live in a prison?”

This is a modern utopian narrative but unlike other paradisial stories, LeGuin is careful to note the good and the bad. As a Terran ambassador notes, the people on Urras have many blessings and though they may not have the spiritual maturity of the Odonians, neither are they that bad off. Conversely, the anarchists on Annares are free, but have little else, theirs is a poor, difficult life and they are only kept fervent by their devotion to Odo, in one sense keeping the revolution going. Also, LeGuin notes that in spite of attempts to restrict any form of government, bureaucracy or compulsion, some laws and restrictions creep into society anyway.

I read that another favorite author, Theodore Sturgeon wrote that The Dispossessed is "a beautifully written, beautifully composed book", saying "it performs one of science fiction's prime functions, which is to create another kind of social system to see how it would work. Or if it would work."

-

Oh, Ursula. No longer will I love you in a vaguely ashamed manner, skulking through chesty-women-blow-shit-up-also-monster! book covers in the sci-fi/fantasy aisles with a moderate velocity as though I am actually trying to find Civil War biographies but am amusingly lost amongst all these shelves, that's so like me, need a GPS for Borders. Today, I will begin loving you publicly, proudly, for you are the Anti-Ayn Rand. You do not skullf**k Ayn Rand and make her your bitch, no, too easy. You take her gently by the hand, lay down beside her pruned, mummified body and have entirely consensual, non-hierarchical, process-centered sexual intercourse like a paragon of second-wave lesbian feminism.

Ursula, you make me want to be a straighter man. -

‘You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.’

Reading The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin was likely the biggest literary event of the year for me. This endlessly quotable book gripped me on every level and the way Le Guin can examine and explain ideas is so fluid, especially how she crafts such functioning worlds for her characters and ideas to move around in. Told in a rotating timeline with the past events catching up to those in the present (a narrative structure that functions as an expression of several of the book’s themes), we follow Shevek’s life as a physicist growing up in a anarchist-style society and then his time on a highly capitalist society on the planet Urras as he struggles to develop a working theory of time that incorporates both cyclical and linear time. Shevek’s experience juxtaposes the two societies as he realizes his ideas can be very dangerous in a society that only values profit and power. So many intelligent discussions of this book already exist that I likely have nothing to add, but I love this book so much and wanted to get my thoughts down. Through exploring the multiple meanings of the word “revolution,” Le Guin explores society and sociolinguistics in this incredible book about freedom and sharing the struggles of others to help build a better world.

‘At present we seem only to write dystopias,’ Ursula K. Le Guin

wrote, ‘perhaps in order to be able to write a utopia we need to think yinly.’ She was speaking, of course, about the concept of yin and yang, something that seems present in much of her work and especially highlighted by the two societies in The Dispossessed. Le Guin contrasts two societies, the planet Urras full of war and stark inequality and the anarchist society that settled on the moon Anarres, and uses the juxtaposition to examine how to theorize on reconfiguring social systems to be ethical and free. Though as states the subtitle in original publications, this is An Ambiguous Utopia and Le Guin is not here to give answers but to tell a story within the landscape of these ethical musings, one that should give birth to further thought, further theory and further striving to better the world.

In

an interview with Anarcho Geek Review, Le Guin said ‘When I got the idea for The Dispossessed, the story I sketched out was all wrong, and I had to figure out what it really was about and what it needed. What it needed was first about a year of reading all the Utopias, and then another year or two of reading all the Anarchist writers.’ She admits the book is heavily based in the writings of

Lao Tzu (his book

Tao Te Ching has been translated by Le Guin),

Paul Goodman, and

Pyotr Kropotkin, though other anarchist thinkers such as

Emma Goldman and

Mikhail Bakunin seem to also inform many of the ideas present as well. Le Guin was heavily influenced in all her works by taoism, and

Paul Goodman’s work often showed taoism as a contributor towards a

coherent theory of anarchism. The Dispossessed details a style of taoist anarchism that is similar to those expressed in another Le Guin novel,

The Lathe of Heaven, one being that a revolution cannot rely on political or authorities but on a deep engagement between the individual and the world around us where we become the change we wish to see in the world.

‘The freedom to think involves the courage to stumble upon our demons.’

-

Simone Weil,

On the Abolition of All Political Parties

The change Shevek wishes to see originates in his work with time theories but he quickly realizes how immersed in political struggle his life is. Le Guin fans are treated to the creation of the ansible, a communication device that is present in the Hannish books, particularly

The Left Hand of Darkness, a device many players on the planet Urras are trying to help him create it but also to control it. His studies on time require him to combine two different concepts of time: Sequency and Simultaneity, with the former endorsing a linear concept of time and the latter for non-linear time, such as recursive theories. Shevek must transcend constructs that have been considered rational thought to a more radical theory of time, as a sort of postmodernist anarchist that must hold both modes of time in his mind at once in order to achieve his goal.

F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that ‘the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function,’ so I suppose we can rightfully claim Shevek as a genius here. His biggest hurdle, it would seem, is less the creation of his working theory but the hurdles of power. On Anarres he is stifled by others who can block his publication or wish to take the credit, while on Urras it will be used for profit, power, and likely warmaking.

‘Free your mind of the idea of deserving, the idea of earning, and you will begin to be able to think.’

Shevek’s Odian society on Anarres is set-up to have ‘ no law but the single principle of mutual aid between individuals,’ (

Mutual Aid by

Pyotr Kropotkin being an largely influential work in anarchist theory and this novel). It is a harsh planet where horizontal organization has kept the society going, with people assigned to rotating jobs to best befit the current needs to keep the society going. They have no sense of private property and everything is a community (even families where there are no individual family units). This contrasts with Urras, which is a capitalist society where profit and private property is the primary function (hence why the Odians refer to them as ‘propetarians’). While the harsh climate and scarcity of resources on Anarres may have been fertile soil for their style of society to work, they have developed a concept of communal society that see’s it’s function as one to remove unnecessary suffering.

‘We can't prevent suffering. This pain and that pain, yes, but not Pain. A society can only relieve social suffering - unnecessary suffering. The rest remains. The root, the reality.’

This contrasts with Urras where all the bad-faith bootstraps mythologies created a hierarchical society where chasing profits removes suffering from the elites but displaces it onto the lower classes, the very sort of thing the Odians fled to establish their society in the mining colonies on the moon Anarres.

‘To make a thief, make an owner; to create crime, create laws.’

-Odian teaching

‘The essential function of the state is to maintain the existing inequality’ wrote activist

Nicolas Walter in

About Anarchism, which is why Odians do not believe in any forms of State-ruled government. There are several different government styles on Urras, though Shevek sees them all as inevitable towards oppression. ‘The individual cannot bargain with the State,’ Shevek says, ‘the State recognizes no coinage but power: and it issues the coins itself.’ Even the thinly-disguised Soviet Russia country in the book (which is currently engaged in a proxy war with the strong capitalist country) repulses Shevek for still maintaining a government over the people telling their envoy ‘the revolution for justice which you began and then stopped halfway.’ Freedom, he argues, only comes from a collective society. To the idea of individualism, Shevek notes that what is society but a collective of individuals working towards a common goal.

'You put another lock on the door and call it democracy.'

While the glamour of Urras is charming to him at first, he begins to see how rotten it is at the core and how profit figures into everything, especially when his ideas are dismissed and questioned why he should be allowed to pursue them without a clear profit motive.‘There is nothing you can do that profit does not enter into, and fear of loss, and wish for power. You cannot say good morning without knowing which of you is 'superior' to the other, or trying to prove it. You cannot act like a brother to other people, you must manipulate them, or command them, or obey them, or trick them. You cannot touch another person, yet they will not leave you alone. There is no freedom.’

While Shevek sees that because his people own nothing, they are free, those of Urras only have the illusion of freedom, he discovers, and in their quest to own things are thereby owned by them. ‘They think if people can possess enough things they will be content to live in prison’ Shevek thinks. Interestingly enough, early in his youth he and his friends learned the concept of prison and decided to play-act it but the reader quickly realizes ‘it was playing them.’ They are so enticed into their roles they are okay with harming each other (‘they decided that Kadagv had asked for it’) which makes for excellent commentary on how hierarchy breeds violence and oppression.

‘All the operations of capitalism were as meaningless to him as the rites of a primitive religion as barbaric, as elaborate, and as unnecessary,’ Le Guin writes of our hero. To create this effect, Le Guin has done something extraordinary here by making sociolinguistics highly important to the novel as indicators of the different societies. Drawing on the

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that the structure of a language influences the native speaker’s perceptions and categorization of experiences. The linguistic relativity is seen in the Anarras language of Pravic, where there is an aversion to singular possessive pronouns since they imply property. Sadik (Shevek’s daughter) for instance, calls him The Father not, my father, or says ‘share the handkerchief I use’ instead of my handkerchief. The language removes a lot of ideas of shame and patriarchy as well. ‘Pravic was not a good swearing language. It is hard to swear when sex is not dirty and blashpemy does not exist.’

Even the language of Urras is alarming to Shevek. His language removes any class-based hierarchy, so prefixes such as being called Dr. are offensive to him. He notices that class dialects occur on Urras as well, with his servant, Efor, code-switching between them. THe upper classes on Urras tend to have a drawl to their words. Late in the novel when the Terran ambassador arrives (it’s a Hannish book, of course the Terrans show up), it is said of Pravic that it was ‘the only rationally invented language that has become the tongue of a great people.‘

Written in the 60s, the language aspects feel relevant to today’s world when there is much political discourse on the way language morphs with a changing society. Language and the way we apply it is culturally influenced, and linguistic signifiers can be reflective of culture, and there is often much argument online if adapting language to fit modern needs is social conditioning or simply just using the malleability of language to be more productive or empathetic in the rhetoric we choose to apply in various situations (Le Guin, for the record, frequently defended the singular ‘they’ in language [see the final question in the previously mentioned

interview]).

David Foster Wallace wrote at length in his essay

Authority & American Usage on social and political influences on debates over descriptive vs prescriptive grammar changes, and to see Le Guin incorporate sociolinguistics as signifiers for her two societies is quite wonderful.

‘I want the walls down. I want solidarity, human solidarity.’

The language barrier is a great example of how The Dispossessed toys with concepts of walls. The novel opens with a description of a wall and the question of how inside/outside being on of perception. Shevek frequently comments on how he wishes to tear down walls, and his message of revolution is not one of taking the power back but of abolition of power. No walls, no barriers, only unity. For that reason he cannot allow his device to be used for war, or nationalistic purposes as he realized those on Urras will want (he sees how racism occurs due to concepts of walls while there).’You the possessors are the possessed. You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in prison, die in prison. It is all I can see in your eyes—the wall, the wall!’

Revolution has many meanings in this novel. The overthrow of the system or a cycle such as his concept of time. But it is also shown that revolution isn’t a single act but a continuous cycle as well. The Terrans say they have seen it all, tried everything, but ‘if each life is not new, each single life, then why are we born.’ There must be a constant striving towards betterment, reshaping, undoing, rebuilding. Anarres is not perfect either, hence the ambiguous utopia, and there must be the drive to keep going. Hence the open ended conclusion to the novel.

'Society was not against them. It was for them; with them; it was them.'

The Dispossessed is such a magnificent work. The ideas are great, the writing is sharp and engaging, and there is an epic feel to the story as it draws on structures such as the hero’s quest. I love how Le Guin tends towards a style of storytelling via anthropology, and the political discourse in this only heightens my enjoyment of it. She was a brilliant writer and this book is such a powder keg of extraordinary thoughts wrapped in a a science fiction narrative. It is so endlessly quotable you could practically build a religion out of it. All the stars in the Goodreads cosmos aren’t enough to award this novel for how much I love it.

5/5

‘I come with empty hands and the desire to unbuild walls.’ -

Some books really make me think long and hard about life. This was one of them. I first inhaled it on a transatlantic flight a decade ago and felt that Le Guin, as usual, made my brain run on higher speed than it typically does. I was too intimidated for words back then, but I’ll try now, after a second, slower read spanning a couple of weeks, with time for brain to stop and think and really appreciate what I read.

“It’s always easier not to think for oneself. Find a nice safe hierarchy and settle in. Don’t make changes, don’t risk disapproval, don’t upset your syndics. It’s always easiest to let yourself be governed.”

It’s a perfect example of anthropological science fiction, the science fiction of big ideas, the one that focuses on exploring society and makes you think of uncomfortable questions that do not have satisfying answers - because life is like that.“Like all walls it was ambiguous, two-faced. What was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side of it you were on.”

(Image from

https://www.david-lupton.com/folio-so...)

The Dispossessed takes a close look at the questions too complex to dispose of in just a few words. The nature of relationship between individuals and community, the stagnation of political systems - be it plutocracy or anarcho-communism, the tyranny of majority and politicization of life, control of information flow and control of thoughts. How can you change status quo without arriving at the same oppression that necessitated the breakaway in the first place? How do you avoid the seemingly inevitable stagnation and bureaucracy? How do you separate and differentiate collectivism and conformity?“Well, this. That we’re ashamed to say we’ve refused a posting. That the social conscience completely dominates the individual conscience, instead of striking a balance with it. We don’t cooperate—we obey. We fear being outcast, being called lazy, dysfunctional, egoizing. We fear our neighbor’s opinion more than we respect our own freedom of choice. You don’t believe me, Tak, but try, just try stepping over the line, just in imagination, and see how you feel.“

And how do you even define freedom? How can people arrive at seemingly diametrally opposite ideas of what freedom means? And perhaps you indeed can only achieve true freedom when your hands are truly empty.“The wall shut in not only the landing field but also the ships that came down out of space, and the men that came on the ships, and the worlds they came from, and the rest of the universe. It enclosed the universe, leaving Anarres outside, free.

Looked at from the other side, the wall enclosed Anarres: the whole planet was inside it, a great prison camp, cut off from other worlds and other men, in quarantine.”

It’s slow and deliberate and meticulously laid out. There’s no burning passion, no unbridled idealism, none of the fiery outrage that would be so easy to fall back on for anyone less skilled than Le Guin. No, it’s a contemplative novel in which ideas are methodically explored. It is a book that rewards deliberate patience. It’s a book that does not provide a simple satisfaction of laying things as polarizingly good or bad, right or wrong; instead it presents multilayered complexity.“I never thought before,” said Tirin unruffled, “of the fact that there are people sitting on a hill, up there, on Urras, looking at Anarres, at us, and saying, ‘Look, there’s the Moon.’ Our earth is their Moon; our Moon is their earth.”

“Where, then, is Truth?” declaimed Bedap, and yawned.

“In the hill one happens to be sitting on,” said Tirin.

Anarres is the titular ambiguous utopia of individualistic collectivism (and no, it’s actually not that contradictory), which by necessity is rooted in scarcity — but there is egalitarianism even in that scarcity, as it’s not that people don’t go hungry, but “Nobody goes hungry while another eats” (really, a crucial distinction). It’s a harsh unfriendly place, a sister planet of Urras, a green paradise from which the anarchist settlers exiled themselves to make their own world with no laws and more tolerance and less oppression, becoming in that separated, alone, dispossessed — and hopefully free.“You can’t crush ideas by suppressing them. You can only crush them by ignoring them. By refusing to think, refusing to change.”

However, stagnation does not spare anyone, even supposedly government-less place with no laws — because judgmental uniformity and rigid dogma can overwhelm even seeming anarchistic freedom - “convention, moralism, fear of social ostracism, fear of being different, fear of being free!”.“We’ve let cooperation become obedience. On Urras they have government by the minority. Here we have government by the majority. But it is government! The social conscience isn’t a living thing any more, but a machine, a power machine, controlled by bureaucrats!”

It’s natural to seek answers to how it’s better than capitalistic or strong-state nations of Urras in collectivism, or how it’s worse than them in stifling individuality — but that’s not what Le Guin is doing here. No, she shows the true ambiguity of that utopia, the nitty-gritty of its inner workings, the harshness and the beauty, and the necessity of avoiding stagnation and complacency and consolidation of power.“We are brothers. We are brothers in what we share. In pain, which each of us must suffer alone, in hunger, in poverty, in hope, we know our brotherhood. We know it, because we have had to learn it. We know that there is no help for us but from one another, that no hand will save us if we do not reach out our hand. And the hand that you reach out is empty, as mine is. You have nothing. You possess nothing. You own nothing. You are free. All you have is what you are, and what you give.”

It’s easy to fall into a trap of idealizing one society and vilifying the other. Le Guin wrote Anarres as utopia - a fragile, flawed utopia, but utopia nevertheless, utopia compared to oligarchic plutocracy. But times change, values shift and adjust, and I realized how easy it is to start seeing the flaws of Anarres as so prominent, focus on the scarcity, the greyness, the conformity, the Soviet-like “-isms” in speech that sound so awkward. It’s easy to fall into the trap of seeing these flaws as the main point, as we have been raised on the specific view of individualism (not the collectivist sort that Le Guin presents) that prioritizes wants over needs. But just like Shevek, getting over the initial rose-covered view of lush green paradise, we can see the strange beauty even in the harshness, and the harshness in the beauty.“Because there is nothing, nothing on Urras that we Anarresti need! We left with empty hands, a hundred and seventy years ago, and we were right. We took nothing. Because there is nothing here but States and their weapons, the rich and their lies, and the poor and their misery. There is no way to act rightly, with a clear heart, on Urras. There is nothing you can do that profit does not enter into, and fear of loss, and the wish for power. You cannot say good morning without knowing which of you is ‘superior’ to the other, or trying to prove it. You cannot act like a brother to other people, you must manipulate them, or command them, or obey them, or trick them. You cannot touch another person, yet they will not leave you alone. There is no freedom. It is a box—Urras is a box, a package, with all the beautiful wrapping of blue sky and meadows and forests and great cities. And you open the box, and what is inside it? A black cellar full of dust, and a dead man. A man whose hand was shot off because he held it out to others.”

————

(Image from

https://www.david-lupton.com/folio-so...)

The intricacies of the social structure, politics and economics of Le Guin’s Anarres were so engrossing to me that I almost overlooked Shevek and his personal journey — until my friends’ comments made me slow down and reread parts of my reread and think of the human who is at the heart of the story. Shevek - so intelligent and so naive at the same time, who is not just content but seeks fulfillment and breaking the walls that separate and imprison us all.“But he felt more strongly the need that had brought him across the dry abyss from the other world, the need for communication, the wish to unbuild walls.”

As my reading group noted and I cannot unsee now, this is also a story of Shevek’s solitude and alienation. Shevek, our reluctant hero, does not quite belong in either society, an outsider in both worlds. He wants to break walls, but it seems that at all times there is a wall between him and the rest of whichever society he is a part of at the time. He’s always a rebel — but that’s right in his soul, as a true Odonian anarchist, a vehicle of change, of constant revolution, of anti-stagnation. But it’s difficult as we seems to have that hardwired primal need to belong, sooner or later.“He was alone, here, because he came from a self-exiled society. He had always been alone on his own world because he had exiled himself from his society. The Settlers had taken one step away. He had taken two. He stood by himself, because he had taken the metaphysical risk. And he had been fool enough to think that he might serve to bring together two worlds to which he did not belong.”

And that’s where his partner Takver comes in. Shevek and Takver’s partnership is at the heart of the story. It centers Shevek, grounds him, and gives him the ability to finally disrupt the status quo and step outside the wall, more than once. Strong, fulfilled and ethical people that are independent yet deliberately choose partnership. It’s solid, it’s tangible, it carries weight — and I really love it.

————

I don’t fully agree or disagree with Le Guin when it comes to this book’s complex ideas. She shows how an isolated and rooted in scarcity anarcho-communism can actually work - for better or for worse, as no utopias are infallible. Even the Sun has its spots, the saying goes. What’s important is that she makes you think about how things are and how they can be, the inherent allures and dangers in that, and the ideas can flourish and grow and slowly subvert what you take for granted. And for that I’m always thankful. And I come back again and again to this complex, intelligent, social and humanistic fiction of one of my favorite writers, and each time I feel that something little in me shifts and changes — and does not stagnate.“We have nothing but our freedom. We have nothing to give you but your own freedom. We have no law but the single principle of mutual aid between individuals. We have no government but the single principle of free association. We have no states, no nations, no presidents, no premiers, no chiefs, no generals, no bosses, no bankers, no landlords, no wages, no charity, no police, no soldiers, no wars. Nor do we have much else. We are sharers, not owners. We are not prosperous. None of us is rich. None of us is powerful. If it is Anarres you want, if it is the future you seek, then I tell you that you must come to it with empty hands. You must come to it alone, and naked, as the child comes into the world, into his future, without any past, without any property, wholly dependent on other people for his life. You cannot take what you have not given, and you must give yourself. You cannot buy the Revolution. You cannot make the Revolution. You can only be the Revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”

Unquestionable 5 stars. In my personal hierarchy of Le Guin books this is second only to

The Left Hand of Darkness.

This book may have aged a bit since it was written, but it never got stale.

————

Group read with Phil, carol, Jessica and Anna.

————

An amazing film “Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin” that has Le Guin talking about the worlds she has created is here:

https://vimeo.com/452853511

——————

Recommended by:

Mosca

——————

Also posted on

my blog.

-

Why America Is Full of Toxic Bullshit and Why Ambiguous Utopias Need to Check Themselves Before They Wreck Themselves Going Down the Same Fucked-Up Path

by Ursula K. Le Guin.

this excellent novel-cum-political treatise-cum-extended metaphor for the States lays its thesis out in parallel narratives. in the present day (far, far, far in the future), heroically thoughtful protagonist Shevek visits the thinly-veiled States of the nation A-Io on the planet Urras in order to both work on his Theory of Simultaneity and to pave the way for change on his homeworld. in chapters that alternate with this trip to Urras, we watch Shevek grow from boy to man on the anarcho-communist Anarres - the "Ambiguous Utopia" of the novel's subtitle. Urras and Anarres form a double-planet system within the Tau Ceti star system. The planets have a difficult relationship: 150 years prior, revolutionaries from Urras were given the mining planet of Anarres in order to halt their various revolutionary activities throughout the Urran nations. Upon establishment of their colony, Anarres cut off all but the most basic contact and trade with the despised "propertarians" of Urras.

The Dispossessed is a fiercely intelligent, passionate, intensely critical novel - yet it is also a gentle, warm and very carefully constructed novel as well. ideas do not burn off the page with their fiery rhetoric - everything is deliberately paced; concepts and actions and even characterization are parsed out slowly. its parallel narratives are perfectly executed, with different plot themes and character backgrounds brought up, expanded upon, and often reflecting upon each other. ideas are unspooled in multiple directions and serve to continually challenge reader preconceptions. overall this is not a novel that quickens the pulse (although there is some of that) but is instead a Novel of Ideas. if you are not in a contemplative mood, if you have no interest in systems of government or human potential or theoretical physics, then this is probably not the novel for you. it is a book for the patient reader - one who actually enjoys sitting back and thinking about things. Le Guin's prose does not jump up at you; nonetheless, she is a beautiful writer - equally skilled with the little details that make a scene real and and with making the Big Concepts understandable to dummies like myself. and Le Guin is a sophisticated writer. she seems constitutionally unable to write in black & white - everything is multi-leveled, nothing is all bad, nothing is perfect. humans are fallible; ideas are fallible. everything must change and yet the past is ever a living part of the present.

America as A-Io is where much of Le Guin's passion is displayed. however, the time spent in A-Io (roughly half the novel due to the alternating chapters) did not exactly challenge me. perhaps because i am already critical of the good ole U.S. of A., and have engaged in plenty of political shenanigans throughout my life, i wasn't reading anything new. i am the choir to whom the novel preached. still, i'm not sure i would say that this is Le Guin's fault. it's probably my fault, being an unpatriotic asshole who both loves and hates this crazy place, and who is in agreement regarding all the negative points - and the positive ones too (introduced fairly late in the novel by a Terran envoy). i am automatically sympathetic to all the points made about the ivory tower of education, hypocritical politicians, unncessary wars, the poisonous yet hidden class system, the demeaning of women, etc. still, despite my lack of enthusiasm about A-Io, this is also where some of the most wonderful writing occurs, and where some of the most mind-expanding concepts are described.

where the novel really shines is in the depiction of the Ambiguous Utopia, Anarres. everything is not peachy-keen on this arid, sadly animal and grass-free desert world. the ideals that created Anarres are indeed admirable; it was awesome to see my own (and countless others') anarcho-socialist jerkoff fantasies about how perfect it would be if we were all truly able to share, all able to chip in to help each other, if materialism was seen as an abomination, if we were able to give up on ridiculous hierarchical structures, etc, etc, et al enacted in a fairly realistic way and in a very positive light. but of course this is an "Ambiguous" Utopia, so Le Guin also shows how basic, power-craving, territorial human nature will always surface... how cooperative, communal living can also stamp down the individual, how it can make being different seem like a threat... how other-hatin' tribalism is ultimately toxic, no matter the tribe, no matter the utopia, no matter if the tribe is an entire nation - or world. Le Guin makes a utopia, then she nearly unmakes it by unmasking all of its issues and ugliness... but she does not denounce it. i loved that. Le Guin and Shevek still see the beauty in this culture, in a place that is anti-materialist, anti-capitalist; their goal is to explore how such a system can truly be maintained - in a way that is genuine and that respects the invididual, a society that is continuously revolutionary. and the true enemies of revolution are complacency and stasis.

a closing word and quick circle-back to the sophistication of Le Guin's writing: i loved how Shevek's Theory of Simultaneity was reflected within the book's structure and by the political and moral themes as well. an example:"But it's true, chronosophy does involve ethics. Because our sense of time involves our ability to separate cause and effect, means and end. The baby, agan, the animal, they don't see the difference between what they do now and what will happen because of it. They can't make a pulley, or promise. We can. Seeking the difference between now and not now, we can make the connection. And there morality enters in. Responsibility. To say that a good end will follow from a bad means is just like saying that if I pull a rope on this pulley it will lift the weight on that one. To break a promise is to deny the reality of the past; therefore it is to deny the hope of a real future. If time and reason are functions of each other, if we are creatures of time, then we had better know it, and try to make the best of it. To act responsibly."

-

When I started this novel I was a little worried because the prose seemed clunky and I was having a hard time settling into the novel. After a few pages that all changed, either I adjusted to her writing style or the writing smoothed out. If you experience this, hang in there, it is well worth sticking with this book.

I see some reviewers think of The Dispossessed as an anti-Ayn Rand book. I didn't come away with that impression at all. I thought LeGuin did an excellent job of showing the fallacies of capitalism and socialism. The reason that any system does not work is always because humans are all too human. Bureaucracy, consolidation of power, judgment, and inequality always start to wiggle their way into the social matrix regardless of the intent of the society.

Shevek, the main character, talking about his home planet Anarres, a socialist framework society."You see," he said, "what we're after is to remind ourselves that we didn't come to Anarres for safety, but for freedom. If we must all agree, all work together, we're no better than a machine. If an individual can't work in solidarity with his fellows, it's his duty to work alone. His duty and his right, We have been denying people that right. We've been saying, more and more often, you must work with the others, you must accept the rule of the majority. But any rule is tyranny. The duty of the individual is to accept no rule, to be the initiator of his own acts, to be responsible. Only if he does so will the society live, and change, and adapt, and survive. We are not subjects of a State founded upon law, but members of a society founded upon revolution. Revolution is our obligation: our hope of evolution."

Pretty heady stuff. Actually Ayn Rand could have wrote that statement. People find themselves on what seems to be polar opposites of politics, Republican, Democrat, Socialist, Capitalist, but in actuality all of them have more in common than they would ever admit. We all want the same things that is, in my opinion, the most freedom possible and still sustain a safe society. The difference is what system do we use to achieve those ends. Whatever system that the majority chooses to follow will eventually start to devolve into a facsimile of the original intent. Sometimes revolution, as abhorrent as it is, can be the only solution to wipe away the weight of centuries of rules and regulations that continue to build a box around the individual with each passing generation. I am not an anarchist, but I understand how people become an anarchist.

The book certainly made me think about my place in the universe and about the aspects of my culture that I accept as necessary truths that on further evaluations prove to be a product of our own brainwashing. Too many of the governing parts of our lives that we accept as necessary truths have never really been questioned and weighed in our own minds.

Why do so many of us work for other people now when a generation ago so many of us owned our own businesses? Walmart, though not the only culprit, has had a huge negative impact on communities destroying what was once vibrant downtown areas and forcing so many small businesses to close that it actually changed the identity of small towns. We were complicit in this destruction. We valued cheap goods and convenience over service and diversity. The capitalist swing currently is towards big corporations and I can only hope that eventually the very things we lost will eventually be the things we most want again.

So okay, I have to apologize for pontificating about subjects seemingly unrelated to The Dispossessed. This novel is about ideas and regardless of how shallow a dive you want to take on this novel you will find yourself thinking, invariably, about things you haven't given much thought to before. -

“My world, my Earth, is a ruin. A planet spoiled by the human species. We multiplied and gobbled and fought until there was nothing left, and then we died. We controlled neither appetite nor violence; we did not adapt. We destroyed ourselves. But we destroyed ourselves first. There are no forests left on my Earth.”

The Dispossessed is a phenomenal novel and there are many important aspects of it that warrant a thorough discussion; however, the above quote really stood out to me and will become the focus of my review.

It is important because it shows Le Guin’s preoccupation with ecological thought. And this is a constant theme through her work. The character in question has witnessed environmental collapse and understands exactly why it has happened; it has happened because there were no restrictions placed on appetite, indulgence, and violence. Resources became a commodity, and all the forests were destroyed. Humans did not adapt, learn or grow. They continued down their destructive path and it led to their demise. (I think she's trying to tell us something here, don't you?)

Le Guin establishes this by demonstrating that humanity is doomed to fail because of the divisions we have. She portrays two worlds diametrically opposed in their values. Urras is the crux of consumerist and destructive capitalism, and Anarres is an anarchist utopia in which no government reigns and every person is born equal. The former is driven by ideas of wealth and expansion, the latter by ideas of socialism. And although the alternative appears attractive to each counterpart, both have their own limitations because they cannot quite be reached in their pure state.

Shevek, the protagonist and a brilliant physicist, comes to terms with the unattainableness of true freedom due to the fickleness of human nature: it is an impossible goal. He, the only man to witness the limitations of both political ideologies, understands that neither are enough to save or to benefit humankind by themselves. The ideology of Annares and its emphasis on universal survival, through altruism, is certainly the most attractive to me (and to him), but its system is the easiest to exploit by the corrupt minded. This idea, for example:“We don’t count relatives much; we are all relatives, you see.”

This is a great concept because it extends the notion of family to every single person. Blood does not matter. Relation does not matter as we should look out for every single person regardless of our connection to them. This basic notion is innate and a moral principle for those born on Anarres. It is a simple requirement of society and it is there to ensure the survival of humanity. Everybody is here together, and they should work together. The ideology pushes universal altruism over individual aggrandisement, but if one deviates from this there are no repercussions. Trust is the key, but not everyone is trustworthy in life.

And this is where the story begins to become complex. The freedom discussed here pertains to the notion of individual expression and argument. Both planets believe that their system is best and will benefit human advancement if all embraced it. They close themselves off. They close their minds off. Shevek, as a scientist, wants his idea to benefit all. It’s not about political ideology: it’s about benefiting humans, all humans, as a whole and not taking sides.

The undercurrent of ecological concerns articulates this perfectly: we're all in this together and we must adapt, change and grow together so that we do not spoil our planet(s). We must not destroy our own humanity first because if we do then we will destroy our world, our forest.

Two years later, these ecological concepts would be expanded upon in the equally as phenomenal The Word for World is Forest (note the title and its link with the quote here.) And it's after reading these two works that I consider Ursula K. Le Guin not only one of my favourite novelists, but also one of the most important writers of the late twentieth century.

__________________________________

You can connect with me on social media via

My Linktree.

__________________________________ -

You question a lot of things when you read this book. Loyalty, freedom, desire to own, work, family concept .... I think the author has written a great book.

-

More than two months have passed since I've closed this book. While my traditional reviewing habit was one of immediately rushing to the closest laptop after reading the last line and sharing my excitement or the lack thereof in some hopefully original way, I felt a need to really let Le Guin's words sink fully into my mind and make them my own. (Actually, I've mostly just been very lazy in the reviewing department lately, but "letting words sink in" just sounds a little better.) But when it comes to making words my own, as this dear author evoked so well in this book, longing for possession is mostly futile, and so it is with ideas, impressions and most of all, inspiration. At least in my case good ideas tend to go and come as they please and if I'm lucky they can be grasped when there's something close at hand to write them down, just as the motivation and energy to write has chosen to quickly pass through my hands. Currently, the energy is there, but apart from some sparse notes that I now have to re-interpret myself, I only have a few central take-aways that I would like to share. This review can thus be considered as a barrel of some of the reflections I managed to retain before they too evaporated into untranslatable little figments of thought.

The first take-away is that this is one of my favorite books. It is engaging, it is exciting, it teaches and it entertains. Le Guin's prose is nothing short of wonderful. While the plot is not exactly extraordinary, it provides the perfect mobile in which to transport some important messages on life and civilization that this author has chosen to share.

The second take-away is that this is the best dissection of our society that I've read. I've read great books on the nature of human individuals on the one hand, and abstract philosophical meanderings on time and infinity, but never felt warm to the idea of reading about one of the levels that are in-between, namely society and civilisation. The reason why I never did is that there often seems so much more stuff wrong with society than right, so that it's hard to know where to begin complaining, and even harder to know where to stop complaining and inspire change. The building is showing so many signs of decay it's hard to dispel the idea to just throw it down and start all over.

Ursula Le Guin found a great starting spot in this book with which to make a nice filet out of our civilisation: the idea of possession. The need of people to "own" stands central in our way of life, and the illusion of ownership pervades much of our thinking and doing. I myself am not immune. To give just one example, I prefer to buy books rather than to go borrow them at libraries. To give another example: I just bought an apartment. Now it would be unfair to point the finger just at people here. Animals do it too, on a certain level. They want to own territory, but instead of throwing money around, they urinate all over the place or emit certain smells. For all the faults our society has, I'm glad we evolved away out of that particular habit, if only for the sake of still readable books.

Do I own these books because I gave money for them and they will soon by surrounded by MY walls? I guess so. Until a fire or a flood consumes them, until the hand of time consumes me. Yet, even though the banality of ownership during our short lives is inescapable, our ways of living are so much focused on exactly that futility it's no surprise so many people feel unhappy and wronged when they see their mission to that end either obstructed or sabotaged by those around them, or recognise their endeavors as futile once the mission seems largely fulfilled.

This is just a personal take-away of course, because if Ursuala Le Guin is doing one thing exceptionally well, it is the convincing way in which she gives each perspective on the matter a stage in this book. I can easily see the staunchest proponents op capitalism (and as someone who profits of that system's fruits it would be hypocritical and outright dishonest of me to claim that I dislike it myself) like this book as much as a dirty hippy or clean-shaven commie.

Possession isn't just about capitalism and material goods. It's more pervasive than that. Just think about how people refer to each other. "My" son. "My" girlfriend. "My" mother. Or how Jason Mraz chose to sing of his undying love by proclaiming "I'm yours". It's innocent most of the time, but when there's problems in relationships of any kind, quite often it is a question of a certain dominance, where one is under the other, where one is partly of the other. We like to own but we don't like to be owned. Except for Jason Mraz, that is.

While writing this review I was faced with another example of the futility of possession. I had made notes while reading this book that I intended to use to inspire this review. There are some interesting one-liners, some runaway thoughts, some links to real-life experiences. I would call them "my" notes. But what the two month span between writing them and reading them has shown is that even my thoughts are not entirely my own. Some lines I wrote down there are now perfectly incomprehensible to me. Others I can give an interpretation, but without the guarantee it will be the same as intended back in the day. How are these alien words still my notes?

"The Dispossessed" touches on many more themes than the one I evoked here, and Le Guin shows her genius on basically every page with throwaway wisdoms that pack a punch: on prisons, on the education system, on laws, on the press, on the world of art, the army, the list goes on. She can seem cold and pessimistic sometimes: "Life is a fight, and the strongest wins. All civilization does is hide the blood and cover up the hate with pretty words." or when she states that suffering, unlike love, is real because the former ALWAYS hits the mark. Despite this recurring pessimism, I found this book to be widely uplifting by looking through that veil of coldness and finding there the beauty of life, of all the things that transcend possession. Her criticism has an inherent warmth and is not above criticism itself. It's a criticism that has channeled my own apathy towards many of society's ways into something that seems more helpful: an understanding and even a renewed love. Yes, you read that right. I love society. There's nothing I'd rather live right next to. -

This discourse on dystopias won Hugo, Nebula, Locus, World Fantasy, and National Book awards, and almost every single one of my Goodreads friends that has read it has it tagged with a 4 or 5 star rating. So clearly, the problem here is with me, because I really hated this book -- and it isn't because this book is dated or aged poorly, because the Cold War era slant of this book plays perfectly to a modern audience considering the current state of Russian-U.S. relations.

I'm giving it two stars because I do appreciate the big ideas Le Guin brings up. The vision behind the "profiteering" cultures of Urras -- with subdivisions for the capitalists of A-Io (U.S.) and the authoritarian state of the Thu (Russia) -- and the anarchist outcast settlement of Anarres was a solid and interesting foundation for the book. But the weak characterizations, uninspiring writing, unnecessarily non-linear storytelling, lack of action, and disappointing ending all added up to a very difficult and unrewarding reading experience for me. To address those points specifically (mild spoilers may follow):

- There is only one character, Shevek, who is more than one-dimensional. The rest fill out the story as needed -- corrupt bureaucrat, radical friend, loving partner, etc. As for Shevek, for as brilliant as he is, he is naive to the point of incredulity. And I don't mean just after he leaves Anarres for A-Io. It takes him decades longer than his friends to see the corruption in his own anarchist world. He is willfully ignorant of what is going on around him for someone involved in something as deep as theoretical physics.

- The writing was clunky throughout the entire novel, and had no rhythm. There were tedious lists, long sections of discourse about the various imperfections in the various imperfect societies, and unnecessary word invention -- although I will grant calling the toilet a shittery is funny, if nothing else.

- Another aspect of the storytelling that did not agree with me was the alternating chapters, where one chapter would be a flashback to Anarres, and the next a current day chapter on Urras. I would have minded this less if anything interesting or noteworthy happened on Anarres -- what little did happen could have easily been worked into flashbacks in the current day chapters, which could have greatly shortened the novel, and likely, my enjoyment of it.

- There was one action scene in entire novel, and, if you include the aftermath, maybe ten pages are spent on it in total. There were also two other scenes that contained somewhat tense conflict. I don't need every book I read to be paced like

The Hunger Games, but I need more of an action-driven plot than this, especially if you expect me to sit through endless info dumps on your imaginary dystopias.

- The book ends right before another action scene -- or at least a scene with great potential for conflict -- that Le Guin either didn't know how to write her way out of, or didn't want to go out on a limb and make a stand for, which I see as a cop-out either way.

- The overall feeling I was left with after reading this book was that capitalism sucks, anarchism sucks in different ways, and the only hope forward lies in benevolent aliens. This could have been improved if the ending to the novel went one chapter further, however it turned out.

I could go on, but I believe my opinion is already more than clear. I will leave you with a quote from this book that sums up how I felt about reading it:He tried to read an elementary economics text; it bored him past endurance, it was like listening to somebody interminably recounting a long and stupid dream.

Goodreads friends, in all seriousness, tell me what I am missing that led you to rate this so highly. I feel like I am the only one seeing the Emperor's bare ass here. -

«Ωδή στο "όραμα" της ουτοπίας που ως "στόχος" ακυρώνεται ακαριαία».

Βαθύτατο ανάγνωσμα,προκλητικό,

δημιουργικό,με άπειρες προσλαμβάνουσες κατανόησης περί αυθεντικότητας,ατομικότητας,

διχοτόμησης,κυριαρχίας.

Το απόλυτο ανθρώπινο ιδεώδες και η ένταση της ανθρώπινης φύσης με την αναπόφευκτα διχοτομημένη δομή τους,προάγουν το βιβλίο σε μια αιώνια διανοητική πρόκληση.

Μπαίνουμε εξ αρχής σε ένα σύμπαν απόρριψης και αντιθέσεων. Σε μια καθολικότητα ώριμης σκέψης ανάμεσα στα όνειρα και την επίτευξη τους.

Απο τη μία οι ατέλειες της μοντέρνας κοινωνίας με κάθε δυνατή εξέλιξη,στην διακριτική ευχέρεια των πολιτών της καπιταλιστικής κοινωνίας. Οι ταξικές διάφορες. Το ατομικό συμφέρον,οι θυσίες των πάντων στο βωμό του κέρδους, οι άκαμπτοι ρόλοι των προνομιούχων και οι απίστευτες βιοποριστικές δυσκολίες των κατώτερων τάξεων.

Παράλληλα βέβαια,στην παρακμιακή καπιταλιστική κοινωνία συνυπάρχουν και γοητευτικές ομορφιές,πολυτέλειες που διευκολύνουν την απόλαυση της ζωής και πειστικές αρετές εντυπωσιακής πληρότητας μέσα απο τα υστερικά παράγωγα του άφθονου χρήματος.

Απο την άλλη, η εφευρεμένη κουλτούρα της αναρχικής κοινωνίας. Μια κοινωνία που αν λειτουργούσε πραγματικά θα επέφερε μια ηδονική πληρότητα στην ανθρώπινη ύπαρξη.

Εδώ ζούμε τη χαρά και την αλληλεγγύη της κοινής διαβίωσης,τα ουτοπικά δυνατά της αδελφοσύνης και της εθελοντικής συνεργασίας,τα κοινά αγαθά και οι παροχές που οδηγούν στην απόλυτη ελευθερία της ανθρώπινης βούλησης.

Την τόσο επικίνδυνη ελευθερία στο όνομα της εθελούσιας προσφοράς και της κοινοκτημοσύνης.

Παράλληλα όμως, όλο αυτό το σύστημα στηρίζεται στην πρακτική αναγκαιότητα και οδηγεί αναπόφευκτα σε μια πολιτική δύναμη που ακυρώνει κάθε ατομική δημιουργική ικανότητα και υπονομεύει το ατομικό νου.

Ακόμη κι ��ν πρόκειται για υποτίμηση ιδεών και σκέψεων που θα άλλαζαν τη δομική λειτουργεία του σύμπαντος.

Ο Σεβέκ (λατρεμένος) είναι ένας απίστευτα χαρισματικός επιστήμονας πάνω στη Φυσική.

Το έργο της ζωής του ειναι η ένωση των αρχών της Ακολουθίας και της ταυτότητας ( τι λέω η θεωρητική και δεν αυτομαστιγώνομαι;)

Πρόκειται,(αν κατάλαβα καλά, αφού αναφέρομαι στη φυσική και σιγοκλαίω) για μια γενική Θεωρητική •θεωρία• (πλεονασμός των θεωρητικών)

που ενώνει το χρόνο,ο οποίος κινείται πάντα προς τα εμπρός -με γραμμικό τρόπο, βλ. βέλος- και όλες τις ταυτόχρονα παροντικές στιγμές μέσα στις οποίες κινούμαστε.

Ένα έργο,το οποίο αν ολοκληρωθεί θα μπορούσε να φέρει σε άμεση επικοινωνία ολόκληρο το διαπλανητικό διάστημα.

Ο Σεβέκ βρίσκεται αντιμέτωπος με τα κακώς κείμενα των δυο κοινωνιών/ πολιτευμάτων/συστημάτων.

Ο κομμουνισμός και ο καπιταλισμός.

Είναι φυλακισμένος απο δική του επιλογή στην φυλακή της απληστίας και καταδικασμένος απο τους δικούς του συμπολίτες που τον πιέζουν σε μια "αναρχική" συμμόρφωση....

Ονειρεύεται ταξιδεύοντας σε άλλους πλανήτες να ολοκληρώσει τη Γενική Θεωρία του αποστολικά και επαναστατικά με σκοπό να εισάγει τις ελευθερίες της αναρχίας και των ιδανικών του στο υπόλοιπο σύμπαν.

Βρίσκεται όμως παγιδευμένος και εκδιωγμένος και απο τον πλούσιο καπιταλιστικό κόσμο και απο το κομμουνιστικό φεγγάρι της ανατολικής του πατρίδας.

Τελική απόφαση σε εκκρεμότητα ...

Αντικειμενική άποψη: ενεργοποιημένη.

Δεν είναι καθόλου εύκολο ανάγνωσμα.

Άλλωστε η "απόρριψη" δεν υπήρξε ποτέ εύκολη.

Καλή ανάγνωση!

Πολλούς ασπασμούς!!

ΥΣ. Ευχαριστίες σεμνές και γλυκές σε μια αλήτισσα ψυχή που με πίεσε-έπεισε να το διαβασω άμεσα.!! -

4, maybe 4.5 stars. This classic SF novel kept me glued to my chair the whole time I was reading it. Granted, I was on a cross-country airplane flight from Washington DC to Utah, but still!

It's very thought-provoking SF, set in the same universe as Le Guin's

The Left Hand of Darkness, but even more politically inclined. Almost 200 years earlier, a group of rebels left a highly capitalistic society on the planet Urras, to form their more utopian government on the moon Annares. Now a man named Shevek, a physicist from this voluntary communistic society, leaves his barren world, where life is difficult but - mostly - fair, to go to the neighboring planet to work with the physicists there. Life on Urras is much more pleasant and luxurious, but gradually Shevek comes to realize the dark underside of that capitalistic society. The question is, can he escape the bind he's gotten himself into?

The Dispossessed is one of the earlier examples of dual timeline storytelling in the SF genre, the chapters alternate between flashbacks of Shevek's life on his home world of Annares and his current experiences on Urras with the "propertarians" (heh). The Dispossessed thoughtfully examines the best and worst in these two political systems. Though Le Guin's choice of the better society is clear, it's laudable that she realistically handles how even good intentions can go awry because of human weaknesses like selfishness, fear and pride. Some might find this novel slow going, but if you're interested in contrasting political and social systems, I'd highly recommend it!

Even though this novel is 4th in the Hainish Cycle, it's actually first chronologically, for reasons that become apparent late in the novel (and are somewhat spoilerish, so I won't get into them here). :) -

“You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution.”

— Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed.

Ursula K. Le Guin's 'The Dispossessed' represents the high orbit of what SF can do. Science Fiction is best, most lasting, most literate, when it is using its conventional form(s) to explore not space but us. When the vehicle of SF is used to ask big questions that are easier bent with binary planets, with grand theories of time and space, etc., we are able to better understand both the limits and the horizons of our species.

The great SF writers (Asimov, Vonnegut, Heinlein, Dick, Bradbury, etc) have been able to explore political, economic, social, and cultural questions/possibilities using the future, time, and the wide-openness of space. Ursula K. Le Guin belongs firmly in the pantheon of great social SF writers. She will be read far into the future -- not because her writing reflects the future, but because it captures the now so perfectly. -

Mülksüzler sadece bilimkurgu türünün değil modern roman türünün de bir başyapıtı, şimdiden bir klasik. U. K. LeGuin anarkofeminist bir yazar, bu romanında hem anarşizmi hem de feminizmi sonuna kadar adeta kanın son damlasına kadar nakşetmiş.

Bu kitabı okuyacaklara bir önerim var. Mutlaka bir ön bilgilenme yaparak ve kitap sonundaki Bülent Somay’ın Sonsöz’ünü okuyarak başlayın kitabı okumaya. İnternette kitaba ilişkin çok doyurucu blog yazıları, bilgilendirici yorumlar var. Tıpkı Küçük Prens (A.S-Exupery) ve Hayvanlar çiftliği’nde (G. Orwell) olduğu gibi kim kimi veya neyi ifade ediyor, nerelere göndermeler var, anlatılan hikaye ile aslında hangi dönemler ve neler hedefleniyor gibi konularda bilgi sahibi olununca kitap çok daha keyifle okunuyor.

Kitabın ne konusunu ne de kahramanını anlatmam gerekmiyor. Ancak şunu belirtmek isterim ki bu kitap çok zengin politik, felsefik, sosyolojik hatta psikolojik bir kaynak kitap niteliğinde. LeGuin’in değinmediği konu yok neredeyse. Toplum yönetim sistemleri, iktisadi doktrinler, felsefik akımlar, din, evren, sanat, savaş, cinsellik, ekolojik sorunlar, eğitim, şiddet, bencillik, otorite, ego, kıskançlık, intihal, aile, üretim, muhbirlik, bürokrasi, aşk... gerisini yazmaya kalksam kitabı olduğu gibi kopyalamam gerek. Hatta göç sorunu ve mültecilik bile LeGuin’in kaleminden kurtulamamış.

Eleştirilecek yönü yok mu? Var tabii, örneğin, çok sayıda kurmaca “Kuram” ve “Hipotez” ismi kullanılması roman akışında karışıklık yaratıyor ve okumayı zorlaştırıyor, keza çocukluktaki hapishane deneyimini anlatırken LeGuin pek seviyeyi gözetmemiş. Buna karşın Oiei ailesi ile Shevek’in sohbeti en beğendiğim bölümlerden birisi oldu.

Özgürlük, sistemlilik, mülkiyet, eşitlik gibi kavramlar hiç lafı eğip bükmeden LeGuin’in kalemine dökülmüş. Nihayetinde insanlar için ideal bir sistemin olmadığı gerçeği ortaya çıkıyor. İnsana en büyük zarar ne kozmik olaylar ne doğal afetler ne de başka bir olumsuzlukla veriliyor, tek zarar verici yine insan.

Kitabı bir cümlede özetlemek gerekirse kitap içinden seçtiğim “Düşünceler baskı altına alarak yok edilemez. Onlar ancak dikkate alınmayarak yok edilebilir” cümlesini kullanırım. Çok beğendim ve kesinlikle bilimkurgu sevmeyenlere dahi öneririm.

Ön bilgi için bazı inceleme yazıları:

http://www.kayiprihtim.org/portal/inc...

http://www.bilimkurgukulubu.com/edebi...

http://www.arkitera.com/gorus/1158/mu... -

Thoughts on The Dispossessed

Of the various layers of content in The Dispossessed, the most obvious is the socio-political: capitalism vs. anarchistic-communism. The claim often made is that, even though her heart is with the latter, she nonetheless treats the two structures impartially. The claim or presumption is to be found in the reviews of fantasy/science fiction devotees, those with a particular interest in anarchism and, I suspect, also those who simply read it with an uncritical eye.

I don’t see that at all. Not surprisingly, given where her sympathies lie, le Guin has created the best possible picture of anarchistic communism and the worst of capitalism. In creating a capitalist society which has at its apex overwhelming plenty, perched on a base of workers whose existence is miserable beyond belief – going to hospital typically means being eaten by rats if one is poor – le Guin has created a capitalist society which is not only a morally reprehensible model but a very stupid one. Capitalism has known for a long time that one keeps those making up the base of support happy by giving them enough. That principle pertains throughout our society and there is no reason I can see to explain why le Guin’s capitalist model is different from that.

Contrast the anarchistic-communist model she proffers. By placing it in a poor, harsh geography, she creates the perfect setting for that model to succeed. Although superficially she is seen to consider the difficulties with the structure – when harsh becomes drought-induced-impossible, how does one decide who lives and who dies in this society – it is obvious that the real difficulties with the model arise when one considers physical ease and economic plenty. I can’t begin to see how any anarchistic-communist model then works, let alone one which has specifically been constructed on the presumption of struggle, survival, utility, function, purpose. The model she presents borrows much from the experience of the kibbutz movement in Israel. As it has failed, so too it is impossible to imagine her ideal society surviving.

This is the only le Guin I’ve read. Are all her books so stilted and contrived in style? There is a point at which dispassion by the author is hard to distinguish from a boredom that is infectious. I stopped reading The Seducer to take on The Dispossessed and this has made me appreciate how well-written the former is.

It has been argued that the dull tedious style is necessary to portray the poverty and utilitarianism of her utopian society. Sorry, I can’t see that for one moment. The woman hates writing, it is – unhappily for both her and her readers – a necessary medium to communicate her ideas. If she had commissions Ray Bradbury to turn her ideas into words, he would have made something beautiful without betraying the style she wishes to impose. But, then, Ray Bradbury loves writing.

Look, for example, at this list:

p.110 Coats, dresses, gowns, robes, trousers, breeches, shirts, blouses, hats, shoes, stockings, scarves, shawls, vests, capes, umbrellas, clothes to wear while sleeping, while swimming, while playing games, while at an afternoon party, while at an evening party, while at a party in the country, while travelling, while at the theatre, while riding horses, gardning, receiving guests, boating, dining, hunting – all different, all in hundreds of different cuts, styles, colours, textures, materials. Perfumes, clocks, lamps, statues, cosmetics, candles, pictures, cameras, games, vases, sofas, kettles, puzzles, pillows, dolls, colanders, hassocks, jewels, carpets, toothpicks, calendars, a baby’s teething rattle of platinum with a handle of rock crystal, an electrical machine to sharpen pencils, a wristwatch with diamond numerals, figurines and souvenirs and kickshaws and mementoes and gewgars and bric a brac, everything either useless to begin with or ornamented so as to disguise its use; acrues of luxuries, acres of excrement.

Sorry, but my average weekly shopping list is a more interesting read. Compare this list from The Seducer: