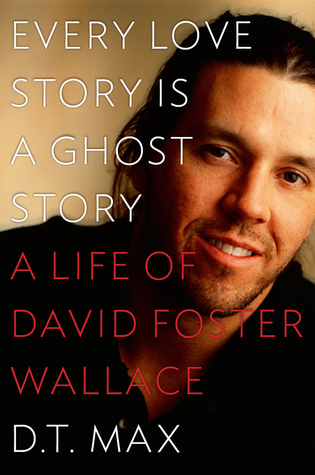

| Title | : | Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0670025925 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780670025923 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 356 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2012 |

| Awards | : | Goodreads Choice Award History & Biography (2012) |

David Foster Wallace was the leading literary light of his era, a man who not only captivated readers with his prose but also mesmerized them with his brilliant mind. In this, the first biography of the writer, D. T. Max sets out to chart Wallace’s tormented, anguished and often triumphant battle to succeed as a novelist as he fights off depression and addiction to emerge with his masterpiece, Infinite Jest.

Since his untimely death by suicide at the age of forty-six in 2008, Wallace has become more than the quintessential writer for his time—he has become a symbol of sincerity and honesty in an inauthentic age. In the end, as Max shows us, what is most interesting about Wallace is not just what he wrote but how he taught us all to live. Written with the cooperation of Wallace’s family and friends and with access to hundreds of his unpublished letters, manuscripts, and audio tapes, this portrait of an extraordinarily gifted writer is as fresh as news, as intimate as a love note, as painful as a goodbye.

Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace Reviews

-

Every Love Story is a Ghost Story is the book we did not want written or published in 2012, no more than we wanted “An Unfinished Novel” in 2011. No one should be happy that we have a biography of David Foster Wallace. But its publication was inevitable. And some of us are compelled to purchase it, read it, and object to its existence.

For those of us who have followed Wallace these past two decades, D.T. Max’s book is one part refresher of what we already know from Wallace’s books and interviews, essays and reviews about him and his works; and one part voyeuristic we-don’t-need-to-know prying into the private and personal, hashing through the life of a fucked up human being. It is an outline for a biography which will one day be written when a biography might serve the purpose of shedding light on the works of a master of his art. Today, the book is simply unnecessary, no matter the inevitability of its existence. Could a different biography have been written in 2012? I very much doubt it. And for those who would, may they apply their talents to reading, interpreting, and understanding Wallace’s works, his books, and not drudging through the life of “the real person behind the books.”

Most disturbing about Max’s biography is the audience implied by the text. No prior familiarity with Wallace’s books is assumed. This is perhaps most offensive. No one, having not experienced Wallace’s voice as expressed in his novels, stories, and essays, is entitled to read his biography. The book is written for those folks who might say something such as, “I’ve heard so much about this David Foster Wallace guy. I’ve not read any of his books, but I’ve heard he did a lot of drugs and really fucked up and some people really worship him so I’m going to read this biography to find out what all the fuss is about.” Again, the situation is inevitable, deplorable as it is.

As with any biography, Wallace is not its subject but its object. Anyone hoping to find “the real Dave,” thinking they might “get inside his head,” should know that the real Dave is in his own books; he is his own voice, his subjectivity expressed in his prose. What it’s like to be David Foster Wallace cannot be found in Max’s biography where Wallace is must needs reduced to an object of psycho-social study (inept, but even so). Again, this is necessarily so. But in 2012, we need Wallace’s voice and subjectivity; in 2062 we will welcome DFW, object of scholarship.

Love Story is not a literary biography. It is merely a biography and I cannot anticipate it functioning as an introduction to Wallace’s books. This is unfortunate because it is in the books the we encounter Saint Dave. The personal and voyeuristic information we possess about Wallace--that he was depressed, addicted, an asshole, a womanizer, got angry, was generally fucked up--will be from here to eternity used to object to our attributing sainthood to Dave. But sainthood is not a matter of moral athleticism; “saint” is not to be set over against “human being.” Rather, a saint is what emerges out of the experience of the despair of being human. A saint is one who refuses to succumb to the seduction of the merely human morass and endeavors to extract himself therefrom and return thereto. This is the stuff of which Wallace’s lifework consists. We insist upon retaining our notion of Saint Dave because his major effort was to make being human respectable again, and the drudging up of moral failures will not sully those efforts.

D.T. Max’s book is, then, to be read only by completists, those who have read everything Wallace has written and read everything available written about him. This book should clearly not be read by those for whom it was written, those unwashed masses and curiosity seekers, those grubbers and titillation seekers. In other words, the very people who haven’t, but must, read the words of Dave’s gospel.

__________

Alternative reading:

DT Max's long thing from

The New Yorker, 2009.

The Lipsky Roundtable from

New York Books, 2010. -

Yeah, this was just. Terrible. I don't even really have any smartassed thing left to say here after

the inchoate spew of status updates - it was just sort of depressing to read the last anemic thirty pages or so. It's a little heartbreaking how very terrible this was.

The NYorker article was great

(its Q&A wasn't: a possible warning?). His participation in

the Lipsky round table was great. I was really looking forward to this book. I was disappointed by

the excerpt but thought, maybe that was a result of condensation/editing?

No, it wasn't.

I wasn't expecting anything like Ellmann's Joyce or Middlebrook's Sexton. Maybe something a little more like

Turnbull's Fitzgerald. This just isn't even really a book - it's a mess. I d'know what happened, if it got edited to pieces or the hundred monkeys in the marketing department rewrote it or what. Stunningly bad. Probably the worst book I'll read all year - it's so shallow and disappointing and confused, even at a sentence-by-sentence level. Why did it have to be so awful?

Or, as

someone once wrote:

....know that an unshot discus's movement against the vast lapis lazuli dome of the open ocean's sky is sun-like -- i.e., orange and parabolic and right-to-left -- and that its disappearance into the sea is edge-first and splashless and sad. -

Non sapevo proprio niente di DFW.

Non sapevo che Foster fosse il cognome della madre, che amava, ma con la quale aveva un rapporto conflittuale ed emotivamente violento, al punto che per lunghi periodi della sua vita decise di non avere contatti con lei, nonostante fosse il suo punto di riferimento per tutto quello che riguardava la conoscenza della lingua Inglese.

(Dal padre, invece, professore di Filosofia, imparò l'amore per la Logica)

Non sapevo che David, sin dalla pubertà, soffrì non solo di depressione, ma anche di dipendenza nella più ampia accezione possibile - droghe, alcol, televisione (!) e sesso - cui fecero seguito ricoveri ed elettroshock, il che mi spiega, a posteriori, come abbia fatto a essere tanto capace nel descriverle in ogni minuziosa sfaccettatura, come potesse conoscere tanto bene tutte le sfumature di chi si sente diverso, troppo amato, rifiutato, messo su di un piedistallo come un statua (la Statua che a un certo punto ebbe paura di essere diventato agli occhi del mondo) e al tempo stesso non all'altezza, mai in grado di essere quello che egli stesso desiderava essere o che gli altri si aspettavano che fosse.

Non sapevo che l'insegnamento nei college, così importante per la sua carriera (anche di scrittore, anche postuma se si pensa al successo del discorso "Questa è l'acqua" rivolto a ai giovani laureati del Kenyon College nel 2005), riunisse in sé una dicotomia: insegnava perché aveva bisogno di lavorare per scrivere, quando insegnava (spesso) scriveva meglio di quando non lo faceva), non sopportava di dover insegnare per poter scrivere, ma quando non insegnava (spesso) aveva difficoltà a farlo e si augurava di poter tornare presto a insegnare.

Non sapevo che, per tutta la vita, frequentò e fu sponsor di gruppi di mutuo autoaiuto e di sostegno che, per tutta la vita, unitamente a pochi amici, alla famiglia e ad alcune delle donne della sua vita, furono la sua famiglia, i suoi amici, le sue donne.

Non sapevo che non solo intrattenne rapporti epistolari con Jonathan Franzen (la loro amicizia, e il loro essere amici rivali nel migliore dei modi possibili, soprattutto dopo il suicidio di DFW diventò di dominio pubblico), ma che per tutta la vita (ahimè troppo breve) scrisse moltissime lettere (che pagherei per vederle pubblicate e per poterle leggere - senza ombra di voyerismo alcuno, solo per l'aspetto letterario delle stesse), molte delle quali a scrittori, come Don DeLillo e Dave Eggers, con i quali mantenne i rapporti nel tempo.

Quello che temevo, era che questa biografia potesse rivelarsi morbosa, indiscreta, che potesse indugiare o scegliere di posare lo sguardo solo sull'aspetto più sensazionalista della vita dell'autore, mentre invece è vero il contrario: l'autore sceglie, progressivamente, di allontanarsi proprio da quello che tutti abbiamo saputo dai giornali il giorno dopo il suicidio di DFW, di mostrarci sempre più l'autore e sempre meno l'uomo.

Per quanto possibile, perché qui, più che mai, l'uomo e l'autore sono quasi la stessa persona, ma mentre l'autore possiamo ancora leggerlo, studiarlo, goderlo e rimpiangerlo, l'uomo ha invece portato via con sé il suo mistero e il perché del suo dolore e dei suoi fantasmi.

Tutto quello che non sapevo, quasi tutto, è in questa bella biografia scritta da D.T. Max, imperdibile per chi ami la scrittura di DFW, per chi lo ha letto e per chi vorrà, invece, leggerla affiancando la lettura delle sue opere e scoprirne un po' alla volta la loro genesi.

Troppe citazioni, troppi passaggi da riportare, troppo di tutto per riuscire a scegliere qualcosa che dia il senso di questa biografia.

Quindi solo due cose, e in entrambi i casi le parole sono le sue, di David Foster Wallace.

«Scegli con cura. Si è ciò che si ama. No?»

«Poteva fare la stessa cosa con il dolore destrorso: Resistere. Nessun singolo istante di quel dolore era insopportabile. Eccolo qua un secondo: lo aveva sopportato. Insopportabile era il pensiero di tutti gli istanti in fila, uno dietro l'altro, splendenti. E la proiezione della paura futura [...]. È troppo. Non riesce a Resistere. Ma niente ditutto questo è vero, ora. [...] Poteva accovacciarsi nello spazio tra due battiti del cuore e fare di ogni battito un muro e vivere là dentro. Non permettere alla sua testa di guardare sopra il muro. La cosa isopportabile è cosa ne penserebbe la sua testa. [...] Ma potrebbe scegliere di non ascoltarla.»

[Infinite Jest] -

All my adult reading life, I waited for a young contemporary writer to transport me to the prose-rich playgrounds of Nabokov and Pynchon. ADA and GRAVITY'S RAINBOW were my torches, but they were, arguably, emotionally sterile. When I read INFINITE JEST ten years ago, I knew I had finally found an author who, besides giving words an elastic, carbonated buoyancy, was a vigorously palpable storyteller, altogether tragic and heartbreaking.

I remember the exact moment when I heard that Wallace took his life (as I suspect did everyone who is reading this book, who read DFW before his death). It was like a brother or best friend had died. He was my rock star--my John Lennon, Peter Gabriel, and Bob Dylan all rolled up into literature. He wasn't yesterday's insurgent Kurt Cobain, he was today's voice--the insurrectionist of the insurrection, the anti-ironist and seeker of exigent summits.

D.T. Max evinces respect, compassion, and objectivity toward this now lionized author he has never met, in his biography assembled from the contributions of friends, family, lovers, AA comrades, colleagues, fellow writers, and epistolary confidants.

"Fiction is what it's like to be a fucking human being," Wallace said, and Max shows us the utter turbulence of this writer's life, a man who lived inveterately with the howling fantods (a phrase from his mother, the grammarian, used potently in INFINITE JEST).

David was a depressed, addicted, chaotic genius, a man who felt that he never lived up to his lofty ambitions as a writer or a person. He was both fascinated and repulsed by the TV culture and how media hijacks and propagandizes public and private minds--his constant themes in his essays, short stories, and of course, IJ.

As many know, he was hospitalized several times for breakdowns and overdoses, and struggled with pervasive suicidal ideation. Max does a virtuous job of giving the reader a candid view of the complex nature of DFW; the generously endowed writer was often a captious, violent, and tormented soul. He was also a passionate, outstanding teacher, and a patron to his companions in AA. Moreover, he was an enthusiastic dog lover, especially drawn to dogs with an abusive past.

The parts of the book that describe Wallace's years writing INFINITE JEST were not just revealing, but like a fourth wall nakedly exposed. Max captures the line between author and material with authenticity and revelation. It is almost surreal, as Max brought me back to the narrative of IJ while manifesting Wallace's actual art and pain of writing it. I don't want to spoil it for readers by dropping tidbits of information--reading about it is thrilling and gripping, the most page-turning part of the book.

The letters Wallace wrote to Franzen, DeLillo, Costello, and his editor, Michael Pietsch, at Little, Brown, and Company, (and many others), will prickle the skin of any DFW aficionado. He was self-conscious, and self-conscious about being self-conscious, and communicated that in his letters.

"I go through a loop in which I notice all the ways I am...self-centered and careerist and not true to standards and values that transcend my own petty interests...but then I countenance the fact here at least here I am worrying about it; so then I feel better about myself...but this soon becomes a vehicle for feeling superior to imagined Others...I think I'm very honest and candid, but I'm also proud of how honest and candid I am--so where does that put me."

This book is a valuable companion to David Lipsky's journalistic book, ALTHOUGH OF COURSE YOU END UP BECOMING YOURSELF, a biography of Lipsky's five days spent with Wallace on his IJ book tour. It is hard to compare them, as Lipsky's is an echo and interpretation of his actual time with DFW, and this book is compiled from sources outside of the biographer. Both have poignant insight into the ephemeral but perennial figure of Wallace.

I award four stars, rather than five, although the quality of writing and extensive research is first-rate (despite being almost devoid of familial testimony, and despite errors that I think are typesetting errors, not copy-editing, errors). It's personal. Something is missing, some essence that cannot be filled by a biographer, or hasn't yet-- the unnameable, soulful reflectiveness that I ache for. The closest way to that is through the Harry Ransom Center, which is fortunately only a few miles from my home, which houses David Foster Wallace's entire archive at hand. You can feel the pages while you read what he wrote, with just a slip of a glove separating you from his words.

There is something about Wallace fans--it is as if we are all in the same karass, isn't it? But Wallace wanted to relate to us on a cosmic scale, not like an exclusive club, yet he appeals to only select (not elite, but select) readers. If you become a lover of Wallace's work, you feel almost mystically connected to all other lovers of his oeuvre, and however fantastical a presumption, we also feel connected to Wallace, the person. It is apparent that D.T. Max understands this, and that he is bonded to Wallace, also. That is why (I think) he wrote this bio, about the ghost of David, who keeps on penetrating our literary dreams. -

"That was it exactly—irony was defeatist, timid, the telltale of a generation too afraid to say what it meant, and so in danger of forgetting it had anything to say."

-- D.T. Max, Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story

A good solid biography of David Foster Wallace. For a writer who was so hyped, celebrated and written about, it was a nearly impossible task to bring anything large or significant to the table with Wallace. D.T. Max did a good job. He didn't write a hagiography or sycophant's biography, but also avoided sinking into a loop of cheap theatrics that might have tempted another biographer. It wasn't a revolution as far as DFW was concerned or as far as biographies of writers either.

For me, it was like seeing a favorite movie star on a large HD television. You are suddenly aware of many flaws that either the author or his life had obscured or kept hidden before. You see things that seemed glossed over, or at least not obvious before. It doesn't alter one's perception of DFW too much, just zooms in and holds the historical camera still at the emotional cracks and the insecure little crevices. In Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, Max shows a DFW that is more insecure and conflicted than a superficial glance might portray. Wallace's self-conscious tendencies to enthusiastically bend the truth with friends, coworkers and family and to claim achievements (perfect SATs, etc) that were not his, but to second guess and be discomforted by those achievements that WERE his (Guggenheim Genius grant) was a valuable shading to the DFW myth. D.T. Max neither polished or defaced the statue of DFW life and achievements. He simply turned the statue and revealed another dimension to the man and his infinite genius and infinite sadness. -

A complicated chap, this DFW: capable of extreme selfishness and more than semi-noxious competitiveness, an explicitly excellent writer who posits concern for readers yet nevertheless once dropped from a great height "Mr. Squishy" upon our poor heads, an arch-grammarian thanks to his mom capable of making usage stuff look like calculations intended to trap infinity in a jar, maybe sort of a wonky weany despite his size and high-protein breakfast vomit, apparently helpless around the house beyond changing bulbs in his many lamps, a mama's boy who liked the ladies and the ganja when young, no apparent deep interest in fine art or music or food (beyond blondies and poptarts) or footwear (beyond untied workboots), psychopathically obsessive about Mary Carr in an unambiguously creepy way, worried about media's affect on American morality in what amounts to unattractive moralizing at this point maybe -- his intelligence and humor and perception and sentences are undisputed champs of the world but the overarching media-saturation sadness stuff and his obsessive insistence on sadness/suffering/darkness etc only seem to fight half the thematic battle (ie, what Milton called "light and darkness in perpetual round"). But I'm not here to judge the dude -- this is an impression of a biography that lays the foundation for better ones to come but which is very readable and steady and an excellent start. I admired how it mutes for the most part its judgments, how it presents the facts, the quotations, the timeline, the memories of friends etc and always lets us see the lies as much as the kindness. Typos and misused words (passify, skein) didn't overly distract me but I did find recaps of all work other than

Infinite Jest not so fun. Would've LOVED 25+ glossy insert pages of photos (at least the obligatory elementary school class portrait with young DFW, top left, eyes bright but mercurially averting direct contact with camera) and facsimiles of handwritten manuscript/journal pages and college transcripts and samples of his teaching syllabi! Generally, a serviceable bio studded with Franzen and DeLillo correspondence, with juicy bits about his total insanity for Mary Carr, plus details w/r/t his obsessive showering . . . Loved that he could write 22K words in a day. Loved that he brushed his teeth for 45 minutes every morning and night in college. Loved that the opening college interview freakout in IJ was based on real events at my (and Lenore Beadsman's) alma mater. Loved that he turned down inexpensive Iowa on financial grounds as though he couldn't get loans and teaching jobs -- or have his parents pay his way through his MFA. Mentions unrepentantly parochial books I'd heard he'd loved like (the unfinishably slow for me)

Catholics by Brian Moore and

The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis. After a point I couldn't put this down and it was a fine companion while cooped up sick as Superstorm Sandy devastated everything -- there's something asssociable about reading a long-awaited bio about the recently deceased DFW (a man known for his overwhelming intelligence and outsized novel) and the recent Frankenstorm that churned slowly up the coast. There's maybe something alternately devastating and underwhelming about both, too, depending on where you live (literally/figuratively). Ultimately, this more than sufficiently suggests what it felt like to be the FHB (fucking human being) known as DFW -- and it answered lingering WTFs w/r/t his life and superfucking heartbreaking death (surprised there wasn't a post-death chapter about reactions and a lot more about his final days than first appeared in the New Yorker article). Worth it if you've ever wondered about the guy's story, his high school history, his grades in the second semester of his sophomore year in college (spoiler: A+ across the board), how much action he got after IJ came out, how many students he slept with, etc, how many friends from recovery groups he helped out financially, etc, and have read the interviews and Lipsky thing and want to live in DFW World awhile more. It's a charismatic, virulent, thought-colonizing place but, again, thematically, I feel like it's maybe partially pathological and reliant on therapy/recovery-related simplicities restated in overeducated serpentine slipstreams of high/low language -- not all of it, just some of it, I'd say. What I mean is: what once was a literary marriage between author and reader built on unabashed love has changed its status to "it's complicated." Anyway, RIP DFW, although through IJ and your essays you'll live forever. After

Both Flesh and Not: Essays is published next week, let's hope for a bit of silence -- at least until the collected letters, emails, responses to student stories come out. -

Outline for review of D.T. Max's Every Love Story is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace

I. Introduction

A. Witty opening line. Grab everyone's attention.

B. Thesis statement: There is no reason to read this book.

II. Body ¶1: My thoughts on/knowledge of DFW pre-this book.

A. He was a tortured genius, suffering from major depression.

i) Among other personality maladies - crippling anxiety.

B. His brilliant novel Infinite Jest has influenced everything I've read since I read it six months ago.

III. Body ¶2: What I learned from Love Story.

A. Not much.

i) Love Story spends most of its pages reviewing the same concepts: DFW was a brilliant thinker and writer and theorist, but he had these demons inside of him that made it hard to get his brilliant ideas and writings out of his head and onto the page.

B. DFW was a womanizer.

i) It's hard to keep track of his girlfriends, much less his one-night stands.

ii) "Audience pussy".

C. Various details of the publishing business I did not need to know.

IV. Body ¶3: Disillusionment!

A. The wisdom present in DFW's novels is not present in his own life. He is no Dalai Lama.

i) Does this affect my reading of his novels?

B. The characters and events in his novels are very present in his own life.

i) Does finding out that there's a real person who closely resembles Don Gately make Don Gately less magical?

V. Body ¶4: The structure of this biography is frustrating.

A. The entire book assumes and points toward DFW's suicide.

i) This effectively takes the joy out of the author's life. The book's main focus seems not to be DFW's genius, but his foreshadowed death.

B. The book ends suddenly with DFW's suicide. There is no discussion of his legacy or the later publishing of his unfinished novel The Pale King, etc.

i) See (V.A.i) above.

VI. Body ¶5: But it's not all bad, really.

A. This makes me more excited to read The Pale King.

i) Where Infinite Jest investigates entertainment in the modern age, The Pale King investigates its inverse, boredom.

B. But that's mostly all the good stuff.

VII. Conclusion

A. Again, there's really no need to read this.

i) It will possibly disillusion you.

ii) It's unsatisfying content- and structure-wise.

END. -

An excerpt from one of DFW's first undergraduate stories entitled "The Sabrina Brothers in the Case of the Hung Hamster", a post-modern spoof on a Hardy Boys-type novel:

"Suddenly a sinister, twin-engined airplane came into view, sputtering and back-firing. It lost power and began spinning in toward the hill. It was heading right for the brothers!

Luckily at the last minute the plane ceased to exist.

'Crikey!' exclaimed Joe. 'It's a good thing we're characters in a highly implausible children's book or we'd be goners!"

I remember the first time that I was exposed to DFW was through a creative writing class in which we read “Incarnations of Burning Children” and it piqued my interest enough to search for his name on youtube. There I found his interview with Charlie Rose that I’ve, as of today, watched some seven times all the way through. I was struck, first of all, by his complete discomfort and what seemed to be, total aversion to social interaction. More importantly, I left the interview in complete awe of his intellect. I couldn’t believe that a person could be as intelligent, articulate, and well-spoken as he was. The combination of intelligence and emotional damage seems to be the entire focus this biography, and the focus that many take towards him. Although there much more to DFW than just that, no Bio could be a complete compendium of a person’s life, and when I’m honest with myself, these two traits are what has made me feel so close to him—the combination of deep genuine emotion and mind-bending intelligence. No author has made my “head throb heart-like” to quote DFW himself. It was these two things that I noticed when I first saw him through the screen of my computer and it was these two things toward which I felt an immediate pull. I vowed, at the time I first discovered his work, that I would some day, far off in my maturation as a reader, conquer the mammoth beast that Charlie Rose flipped through and referenced in their interview.

Flashforward nine months later, to when I gave the book a first go. I set out the goal of reading thirty pages a day, and with that rate, I figured I would finish the book in about a month. Oh, how naive I was then. I found the book to be not so much challenging and overly-difficult as it was time-consuming. The thirty pages a day challenge seemed modest (I’d surely read more than that on most days), but I soon realized it was too many pages. And each day I dreaded having to dive back into all those disparate plot-lines, hundreds of different characters, and page-dominating prose blocks. It was something of a mental workout routine to get through some of the sections. In desperation I reached out to online resources which provided full length descriptions of each character and plot line (I ended up spoiling some of the “reveals” later on in the novel in the process), but even this was not enough to keep me motivated. I soon gave up and moved on to other books with the promise that I’d return to the book some day.

Leap forward another six months, and I had found myself, once again, feeling the call of the Jest. A friend of mine had begun reading the book and singing its praises, mostly of the sections just beyond where I had left off (beyond the 200 page mark). I read chapter summaries of the sections that I had read in my first go-around, and started the book again from about page 140. With this new resolve I charged forward through doubt and occasional incomprehension. It took me about a month and half to get through it this time, but I actually finished it. The book had hit me like no other had—with the full-immersion experience, brought about by the intense concentration that I had to have in order to really get into its pulse. That, coupled with a new-found ability in my own reading, turned it into quite a powerful experience. Every time I sank into the book, I felt as if I had completely lost myself in another world, even if only to glean a small sense of what DFW was after with his fractured, broken story about addiction and entertainment. It also helped that I had recently found myself in the throws of a severely debilitating mental condition that I had thought was far behind me. I grew extremely attached to the book as it seemed to totally get everything that I was going through, had gone through and what I would go through. There’s something about the mere fact that another human being has experienced what you have that makes everything that you’ve gone through so much less terrifying and abstract; it made the whole thing feel so more human. And that’s what the book did for me, anyway.

I read Infinite Jest at the exact time I needed to and that was essential for making the experience what it was. And even though the timing of IJ was perfect—as far as who I was as a person and as a reader—I, of course, discovered DFW long after he had given up the ghost. There was no real reason for me to ever grieve over his loss—the knowledge of his death underlay my coming to be a fan of his work. But there was always a vague sense of disappointment and sadness that I hadn’t known about him while he was alive and thus, would never have the chance to meet him. But upon reading the final four pages of this biography, the reality of his suicide, what it must have meant for those close to him, what it must have meant for his fans, and what it meant to me as such a devotee to his work, hit me then and I became a huge mess, wailing into my shirt sleeve; it was pretty ugly.

I apologize that this isn’t really a review of the book itself, but I’m not very good at those kinds of reviews.

You can take the star I docked from the otherwise five-star rating and file it under the part of the review labeled “D.T. Max’s clunky writing/numerous typos/bad transitions and other things that I don’t really give a shit about”.

I hope I’ve written enough now. -

I didn't set out to analyze the varying levels of dirt to be found amidst Wallace's laundry, but here we are. This isn't a necessary book. This is a mix of tabloid sensationalism and outright fanboying that degrades the biography form, and if I might indulge in some fun misquoting of song lyrics for a moment: There's a whole lotta speculatin' goin' on...

2.5 stars. Wallace was no saint but this book exposes more than it might need to and therefore is primarily of interest to the voyeuristic and morbidly curious. His poor (and, uh, possibly criminal?) behavior is not ignored but neither is it ever condemned. See things like DFW's college aged quote-unquote courtship rituals, summed up neatly by page 147's too-casual observation: "Wallace did not hear subtle variations in no..." Awful things are mentioned but not pressed. It's a real missed opportunity, glossing over controversy in such fashion, but then again what is a biographer to do but simply report the facts?

Except DT Max doesn't just stick to the facts elsewhere and he never shies from showering praise on Wallace for the things he did well. So he's not an impartial juror. The book does help to draw together a unified view of Wallace's writing, linking major themes and concerns across his career. For that it's quite interesting to the heavily invested fan but practically useless for anyone not already drawn to Wallace. -

Workmanlike as predicted. Spits out the facts at warp speed nine. Main problem is it fails to render the aliveness of DFW or communicate the charisma of the man and his works. His life is depicted in terms of its struggles and suggests DFW inhabited a gloom-filled realm even in the moments when success and sex and productivity came his way, all of which were more abundant than the depressions and drug abuse. A bio of this superhuman writer should be grandiose and as abundant in ambition and scope as a DFW novel. Something in the Roger Lewis line. A bio like this is appropriate so soon after the author’s passing—some time needs to elapse before we have a 1,000pp exegesis of the man and his works, however . . . terribly lightweight. Two stars because the book gallops to a climax and doesn’t offer a whiff of insight into his last days. (And fails to even mention the publication of Consider the Lobster—heinous!). This purple cover also offends my delicate eyes.

-

DT Max has provided us with a chronological, journalistic, utilitarian, somewhat slight but ultimately satisfying biography-lens through which we can peer at a certain David Foster Wallace. The other lenses through which we can observe our refracted fellow are his own writings, his interviews, the many pieces and remembrances to emerge about the man himself since his death. Each one will give us a different Wallace; if Citizen Kane taught us nothing else it was that those speaking of others can never reveal but a fragment of a truth, so an untruth, or an approaching-truth. Ladies and gentlemen, let us be kind to Mr. Max- he saw to a rather unpleasant task, being the first to venture into the world of DFW biography. It had to be daunting, and he had to treat it with delicacy and distance, and it is obvious that was what he did. The trouble with writing about DFW is that the most interesting things about him were his work and his problems. Wallace even quipped to one of his college friends, around the time he was finishing Broom, that a future biographer would have to write, “Wallace sat in the library smoking a cigarette, and looked pensively at his paper as he attempted the next sentence- and who wants to read that?” It’s true. He didn’t travel. He didn’t hobnob with other famous folks (except through correspondence), he was private and troubled and anxious and depressed and found writing to be the only way through all that. So to write of the man himself is to write of his work and his problems. And DT Max is much more a journalist than literary critic. Much about the work itself is passed over in Wittgensteinian silence- so it had to be. I don’t fault Max for not being a Brian Boyd, whose biographical work on Nabokov comes packaged with mind-rattling analysis of the texts. Not many people are capable of telling a life as well as enlightening an oeuvre. So Max stuck to the former. Just the facts, ma'am. Or the facts as they are discernible through this certain focus. Let’s consider this the first tiptoes into the waters of DFW biography, a tentative step into a deep and strong-running current. Let’s use Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story as a reminder that Wallace himself embodied much of the potential as well as the turmoil of the millennial generation, that he attempted to express this in his writing, that he truly believed writing was a way out and through, and that we will be grappling with him and his body of work for a long time to come.

Not that Max was without his insights. I particularly like the idea he put forth that the real narrator of Infinite Jest is an immense, sympathetic intelligence that has our better interests in mind. But I had a strange experience reading this biography, which might be attributed to the fact that I read the majority of it over a two day span as I was simultaneously suffering from a mid-grade fever- I could not escape the feeling that Wallace was actually reanimated and forced to go through his tortures and achievements, his highs and lows, all over again. That he was forced to live again, to suffer through his struggles and fame again, to approach his fate again, simply because I had chosen to read this book! It was so odd and I couldn’t shake it and it made me feel guilty and sad. I suppose that is the risk of writing a very early biography of Wallace- those who knew him are living, those to whom his work was a salvation and a guidebook through dark times are still devoted to reading and passionately discussing him, his antagonizers and supporters and friends and enemies and lovers and family are all here to read what Max wrote, to experience again in the abstraction of words what was for them an actual breathing human. We’re still sorting out what he was and will be to us. He is still alive. So maybe it might have been better not to write this book just yet. But Max did a fine job of reminding us that what Wallace lived through is something we all share in varying degrees, the traumas and triumphs of this man are also of us and are exemplary of something we the living are all still dealing with. Putting that across seems like something of a success for this book.

While I was finishing Every Love Story Is A Ghost Story last night, by coincidence a friend of mine who I gave as a gift A Supposedly Fun Thing... emailed me to tell me he was finally getting around to reading it, and that “E Unibus Pluram” was affecting him greatly, and asked about Wallace in general but also asked whether there were other people writing about these issues as gracefully was Wallace did. As a closing to this “review” I’ll append part of what I wrote back to him:

“I am glad you are reading Wallace. I think his piece on television culture and fiction and perception is essential. It also gets to the heart of a lot of what he was intending to do with his own fiction, and I think it is a rather brilliant kind of cultural inventory of where things were at in the mid-90's, and it can be extrapolated beyond today. That the various levels of remove of actual experience increase as representation takes on more importance and presence. How substitutes for reality eventually supplant reality to degrees and depths from which we cannot return. How does one concerned with living a moral and valid life approach reality in such a fragmented, distorted world? This is the whole thrust behind Infinite Jest, but it is all over, super-saturating the essays in "A Supposedly Fun Thing..." and "Consider The Lobster". Why are Americans so obsessed with pleasure and entertainment, as if they are ends and results and not distractions along the way. Why do we feel entitled to vast pleasure? Why is so much advertising geared toward a product being the solution to anxieties? What is the source of the anxieties the products promise to alleviate? Why is our language so immersed in experiences we really have nothing to do with ("water-cooler talk" about TV shows and sports, things that happen at great distances, geographic and experiential, from ourselves), what is the self in a world where it is claimed that through media we can be "everywhere instantly", when in fact we are nowhere, always. What happens to our bodies when they are becoming ever more only filters for data or reproductions, imitations of images we see in media? This was his forte. His goal was to show ways to surpass this. What comes next? How do we recover attention and sincerity and control of our bodies in a world where all the tools for battling dispersion and inauthenticity have been subsumed by the forces of dispersion and inauthenticity?

Of course Wallace was not the only person thinking about this. Philosophers like Baudrillard, Derrida, Foucault, Barthes, Zizek, Deleuze and Guattari, are all about this. Wittgenstein’s language investigations are the key to everything. Writers like Pynchon, DeLillo, William T Vollmann, Franzen, many others, all deal with this in their fiction. It goes back through Marshal McLuhan and "the medium is the message" and on before that. What Wallace does so well is speak about it in the terms of the new millennium, he speaks the language of our epoch. He was that writer, the fabled one that wings down from some indefinite place and captures exactly the zeitgeist, the weltanschauung of what it is to be alive in our times. That's why he was such a big loss. The philosophers I mentioned speak in really high-level, dense, uninviting, academic prose. Wallace wrote how people speak, found a way to get these important, deep ideas across a broader spectrum. He was a link between the academic post-Wittgensteinian world of "world as word and representation" and us common mortals who didn't graduate double summa from Amherst. So yeah, read Wallace, essays and fiction. He is attempting to get to the core and reason of what is going on around us all the time.” -

Very mixed personal feelings--but, as the only Wallace biography out there it is definitely the trove of information expected (and more). Eye-opening to see the extent of Wallace's mental demons; saddening to see the effects of those troubles manifested and exacerbated by substance abuse. Still astounding to see how such troubled/tortured/unsavory people can produce such sublime art. The prose is clunky, sure, but that wasn't a goal of a book like this so I disregard the style and consider the data. The research and effort here are extraordinary.

-

This is a serviceable biography of David Foster Wallace. It's not one of the best-written books I've ever read, and it will surely be hated by those who feel DFW should be spoken of only in tones of hushed reverence, but it got the job done. I'll share some pertinent facts from Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story in my upcoming review of Infinite Jest.

-

This biography, useful as it is in providing some needed context, feels flimsy.

The most obvious missing piece in this bio is an exploration of David Wallace's relationship to his mother. It is quite clear even from Max's work that this relationship was central both to who David Wallace was and to the stylistic and thematic choices in his work. The difficulty of such an endeavor is clear. In unveiling whatever that relationship might have been like, Max risked offending Wallace's family, a risk that can derail a biography. The qualms of writers of biographical material, both tactical and borne out of common courtesy and compassion, are well exemplified in the first piece that actually touched on the matter of Wallace's relationship with his mother. In Maria Bustillo's

Inside David Foster Wallace's Private Self-Help Library, comment after comment on the self-help books he owned point to the crippling influence of his mother on Wallace's life. After this article was published, revealing something that reader's might have been gleaning from pieces like Suicide as a sort of present, Present Tense... and character's such as Avril Incandenza, a total of 21 out 320 books from the library of DFW on display at the Harry Ramson Center in Austin were removed from public access by Wallace's Estate. There is no question that family members should be spared the grief of seeing their intrafamilial relationships dissected in public in a biography. Also, arguably, no biography of David Foster Wallace can be complete without an extensive exploration of this relationship. This conundrum probably means that we will have to wait for a definitive biography of Wallace for a few years.

Further, there is extensive research done up until after the publishing of Infinite Jest in 1996, at which point Max makes a mad dash for the finish line as if the main objective of the bio had already been accomplished. It takes Max until page 220 to get to the publication of IJ and he then proceeds to wrap up the next 6 books, Wallace's final crisis and all material and analysis of Pale King in 80 pages. This approach left me with the feeling that Max unspoken conclusion for the biography was that Wallace is a failed writer, that published an astounding but essentially unfollowable book in IJ. This would be a massive underestimation of Wallace's work. It is also, however, possible that Max simply ran out of time. This was widely expected book and there must have been a lot of pressure to put it out fast. One would assume that if heavy research was put in at the early stages, it would have had to be sparse at the end with the deadline approaching.

Max's style provides evidence to support the rush theory. There are, for example, sentences that must originate in transfer from subject to biographer and that patient editing might have weeded out, such as in the inadvertently funny: "He knew that he had to write for himself and not think about the reader, but that was easier to enunciate than to enact." One is reminded of Wallace's video about "puffed up words", as well as his penchant for renovating clichés with smart word play; in this case, however, "easier to enunciate than to enact" is not an improvement on the equally lame cliché "easier said than done". The book is not badly written, but there are a few of these little surprises lying around in it.

The biography also fails to transmit what Wallace aptly called his "psychic pain". In Max's bio Wallace will be feeling depressed in one sentence and then hospitalized in the next and out of the hospital by the next paragraph. There is a feeling that Max felt that dwelling on unsavory topics such as what it actually feels to be severely, clinically depressed was somehow offensive to his subject, or that his journalistic principles kept him from approaching the more subjective aspects of "how it felt" for Wallace. This, of course, can all be found on Wallace's work, but one would think it necessary in a book that is supposed to provide context for his own life decisions.

Is this DFW first bio worthy of your attention, then? Yes, despite its shortcomings. It provides much needed information and context. There are no incredible insights from Max himself, it feels rushed and skips important topics, but it is in all a worthwhile read. -

Se siete dei fanatici di DFW buttatevi a capofitto su questo libro. E’ scritto apposta per voi.

Se come me volete solo sapere qualcosa in più su un tizio con bandana, stivali Timberland slacciati e camicia a quadri probabilmente ci troverete dentro fin troppe informazioni, date, note. Ma vale ugualmente la pena.

Ci sono molte cose: scoprire come sono nati i libri, l’influenza di Pynchon. I periodi di malessere, smarrimento senso di colpa. I ricoveri nei reparti psichiatrici e i riconoscimenti accademici. Tv, alcol, droghe, solitudine. L’amicizia con Franzen e le lettere con Delillo. I tour di presentazione dei libri e l’insegnamento. Infinite Jest che diventa un cult. La fine.

Gran lavoro di ricerca e ricostruzione dei fatti. Consigliato. [75/100] -

Best parts of the book by far are the flurries of DFW's quotes copied wholesale, albeit they still suffer from DT Max's flimsy attempts to give context. The book wades only in shallow waters and rickety theories, with no cutting insights whatsoever. Why did DT Max even write this, then?

Another reviewer already said very succinctly my overall impression of this book: it reads like a long wikipedia article. Personally, I'm a huge wiki fan. I wiki all sorts of shit. I glean biographies of my favorite famous people on wiki. The main reason wikipedia entries work so well for my procrastinatory casual research purposes is that wikis are non-emotive—you can read the blurbs of factoids any time of the day or night and you are never changed for the better or worse, just heavier with whatever information you came for, meh, and life goes on.

Sounds like DFW's biggest nightmare? But then again, I'm just projecting. Did DT Max take DFW's later fascination with boredom (and its perceived zen-like benefits) as an endorsement of it?

Read the book for more than 30 pages in one sitting and you can feel the effects of the marked lack of direction. A gander at the chapter titles tells you nothing...which goes back to the directionlessness of this whole thing. Don't get me wrong, I bought the book the day it came out, full sticker price, read it diligently and delighted at the bits of facts and DFW's witticisms, and, I suspect like many others, I bought the book because I couldn't not buy it. There were things about DFW's life that I wanted to know, felt I had to know. But I'm not about to conflate my love for DFW with my feelings about his biography—the weakest link here is DT Max.

His formula seems to be: throw in what I know about what DFW did and then construct concepts around them, however vague. The result is a lot of mundane info (some of which I did love), but each mundane tidbit follows the pattern of trailing...off...into...a dead end, a great void unconnected with anything, then another tidbit surfaces out of nowhere, before trailing off again...then another...and another...

Somewhere in the middle of the book it is intimated that DFW fell out with his mother. No further exposition is given, which is incredibly unsatisfying, since the book opens with plenty details about how close the two once were.

Finally, the way the book ends shocked my socks off. Not that I was expecting a final bow to tie it all up, but this hurricane that terrorized the final 5 pages of the book? In a few pages DFW goes abruptly from a content/stabilized person struggling with his novel (as he's perpetually doing all his life) to someone who goes off his regular medication, attempts suicide, vows to never do it again, returns to shock therapy, and finally ends his life? It made me cry.

I know DT Max mentioned before that he vowed not to write a "sad" book, but the paltriness of this text is like a meta-sad, sadder than sad because your original desire to not be sad tried too hard to be not-sad.

:( -

I'd like to write a very long and thoughtful review of this but honestly when would I have time. I have nine minutes till I need to get dressed and head to Penn so wanna hear it here it go.

1. This book is not perfect. If that surprises you you are a moron. Some of the reviews I've glanced at so far have been written by morons. If you expected to pick this up and by its virtues have the absence of his death filled, to have the absence of his life in your life (because you didn't know him, he was just some guy somewhere else in the world, he didn't know you) filled, you are a moron. Go somewhere else. I have wounds to lick and I will be busy for some time.

2. D.T. Max never met Wallace. This is just a biography it is not a memoir.

3. I didn't think I was going to read this, I don't generally care for biographies and in addition I have an extremely raw hole in me that is DFW-shaped because he is in some senses THE holy blissful martyr (non-canonical) of the very stuff that permits for my very BEING in the world, he is the sacrificed lamb for some of us and for some of us we would have preferred our sons our wombs our hearts our bodies whatthefuckever to be engulfed in flame to be sunk in tar rather than bear this sacrifice, rather than string this lamb, I mean it is just a very very very very essential and fundamental and NECESSARY place, this little small tattered clothbound space some of us are carrying around, poring over it in bathroom stalls between cigarettes shivering and drenched and all of it pouring, hot waves of it pouring, fainting on the couch beneath the afghan, returning to its little words and breaths and bread, waiting here, waiting to finish it waiting for it to consume us, waiting

But then a friend, whose opinion I at least generally kind of agree with, referred to him, in the worst place on the internet, as a "misogynist asshole" and a hot fury piss-white and boundless burned through me and I had to duck back under the cloak of text, you know how you have to duck back under the cloak of text sometimes when your shit gets all knocked around, and so.

And but so.

And but so this seemed a safe little place to go. And it was. His life was silly and perfect and stupid and clumsy and an accident and a striving and here is the thing: If anyone anywhere ever tried harder to better the self that he was, I don't know. I don't even know what that effort would look like. I don't even know that I'd want to know it existed, that effort. Because the failure of this one is enough every time I think of it to make me question the sense of the project in general, which is as close I think I safely can come without throwing all the towels in. All the towels covering all your chairs, all the towels drenched in all your sweat, a thousand years of solitude, you try you tried you tried so fucking hard. -

I am a huge fan of David Foster Wallace -- the person who tried, so hard. His books were not necessarily my favorites, but something about him pulled at me. I've read everything I can find about him, every interview, every article, including the New Yorker article by D. T. Max. I bought this book as soon as I heard about it, pre-ordered it, and was thrilled the morning it was automatically delivered to my kindle. Couldn't wait.

And this was the most shallow, trivial biography I could imagine. I gave it three stars because it was about David Foster Wallace, who means a lot to me. But the book itself? I'd give it one star. I have to say that I’m extremely disappointed with the biography; it’s really just a book-length Wikipedia article. It goes into arbitrary and uninteresting detail (like what movie and which restaurant DFW went to on a date with a woman who wasn’t an important figure, just someone he dated, or that Franzen recalled that Wallace used a lot of wiper fluid on a car trip), but then glosses very quickly over what are clearly important events. There is little to no psychological interpretation, and in fact it seems like Max simply did not want to go there. I hope Blake Bailey (author of the fantastic biography of John Cheever, and another of Richard Yates) decides to write about Wallace. Now that would be a book to buy in hardback. In the acknowledgements, he says that all the important people in Wallace's life were open and generous with him, but the book surely doesn't read that way.

At every turn, he takes the gloss. At every turn, he gives the shallowest description of what happens. It's like he refuses to step beyond the "then this happened, then that happened" to offer a substantive, integrative comment on what happened. In fact, I knew more about Wallace already than I learned in this book. This happened, then that happened, then he hung himself, then that's it. SHALLOW. Like Wallace's death, this book left me feeling cheated. I just wanted more of him.

It's the only bio there is right now so I'll take it, but it's a pretty pitiful biography. -

Boeiende, prettig geschreven biografie, die ik met plezier heb gelezen, maar die naar mijn gevoel te veel ruimte laat voor verdere speculatie over de 'mythe' DFW. Ik bedoel hier mee dat de biograaf zijn onderwerp te veel karikaturiseert, wellicht en hopelijk tegen wil en dank. Liever had ik de man achter de mythe leren kennen, hoewel het de vraag is of dat hoe dan ook mogelijk is bij een dergelijk complex onderwerp en wel binnen het bestek van wat uiteindelijk een vrij korte levensbeschrijving is. Zo krijgt de lezer tot vervelens nogal pueriele beschrijvingen van DFW's look of het aanzicht van zijn kamer voorgeschoteld. De analyses die Max biedt van de werken zijn niet altijd even raak of interessant. Bovendien staan in deze bio niet alleen een aantal onbegrijpelijke inconsequenties (nadruk op moeilijke relatie met ouders en vooral moeder maar zonder dit verder uit te diepen; promiscuïteit van DFW: dan weer wel dan weer niet; vriendinnen die uit het niets opduiken en zelfs geen naam krijgen; stoppen met nemen van Nardil dat tot suïcide leidt, etc.) maar ook fouten (onder meer beweren dat Avril in IJ met de broer van James een koppel vormt, terwijl iedereen weet dat Tavis haar adoptie/halfbroer is). De vele citaten uit brieven aan Franzen, DeLillo en Costello zijn heerlijk, alsook enkele anekdotes en levendige beschrijvingen van publieke optredens van DFW. Een boek voor de fans.

-

William Wallace was 7ft tall and shot fireballs out his ass.

Thanks to D. T. Max, David Foster Wallace no longer does this.

Whether or not Wallace agreed this book was necessary for him to stop doing shooting fireballs out his ass, it was for me. Intent delivered.

I’ve been recommending the film Another Earth to many people. I can’t remember much about it now, to be honest. But I remember this other Earth in the background of shots where the protagonist considers her regrets: her problems carry the weight of the world. “Sometimes I can hear my bones straining under the weight of all the lives I'm not living.” Or when I travelled to the other end of the Earth to visit some friends who still could not stop acting like their needs were not fully met, our love remaining unproved, yet there was no further distance that exists that we could have travelled to see them.

We do carry problems in our head that, to us, feel as if they carry an infinite mass. Problems of the imagination are the biggest and most severe that exist because they can invisibly carry infinite properties and magnitudes. A book with the finite density and finite mass of Infinite Jest did not cure Wallace’s continual (as in on-and-off always) feelings of inadequacy, of not mattering. This to me is a very reassuring lesson because it is a reminder that the jury is out on every one of us while we’re still around: age, background, fame, wealth, success- no one is free from this truth. And while I may profess to the infinite neediness of friends of mine or a character in a film, it’s quite telling of my own neediness that I couldn’t allow Wallace his freak of genius and had to reveal him as human to myself. But that I did, and feel all the better for it.

It was quite funny that despite some of Wallace’s hemming and hawing captured in his letters to surrogate writer-dad Don DeLillo, his books just seemed to appear in the narrative. “Wallace was thinking about rehab so he sent a 750,000 word manuscript to Little, Brown.” (not a real example lol.) It doesn’t quite capture the tenacity and persistence required to write something of that length that remains readable and does not significantly repeat words, themes, speech, story arcs and balances the chat accordingly across all 100+ characters? And yet the tenacity and persistence I refer to were far from Wallace’s alone, as his friends and lovers- each as enchanted by his company as infuriated by it- bore much of the brunt of his flailings.

I have to deduct a star for the occasionally strong assertions when it came to Wallace’s work, for example that The Depressed Person was “revenge fiction” against Elizabeth Wurtzel for not sleeping with him, when Max himself later points out that Wallace told his wife Karen Green it was about him. This no more clears up the matter, as Wallace did try to create obscurity when it came to the personalization of his writing, but The Depressed Person remains nameless and essentially genderless for a reason.

And also because I know that with this new context, I will read Infinite Jest for a third time- not that two readings cleared that fucker up, to be sure.

This was not in fact my idea but the idea of a G GR friend of mine, but I’d like to open the floor: through his obsessions, bouts of rage and confusion at his partners, penchant for cerebral and conceptual analysis of problems of the heart: was Wallace autistic?

(Holiday read I am making time to review despite being ball-deep in editing :D) -

How can you write a true biography, a biography that really captures a human's whole life, or even just "the important" parts of it, and still moves smoothly from one important event to another?

Rhetorical question. I don't have the answer. D.T. Max certainly doesn't have the answer either. DFW once wrote about how impossible it would be to even accurately capture the infinite stimuli of a fleeting moment, so I don't envy the charge that a biographer takes on.

Here are a few things I really didn't like about this particular biography. Many of the transitions (or lack there of) between sentences, between paragraphs, and between "important" parts of the subject's life are just awful (due to their afore-parenthetically-mentioned non-existence). Next, Max's use of endnotes. There were many pieces of interesting/personal DFW details for which I wanted to know Max's source. Instead of clearly (and in my opinion properly) documenting them by using endnotes, Max devotes his endnotes to little "asides," making them seem like space to dump stuff he couldn't fit into the body of the book. (Similar to how he describes DFW's use of endnotes in IJ.) Since this is a biography, I feel that it needs to make a point of clearly documenting its sources--see Charles Shields's

Vonnegut Biography. Unfortunately, dumping narrative tidbits in the back doesn't stop Max from also peppering in the most random and unnecessary facts every now and again in the biography proper. Finally, there are many parts of DFW's life about which I would have liked more detail, parts brought up by Max but not sufficiently delved into. Perhaps he could have devoted more space to adding depth here by limiting the amount of space given to summaries of DFW's work.

Here are a few things I liked about this particular biography. It was about David Foster Wallace, a writer and person I admire. It gave me a fair enough overview of Wallace's life. The writing did move along well-enough and there was a spare great sentence here or there. Even though I knew how it would end, I couldn't arrest a few tears on the last page. No expert on Wallace, I oddly can't come away from this 300 pages saying I've learned a great deal of new information about his life; nevertheless, I enjoyed reading about his life.

Here are my excuses for not supporting the above claims with textual evidence. It's late. I'm tired. I'm lending the book to someone tomorrow.

Oh, and I've got to throw this in here. I lied, the opening isn't exactly a rhetorical question. The correct answer is "Ask Brian Boyd." (I can't review a biography without mentioning the gold standard.) -

DT Max breezes through the childhood, does a thorough job on the rise and fall and rise of the Broom to Infinite Jest stretch, and gets a little lost during a whirlwind tour of the final decade. Though it wasn't Max's intention—this bio is most def sympathetic toward its subject—he manages to make DFW rather insufferable. I blame this on an inability to find a foothold in the 21st-century leg of the story and his over-reliance on letters (the "biographer's oxygen" he calls them) in which Wallace frets endlessly over his writer's block and where he fits into the cosmos of American literature. The careerism becomes positively stifling. By the time I was done, I fled to

A Month in the Country just to remind myself what a self-effacing, simply told story looked like. One suspects there was a nobler artist, not to mention a somewhat less single-minded guy, than what comes through in the final chapters.

But the hot streak is very well done. You really feel the gears grinding as Wallace creates his masterpiece. That peculiar Amhurst-Tucson-Cambridge-Bloomington-Pamona trajectory (and the depression-wellness-relapse trajectory that ran alongside it) is vividly evoked, and there are beautiful distillations of Wallace's thoughts and predicament along the way. Max writes of "the mistaken American belief that pleasure can do anything other than stoke the need for more pleasure," notes how the grunge sensibility "flew in the face of [DFW's] recovery theology," and that Wallace "knew only way one way to seduce: to overwhelm." He also makes it clear what a bitch of confrontation the unfinished Pale King was for Wallace. And his portrait of a charmingly bourgeois genius who was a regular Joe in most regards and whose imagination torturously stopped revealing itself at one point rings true. Tragically, the post-Jest years would be largely a dead end. He came to feel time was passing him by.

The book's a quick 300 pages and, for better or worse, reads something like an extended New Yorker article. No doubt a fuller biography will come out eventually. And a Selected Letters, just you watch.

(I wish my old friend George Garrett was still around so I could ask him about how he hid Wallace's socks and shoes one night in Yaddo when he [Wallace] was having it off with Alice Turner in one of the bedrooms. George held out on us with that story.) -

Przyznaję, że zaczęłam czytać Wallace’a dopiero w tym roku, ale o nim samym i o jego twórczości słyszałam od lat i od lat obiecywałam sobie, że po niego sięgnę bo jego książki (i on sam) wydawały mi się być w moim stylu (Pynchon vibe). I nie pomyliłam się, ale po przeczytaniu jego biografii lubię go trochę mniej, i choć bezsprzecznie był postacią genialną to dla mnie przede wszystkim jako człowiek był postacią tragiczną.

Biografię zaczęłam czytać będąc w trakcie jego największego dzieła „Niewyczerpany żart”, który dopiero co po raz pierwszy ukazał się po polsku. I wbrew pozorom ten ruch był bardzo trafny, bo powieść zajmuje sporo miejsca w historii o DFW, dzieki czemu mam wrażenie wyciągnę z NŻ jeszcze więcej (tak, nadal jestem w trakcie bo to tomiszcze ma ponad 1000 stron). I nie, nie jestem spoilerową maniaczką, zresztą to nie jest tego typu książka, którą w ogóle można zaspoilerować.

Co do samej historii, któtkiego bo 46-letniego życia kultowego pisarza, to tak jak wspomniałam wyżej była ona tragiczna. Zmagał się z niedopasowaniem, uzależnieniem i ciężką depresją. W mojej teorii świat po prostu nie był na DFW gotowy, on wszystkich znacznie wyprzedzał czy to w bystrości i geniuszu czy we wrażliwości. Kochał psy, fascynował rapem i pornografią, zakochiwał się na zabój i potrafił się pobić z sąsiadem o książkę. A książki czytał stosami i to od dziecka.

Zdradzać więcej nie będę, ale autor D.T.Max wykonał kawał roboty, i w kwestii doszukiwania informacji o DFW, ale i w kwestii językowej bo czyta się to znakomicie (oczywiście również dzięki tłumaczeniu Jolanty Kozak).

Polecam bardzo, nawet jeśli nie znacie Wallace’a -

This is a good source of info about David Foster Wallace, if you're into that sort of thing (and I am). But it's not a very good book.

Wallace was a confusing figure, full of apparent contradictions. You might expect a Wallace biography to open with a set of questions, with some description of how it intends to investigate Wallace's life and what it hopes to get out of that investigation. Instead, Max's book begins with the strangely clunky sentence

Every story has a beginning and this is David Wallace's.

That sentence exemplifies the book. It's framed not as an investigation but as a story, told in entirely chronological fashion from Wallace's birth on page 1 to his death on page 301. In addition to providing facts, Max gives us his own interpretations of Wallace's work and ideas, but those interpretations are woven into the narrative and stated in declarative fashion, as though they were just as factual as the names-and-dates-and-quotes material that surrounds them. Max never acknowledges his own interpretive leaps and inferences; he simply writes that "Wallace thought this" and "Wallace thought that" rather than explaining how he reconstructed Wallace's mental state from interviews and letters, and what alternative reconstructions might be defensible. (Whenever Max does offer an alternative explanation, it's always confined to an endnote, as if Max thinks that including it in the main text would break the narrative illusion.)

In short, it's written in the least Wallace-like manner imaginable. Is that a bad thing? If you just treat the book as a delivery mechanism for DFW facts (he voted for Reagan! he tried to convince his mom that Avril Incandenza wasn't based on her! the original draft of Infinite Jest was 750,000 words long!) then no, it's not a problem. And there's plenty of interesting stuff in there, even if you're mostly looking for insight into his work rather than his life. But everything that isn't solely grounded in facts here is pretty much useless. Because Max doesn't tell us how he came up with his interpretations, it's impossible for us to independently evaluate them. And when we're talking about a confusing subject like David Foster Wallace, an interpretation without a backing argument is worthless.

Here's one big example of what I'm talking about. Max's book spends a lot of time telling us about how difficult it was for Wallace to write, even before his later struggles with The Pale King. After a very productive start (he wrote a 480-page novel as just one of his two senior theses in college), he began to find writing a perpetual struggle. Teaching distracted him from writing, but he needed to teach to make money; his addictions to alcohol and marijuana made it hard to write, but when he quit, the experience of recovery also made it hard to write; and so forth. But after hammering this point into our heads for something like 100 pages, Max suddenly starts telling us about this new, long novel Wallace was writing. In Max's telling, Infinite Jest seems to come out of nowhere -- a long description of writer's block and drug/alcohol recovery is suddenly followed by Wallace having 250 finished pages of his new novel, which are so good that they make his new editor say he wanted to publish the book "more than I wanted to breathe." Whence this astonishing productivity?

In Max's telling, Infinite Jest was the product of a sort of conversion experience. Recovery made Wallace decide that he didn't like "irony" anymore and that he wanted to write something with a moral purpose, and this newfound sense of direction opened the floodgates of Wallace's creativity. But there's nothing like this sharp "ironic / non-ironic" division in the work itself. Max tells us that Wallace was trying to become more "conventional." But Infinite Jest is just as weird as anything he'd written before, except on a much larger scale. I also have a hard time seeing it as an "unironic" book, though I confess I don't really know what "irony" means, exactly, in this context. (I suspect Max isn't sure, either, but of course he never bothers to define or investigate the term -- that's not his style.) How did the depressed, moralistic recovering addict of Max's story write hundreds of pages of manic, blackly comic prose about increasingly grotesque episodes of familial trauma? Max tells us that Wallace was no longer interested in alienating and confusing the reader, the way he was in his earlier work; the real Wallace composed a book that takes months to read, leaves no reader-expectation unviolated, and actively strains to avoid becoming too entertaining. How do these pieces fit together? It's not that what Max says is wrong, just that it's one part of the apparent contradiction. A good biography would takes steps toward resolving that contradiction. This one doesn't even acknowledge it.

(Also, Max's book is really badly written on a sentence-by-sentence level, even by pop biography standards. Again, not a problem if you're just looking for info, but a bit disappointing if you're looking for a good, respectable discussion/appreciation of the subject matter.) -

la sua storia è diventata una storia di fantasmi

"Devo accettare il fatto che potrei essere incapace per costituzione di reggere un legame intimo con una ragazza, il che significa che sono o terribilmente vuoto, o malato di mente, o entrambe le cose" (corrispondenza privata)

"Succedono cose davvero terribili. L'esistenza e la vita spezzano continuamente le persone in tutti i cazzo di modi possibili e immaginabili." (da Brevi interviste con uomini schifosi)

"L'idea che tutti siano come te. Che tu sia il mondo. La malattia del capitalismo consumista. Il solipsismo compiaciuto." (da Il Re pallido)

biografia accurata di uno scrittore non convenzionale

quindi anche la bio segue più che altro un ordine cronologico, ma emotivamente parlando ci sono dei salti e delle ricadute che indicano il percorso sbilenco della vita di David, una vita fatta di incontri e di fughe, di lavoro e di dedizione, di libri scritti e cesellati, libri mai amati, semmai odiati appena dati alle stampe, di dipendenza e di noia, di corrispondenza con DeLillo e amicizia/competizione con Franzen, una vita dolorosamente poco vissuta, più che altro pensata, lui pensava troppo e viveva pochissimo, aveva sempre paura e questo si evince da ogni parola che ha scritto nel corso della sua carriera di scrittore e saggista e per via della sua paura alla fine ha mollato tutto a metà, come fosse un suo romanzo...

"puoi fidarti di me, sono un uomo di..." (da La Scopa del sistema) -

ELS-isa-GS haunted me but not because it tells of DFW, a brilliant literary titan, who suffered deep psychic trauma and depression but because of the phantoms shadowing the presence of this caricatured history. Everyone is mysteriously absent, hovering just beyond the periphery--his parents, his sister, his many gfs (Mary Karr) and his wife Karen Green, his literary peers (Delillo, Franzen, Costello, editors, agents like Bonnie Nadell), his students, his AA mentors, sponsors & therapists.

D.T. Max's weak treatment of DFW's literary work and vapid check-list style chronicle profoundly reeks of opportunism--that is, the old habit of the Hack riding the wave of a genius's legacy. Max's Acknowledgments hint at a greater interest in making the rounds--to mingle, schmooze, grip & grin--among the published/ing privileged than genuinely composing a worthy dimensional book-length bio on Wallace. Any well-attuned reader of Wallace could derive more from reading a couple pieces of his (non)fiction than from reading this 300+ page pablum. -

Well I really liked this book but, um, it's not really fair 'cause I wrote it. Thanks to everyone who has read it too and thanks especially for all the feedback. It's how we all learn!

-

I began reading Infinite Jest for the first time when my ex-wife and I were flying over the Atlantic Ocean on our way to Rome. This reading was my first experience of DFW, and I remember howling with laughter as perplexed Italians perplexedly looked at the nerdy guy with glasses who couldn't control his hysterical relationship with what appeared to be a copy of what appeared to be . . . a dictionary??!!!

I wasn't laughing at the tremendous material in DFW's very funny mega-novel but laughing with the joy of recognition. Never before had I read a writer whom I felt thought the way I thought. It was like DFW's thoughts were my thoughts, right down to the syntax, sense of humor, and moral and ethical concerns. It seemed like my fellow midwesterner was my best friend - and that we were going to have a long relationship hanging out together, through the medium of his books and, perhaps, through the medium of my books and articles. Who knows? We both loved the same writers. Maybe he'd pick up something I'd published on DeLillo or Vollmann . . .

The previous and somewhat self-indulgent two paragraphs are key to my reading of Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story because this is the first biography of a person whom I consider to be somewhat of a contemporary (DFW would be roughly ten-years my senior, if he were still breathing). And, since his suicide two days before my 36th birthday, on September 12, 2009, I've felt a gaping hole in my soul. And I don't mean to exaggerate this feeling of emptiness at all. It's as if a section of my being was removed from me on that day in September - and I know that I've never gotten it back.

I remember telling someone that DFW's suicide would send me into a tailspin. And it did. Shortly after it happened, I was experiencing severe symptoms from cardiomyopathy (a form of heart disease that will eventually result in a heart transplant and/or premature death). I lost my job and my marriage fell apart. I, seemingly, lost everything.

I also began to experience a flair up in the mental-health problems that have plagued me for my entire life. Multiple medications were tried - and multiple medications didn't work. I was - and still am, to a certain extent - suicidal.

Now, I'm not completely attributing DFW's fate to what I've gone through. I know that other factors were at work.

But what fascinates me is the way in which my story relates to his. I'm not claiming his brilliance for myself, and I realize that Max has constructed DFW as a character in this bio just as any subject of any bio is a character.

It only came out after DFW died that he - like me (I'm also a childhood cancer survivor) - suffered from serious health problems throughout his life. Mine were mental and physical, and his were mental, true, but I think that we both realized the fragility of life and the importance of life as a moral quest.

We were both good students. I had the drive to get a Ph.D. from a major institution by my mid-twenties, just as DFW did well in academia and published his first novel - The Broom of the System - when he was a wunderkind in his mid-twenties.

We also both used academic success and our intelligence as a way of dealing with the chaos and insecurities that bedevil contemporary US life. Knowing more stuff was a way of keeping the monsters of chaos at bay. We both read a lot, valued Dostoevsky as the greatest novelist who ever lived, raged against irony, and deeply believed, to quote Patti Smith, that compassion has a human face.

Consumerist America was our Hell. DFW tried to find ways out of it and the ironic stances it produced in his fiction and essays, while I tried to teach and write on books that sustained an ethical commitment to others while advancing the craft of fiction.