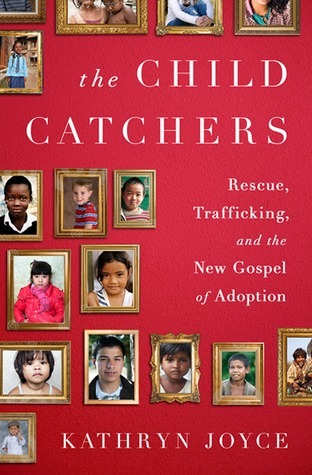

| Title | : | The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1586489429 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781586489427 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 332 |

| Publication | : | First published March 5, 2013 |

Adoption has long been enmeshed in the politics of reproductive rights, pitched as a “win-win” compromise in the never-ending abortion debate. But as Kathryn Joyce makes clear in The Child Catchers, adoption has lately become even more entangled in the conservative Christian agenda.

To tens of millions of evangelicals, adoption is a new front in the culture wars: a test of “pro-life” bona fides, a way for born again Christians to reinvent compassionate conservatism on the global stage, and a means to fulfill the “Great Commission” mandate to evangelize the nations. Influential leaders fervently promote a new “orphan theology,” urging followers to adopt en masse, with little thought for the families these “orphans” may already have.

Conservative evangelicals control much of that industry through an infrastructure of adoption agencies, ministries, political lobbying groups, and publicly-supported “crisis pregnancy centers,” which convince women not just to “choose life,” but to choose adoption. Overseas, conservative Christians preside over a spiraling boom-bust adoption market in countries where people are poor and regulations weak, and where hefty adoption fees provide lots of incentive to increase the “supply” of adoptable children, recruiting “orphans” from intact but vulnerable families.

The Child Catchers is a shocking exposé of what the adoption industry has become and how it got there, told through deep investigative reporting and the heartbreaking stories of individuals who became collateral damage in a market driven by profit and, now, pulpit command.

Anyone who seeks to adopt—of whatever faith or no faith, and however well-meaning—is affected by the evangelical adoption movement, whether they know it or not. The movement has shaped the way we think about adoption, the language we use to discuss it, the places we seek to adopt from, and the policies and laws that govern the process. In The Child Catchers, Kathryn Joyce reveals with great sensitivity and empathy why, if we truly care for children, we need to see more clearly.

The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption Reviews

-

We in the adoption reform movement have long known that big problems hide behind sentimental, idealistic rhetoric when it comes to adoption. Joyce does a fabulous job of bringing out the true complexity behind simplistic assumptions about the needs of world-wide "orphans" and what is in their best interest.

Too often, adoption fills the emotional needs of adoptive parents or worse, fills the pockets of baby brokers in the U.S. and elsewhere.

If you care about children's (or their mothers' and families' and communities') welfare, this is a must-read book.

If you are considering adoption, this book should be required for your home study.

If you are considering placing a child for adoption, let this book introduce you to information the agencies and maternity homes will not give you.

I found this book highly readable in spite of the sometimes labyrinthine complexity of the issues, policies and histories it explores.

Kudos to Joyce. -

This is an eye-opening investigation into the adoption market, both within the U.S. and globally—and as this book shows, it is very much a market, driven as much by demand as supply, and often resulting in exploitation. The book focuses particularly on the evangelical adoption movement within the U.S. The adoption lobby is strong here, and I suspect I’m like most Americans in having generally imbibed a pro-adoption attitude without realizing there was a lobby—but while the book doesn’t oppose adoption per se, it shows the serious problems in the industry and why taking children away from their natural parents is usually not the best way to solve the types of problems that lead to their relinquishment.

I was only vaguely aware of the popularity of adoption among evangelicals, which has been gaining steam for decades: adopting children (even by those who already have many biological kids) is seen as a way to gain favor with God, a way to convert the children, a solution to abortion, and a way for Christians to do something positive rather than just sitting back and judging others. The movement is rife with misinformation: for instance, telling congregants that there are hundreds of millions of orphans in the world whom they must save through adoption, when in reality these numbers are wildly inflated. If not invented altogether, they’re based on estimates of children who have lost at least one parent—most of whom, obviously, still have relatives to care for them.

Even when it works well, there are serious issues with an adoption-first model: taking off with the children is not actually a way to help a country or community, which many adoption advocates claim they’re doing. Most children being adopted internationally are not “orphans” (which seems obvious, particularly as most adoptees are under two; that’s a short span of time for two young adults to die), but instead come from impoverished families. Indeed, in many countries, poor families will use orphanages as a sort of boarding school (free meals!) during rough financial times, with no intention of abandoning their children.

The hypocrisy becomes clear when you note that international adoptions tend to cost tens of thousands of dollars, but that many of these families could be preserved with just a few hundred. An answer to the children’s problems that boils down to “rip them away from their families, communities, cultures and languages, change their names, and put them under the authority of some foreign family” will not be in the best interests of most children. But—even among families who aren’t grappling with infertility and believe their own motivations to be charitable—far fewer people would be willing to put up the funds to help families than are willing to spend thousands to get control of the children themselves. The children’s needs seem to be secondary here to those of the adoptive parents.

And that’s without mentioning the worst possibilities. In “boom” adoption countries, “child finders” often make a living producing adoptable children. Uneducated parents relinquish children without understanding the situation; their own cultural understanding of adoption tends to be a more flexible “it takes a village” arrangement, and they believe the children are simply going abroad for some education before being returned to them. In one family profiled here, an Ethiopian single father sent three of his seven children—girls ranging in age from 6 to 13 (though the agency claimed they were younger)—to an agency believing it was a study abroad program. The adoptive parents (who had been falsely told that he was dying of AIDS) eventually figured it out, but seemed to believe it was too late to change things and that he was fine with the girls staying (in an interview

elsewhere, the oldest girl stated that their interpreter told the family to keep the girls when the father actually asked for them to be sent home). The oldest suffered from depression, was sent to live with the adoptive grandparents, and ultimately moved out with friends; based on

a Facebook post from last year, the middle girl ultimately returned to Ethiopia as a young adult, while the youngest moved in with the same family as the oldest before taking her own life at 22.

Then there are the actually abusive families. There have been cases of adoptees murdered by their adoptive parents (other internationally-adopting parents seem to have identified strongly with the parents convicted in one high-profile case, which is concerning), and plenty more terrible situations that don’t rise to that level. Another family profiled here, a back-to-the-land, homeschooling Christian patriarchy bunch, had several children of their own before adopting several more from Liberia, survivors of its civil war. The kids were put to work on the family property and business rather than being educated, kept isolated on the property, and beaten and locked outside in the cold for punishment.

Another dark adoption underworld involves informal “rehoming,” in which adoptive parents who’ve bitten off more than they can chew give away the children to others, including strangers found on online “adoption disruption” forums. There’s a great, though horrifying,

series of articles about this practice. In the worst case scenarios this naturally leads to abuse, but even the “best” cases seem to involve overcrowded homes of families who either couldn’t formally adopt because they failed a home study, or lacked the money to do so. From a brief online search, there does not seem to have been legal action since to curb this practice.

Joyce mostly focuses on international adoptions, following the boom-and-bust cycle in several countries, particularly Ethiopia and Liberia. She also travels to Rwanda—which in a hopeful sign, seems to apply a lot more individual scrutiny without the corruption found other places, though their foster care program is still in its infancy, not great for children in the meanwhile. She also examines the case of South Korea, a highly developed country that as of this book’s publication in 2013, still had a major international adoption program. (This appears to no longer be the case.) This was mostly driven by extreme stigma against unwed mothers and their children, with most mothers wanting to keep their children but feeling unable to do so when they could be denied housing and jobs as a result, see their children discriminated against at school and later in the marriage market, etc. Of course, having international adoption as a release valve meant the country didn’t have to grapple with the natural results of its changing sexual mores; single parenting can’t become normal as long as no one is doing it.

The discussion of domestic U.S. adoption follows a similar trend. From 1945 to the Roe v. Wade decision in 1972, unwed women were under intense pressure to give up their children for adoption, and women placed in maternity homes were often abused, exploited or saw their children stolen from them after birth. As a result, some 20% of white women giving birth outside of marriage relinquished the babies, though many subsequently suffered from grief, depression and regret. (African-American women relinquished far less often.) These days, despite enticements to birth mothers such as open adoption, very few are interested in relinquishment—around 1% of unmarried white women and a statistically insignificant number of black women.

However, among the evangelical community, many of those antiquated pressures still exist. Joyce profiles one young woman who became pregnant with her boyfriend at 19, and whose parents sent her to a small, evangelical maternity home. There, she was put under intense pressure to give up her baby, introduced to the prospective adoptive parents and guilted about disappointing them when she expressed doubts, and ultimately given misinformation about her right to change her mind. Years later, she was still fighting unsuccessfully for access to her son, whose evangelical adoptive parents went on to adopt many other children as well.

What’s striking about all this is how much adoption advocates seem to want to drum up adoptable children. Joyce spends a good portion of the book interviewing these people and quoting their expressed views: birth mothers who choose to keep their children are called “selfish” and “immature,” while giving up the children to be raised by others is presented as “an act of sacrificial love.” Crisis Pregnancy Centers—most commonly known for their sleazy tactics to stop women from having abortions, such as pretending to schedule them and waiting out the clock—also push adoption. But the reality, for those who see adoption as a “middle ground” solution to abortion, is that very few women are interested. A 2010 report showed that annually, an average of 14,000 infants are relinquished for adoption, while there are 1.2 million abortions and 1.4 million women keeping their children (I assume this only counts unplanned pregnancies, as the total births in the U.S. in 2010 were

4 million.)

Obviously, this book is full of eye-opening information, and a lot of food for thought! It’s a very journalistic account, by which I mean both that it’s engaging and readable, including interviews with many people, but also that it doesn’t have any “main characters”; I expected it to follow a few stories more in-depth throughout, which it does not. Instead it is organized topically, presenting the abbreviated stories of adoptees and families along with the doings of agencies and activists. Very thorough, extensively sourced, and I think quite balanced as well: Joyce clearly sees a lot of problems with adoption, particularly when it comes with a sense of entitlement to the children of the disadvantaged or a desire to “save” them only if it can be done by controlling them. But she also generally seems to give adoptive parents the benefit of the doubt and to support responsible adoption—while recognizing that the best result for most kids is to stay with their birth families, and that helping kids should generally involve supporting families.

I would have liked to know a little more about outcomes in birth vs. adoptive families. Joyce notes that 6-11% of U.S. adoptions are “disrupted,” which seems to mean rehoming; obviously, some parents also pass their biological children on to other relatives or institutions (though not internet strangers, I think!), while others abuse or neglect them, so it would have been interesting to see statistics in comparison. It also would have been nice to have a chapter about foster care and adoptions from that system, which is quite different from what’s shown here.

At any rate, I went into this book under the vague impression that the biggest problem in international adoption was racial insensitivity/cultural ignorance, and came out a whole lot more informed and horrified. And with a lot of new opinions (not discussed in the book, which hews too much to journalistic standards to make policy proposals):

- Demand for adoptable children clearly exceeds supply, so families that already have 4+ kids, whether through birth or adoption, really shouldn’t be eligible to adopt any more unless those kids are their relatives or there’s a finding that no other homes are available to them. These “families” with 10, 15, 20 kids, most of them adopted, hardly sound like a family experience at all for the adoptees.

- People who intend to raise the children in some fringe lifestyle also, it seems to me, should not be eligible unless the kids are their own relatives, already members of the group, or are able to give informed consent.

- Homeschooling seriously needs to be more regulated to make sure actual learning is happening. The idea of kids unfamiliar with the country being isolated through homeschooling is particularly concerning, and it seems like teens should have a say in whether to participate.

- Agencies should be required to take responsibility and find a suitable new placement if the adoptive family is unable to care for the children. Plenty of animal rescue organizations require return if you can no longer keep the pet; it’s bizarre to me that we have less protection for human children.

- That said, the power these private agencies have is also horrifying: they collect the kids and choose the parents (in the case of evangelical agencies, seemingly based largely on religious ideology that may not be shared by the child or their birth family), often provide false information on both ends, and have no obligation or inclination to pick up the pieces afterwards. Government child welfare services have all kinds of problems but still seem far more suited to govern adoptions than these people.

- I can no longer judge people seeking expensive fertility treatments instead of adopting. There are kids out there who need homes, yes, but there are more families seeking very young children than there are adoptable children to meet demand, and not everyone is cut out to take on a traumatized or special-needs older child.

A very long review, because this is such a serious issue and was such an eye-opening read for me! Although it was published in 2013, much of what’s described here still affects people in 2022, and it’s very much worth a read.

EDIT: I’m retroactively rounding this up to 5 stars. Also, I read

Finding Fernanda after seeing it referenced in this book, and would recommend it as a strong follow-up with a focus on a particular human interest story. -

This is the best book about adoption ever written. Many excellent books have been written on the topic that address various aspects of adoption. However, Kathryn Joyce skillfully weaves together that history with today's grim realities on the subject. This book should be required reading in the White House, the State Department and Congress. Though adoption has become a multimillion dollar industry it operates with almost no meaningful regulation by the US government. Policy makers, hounded by adoption industry lobbyists and their allies, have bamboozled politicians and unwitting consumers creating a scenario of consumer abuses that would be soundly rejected in any other field. This lack of vigilance has translated into a global lack of confidence in US policy in this area that threatens to end this worthwhile social practice altogether. Joyce lays out the myriad ways in which adoption - whether private domestic, foster care or international adoption from a dizzying array of foreign countries - has become a big business at the expense of families - both birth and adoptive. Every family who has adopted or is considering adoption should read this carefully researched sobering book about an important social practice run amok. In fact, it is a must read for anyone who cares about children, period. To say it is filled with food for thought about our collective negligence as a country for allowing these abuses not just to continue but escalate would be an understatement.

-

I really wish I could write book reviews instead of blather on about not much.

The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking and the New Gospel of Adoption, is the best book about adoption ever written. (Full disclosure: I'm mentioned in the credits 4 times). Kathryn contacted me years ago when she was in the early stages of the book. I told her I didn't know much about international adoption outside of the murders of Russian adopatees in the US, but gave her a list of people who did. I'm happy to see that some of them were sources and quoted. I do, however, know quite a bit about "Christian" adoption-for-conversion and the "orphan crisis" and have written about it a little bit (particularly Haiti). Kathryn just nailed it. It's a book that I would have loved to have written.

The chapter on Haiti is excellent. Most disturbing for me were the chapters on Liberia and Above Rubies, and the next chapter "Pipeline Problems." I knew nothing about Liberia and the amount I knew about pipeline problems pales in comparison to what Katheryn has written.

International Adoption is a out-of control corrupt "social child welfare" practice that needs to die. In the old days the US (and other countries) raped less fortunate countries for natural resources and material goods IA, however, as operated by US adoption thugs(usually under the guise of "christian" endeavor) is I suppose more like date rape--child expropriation by "friends." Not in the book, but a couple years ago I attended a NCFA conference where do-gooder adopter lawyer Elizabeth Bartholet informed us that parents and countries that send their children to other countries empower themselves. IA is all about Christians (and others) who view the world through the lens of the middle class Protestant ethic. The amount of money it takes to complete one IA could be used to preserve dozens of families. If course, if IA were to finally flop--and it seems to be for many reasons--the adoption industry will ramp up child expropriation at home.

Apparently there is something quite horrible about children being reared by their own parents.

Five stars, and if I could give more I would! -

Finally, 2013 delivers me a truly excellent, thought-provoking and challenging book. Immaculately researched and painstakingly balanced, the book is like a saunter along a maze of interlocking paths of good intentions, which all seem somehow, to lead inexorably to someone's hell. Joyce's book, however, isn't a blanket condemnation as much as an effort to raise the problems, in the hope of starting a conversation that might make things better.

I've had the Child Catchers on pre-order for some time, and immediately dropped my other reading when it arrived winking at me on the Kindle. Joyce is the only authoritative US feminist journalist covering religion, and as someone with a deep interest in how ideas about gender are both reflected in, and influenced by, religion, I tend to read everything she writes. In the last five years, I have also noticed the immense growth in adoption, particularly from Africa, among evangelical "mommy bloggers", and I was looking forward to a more systematic coverage of where this particularly theological orientation came from.

Joyce does cover this off, but the book is much more than that. She delves deeply into the phenomenon of US adoption from the 1930s onward, both domestic and international. Raising questions not only about the involvement of evangelical churches in adoptions, but of adoption agencies. Joyce did more than 200 interviews for the book, and you can see why. The book is populated with people trying so hard to do good, in a very morally murky world. Joyce is at pains to present the view of all the participants - adoptive parents, "birthmothers", church representatives, adoption agencies, church and secular welfare workers, and of course, adult adoptees.

I have no intention of summarising the content of the book in this review - go read it! - but the issues raised bear some discussion.

Going in to the book, I had few opinions about adoption. Like most people, I know adoptive parents, adoptees and a couple of people who relinquished children to adoption. I have enormous time for the adoptive parents I know. I have always assumed adoption is a "win-win" scenario in most cases. But this presents an equation that seems somewhat equal - adults who wish to parent on one hand, and children without parental support on the other. But where the former group have economic power, and the latter do not, the result is more like a commodity market than a social program.

A simple example of this is the growth of orphanages in the developing world. Orphanages attract very large amounts of funding from the West. Who doesn't give money to support an orphanage? But orphanages are also widely known to be simply the worst environments to raise children. In Australia, we foster kids out because it is better for them (acknowledging the many issues). But in places like Cambodia or Uganda, fundraising for an orphanage is much easier than attracting funding for a new social program. And, of course, adoptive parents want to rescue children from orphanages - which they know are terrible environments, and orphanages are easy for adoption agencies to work with. So the orphanages remain as key parts of the strategy, even in countries making a concerted effort to develop more stable programs based on family support, foster care and domestic adoption.

At the heart of Joyce's argument is one of numbers. The evangelicals claim in excess of 200 million orphans internationally (counting all kids who have lost ONE parent - the number who lost both is less than 10% of that, and the number with no extended family care less again), and calling for adoption as a social need. Joyce points out brutally, however, that in actual fact the number of parents who want to adopt vastly outstrips the number of children available for adoption. The demand is coming from the West - for children, the strongest social need is for better support for families locally, not for someone to take the kids away. This difference in perception - builds on neo-racist theology in the evangelical churches that views every child adopted as "saved" from a barbaric (*cough* heathen *cough*) environment.

Time and again, Joyce describes situations where, no matter how individuals and governments try to avoid it, the sheer amount of money that adoptive parents pour into a country distorts the local view of adoption - where communities calculate that aid and development money follows adoption, and giving up kids for the greater good becomes part of a strategy.

Joyce is largely successful in distinguishing between the situation of most individuals within this system and the broader dynamic, describing how several heroic adoptive parents navigate the system and the injustices with compassion and an attempt to find the best solution for the children in front of them, which may well be adoption in the U.S. Orphans created by the system, still, in many cases, remain orphans.

She avoids, frankly, dwelling overly on some of the more sensational coverage - the killings of three adopted kids by evangelical parents in the US, which received a lot of media - are only mentioned in passing, for example. She does cover with some clear fury the worst abuses associated with the following of the Above Rubies crowd, including not filing paperwork within the US, so children adopted from Liberia in particular, can be abandoned without legal consequence, while the children end up effective illegal immigrants, unable to go to college, or get a driver's licence.

Perhaps the most devastating chapters, however, involve the stories of relinquishing parents in wealthy countries - the US and South Korea. Joyce de-constructs how the anti-abortion pregnancy advisory services are placing an ever-increasing emphasis on convincing women to relinquish - using hefty doses of guilt, deceitful legal practice and stereotype (what future can you offer?) to do so.

There are few solutions offered. Some glimmers of hope in more localised programs in countries such as Rwanda, and legal changes in South Korea. But what seemed to me as the central issue - how do we better support children, and those who want children, in a non-market way - is not directly tackled by the book. Is this about building a global village? Do we have to accept that being part of a broader family is a better solution than transplanting kids from one nuclear family to another? I honestly don't know.

There are a couple of quibbles - I always have some!. Given that the central question is that of what is best for a child, I wanted more experiences of adult adoptees, and perhaps in particular, those who felt more positively of their experience. The shocking statistics covering the decline in white American women relinquishing are all measured in never-married - it would be nice to what extent the growth in de-facto couples parenting distort those - but really, one of the most important, and troubling, books I've read in a long time. -

If you have thought about adopting a child, you owe it to yourself to read this book. If you have adopted a child, particularly in an international adoption, all the more so. Please note that I'm not suggesting you will enjoy the ride, as the author deftly sucks you into a whirlwind of corruption committed in the name of rescuing orphans.

You may find yourself trying to argue with the book's conclusions, with the excuse that these are only the horror stories, that most adoptions turn out well. Most of the time that's true, but ends don't justify means. By describing the worst cases of children caught in a system that disregards their rights, 'The Child Catchers' devastates the rationalization that adoption saves orphans. Taking children from families in developing countries is tragically common; it's at best an inefficient method to make them better off, and at worst child trafficking driven by the profit motive.

This book will not be prescribed as a sleep aid to adoptive parents. It may cause nagging thoughts about whether what you were told about your child's origin is true enough. After reading, you may ask yourself how to live with the ambiguity of never knowing for certain. Perhaps you'll do what I did: initiate an(other) inquiry to find out what happened to the child you love so much, before the adoption.

Knowing the scale and scope of deceptions practiced against first families in developing countries, as well as adoptive families with the best intentions, may trouble the reader. As it should. There are troubling patterns repeated in the business of international adoptions, and Kathryn Joyce has documented them thoroughly. This book bothered me. Strongly recommended. -

As an adoptive parent this was both a tremendously useful and a very painful read. Many adoptive and prospective adoptive parents will benefit from it, refining their standards about adoption, dispelling some illusions and ultimately taking steps towards a more ethical adoption. Sadly many more will be horrified and averted from adoption alltogether.

This last effect of the book is the unfortunate one. The writer gets carried away by its polemic stance against the evangelical movement in the US to generalise and attack adoption in general. It is sad that her attack feel ideologically driven in many instances. Her bias was painfully evident in the Rwanda vs Ethiopia part where inaccuracies were blunt. I attribute this more to bias rather than malice. Her attack on adoption is based mostly on anecdotal evidence and case studies of international adoptions gone horribly wrong. Arguably such cases are the result of an extensive research by the author but I feel they paint a grimer and more desperate picture that the actual situation.

I would urge prospective adoptive parents to read statistics and scientific studies alongside case studies from this book before proceeding or abandoning an adoption plan.

Being a secular person myself I find little consolation on the theological defence of adoption. In that respect I totally support the author's viewpoint. But what I would hope from another secular person with humanitarian values (like Kathryn Joyce) would be advocacy for a international adoption REFORM rather than a international adoption ban.

Adoption if practiced ethically can be a paragon of good. This books says otherwise. -

The measure of a good nonfiction book for me is to make me think about something differently. It's fair to say that after reading Kathryn Joyce's book, I will never look at adoption in the same way again. Though I'd always thought about adoption as something admirable but difficult, I didn't really have a great sense of how deeply the evangelical Christian movement was committed to adoption as means of spreading the Gospel. This is why you see tea party conservatives gather their multicultural families around them in campaign ads -- they're part of the deep mythos of rescuing children for God.

This is all a nice idea, of course, but the demand created by evangelical families has created the incentives to do a lot of really terrible things. Joyce carefully documents numerous instances of families who discover that the children they're adopting, often from abroad, often have living parents still, and the cultural disconnect about the permanence of American adoption often leads families to think they're merely sending their children away to American boarding schools rather than agreeing to give up their children for good. Joyce carefully does the math. The number of truly unwanted children who have no living relatives, even by the highest estimates, is far exceeded by the number of Christian adoption families.

She also dives into the motivation behind Crisis Pregnancy Centers -- that the idea isn't merely to convince young women to carry through with their adoptions but also to give those children up to the insatiable demand of Christian families who want to rescue children. This is all too often ineffective. It's true when you look at the data. Poor women in America are the most likely to have unintended pregnancies, but they are also not very likely to give their children up for adoption, because of course, they want to keep their families intact. It makes the "you can always choose adoption" slogan pro-lifers so often fling around as an argument ring hollow.

The book isn't perfect. She looks at one adoption gone awry where a young women signs away her child under false pretenses and spends the rest of her life longing after a child that is hers but no longer belongs to her. Joyce barely addresses the adoptive family in that chapter. While it's easy to paint one side as a villain and another as a victim, adoption is itself an extremely complicated issue, where both sides often struggle.

In the weeks since reading this book, a high-profile case popped up in Arkansas, where a Christian politician's family

adopted children from the state's program, only to think they were

possessed by demons, and gives them up to another family, where the girls are molested. To understand that case, it's important to read this book. Joyce spends time on the adoptions that don't work out, on the families who take on the mission of adoption but aren't prepared for its challenges. And because they are devoted Christians, often the only explanation for people trying to do what they see to be the right thing under God is to blame the Devil. Unfortunately, the world is much more complicated than that. -

I didn't think that Joyce (or anyone) could write a book that could make me as angry as "Quiverfull". I was wrong. A look at how the evangelical view of conversion to Christ by adoption has wreaked havoc around the world, as mothers, fathers, and families are lied to and children turned into supply and demand commodities and how adoption agencies make millions at their expense. I'm no fan of the anti-sex movement in this country but Joyce puts together a terrifying picture of how CPC's funnel pregnant women into coerced adoptions. How the evangelical movement's hope that the absence of sex education and blocked access to birth control and abortion will somehow mean more babies for them to adopt from poor white women (US women of color don't factor in this domestic adoption equation). I'm getting even more pissed just writing this review. It's so nice that evangelicals seem to have no moral center and 'lying for Jesus' is acceptable to get whatever you want (not really, that's sarcasm).

-

I'm not really sure how many stars I want to give this book. On the one hand, I am so glad I read it and I highly recommend it because it contained so much information, and gave some really good insight into some of the aspects that play into adoption. But on the other hand, there were some parts that were really glossed over, and some acceptance of groups like UNICEF that weren't really fully explored or addressed. While Ms. Joyce points out some very troublesome and problematic aspects of adoption (not just those that take place internationally, but also with in the U.S.), she ignores other problems that arise out of some of the solutions that she seems to embrace. At one point, she discusses a country that is dedicated to minimizing the number of out-of-country adoptions, and gives an example of a girl who would have been eligible for adoption, but was not, because her birthmother was known, but was in a mental institution. Joyce implicitly approves of this outcome -- that the girl would likely lose all ties with her mother were she to be adopted abroad. Yet, obviously the mother is not able to care for her, and there's no indication that she will be able to do so in the future. How is the girl's situation better than being adopted abroad?

Similarly, she seems to approve of measures that require that all efforts be made to first find genetic relatives of the child who will hopefully care for him or her, before the child is eligible for adoption, sometimes even requiring these efforts to go on for 6 months or more. However, who is to say that a biological relative is the best caregiver for such a child? In many circumstances, a birthmother may relinquish or abandon a child because the family disapproved of the pregnancy or may have been abusive or otherwise dysfunctional. What would be gained by seeking these same relatives, from whom the mother might have wanted to hide the pregnancy (especially in some societies where an out of wedlock pregnancy is particularly shameful)?

Another point, although minor, is that she references a conference about adoption and repeatedly refers to it as occurring at NYU Law School. This is incorrect. I have attended the conferences, and they are at New York Law School, which although it is still in New York, and is still a law school, is an entirely different law school than NYU's law school. There is an undertone to the discussion of this conferences that it is an elite conference, partially due to it's affiliation with NYU, but there is no such affiliation. Again, I admit this is a minor point, and the conference attendees could still be referred to as "elite" in that they included many government officials and lawyers, policy makers, doctors, and professors who work in fields related to adoption. But the repeated incorrect reference was nevertheless slightly troubling.

This book tackles a huge array of issues in adoption, some of which are more problematic than others, and Joyce sometimes conflates situations that aren't really similar. Some issues are pointed out as problematic, when I don't believe they are necessarily so, or not nearly as much as she seems to believe.

On the whole, however, the religious calling to adopt is a huge problem in that it creates this demand that cannot be fulfilled and leads people to adopt for the wrong reasons. People should not be adopting because they think they are saving a child, or because they think it will somehow curry favor with God, or because they think they are somehow performing a good deed. They should adopt only because they want to parent a child. It is troubling how many people are becoming involved in adoption for entirely wrong reasons, and the results of this are too frequently tragic for everyone involved.

In addition, the idea that adoption issues really stem from women's rights (or lack thereof) and women's inequality is very insightful, as is the observation that poverty, together with women's equality, are really the biggest issues to address when attempting to tackle the plight of children who live in dire conditions. -

First, I worked for a private, Christian adoption and foster care agency. Although this agency was Hague-accredited, and partnered with Child Welfare in the State of Oklahoma, I did hear lots of the "Orphan Crisis" rhetoric (the focus of the early part of this book) from our clients. Fortunately, I heard our staff correct a lot of these, but the misinformation remains rampant in the upper-middle class, suburban evangelical churches our clients attend(ed). I was glad to see the author dispel with the myth of the "Orphan Crisis" through facts, figures, and stats, and that she did not shy away from detailing the unfortunate outcomes of the well-intentioned. She does well to differentiate the actors in the system of international adoption--from the misguided "evangelism by adoption" crowd, to the intentionally deceptive adoption workers, to the racists/colonialists, to the downright abusive--without letting any off the hook for being (willfully?) ignorant or unexamined.

Two major critiques:

1) This book is unnecessarily long. The journalistic format seems to be the author's attempt to present the problem to the reader as a "discovery," but much of it could've been condensed to brief anecdotes. This book would be better at 1/3 the length.

2) The author overlooked related practices in the private adoptions, and State Foster Care systems, because international adoptions is the sexier story. Bio-parents here in the U.S. are facing similar kinds of pressures the international mothers and families are, resulting in the same kinds of divorcing of children from the culture(s) into which they were born. She mentions ICWA, and hints at MEPA, but does not mention the problems in our own backyard.

In sum, with my first major critique heeded, this book could be half as long as it is, while being more comprehensive in its rebuke of evangelical mindsets and practices that lead to the unwanted break-up of families--all in the name of spreading the Gospel. -

The information in this book would be better covered in a magazine article. It seemed very long and redundant.

That said, the story of adoption needed to be written. It is so tied up with what women really need, to be supported both culturally and financially. When I was young, girls who got pregnant were sent away and never saw their babies again. There were plenty of babies for those who wanted to adopt. But the 70's happened and abortion became legal so there was a real shortage of adoptable infants in this country.

International adoption became prevalent, with eager parents moving from country to country as the laws and regulations changed. Unfortunately, it became very expensive and lucrative. Then the fundamentalist churches got involved and touted it as doing God's work and a ticket to heaven. Then people began creating extremely large families, often using the adoptees as servants.

I am privleged to know Deann Borshay, aka Cha Jung Hee, who produced the documentary "Third Person Plural."She was adopted from a Korean Orphange in 1966 and raised in Fremont, CA. But, the Borshays were given the wrong girl. It was common for mothers to leave children in orphanages for short periods of time when they couldn't afford to feed them. The girl they were expecting had been picked up the day before so the just grabbed another girl the same age and sent her to America with a new Korean and American name. After much counseling, Deann was able to find the courage to return to Korea and find her original family.

I also know several very successful adoptions, both domestic and international. I hope we can enter a new era where women who want to keep their children are given the support they need to make that possible. And people who are unable to have a child will be able to adopt a child who really needs a family. -

This book is very repetitive and I think the point could've been made with fewer stories. However, the overarching point of the book is an important one and one that any family looking to adopt should consider. Good intentions, self-serving emotional needs, little preparation and the notion that adoption is a biblical calling have driven adoption to become a very lucrative business that may not be best for adoptees. Basically, we are dealing with a broken system, she makes that point repeatedly. A better way to help poor/vulnerable children is to focus on care for their families and their communities, I think is at the base of what she's getting at for a solution, although she doesn't dig deep. I would argue that local churches are the best place to start.

-

Very difficult to read as an adoptive parent. I felt like the author's view was *very* one sided...Much of the information was useful, but she was very harsh one adoptive parents.

-

Riveting. The next person who blithely suggests how great adoption is, and how selfish women are who chose abortion, will undoubtedly receive a recommendation to read this book.

The book starts by questioning the ethics of unregulated international adoptions - situations where children who have living parents or relatives who may want to care for them may be "rescued" to "better lives" with coincidentally rich, white American families - and continues on from there. It details the supply chain (American Christians' demand for "orphans" far outpacing the actual "stock" of existing orphans) and how international adoption - couched in "savior" rhetoric - nearly always trumps the needs of existing poor families, and even the needs of the children themselves. Coerced adoptions, baby snatching, paternal rights illegally terminated, the eternal religious trump card, and baby profiteering are laid out with convincing evidence of each. Reading about adoptions from Ethiopia, which I have observed happen from this end, reinforced the validity of the criticisms. Joyce is not making this stuff up; it is happening right now.

The end of the book focuses on Rwanda in particular, along with other groups who are engaging in ACTUAL child-centered orphan care. The case for family first, domestic adoption second, and international adoption as a last-resort is clearly laid out, and policies which protect children and families from becoming commodities are highlighted.

If you care about adoption, you need to read this book. -

I stumbled on this book as I was reading thread after thread of debate about U.S. abortion law, including the recent draconian laws passed in Alabama. I knew very little about adoption other than the coercive tactics women endured in the 1950s and 60s. I knew even less about international adoption.

Combine poverty (Guatemala, Ethiopia, Rwanda), with evangelism; add a dose of social shame (South Korea and the U.S.); mix a splash of colonialism with a big profit motive and you have The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption. I had no idea that many (maybe most) international adoptees are not the orphaned, homeless children you imagine. They have families, sometimes both parents who have been hoodwinked into giving them up, often believing that their kids are going to be away temporarily. The rescue-poor-children mentality of American adoptive families overlooks the fact that the money many families pay to adopt children internationally would be much better spent alleviating the conditions that cause family poverty in the first place. As one country cracks down basically selling its children to American families, another pops up in its place.

Aside from the appalling deception that brings international children to the U.S. and thus tearing kids from their native cultures, we still have many communities coercing young, naive American women into giving up their children.

This was an eye-opening book. It certainly changed my attitude toward adoptive families who may knowingly or unwittingly have contributed to a great social injustice. -

This book certainly makes you think hard about international adoption. It's an area that seems rife with abuse, mostly in that many of the "orphans" adopted are not really orphans at all, and that often, parents are lied to about where their children are going, and made to think they are going to America on some kind of educational exchange. There were also fairly horrifying stories of families who adopted many children at once from Liberia or Ethiopia, and then were not able to handle the children, and either sent them back or passed them along to other families, or in some cases, used them almost like slaves.

Like another book by Kathryn Joyce I read, though, this book is marred for me by being more about official policies than actual families. Joyce often seems to feel that the official stance of an agency is how all the people using the agency feel. I get the feeling she is not sometimes able to get interviews or spend time with actual families that have adopted, maybe because she is so strongly and obviously opposed to what they stand for.

I appreciate books like this being written, and exposing things that need to be exposed, but I wish Joyce was a bit more balanced and a bit more flexible in her writing. -

This is an exhaustively researched (and sometimes just exhausting) expose of the emergence of a social calling for some evangelical American Christians, and the sometimes troubling ways their demands have been fulfilled.

Some large-family proponents have come to see adopting children from the developing world as not only rescuing the children, but also saving souls and socializing more human beings into their belief systems. On the surface, there's not too much to argue with here. I would rather see religion focus on doing good works; every time I see a huge billboard telling people they will go to hell if they study evolution, I think about how that money should have been spent on a food pantry or clothes closet.

However, what has been happening is some developing-world parents are being told their child is going to America on a study program, and instead their child is presented as an orphan and offered for adoption--never to see their homeland again. Once the young people gain enough English skills to tell their true story, their American parents may be abashed to learn the stories they were told of their child's origins were false. It's a difficult issue that involves exploitation on multiple levels. -

Full disclosure time. I have two cousins who are transracial adoptees. So I came into this book with some inherent bias. That being said, I was more than willing to give it a shot, especially since my colleague/friend Tami was singing it's praises and told me that I definitely had to give it a shot. So I immediately requested it from the library.

Basically this book is a look at the Evangelical movement and it's comparatively recent obsession with adoption. The conservative Evangelical movement sees adoption as not only putting money where it's mouth is regarding it's anti-abortion stance (in a 'Well maybe we WILL adopt all the babies!' kind of way), it is also, quite frankly, indicative of the idea of spreading the word of God to as many people as possible. This book examines the consequences of this movement's love of adoption, and exposes corruption within the adoption business. And yes, it is indeed a business. Stories from Haiti, Ethiopia, South Korea, and even here in America relate tales of adoption not always being the 'win-win' situation that it has been painted to be in situations like this, and points out that more often than not these children are not 'orphans', but victims of a society that makes it very difficult for their parent or parents to keep them based on global power, misogynistic cultural norms, and the promise of Western salvation imposed upon others.

Whew, right? I found myself fairly angered and frustrated as I read parts of this book. From adoption agencies in Haiti basically taking children by the droves after the 2010 Earthquake without even trying to figure out of they were indeed completely orphaned, to women in South Korea pressured to give up their babies because of their culture frowning on single motherhood (and the shaming that goes with the grief of losing their child), there are multiple horror stories that show that not all adoption agencies care about the children and their welfare, but more about the money that can be made. I was also equally disturbed by some of the stories of Evangelicals who collect children from all over the world and almost use them as props to show how NOT racist they are, or stories of adoptive parents physically abusing their adopted children for being 'willful'. Or domestic agencies trying to shame teen mothers into giving up their babies and then lying to them about how much time they have to change their minds, or, oh, having them sign things while under medication to hurry up the adoption process. Or adoptive parents who try and erase the culture their adopted children came from. OR how about the whole 'her uterus, our hearts' mantra that's been going around Evangelical adoption circles, as if a child's biological mother is nothing more than a uterus and that 'fate' had picked them to be the 'actual' parents long before the child was even born.

Do I have problems with adoption? Not as a whole, not as a concept, and certainly not as a practice. On the contrary, I am very much in favor of children finding homes when they have none, and people who are unable to have biological children for whatever reason (or those like my aunt who wanted to be a mother but pregnancy isn't in the cards for other reasons) having an option to fulfill the dreams of parenthood. I'm also very much in favor of it coming about because the biological parent or parents really does honestly feel like they cannot raise this child, outside of coercion, pressure, shaming, empty promises, and fear of consequences from society or those close to them. And I really would like it if adoption agencies took their pages from the place my younger cousin was adopted through, a place that works VERY hard to make sure that the adoption is in the best interest of everyone involved. I think that one of my issues with this book was that it didn't really look at it as much from the side of the adoptive parents, and kind of downplayed the idea that they too would be capable of being hurt in some instances, say if the biological mother were to change her mind. That was almost written off as irrelevant, and while I agree that a biological mother does have the right to change her mind, I don't think it's too fair to imply that the adoptive parents pain wouldn't be as much as the biological mother's. That seemed unnecessary to me.

THE CHILD CATCHERS was a difficult, but very informative read. I certainly recommend it to those who are curious about the history of adoption, and those who haven't really thought about it as a tricky issue. Because it is. -

I had just finished reading a new book about adoption called "American Baby" by Gabrielle Glaser when another adoption-related book caught my eye -- recommended by Nora McInerny (of the podcast "Terrible Thanks for Asking") on her borealisbooks Instagram account.

It took me longer to get through "The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption" by Kathryn Joyce than my 24-hour speed read of "American Baby" -- it's a longer book, with an incredible level of detail to wade through -- but it was still an absorbing read and a solid work of investigative reporting. Joyce examines how Christian churches -- mostly Protestant evangelical denominations, but also Catholics and Mormons -- have become a driving force behind the rise in both domestic and international adoptions. Those seeking to adopt now include not just infertile couples, but families who already have biological children but feel "called" to adopt one or more (sometimes many) children.

There are several key reasons why adoption has become a popular cause in Christian churches, which Joyce expands on throughout the book. First, there's the idea that adoptive relationships mirror the relationship we have with God (God has "adopted" all of us as his children). Second, adoption has become a big part of anti-abortion politics (Christians urge women to put their babies up for adoption instead of having abortions, so perhaps they should adopt some of them themselves?). Finally, adoption is seen as a means of fulfilling "the Great Commission" -- the Biblical mandate that Christians spread the Gospel (which commands them to care for widows & orphans). Effectively, Christians see themselves as "saving" the children they adopt twice -- first, from a life of poverty and neglect, and second from a life without God.

Unfortunately, increased interest in/demand for adoption has led to supply issues, and increased pressure to find more and more babies and children to adopt. Fewer children are available for adoption in North America today (because of better/easily available birth control and safe and legal abortions, as well as reduced stigma around single motherhood) -- but mothers at home and abroad (Joyce details past and present adoption programs in South Korea, Guatemala, Haiti, Ethiopia and Liberia, among others) are (still) being pressured into relinquishing their children for adoption, often without knowing exactly what they are agreeing to.

The numbers of "orphans" supposedly needing homes varies wildly, depending on which sources you consult and how you define "orphan." (Some suggest that any fatherless child might be deemed an orphan -- i.e., single mothers are, by definition, unsuitable parents.) Joyce makes the case that many children being adopted from abroad are not "true" orphans: many have living parents, siblings, and/or other relatives who might care for them -- some of whom believe their children are being given the opportunity to attend school in the States and will return to them in a few years' time. While many families are sincere in their desire to adopt, and many children are happy with their new families, there have also been failed adoptions and cases of physical and sexual abuse. All this has given rise to some interesting new movements among adoptees and birth mothers to reconnect adoptees with their birth families and cultures, and to influence adoption policy.

If you're interested in the subject of adoption -- or telling childless/infertile women like me that we should "just adopt" -- you need to read this book. (It was published in 2013, and I find myself wondering how much -- or how little -- has changed in the years since then?) I consider myself fairly well read on the topic, but this was still an eye-opener for me in many respects.

4 stars. -

Joyce brings to light the plethora of illegal and unethical practices that occur when adoption is treated as a big business. She does a particularly good job framing adoption as a largely ignored feminist issue and something that should be a larger part of the reproductive debate and discussion on the role of women in societies. She also breaks the myth of adoption as philanthropy, which it is decidedly NOT. It is an important life decision that affects the adoptee, adoptive parent(s), birth parent(s), their extended families, their communities, and their countries. It is an industry that is often poorly understood, with only a handful of people shaping the narrative. For those with no previous education on these issues, some of the stories and abuses could be extremely disturbing to you. Lean in to the discomfort, as it's how we learn to do better.

The larger purpose of the book was clearly to understand the business of adoption (mostly international adoptions) and where it goes wrong. She succeeds most admirably in this. It might have also been helpful to offer more alternatives or solutions to how improvements can be made to the adoption system, which tends to heavily prioritize the needs of Western adoptive parents over adoptees or birth parents. I wish she had included more of the adoptee perspective as well, but they do get peppered in as appropriate. I also hoped for more hard statistics on the scope of the problems she presents, as anecdotal stories do not comprise the whole picture. Honestly though, I imagine that kind of information is difficult to aggregate.

Understandably, the stories she highlights tend to have more sensational elements to them (though she presents them without it feeling exploitative). I question the universality of some of the stories of adoptees and their adoptive families (I do not question their validity). I see why they were included anyway, as they are the kind of stories that make you want to throw the book against the wall in disgust and then run and pick it back up so you can keep reading. However, I think she offers significant understanding of the wheels that keep everything turning in the adoption business, how Western desires create demand and unethical supply, and she explores the systematic abuse and erasure of birth mothers/parents/families.

Overall, this is a great book on the exploitations and abuses of the adoption industry from a journalistic perspective. I think she offers a balanced view of a complex issue and tries hard to accurately capture the intent of organizations and individuals. In particular, I think she fairly observes the strengths and weaknesses of the evangelical church in relation to their actions and beliefs surrounding adoption. Joyce also provides her own very solid insights. She has a particular point to make and I think she is quite successful in doing so. The book was well researched, well written, and very much needed. Highly recommended! -

This was a fascinating book about adoption, but an aspect of it I knew nothing about - that in very recent years evangelical Christians have massively embraced adoption as part of their mission. Churches are encouraging members to adopt, but the adopting parents (and probably the pastors themselves) are not aware of the difficult ethical issues around adoption. Many of the "orphans" have family members, sometimes even parents, alive. Often the issue is poverty and/or difficulty reuniting children with family in war-torn areas. I do know of several Christian groups that have begun debating some of the questions around adoption, but I did not know how strong the other side is. Adoption sounds like a good, and my guess is that most people trying to adopt are only intending to improve the situation for these children. (I assume that the one family that used their adopted children basically like servants are the exception to the rule.)

Every family considering adoption, whether Christian or not, should read this book. The more we all know about the issues, the better we will be able to monitor adoptions so that only those children who truly need a home will be adopted.

I would have liked more discussion on WHY adoption has become so important and rose so quickly in certain churches. Even after reading the book, I didn't get a sense of this. Obviously, money has a hand in this, but I don't believe that is the major reason. I also would have liked more exploration of how the adoptive families cope with the information that their adoptions may not have been on the up-and-up now that there is little they can do to reverse it. I know many families that have adopted from pretty much every country that was outlined in the book. Most felt they did due diligence at the time and some even met the biological families at the time of adoption, but, according to this book, there still might have been misunderstandings about the process with the bio families. How do adoptive parents deal with this emotionally while still being the parents their children now need? How do they work for improving the adoption process without their children feeling as though their adoption was a mistake. -

Content Warnings: All the.

This book made me scream "What the fuck" at my screen many, many times. I can't fathom how Kathryn Joyce managed to compile this book without going insane or smacking someone. Hats off to her.

The attitudes of evangelical christians and other fundamentalist whackjobs are truly mind-boggling. Even though there were a few voices of sane people among them included in the book, the very fact that so many children were trafficked and abused, treated like slaves and some even murdered, by people largely of those communities makes me honestly doubt their fitness to be parents of any kind.

The fact that the Allisons and Campbells and other families mentioned in this book have not been sentenced to life in prison is despicable. Not to mention this one woman who serious-fucking-ly said that she would have *murdered* her adopted daughter if she had not rehomed her, and that "by God's Grace" she did not murder her. Like what the actual fuckwaffles, how is this person allowed to walk free in society and raise children?

All of those people, the Allisons, the Campbells, the Pearls and the rest of them - truly, I hope that hell exists, for they deserve to be there.

The subject matter is heavy, so I can't recommend the book as a light read or when you're feeling down. Understandably, Joyce quotes many people she mentions throughout, and some of the stuff said by ultra-fundamentalist adopters (especially of Liberian children) is of such extreme and obvious racism that it was hard to stomach.

It's an amazing read that will stay with me for a long time. But damn it, I wish it was fiction. -

Adoption is a business. And like many businesses, there's the positive, polished public persona- and then there's the truth.

I've been skeptical of the merits of international adoption for a while. There's good reason to feel "off" about international adoption- it's criminally flawed. And yet we've allowed feel-good stories to dominate how we think and talk about adoption of all kinds. Those stories are wrong. The abuses and corruption that occur in international adoptions are rampant and tragic; it's a system that is failing birth parents, adoptive parents, and children with truly horrific outcomes.

Domestic adoption is surprisingly uncommon; very few infants are surrendered by their parents each year. I am a vocal proponent of birth control access and abortion access; the ideal way to deal with unplanned pregnancies is to prevent them in the first place. When they do occur, parents who want to parent should be helped to do so; instead many young women are treated as though they are not entitled to their own children simply because other childless families may want them more. This is absurd and hurts women- Joyce cites a study that alleges women who relinquish children to adoption have more intense feelings of grief and PTSD than women whose children have died. Finances should not hold women and men back from becoming parents; it is not a godsend if you become a parent because someone else was too poor to make it work.

Virtually every page in this book horrified me in some new way. I was furious and heartbroken in turn. I never want to pick it up again, but I hope I remember every injustice contained within because these are stories and lessons we can't forget.

Readers who enjoyed this book would find "The Girls Who Went Away" (cited by Joyce) to be a natural predecessor to The Child Catchers. -

I found this book revelatory. I came into this book wanting to be more informed about what unethical and abusive practices to look out for in the adoption industry so I could warn friends and be aware if at some point in my life I decide to adopt. I'm about halfway through, and so far what I'm getting out of it is threefold:

1) Shock that what I had been told growing up in the church was simply lies. There is no shortage of adopted parents for young children, quite the opposite. Adoption is not an alternative to abortion (regardless of whether you see abortion as a medical procedure or a tragedy). There is no orphan crisis. There is a need for people to take care of older children - that's what foster care is for - but even for older children international adoption is often founded on lies.

2) Rage. Rage at the racism and colonial mindset that lets supposedly Christian organizations think that lying, shaming, and using legal clout to take children from their parents. It makes me want to scream the statistics in this book from the rooftops, or at least Tumblr.

3) Liberation. This is more of a personal one, but as a queer man I also internalized somewhere along the line that it would be selfish and wrong to create new children (whether the old fashioned way or through surrogacy) because there were so many out there that needed care. The fact that isn't true is liberating - it means that if in a few years my partner(s) and I decide to parent children, we can choose how to do it. But, uh, I'm pretty sure I won't choose adoption. This book has convinced me of that. -

If you want one book that explains much of what's frighteningly wrong in the connection between evangelical Christians and adoption, this is it. Tight research, well delivered; nauseating realities.

Highly recommended for anyone interested in: adoption as a profit-based industry, corruption, child trafficking, marketing, hypocrisy, modern day slavery, and the perversion of scripture to justify child abuse. -

An excellent and overdue account of how evangelical demand for adoptions is sharping the global adoption industry. Very worth the read. More detailed review to come.

-

Anyone involved in adoption, or involved in adoption policy, should read this.

-

An eye-opening account of how evangelical christians have come to dominate the international child trafficking business, aka International Adoption. I was utterly appalled at how flippant these people are when it comes to the best interest of children. If only they could be more Christ-like & walk a mile in the shoes of these children. But why would they? They have ALWAYS thought they are better than everyone--rules & laws aren't for them; they are above such trivial conventions. Somehow though, if there were people who wanted to take their kids to live in Guatemala or Haiti or Ethiopia or Liberia or South Korea--never to be seen or heard from again--they would move heaven & earth to stop the stealing of such children. Better yet, if they want to adopt a child from another country, they should be required to live in said country until the child is 18; this way, they would know what it is like to give up everything they have ever known & try to adapt to customs & languages & other day-to-day activities they know nothing about. Stop treating these kids as trophies & start treating them as human beings!

PS: I knocked off a star because the book was poorly organized. There's nothing worse they having to slog through chapters that are far too long.