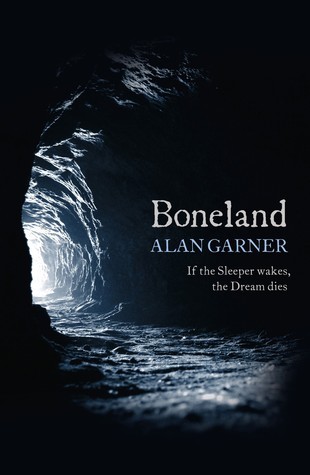

| Title | : | Boneland (Tales of Alderley, #3) |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Kindle Edition |

| Number of Pages | : | 165 |

| Publication | : | First published August 30, 2012 |

A woman was reading a book to a child on her knee.

“‘So the little boy went into the wood, and he met a witch. And the witch said, “You come home with me and I’ll give you a good dinner.”’ Now you wouldn’t go home with a witch, would you?”

Colin stood. “Young man. Do not go into the witch’s house. Do not. And whatever you do, do not go upstairs. You must not go upstairs. Do not go! You are not to go!”

Professor Colin Whisterfield spends his days at Jodrell Bank, using the radio telescope to look for his lost sister in the Pleiades. At night, he is on Alderley Edge, watching.

At the same time, and in another time, the Watcher cuts the rock and blows bulls on the stone with his blood, and dances, to keep the sky above the earth and the stars flying.

Colin can’t remember; and he remembers too much. Before the age of thirteen is a blank. After that he recalls everything: where he was, what he was doing, in every minute of every hour of every day. Everything he has read and seen.

And then, finally, a new force enters his life, a therapist who might be able to unlock what happened to him when he was twelve, what happened to his sister.

But Colin will have to remember quickly, to find his sister. And the Watcher will have to find the Woman. Otherwise the skies will fall, and there will be only winter, wanderers and moon…

Boneland (Tales of Alderley, #3) Reviews

-

Over 50 years ago Alan Garner wrote The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and its sequel, The Moon of Gomrath, two books of magic and myth, featuring the children Colin and Susan. They encounter a wizard who guards sleepers beneath the hills – Arthur and his knights, perhaps – sleepers who will wake to save us in our time of greatest need. The children encounter elves and dwarfs, goblins and killer cats, battle the evil shape-shifting Morrigan, and make their way through a patchwork of mythic events and battles, culminating, at the end of The Moon of Gomrath, with a Herne-like Hunter and his men riding their horses to meet the nine sisters of the Pleiades, leaving Susan, who needed to be with them, behind, wanting to go the stars, and Colin only to watch.

(There are well-drawn characters in those books, but they are not Colin or Susan. And the landscape of Alderley Edge is the strongest character.)

Garner continued creating mythic fantasy out of the matter of Britain, building, reimagining and recreating tales from the Mabinogion and from a hundred other sources, and then he began writing novels intended for adults, stories hewn and chipped from the past. (The past is always with us in Garner. The stones have stories.)

There was to be a third novel of Colin and Susan, but for fifty years Garner did not write it.

In Boneland, he also does not write it, although he describes it, implies it, tells us its shape. Instead he gives us, what? A fourth book? A coda? Either way, it is an adult novel about loss and history and memory and mind, a link between the present and prehistory, a place where everything Garner has made before comes together.

Colin has grown up to be a brilliant, but extremely troubled, astrophysicist. Susan is not there. Colin is autistic, has problems with memory (he remembers everything after the age of 13, nothing before), cannot relate to other humans, is searching the sky for intelligent life, and hunting for his sister in the stars. As the book begins he is being released from a hospital after some kind of breakdown.

Boneland is a realistic novel of landscape, inner and outer, past and present. It becomes a novel of the fantastic toward the end: perhaps old magics have risen to show Colin the way out, perhaps he has conjured them himself as he confronts his demons and his pain. I do not know if the conclusion of this book makes sense if you have not read the first two books, and I am not entirely certain whether reading the first two books will make it easier to read this one. Boneland demands a lot of the reader, either way. But it returns more than it demands.

The characters are well drawn – Meg, the too-good-to-be-true therapist and Bert, the salt of the earth taxi driver, linger in the memory long after the book is done. The Watcher, who provides the novels alternate point of view, gazing out from the caves of prehistory, gives us an affecting and powerful look at a mind ten thousand years away, and a way of looking at the world that is not ours, or Colin's. As the Watcher story intersects with Colin's story, the Weirdstone novels also conclude (although they conclude in negative space, as if we are seeing the after effects of events in a book unwritten) and Colin's story concludes with them.

Trying to express how and why Alan Garner is important is difficult. He does not write easy books. His children's books were powerful and popular, but never easy or comforting; his adult novels are lonely explorations of present and past. He is a master of taking the material of history, whether myths and stories or landscapes and artifacts, and building tales around them that feel, always, ultimately, right – as if, yes, this was how things were, this is how things are. He is a matter-of-fact fantasist, who builds his fantasies solid and real. Boneland feels like the book you write when you can no longer muster the belief in magic to write about elves and wizards in caves, but you can write about the older magics, the flint-knapping workings of ancient times, and you can believe in the power of the mind, and the crags and caves and outcrops, you can believe in the landscape, because the landscape is always there. And you can still believe in sleepers under hills, believe in the legend of the wizard buying a horse that began The Weirdstone of Brisingaman.

The words Garner chooses, carves, inserts into his prose are perfect. He deploys short, accurate words better than anyone else writing in English today, and he makes it look simple.

Boneland is the strangest, but also the strongest, of Alan Garner's books. It feels like a capstone to a career that has taken him, as a writer, to remarkable places, and returned him to the same place he started, to the landscape of Alderley Edge and to the sleepers under the hill. -

I often see disparaging reviews (many of them of my own books) begin with 'I wanted to like this', it combines both a sense of personal disappointment in the author along with the double put-down of 'even with a following wind I couldn't like this'.

I wanted to like this book more than I did. This is more by way of personal disappointment in me rather than in Alan Garner. I see Neil Gaiman laud it and damnation I want to be as cool as he is and 'get' this book. I count myself as fairly literary, I love powerful, sparse, poetic prose. I'm not scared of literary or philosophical themes, and like the protagonist in this work I have one foot very firmly in science with the other sliding about in imagination/storytelling/arts/philosophy. On top of all that - I am (or at least was the last time I read them many years ago) a huge fan of the first two books in this trilogy. I've cited Garner as a strong early influence on my writing/the landscape of my imagination.

I went into the book forewarned that this volume was orthogonal to the first two in both style and content. Fifty years stand between the writing of The Moon of Gomrath and Boneland. I don't for a moment think that this book was lightly undertaken or that it isn't underwritten by both profound thought and deep personal significance.

There are passages of considerable power in the book, lines with a spare beauty about them.

_However_ despite all that ... for me the whole thing failed to gell. Much of it felt confused and repetitive. The reason for that no doubt lies in the fact that Garner is trying to put us in the mind of a confused genius struggling with mental health issues and (possibly) in the mind of a long dead man defined by a prehistoric mindset and struggling with a lost mythology.

The thing is ... that it really did read as confused and repetitive. The description was so sparse as to leave me with little to hang on to. I understand that this isn't meant to be an easy book and that it's not intending to give me a riveting story, likeable characters to follow, excitement etc, nor is it going to hold my hand as it runs through its strange landscapes. But ... dammit ... I've been moved/enthralled/intrigued by books like that before ... and this one ... just didn't take me there.

I would love to wax lyrical about the power and genius of Alan Garner. I would love to pat myself on the back for being able to tune into his wavelength and take from this difficult book some sense of awe and wonder, some collection of existential questions that if not answered were at least posed in a way that set me orbiting them.

I just can't.

I hope it works for you.

I found enough beauty and intrigue in it for 3*. 2* would be too harsh. 4* would be a lie.

I do feel as though I failed in reading this book rather than Garner failed in writing it.

[as a side note - the scientist part of this was largely unconvincing to me (as a scientist). I can tell myself that Colin's repeated delivery of constants/durations/distances to a great number of decimal places was to illustrate his Asperger's syndrome rather than his credentials as a scientist (precision in such things not being an important part of scientific discussion), but the whole telescope element was weak. Colin is pointing this very valuable resource at the Pleiades "looking for his sister". I can buy into his logic of belief, non-linear time etc as meaning he hopes for some insight from the study - but the feeling is that 1930s cigar smoking scientists are just having a play and trusting a 'good fellow' to be doing good work. Of course the reality is that he would be working on a project, that project would have been based on a proposal approved by a panel - and so whatever his ulterior motive, people working with him would have a reason for his study and what it hoped to achieve scientifically. There is no hint of this at all in the book and it makes even the 'real' parts of the work seem unreal (to me)]

Join my Patreon

Join my 3-emails-a-year mailing list #prizes

..... -

This is a strange book - which came as no surprise, as Garner's novels have been going from strange to stranger since

The Owl Service. Here we have a third volume of a childrens' fantasy sequence (

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and

The Moon of Gomrath) - but this is most definitely not aimed at the traditional childrens' market - it's squarely aimed at adult readers, perhaps the readers who read Garner's most famous works as kids, like me, and somehow or another turned into adults in the mean time. So that's pretty odd - I can't think of another trilogy where that happens! But that's just the start of the weirdness.

The book alternates narrative passages and dream sequences. I've read numerous novels with occasional dream sequences and heard of a few that are entirely dreams and read one or two dream-vision poems but I can think of no other novel where dreams occupy such a high proportion of the text without being a dream throughout. So that's unusual, too - but the dreams themselves are strange. Well, all dreams are strange when examined in the cold light of morning, having woken, right? But these are even stranger - they read like Shamanistic spirit journeys - which were generally induced hallucinations. And hallucinations and dreams aren't really the same thing. Then there's the ending. Garner endings have been getting progressively more bonkers, cryptic and inscrutable since

Red Shift. This one is somewhat different from those but no less shocking and baffling, though many things are also made clear. There are some clues that something even more weird than the obvious weirdness is going on - enough foreshadowing if you are paying attention to make it clear that Garner knew what he was doing from the outset - which is no surprise. Garner is a very intelligent writer and he is discussing something interesting here, about truth and story and science and myth and magic.

The story is a little difficult to get into - it took me about 40p - because initially there's no discernible plot and the dream sequences are surreal and a little difficult whilst occupying a higher proportion of the text earlier on - so it's necessary to persevere a bit if you want to find out what happened to Colin after the Moon of Gomrath has passed. But I strongly recommend you do, if you ever liked a Garner story when you were a child. -

Flagged as the third in the Weirdstone trilogy and published 50 years after the first two extremely popular stories were written, this book came as a shattering disappointment to this loyal childhood devotee of Alan Garner.

His renowned fantasies, aimed at ages, say, 10 to 13, and kind of a cross between Enid Blyton and Tolkien, were the must-read volumes among my young peers in the 70s. They were imaginative, original, fast-paced and utterly gripping and followed the adventures of Colin and Susan, siblings billeted with an elderly bucolic couple in the northwest UK town of Alderley, after a small precious stone around Susan's neck, given to her mother by their current hostess and then passed on to Susan, becomes the target of assorted warring ancient wizards, witches, dwarves, elves and goblins who live hidden in the cave-system beneath the mediaeval copper mines of the region. Without the stone's supernatural protection, 400 sleeping knights and their steeds who, according to an ancient prophecy, will awaken to defend the world against ultimate destruction, will fall vulnerable to evil magic. Inspired by a devotion to Celtic myth and laced with a subtext of regret at the post-industrial erosion of nature and our faith in the mystical, the books were filled with poeticism and suspense. While the first (The Weirdstone of Brisingamen) focused more on Colin's part in saving the stone, the second (The Moon of Gomrath) entered Susan's mind as she was compelled in a more feminine universe to protect a bracelet entrusted to her by The Lady of the Lake. Garner's skilful interweaving of the ancient and modern gave the stories an exciting reality in his young readers' eager minds.

So expectations bloomed high when I happened upon this recently published sequel. With our world now facing possible permanent devastation from climate change, would the four hundred at last stir from their slumber to restore the power of good over evil? Surely we must be on the threshhold of the universal destruction to which the legend referred? What did the wisdom of the ages have to impart to the 21st century, and by what adventures? I opened Boneland's covers as hungrily as the child I once was.

From the first page I felt let down. We find Colin, who must now be in his early sixties, now insane, with no memory of his life before the age of twelve. Susan is out of the picture altogether (though an increasingly desperate hope for her return ended up being for me the only reason to keep turning the pages). The bulk of the prose is written in ambiguous riddles detailing the internal conflicts in super-intelligent Colin's mind as he is allowed to hold his job as an astronomer while attending sessions full of arch TV dialogue with a sympathetic female psychiatrist. At first, like him, you think she's a new embodiment of the super-villainess witch from the first two books, but no such luck. There's not a skerrick of magic in this story. It's one of the dullest, most pretentious tracts I've ever forced myself to read.

In the Weirdstone of Brisingamen there's a memorable chapter recounting the painful negotiation of a narrow skein of deep subterranean cracks in total darkness as the characters' only escape from certain death, with no knowledge of what lies ahead, one section of which is a completely underwater tunnel of unknown breadth, height or length. The constraints of this rock prison force them to bend backwards, turn upside down, pin their arms at their sides for unforeseeable periods, and get through blind, tiny gaps only by severe anatomical contortion. The claustrophobia was so palpable that it had me physically squirming in my seat even a month ago as I reread the book. It seems the intervening half century has channelled Alan Garner away from the thrill of adventure and towards the nightmarishly oppressive, which, in such palatably small doses, he evoked so well. When it lasts for a whole book on adult terms, it's torture.

That said, he's still a special artist in the medium of the English language. When a description of his strikes true, exhilaration sparks, and there are a few such moments here. But the whole wintry book is deliberately obtuse, and its relationship with the world of its predecessors is ugly and post mortem. The language used to delineate the tedious and hard-to-follow internal conflicts Colin hopes to resolve never transitions out of riddles, and the author's misguided attempt at catharrsis fails miserably, because he is not in touch with the reader. His preoccupations are admirable: a desire to understand and revive the ancient mind, and perhaps to lament the loss of imagination that comes with conventional western adulthood, but he communicates nothing but frustration and despair. Against what one imagines must have been all his intentions, all he succeeds in doing is infecting his reader with the very evisceration of faith that he bemoans: he kills our faith in himself, as both a storyteller and mentor. While he seems to revisit the locations of the previous stories (it's very hard to tell) only one truly discernible vestige of the original story remains -- which must be gleaned from a deliberately and unnecessarily cryptic telling -- and that's the reason Colin has lost his marbles and his memory. Nothing interesting develops from the revelation however. The author may dispute this, but Colin never reconnects with the magic that, in the universe of the first two volumes, was once so real. So actual. So objective. In refusing to allow that it still is, by effectively denying it ever existed, by declaring it lost, Alan Garner has all but betrayed his once so dedicated readership.

If you feel that this review is underscored with anger, you're right. What a missed opportunity! Boneland is boring. So boring, when it could have been so exciting and inspirational. Let the memories stay golden, and don't go anywhere near it. -

This is a first review, on first reading of a book I will read again and again for the rest of my life, and each time it will be different; deeper.

At one level, this is the sequel, fifty years on, to The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath. For those of us who came to them young, these books shaped our lives; the tales of two children, who meet the Sleepers beneath the hill, who fly with the Wild Hunt, who battle the Morrigan (I was terrified of the small black pony with the red eyes, as a child) were the benchmark of a childhood's dream.

Alan Garner wrote those when he was twenty one, but he was not the same twenty one as the rest of us. If you've read his book of essays, 'The Voice that Thunders' (and if you haven't, I suggest you do), you'll know that this was a boy who lay abed with childhood illnesses and learned to send himself out 'into the ceiling' where he was safe. in the ceiling, time was malleable and his to shape; he could make a day into a minute, or a minute into twenty years. He went there to survive. And he did, but he 'died' three times: which for those of you who know anything at all about where we came from, is the making of a shaman.

So this boy lived, who had died three times, came from family of makers, who occupied their minds in different ways, his grandfather memorised the London Omnibus timetable, despite being in Cheshire; he sent for the news ones each quarter and memorised them, because he could. Young Alan read (and learned) the Children's Encylopaedia on much the same basis, having taught himself to read with the back page of the Knockout comic in a hospital bed. He learned the archaeology and folklore of the Edge in Cheshire where he lived. He learned history and genealogy and mythology and physiology and anatomy and how to make a stone hand axe. He went on to read Classics at Oxford, the first generation of his family to go to university. Soon after leaving, he wrote Wierdstone, and Moon of Gomrath, and captured a whole generation of children. Later, he wrote The Owl Service, Strandloper, Thursbitch, The Stone Song Quartet: some of the greatest writing in the English language.

All of which is background to a book that is 149 pages of sheer poetry. More than that, it is dreaming. Those of you who want to know about shamanic dreaming, who haven't learned it from the Boudica books and find the few unthreatening pages on my blog insufficient - this, this, is undiluted dreaming. (not dreaming. There's a difference and it lies in the power).

Colin is an adult, and has lost his sister. That part of the book is written in the present day. It touches on the Singularity, and who we might become on its other side. It touches on time and its linearity (or otherwise: remember, this is a man who knows how to expand and contract time, if not obviously how to step outside it - except that he must have learned that in order to write this). It touches on physics, and archaeology and ornithology and folk lore. As several reviewers have noted, it is a Grail Quest, but it gives its own answer, and in any case, it is so, so, so much more than that.

The other half of the book, the part that makes it historical if you need some history in your books, is set in the pre-hominid, pre-ice age half a million years ago in which the Dreamer must dance and sing the dream of a woman into being in order that they can make a child, to dance the beasts into being, to grow the World.

This part is sheer, unadulterated shamanic dreaming. But what's so very special is the way that it links to the present. I leave that for you to find out, but what I am waiting to discover, having read it only once, is whether the dance behind the dream is happening, and the world is changing in the way it treads. -

Growing up is weird, and can seem quite sad, especially when you remember the things that used to ring and resonate and you can almost remember what the ring and the resonance sounded like but not why it set your nerves on fire and filled your head with light. I suppose they were simple things in their way. Magic. Adventure. Heroes. Villains. Whether it's age or the world, such things don't quite hold the thrill they used to, or the thrill seems cheapened by camp and over-saturation and the acute knowledge of how dreary reality can be.

But maybe it's not supposed to be quite like that. We assume as we grow that we put magic aside and sigh and set our shoulders and stride in the grey light of adulthood, and that fantasy and adventure and romance are now cheap escape routes from the grey. But there is more than one sort of knowledge, isn't there? As we grow, we acquire the tools we need to live. Language. Skills. Strength. Learning. perhaps within those tools are deeper, more profound consolations and magics.

Alan Garner wrote two children's novels: The Weirdstone Of Brisingamen and The Moon Of Gomrath. They were wildly popular, and I know I wore my copies out with rereading. They were an odd mix; old-fashioned, inventive but somewhat conventional children's stories imbued with deeper, darker roots into folklore and landscape. The adventure narrative dominated, though, and they were quite thrilling and exciting reads, for all the slight tingle of unease they left when completed. The conventional narrative was to shrink and the unease to grow through Garner's subsequent novels: Elidor and The Owl Service, until with Red Shift he broke with linear narrative completely and jumbled time and place and memory and history and myth and wove them into an extraordinary, disorienting form.

Garner does not seem to have retained much fondness for Weirdstone or Gomrath, and has a tendency to disparage them. It was a surprise, therefore, to discover that they were the first two volumes of a trilogy, and he was finally, decades later, going to complete it.

Boneland is not an adventure narrative of heroes and magic. Boneland is, if anything, almost an apology for those first two books, addressed to the landscape they exploited, the myths, the people the community and the history they, perhaps, cheapened. It is an author coming to terms with his own beginnings, both as a person as an author. And it is an offering to the reader, hopefully the reader who grew up with those two books, of a reading experience that is at once harsher, more difficult, less fantastical, much more uneasy and ambiguous, and yet also deeper, richer, broader, invoking the lost memories of deep time and the unfathomable vastness of the entire universe, while reaffirming the debt, the ties and the need for a deep rooting in a a home place.

In Boneland, Colin cannot leave Alderley Edge, cannot spend a night out of its sight or else it will vanish and the world will end. The wisdom of this book is that this is both something true and a metaphor for something else, and though we use different tools to examine the truth and the metaphor, they do not have to be divided. And so Garner offers his readers, who thrilled as children to magic and adventure, a conception of the adult world that encompasses its dreariness and a form of magic and adventure that cannot be cheapened or made camp. -

So disappointing. Can't really even begin to say anything other than - if you like the first two books, don't bother reading this one.

-

A million years ago!

-

3,25*

Interesting.

Although this is a short little book, there are so many big ideas and themes that my poor brain is reeling. The overwhelming feeling, for me, is one of sadness. Sadness and loss. It is going to take me a little while to get my thoughts in order about this book as I think a lot of it may have gone over my head. My initial reaction is, it deserves a reread,but I cannot face the sadness I currently feel to think of doing that anytime soon.

One to ponder over. -

I'm giving this a two star rating because I really don't know if I would recommend it to a friend - especially not a fan of The Weirdstone of Brisingaman, for which this is the putative conclusion in the trilogy.

Ursula Le Guin made a valiant attempt at

making sense of the book. In it, we swim between the tortured mental existence of Colin (the Valiumally calm protagonist of The W of B, now an adult, ornithologist, star-studier, owner of multiple degrees and giant pain in the ass), who cannot recall anything before his 13th birthday, and an ancient shaman figure in the Cheshire landscape, tending the Edge and ensuring through his devotions that the world goes on turning. Colin is linked, atavistically, to this figure, though his devotions take place through study and giant telescopes.

Honestly, I found the book to be an often very beautiful arrangement of WTF. The relationship between Colin and Meg (either a psychoanalyst or Bitch-Goddess, depending what light you shine on her) was gloriously described (and I wondered if 'Meg' was a nod to Meg Murray). Meg's dialogue crackles - commonsensical, utterly accepting of everything, cheer-up-sonny-boy-and-embrace-the-psychosis. "Hold the pain", she keeps encouraging him, as he flails and fights against whatever rupture happened in his 13th year, "Squeeze the pain."

Like The W of B though, the real beauty of the book is in the descriptive passages of an incredibly detailed humanised landscape. Colin the savant's bike ride to work:He reached the main road and without looking right or left or touching the brakes went straight from Artists Lane to Welsh Row. He coasted past Nut Tree and New House as far as Gatley Green until he came to the bypass and the railway bridge and had to pedal, after two point seven eight four three kilometres of free energy; approximately. The it was Soss Moss, Chelford and Dingle Bank, to the telescope.

-

I was utterly disappointed with this. It's supposed to be a sequel to two of the greatest books of my childhood; books full of magic and adventure and wonder. This was mostly dialogue between an unhinged genius and his psychiatrist. The book centres around a now grown up Colin who remembers the barest fragments of the events of the first two books and looks for his vaguely remembered sister (Susan) in the stars. What he mostly seems to do, though, is shout at his psychiatrist for asking questions he doesn't want to answer. The ending didn't really resolve anything for me; I've seen a lot of reviews saying they 'didn't get it', and possibly there was something I didn't get because this didn't conclude anything for me. I gleaned that Colin tried to wake the Sleepers to find his sister just after the events of the Moon of Gomrath, and that Caladin was pissed about it and cursed him to forget and remember. There was also a parallel story, a la Red Shift, of a prehistoric shaman, possibly Lower Palaeolithic....anyway. The whole thing is rambling and doesn't seem to go anywhere. It is mostly Colin trying, or trying not, to remember. Lovers of the first two books will be very disappointed.

-

Oct 2012 - I read this book in three days flat and am still processing it. It is everything that I love: place, myth, the interconnectedness of things, growing up. At one point Colin says, "it's not so much deep space that concerns me as deep place" and that seems as good enough a description of this book as any.

May 2013 - I just re-read this book and part of me wants to turn back to the start and begin all over again. It is heartbreaking, it's scary, it's funny and rich and truthful. There is so much packed into it - so many strands to follow. After reading Simon Armitage's translation of Gawain and the Green Knight (with facing original text) I found so many more allusions than I had seen the first time round - whole phrases lifted from it (pearl to a white pea, the description of hills with hats of mist, "I'm the governor of this gang") or ideas taken from it (Colin's scar on his neck that he associates with shame, his green and gold hood, the order of animals the prehistoric man hunts (deer then boar then fox), Meg lopping holly). I can't explain what this book is to me - it feels real - it is a true story. -

CAREFUL: THIS REVIEW CONTAINS SPOILERS.

Boneland is essentially the story of the psychoanalysis of Colin, the male co-protagonist of The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath -- now an adult of indeterminate middle age, working as a radio astronomer at Jodrell Bank and living in a shack at Alderley Edge. Beyond a few significant flashbacks he has no memory of his childhood adventures, but he retains the trauma of them, especially the disappearance of his twin sister Susan.

Boneland takes place in the same landscape as the earlier Alderley books, but it is no longer the haunt of elves, dwarves and wizards. This book's fantastical elements arise more subtly from Susan's implicit fate (only foreshadowed in The Moon of Gomrath, although Colin's reading of the outcome is convincing in the light of what we saw there), and what emerges as the unusual nature of his analyst. There's also a series of time-hopping reversions to the prehistoric life of a man who turns out to be a Homo erectus shaman also inhabiting Cheshire, seeking a successor to his post of observing and thus maintaining the world, whose relation to the main narrative is definite but elusive.

Though of no great length, Boneland is a dense, slippery text which starts off close to incomprehensible but becomes crystal clear as one learns to inhabit the storytelling. That's the kind of reading experience I always find rewarding, but it's not the light read its predecessors were.

In fact, it reminded me of nothing so much as the revisionist texts which reinterpret much-loved works of children's fantasy through a filter of adult understanding and knowledge: Lev Grossman's Magicians sequence and Neil Gaiman's "The Problem of Susan" (both dealing with the Narnia books) spring most readily to mind, but one could also cite Alan Moore's Lost Girls (Alice, Peter Pan, Oz) or Geoff Ryman's Was (Oz).

In most such stories, adventures are re-examined as traumatic, paradigm-shaking experiences which can neither be revisited nor fully shared, but which will colour the rest of the adventurer's life; child protagonists are followed into their problematic adulthood, with the psychological fallout of their pasts unflinchingly surveyed; and parental figures, even God-analogues, are interrogated and found wanting in benevolence and responsibility.

Boneland is exactly that kind of revisitation of past innocence with a cynical half-century of hindsight -- indeed, the Alderly books are of essentially the same vintage as the Narnia books, with less than half a decade separating Weirdstone (1960) from The Last Battle (1956). However, Boneland has the unique qualification that it's not a piece of sophisticated fanfic based around the Alderley books, but the authentic work of their original author. If CS Lewis had survived until 2008 and suddenly written an eighth Narnia book at the age of 110, it would have been comparable.

The original books are essential reading for fully understanding Garner's own Problem of Susan (although there's one non-revelation which might have been more effective if read in isolation from them). The primary source of Colin's trauma particularly makes no sense without such background knowledge: suffice it to say that what Colin thinks of as a curse may be, given its source, the nearest thing available to a blessing. The narrative is rife with this kind of unresolved moral inversion, however, and in the end the subjective ambiguity of Colin's childhood experiences grows to dominate the book.

Although I loved the Alderley books as a child, I'm ashamed to say that I've not actually read Alan Garner's other adult novels, nor even his other children's novels, Elidor, The Owl Service and Red Shift. My parents told me at the age of 10ish that they'd be too difficult for me, and I somehow never caught up with them later in life. I intend to rectify this soon. -

I loved Alan Garner's books as a teenager. And I'd still say that Elidor and The Owl Service are the best Young Adult fantasy books ever written for the younger and older ends of that spectrum respectively. I was also quite fond of his first two books, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and its sequel The Moon of Gomrath. They were also gripping fantasy adventures, and I loved the setting of Alderly Edge, which I knew quite well. Even at the time, though, I had slight reservations about them. So it was with some interest that I got a copy of Boneland, described as 'the concluding volume in the Weirdstone trilogy.'

My issues with the originals, which feature a circa 12 year old pair of twins hurled into a Cheshire setting with supernatural goings-on, were two-fold. I was already a huge Lord of the Rings fan and I couldn't help feeling that the svarts that the children discover down the copper mines are extremely derivative of the orcs in the Moria scene in LotR. I also felt that Garner flung in every tradition he could think of in a messy mix. So we had witches, King Arthur and his knights sleeping under the hill to rescue England at its peril, a wizard, the Wild Hunt and even a chunk of Norse mythology.

So what of the 'sequel'? First the good news. Boneland is an interesting book in its own right, I love the way Garner weaves in Jodrell Bank (visible from his house), and the character Meg is superb. Colin, one of the twins from the original books, now middle-aged, is less appealing (and, I'm sorry, but Garner got his surname wrong. It just sounds wrong.) But the claims on the cover are downright fibs.

Not only is there no way this is the concluding book of a trilogy - it has no similarity of feel to the first books - Philip Pullman's comments on the rear are highly misleading. He calls it a resolution of the stories of the first two books, and says those who were young when they came out (as he and I both were) 'won't be disappointed: this was worth waiting for.' Actually I was hugely disappointed. The first books didn't need a resolution: the apparent cliff-hanger that links them and Boneland isn't in the original books. And this is anything but a resolution. Let me try to explain why have problems with this book.

One is inconsistency. Having said that the original books were a real mish-mash of legends and traditions, at least there was some consistency of having a medieval English feel (with a touch of Scandanavian) to them. Apart from the use of crows, there is hardly any overlap with the mystical content of this book, which is all cod-Stone age. And there is so much of that. I really had to fight myself not to skip over the huge chunks of mystical waffle to get back to Colin and Meg, because it is deliberately obscure and unsatisfying.

It didn't help for me, and I know not everyone will agree, that it was cod-Stone age. I have real problems with this particular style. I found the same experience with Michelle Paver's Wolf Brother books. The thing is, if you use an existing legend - like the Wild Hunt - you are tying into a true tradition, and that gives a story real resonance. But we have no idea what Stone age religion was like (or even if they had any: it's all supposition). So people make guesses from cave paintings. But it always feels really false and strained to me. But most of all, as already mentioned, what we find here has nothing to do with the mythos of the Weirdstone books.

So, all in all, a disappointment. Not a bad book, by any means. But it doesn't do what it says on the tin.

Review first published on brianclegg.blogspot.com and reproduced with permission -

Definitely a fitting end to a story full of realism, initially, with a double-timeline storytelling and a little too many of the "too good to be true" characters, I was a little bit worried that the stories would veer into a stereotypically milquetoast or "soft fantasy" direction and off the Edge, but I was, fortunately wrong. Not being a specialist, but trying to educate myself in European stone age (Neolithic and Mesolithic) and Bronze Age histories and archeology, this was rather a clever play on histories, so that the alternative timeline cannot really be placed with certainty, being a little bit of a "magical dream" which will die if the Sleeper wakes. I haven't noticed glaring errors, however and I can say that writing this book must have put even Garner's skills to a test. It's a solid, and realistic end to the trilogy, which neither break the magic of the first two books, nor coddles the reader.

As for criticism of science ... Well, forgive me to knock the science off the imaginary pedestal, but you know, at night, when all the cheap snacks which stand in for the dinner for an impoverished research intern are eaten, and the numbers are STILL BEING CRUNCHED, and you can't sleep because you're not tired enough to go onto the stone-hard and horribly smelly cot under the table in one the many computer room (don't sleep in the server room, if there's a fire you're gonna suffocate to death by the firefighting system and not even the cool in the summer heat is worth that ) nothing else to do in a lab, except playing Age of Empires and reading Saint Seya. And talking/inviting to random passerby to the lab? Puh-lease, like I have had the energy or time to do that? By comparison Col(in) is a saintly science figure. -

I was most curious about this novel as I grew up on The Edge. Alan Garner was required reading in our school and we all knew the little cottage, shaped like a tea caddy, where he grew up.

It was a great pleasure to revisit the landscape through an older narrator. The prose is smooth as a stream, the author holds you spellbound through the smallest details, as good writing does. I liked the idea of Colin becoming an extremely clever astronomy geek; even if the story resolution seemed weak and arbitrary, I admired the ideas Garner was playing with - time, simultaneous lives crossing in mathematics and the vast distance of the universe.

It was also a great pleasure to read the passages about Jodrell Bank telescope. This is a purely personal detail, but when I was small, that telescope stood on the horizon and I watched it obsessively. Through the character of Colin I was able to indulge in that wonder all over again.

However, I do have to take issue with a few of the geographical details. It is not actually possible to see Jodrell Bank when you stand on Castle Rock; the lie of the land doesn't allow for it. I found an obviously photoshopped picture that suggests you can.... possibly our author refreshed his memory with some research and found this. It's a detail strictly for Edge alumnae that will not bother anyone else at all. And not worth deducting a star for either; I just mention it in case anyone else spotted it too.

-

There have been suggestions that Boneland may be Alan Garner's last novel; well, we can hope it isn't so, but if it is, then what a culmination. Simultaneously drawing on, surpassing and completing the first two Alderley Tales, Boneland is a work of illumination, bringing to life the Cheshire landscape in its entirety, from stone-age ritual to the radio telescope at Jodrell Bank, and running through the narrative nothing less than the Matter of Britain. Those familiar with the tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight will find the text full of harmonies and allusions, and glimpse a way in to the heart of the narrative. Alternatively, anyone who read The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath as a child will already have many of the tools needed to mine this dreamlike, endlessly rewarding text for meaning and resonance. Wonderful; filled with wonder.

-

I hated every moment of this pretentious nonsense. Garner came close to soiling the memory of the Weirdstone.

-

I'm not quite sure how to go about reviewing Boneland, as I definitely didn't understand the meaning of it all. Or is it just that it's actually a bit incoherent (or as another reviewer said, a beautiful arrangement of WTF).

I too came to this as so many others did because I loved the Weirdstone books as a child, and wanted to know more. The first two books finish abruptly, and always seem to be saying more than they first appear. Boneland takes the double/triple meanings to a higher level.

A few spoilers ahead.

The main protagonist Colin is suffering from mental illness, an inability to relate to people and society along with genius-level intelligence. These problems appear to have manifested at the age of 13, the year Colin's twin sister Susan disappeared and the year he cannot remember anything before. In the first two books, Susan was connected to magic far more than Colin, through the gift of the Mark of Fohla from Angharad, and at the end of Gomrath is left behind by The Daughters of the Moon.

However Boneland is set in the present(early 21st Century) and is an adult book. Magic apparently has no place here. Colin seeks treatment for his mental illness and is referred to a psychiatrist (Meg). Meg and Colin start exploring his past, a place that Colin has no memory of except for flashbacks.

Colin's past experience has been so painful that he is unable to remember, unable to process what happened to him, but Meg draws much of it out of him through flashbacks. Susan disappeared one night, taking a horse and riding into Reedesmere Lake. This lake has special significance for Angharad and the Daughters of the Moon, so it would seem that she went back to join them, but left nothing for Colin or the Mossocks to say where or why.

After her disappearance Colin tried to wake the Sleepers, tried to access Cadellin's help, but was struck down by lightning (by Cadellin?) to make him forget, forget about the magic, forget about Susan, forget about the importance of the Sleepers. In this moment, his life is changed.

There is a moving and very cathartic moment at the end of the book where Colin has enough memory back to realise that it is not the Sleepers' place to find Susan and that he has an immense amount of guilt about trying to wake them.

Just as it seems that things make sense, the magical side of the book shows itself. Meg is not real. The house where Colin went for therapy is derelict (shades of the house in the Moon of Gomrath where Colin was trapped by The Morrigan?) and reference is made to Meg also having something to do with the Moon phases as did The Morrigan (old moon) and Susan (new moon).

Then of course there is the whole story about the Watcher on the Edge interspersed with Colin's story, it slowly becoming clear that someone always needs to watch over the Edge, and Colin is the current Watcher.

So what is this book about? I really don't get the full picture, but it's beautifully written, and the parts that I did grasp were moving and gripping and emotionally disturbing too. -

Why five stars for a book which is in turn challenging, worrying, baffling and often disjointed? Perhaps because of the way it made me feel when I put it down- as if I'd been afforded a glimpse of some wonderful, terrible secret, perhaps even the secret to our existence and our demise.

I had no idea what to expect when I began reading Boneland. Its predecessors were the two books that, as a child, made me to decide to become an author. Their effect upon me was instant and shattering. Garener's prose, beautiful and bleak and utter compelling, is evident again here but this- I should warn you- is not a book for children. I'm not certain who its target market is, except readers of The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and Moon of Gomrath. Regardless, I was astonished to find that Boneland is something entirely unique- I've never read anything quite like it before (even amongst Garner's other works) and I doubt I will again.

It's a fable of consciousness coming apart, of a mystical seamlessness between past and present- and ironically for a book which is often difficult and disjointed, it points to the interconnectedness of things and the constant Mystery (I believe the capital letter is deserved as some think of the inexplicable beyond our sight as a form of deity) present behind and beneath the lives that we think we lead.

In my view, because of the feeling of stupefied wonder it produced (so few books do that to me so strongly), the quiet excitement that it stirred- a little like stargazing, which if you read the book you'll see is not entirely irrelevant- it is fully deserving of five stars. You may well feel differently- but I hope not. This is a strange, unique masterpiece. -

If you come to this book looking for a direct sequel to The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath, you will be sorely disappointed. It's more of a look at the adult Colin who cannot remember his childhood and has grown into a brilliant but very troubled scientist juxtaposed with the lyrical story of a prehistoric man who sings the sun up and down around the year. And Susan? She disappeared as a child and Colin is still trying to find her...

This book has lyrical language and may be an attempt at a mystical exploration of how a man deals with suppressed memory and the conflict of fantasy with reality. It did not work for me but may for other people. I do give it two stars since I did finish the book and it will echo in my memory for some time. -

I did write "I can't rate this book yet. I've now read it twice and really need to digest this complex meditation on time, landscape and religion." I'm still not sure I can really do it justice with a review or reduce it to star rating. Probably this and allied blog posts

http://nicktomjoe.brookesblogs.net/20... are the nearest I can get to its complex and scholarly narrative. -

Well. Perhaps I didn't get it, but I'm really sad about this being the ending to two of my favourite books as a child.

-

Beginning second reading, January 13, 2020.

-

It is almost impossible to say anything about this book without spoilers, so I hope that anyone who reads this has already read the book.

It is a sequel to

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and

The Moon of Gomrath. In those books twelve-year-old Colin and Susan go to stay on a farm near Alderley Edge in Cheshire, England, and discover that the Edge is haunted by all kinds of strange creatures, malicious goblins, suspicious fairies and elves and the like, and there is a strange woman, a witch, who seems to have evil designs on them, and especially a stone that Susan had inherited.

Some of the creatures, good and evil, that they encounter are from local folklore, and others from stories from further afield. Eventually the children overcome the forces of evil, and are left in peace for a while.

Boneland is set much further in the future, where Colin has grown up and become a professor of astrophysics.

One problem that Professor Colin Whisterfield has is that though he has an exceptionally good memory, he can remember very little of his childhood before he was 13.

He works at the

Jodrell Bank radio telescope, and spends much of his time at work trying to find a twin sister that he thought he had, whom he believes has vanished into the Pleiades, riding on a horse. He has a bad conscience about wasting his employers' time on this personal project, and so at one point he resigns, but his resignation is not accepted.

He is also worried about his missing sister, whom he can hardly remember, and thinks he might be going mad, so he visits a psychotherapist, Meg, She tries to probe his memories, but there are some places in his past where he both wants to go and fears to go.

This is where the story gripped me as a reader. Having read the first two books, I wanted to know what had happened to Colin's sister Susan. In reading the earlier books I hadn't known that they were twins, and liked Susan more as a character; I thought Colin was a bit of a wimp.

But why should I care what happens to a fictional character when another fictional character is looking for her? You can't dismiss Susan as imaginary (within the story) when she's been in two books you've read before. Was Colin imagining her all along? Were the first two books just about a dream he was having, and that he couldn't remember? But then he himself is a character in a book, so why do I want to know what happened to Susan?

Colin also keeps having dreams of long ago of a primitive tribe that once lived in the place, and also of having betrayed the guardian of a secret place on Alderley Edge (this is Cadellin Silverbrow, from

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen). So Colin becomes a kind of self-appointed guardian of Alderley Edge and its history, even though tantalising gaps hide essential parts of that history from him.

Then Colin is shown a stone that was discovered on the site of the main telescope at Jodrell Bank, in a place that was geologically impossible for it to be unless someone put it there. It seems to have a personal message for him.

He shows the stone to Meg, who tells him that she has done research in the birth, marriage and death records, and can throw some light on Colin's forgotten past before he was 13. He did have a twin sister, but at Colin's insistence Meg does not mention her name. She disappeared one night with a horse belonging to the Mossop family, who were their guardians. The horse was later found on an island in Redesmere, but though divers searched and the lake was dragged, no trace of a body was found. In

The Weirdsone of Brisingamen Redesmere was where Angharad Goldenhand had fastened a magical silver bracelet around Susan's left wrist, on an island they had reached without crossing the water.

Then Meg says goodbye, and is gone. Colin can find no trace of her in the phone book, and the house where he went for his therapy sessions has been unoccupied for years. Even the taxi driver who took him there has gone. So did he ever have a sister? It was Meg who had told him about her birth certificate and the coroners report, so how could be be sure that Susan was real if Meg herself was not real?

That's a literary trope I recall only seeing once before, in

Sophie's World by [author Hostein Gaarder]

Row, row, row your boar

Gently down the stream.

Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily

Life is but a dream. -

If you're coming to this as a fan of Weirdstone and Gomrath, then be warned - while it's pitched as a conclusion to the 'trilogy', it's actually nothing like its predecessors. What it does have is one of the main characters from Weirdstone, now in middle age and struggling to come to terms with the odd and otherworldly events of his childhood. Dense, poetic and at times frustratingly obtuse, Boneland nonetheless spins a well-crafted and folklore-rich tale from its raw material of a troubled psyche, astronomy and the geological lore of the land itself. A strange, uneasy book, but rewarding reading - both for those who grew up with Weirdstone, and those who are oblivious of Garner's works for children.

-

So exciting to come across Alan Garner again! I first read his work as a teenager...or maybe as a 20=something? anyway, I loved the complexity of the mythology and the way the stories didn't really end. This book was sitting on my host's shelf in Macclesfield, which is when I learned that Garner is not Welsh (although that's nearby) but a Cheshire man. I wanted to shyly stalk him (he lives up by Jodrell Bank, which has a cameo in this book), but didn't have a car. This book is much darker and much more adult in content, even though it's the third of a series that was written for kids (with kid protagonists.) I liked the way Colin's search is enmeshed with the neolithic shaman's search, and I love the language used for the shaman: very sagalike. And I enjoyed the Cheshire accent: "Let's be having ye then." Okay, let's.

-

Uncover your past. Maybe something is hindering Colin from remembering, not just amnesia. Could it be magic, or himself? Sleeping hero.

I loved the whole series.