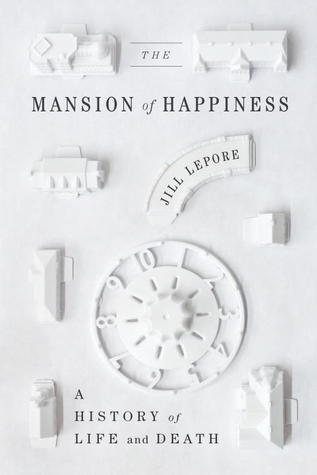

| Title | : | The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0307592995 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780307592996 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 320 |

| Publication | : | First published June 5, 2012 |

| Awards | : | Andrew Carnegie Medal Nonfiction (Shortlist) (2013) |

How does life begin? What does it mean? What happens when we die? “All anyone can do is ask,” Lepore writes. “That's why any history of ideas about life and death has to be, like this book, a history of curiosity.” Lepore starts that history with the story of a seventeenth-century Englishman who had the idea that all life begins with an egg and ends it with an American who, in the 1970s, began freezing the dead. In between, life got longer, the stages of life multiplied, and matters of life and death moved from the library to the laboratory, from the humanities to the sciences. Lately, debates about life and death have determined the course of American politics. Each of these debates has a history. Investigating the surprising origins of the stuff of everyday life—from board games to breast pumps—Lepore argues that the age of discovery, Darwin, and the Space Age turned ideas about life on earth topsy-turvy. “New worlds were found,” she writes, and “old paradises were lost.” As much a meditation on the present as an excavation of the past, The Mansion of Happiness is delightful, learned, and altogether beguiling.

The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death Reviews

-

This was a thought-provoking read. Not all of the chapters, many of which had been essays written for the New Yorker, were equally of interest to me, but the overall theme of the birth of ideas was very interesting. Things that we take for granted as givens, like the idea of adolescence as a stage of life-it's good to be reminded that those ideas had a beginning, sometimes strange ones with unlikely (and sometimes really horrible) folks promoting them. Even the people who were proponents of the most wonderful things, like children's libraries, were complicated.

Reading this book got me thinking a lot about ideas and what we take for granted. It made me wonder what people 100 years in the future, or even 50 years in the future, will think about us—our political battles, our religious beliefs, how we raise families, how we approach life and death(which is the focus of this book, although I think it would be a better description to say it's about our approaches to the stages of life).

The introduction, a short history of board games—specifically about games that mimic life: the titular Mansion of Happiness, the Game of Life, and many others—sets up the structure for the book. The chapters are a progression of life's stages and moments in history that formed pervading ideas about these stages. The Children's Room, about the origin of children's libraries and more widespread attention being shown to children's literature, was the chapter I enjoyed the most.

This book is not really 320 pages long. It's 192 pages, and the rest of the pages are mostly endnotes. I’m glad she so thoroughly documented her sources, but I wish she had done footnotes rather than endnotes. I can't see a little number at the end of a sentence and ignore it, so I did a lot of flipping back and forth.

My rating is really closer to 3.5 stars, but the book did get my brain working, and it was definitely worth my time. -

Liked it more than I'd expected (feared) as it certainly isn't dry. However, this is one case where I believe the focus is more geared towards female readers. So, mileage may vary; I can see others getting into the "story" more easily. Anyway...

Author succeeds in a narrative that covers the American experience from conception to death (and beyond), highlighting the cultural shifts since colonial times. Fans of definite linear structure ought to be truly pleased in that regard.

In terms of content, however, there's a lot of quoted source material - endnotes make up half the space! Many chapters are mini-biographies that represent the larger topic: Lillian Gilbreth (perhaps known better as the mother in the film "Cheaper by the Dozen") regarding matrimony and child-rearing, for example. One chapter at a time the way to go for this book.

Recomnended especially for fans of Mary Roach, as I found the style reminiscent of that writer.

As a postscript, I'll mention that I found the discussions of eugenics rather uncomfortable, not that she at all espouses it, but the concept does come up more than once. -

The Mansion of Happiness by Jill Lepore is a collection of loosely-connected essays exploring The Meaning of Life (capital “T”, capital “M”, capital “L”). It turns out that the answer to this grand, existential question frequently turns on the unexpected and, often, the seemingly prosaic. To wit: photography and political calculus did far, far more to create the “right to life” movement than organized religion (especially protestant Christians).

Instead of trying to answer the question of the meaning of life, Lepore looks at how modern and ever-changing forces--scientific, economic, political, technological--fundamentally alter the seemingly eternal “truths” of life. For example, there have always been children, but “childhood” is a modern construct. Where did the idea of childhood come from and what forces shaped (and continue to shape) its conception? The author uses various anecdotes and cultural artifacts--the board game “Life” and its numerous iterations, Stuart Little, 2001: A Space Odyssey, among others--to illustrate changes to the concepts of birth, childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age.

Lepore writes with a clear point of view but without an agenda, an approach and accomplishment admirable and all too rare. While I think I understand the personal and policy implications of her essays, she resists the urge to spell anything out. This is no diatribe. My assumptions about her intent could be wrong. In fact, I would argue that this space--the distance between knowledge and what that knowledge means and to what ends it is used--is an essential theme of the book. Showing how hucksters, charlatans, politicians and marketers seize, distort, obfuscate and deny science and facts is one of clearest takeaways from this book. One new-to-me example was how Planned Parenthood was hijacked away from Margaret Sanger by eugenicists sharing a philosophy of “family planning” akin to the Third Reich’s.

At this point, I feel it’s important to offer a significant disclaimer: The Mansion of Happiness draws from a very narrow and hegemonic viewpoint. It deals almost exclusively from a post-Enlightenment (really post-Industrial; the Enlightenment era content is usually provided as context for the meat of the story), white (oh-so-very white), American point-of-view. While I try not to presume authorial intent, I would say that Lepore doesn’t even attempt to present a complete picture of the forces that shape(d) our concepts of life and death. Rather, it seems she is merely presenting some of the ways transient forces change what we believe are eternal truths (“the sanctity of life” is a concept younger than many Gen-Xers). That said, I believe the author would have better served her work by explicitly explaining her choice of such a very exclusive (and possibly exclusionary) purview.

If all this sounds like a bit of a trudge--good, important (capital “I”) reading--don’t worry. Lepore writes with alacrity and a sly sense of humor. She chooses interesting stories and then lets those stories do the heavy lifting for her instead of spilling ink on ponderous and limiting (and agenda-driven) explanations/interpretations. This book is not deep--and that’s no slight. It’s an easy read that I found wholly original and thought-provoking.

The Mansion of Happiness is an entertaining and at times profound exploration of the ideas of birth, life and death. After reading it, I have no better idea as to the meaning of life, but I do have a better understanding of the meaning of “life”, i.e., a more-informed way of unpacking the language and semiotics comprising the stages of our existence here and now on earth. -

Prince Hamlet's observation that "there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so" might aptly summarize Jill Lepore's collection of wide-ranging essays on ideas about life and death. And since perhaps no country other than America has produced weirder fancies on those two phenomena, Lepore provides a hilarious and witty historical tour of same, from Milton Bradley's 1860 board game, "The Checkered Game of Life" (it didn't include Boardwalk but it did feature a game-ending space called "Suicide")to the modern craze for cryogenically freezing corpses for future (it is hoped!) resurrection. Along the way in these free-ranging essays (most of which originally appeared in the "New Yorker," Lepore touches on subjects that prove more relevant than you might suppose: the misogynist framework of Stanley Kubrick's "2001," the strange history of breast-feeding, Anne Carroll Moore's invention of the public library's "Children's Room" and her later, unsuccessful vendetta against E. B. White's "Stuart Little," the bizarre chronicle of sex education in America and the improbable evolution of our obsession with "parenting" over the last century. You may not always agree with the political sensibility that informs Lepore's writing--did I mention these essays were written for the "New Yorker"?--but you cannot fail to be informed and amused by her inexorable research and unstinting humor. Highly recommended--and you'll never feel the same about "Cheaper by the Dozen" after reading this book . . .

-

An odd book. It was not what I expected. It read like separate essays on the histories of widely disparate (though sometimes related) topics: nursing, eugenics, sex education, children's books and libraries, marital advice, parenting advice, cryogenics and Life the board game. There are others.They all touch on a "time" of life--or on ideas about those times--but so does everything, after all. That is not necessarily a criticism. I can imagine essays on a child's first experience of death, a person's loss of virginity, learning to write, work life, etc. So this is Lepore's selection of the things that interest her about human life in our culture(s). She has a wry sense of humor (at least once she let out an "ahem" on the page). My favorite was the chapter on children's books (surprise!) and the librarian who tried to prevent the publication of Stuart Little and then the purchase of it by children's librarians. The "3" is probably because I was disappointed that it wasn't more about what I expected.

-

Loads of random information that is absolutely fascinating!!!!!

-

Because the chapters of this book began life as essays in The New Yorker magazine, they are somewhat loosely strung together and feel as though they could stand on their own, should you wish to delve into an individual topic. The author, a professor of American History at Harvard, has a broad overarching theme of the changing attitudes toward the life cycle in American culture. Her skill in pulling together disparate incidents and ideas works well, so the book is consistently interesting and entertaining. In the introduction, she explains how the idea for the book's theme came from a board game, "The Game of Life" (or, as it was called in earlier incarnations, "The Mansion of Happiness"). Surely, most Americans have played this game as children. The version from my childhood had little plastic station wagons which could be filled with plastic pink and blue babies. Who knew the original was patented by Milton Bradley in 1860, or that it was based on even earlier versions! The author notes that older versions were focused on accumulating virtues and winding up in heaven. More recent versions (including the one from my baby boomer youth) were more materialistic, ending in a millionaire retirement haven. She notes that life itself was historically thought to be cyclical; but with a stronger influence from science in more modern times, it became linear, always showing progress, but without acknowledging death at the end. Each chapter, then, deals with the changes in American cultural thought about a stage of life, beginning with birth, looking at babyhood and childhood, progressing to ideas about sex and marriage. Marriage leads to thoughts about fertility, motherhood, and time management. The last chapters proceed to old age and death, or its avoidance. The author has a wonderfully wry wit, reminding me a bit of Mary Roach's science writing. This book is just a whole lot of fun, and yet, makes you think seriously about modern beliefs concerning life and death.

**For the librarians out there,don't miss chapter 3, "The Children's Room", with its extensive discussion of the development of the children's section in public libraries and of literature for children. -

Rather than a comprehensive history, Lepore tackles the different stages of life--and how America has conceptualized, fantasized, and fought over them--through anecdotal stories and engaging, offbeat characters. Much of her research and storytelling is centered around the major shifts in American attitudes and values as a result of the Progressive Era, a period (I greatly paraphrase) concerned with improving the quality of human life through the widespread adoption of science and technology into everyday life.

Favorite chapters include "The Children's Room", about the adoption of juvenile sections in libraries, and the moral decline much fretted over that would be brought about by letting young people read "fiction"; "Happiness Minutes", how Taylorism and scientific management became popular and crept from the workplace into nearly every facet of daily existence; and "Resurrection", a portrait of a handful of futurists who see cryogenics as our only chance for immortality.

On top of excellent (and, dare I say it, quirky) scholarship, Lepore writes with a wit and rhythm that the current stable of New Yorker regulars lack. Highly recommended. -

This book is a rather meandering look at various life stages viewed through a particular perspective of American culture. While several of the passages were interesting, I had to remind myself many times what the topic of the book was, because the various stories didn't really fit together. For example, the section on childhood was primarily about the development of children's libraries and literature, which didn't really address how the concept of childhood has changed in America over time. At least twice, I found myself wondering why I was reading about children's libraries--oh yeah, because this book is supposed to be about American views of life and death.

The book was okay. I don't really think I learned much about the history of life and death. It felt like this author really didn't know what she was shooting for, so she collected a bunch of random stories and visited a cryogenics site and called it a book. -

While I found this book a relatively engaging, quick read, especially for non-fiction, I agree with the other reviewers that Mansion of Happiness is meandering, and not in a good way. By the time I had finished reading the dust cover insert, introduction and first chapter, I already had the impression that I was reading essays on miscellaneous topics Jill Lepore found interesting that she then attempted to tweak to fit a theme so that they could be published in a book. Lo and behold, in the "Last Words" chapter, Lepore writes that most of the chapters of the book began as essays written for the New Yorker. Several interesting ideas about humans' evolving worldview about the stages of life and various historical events and figures are explored, but the "story" Lepore is trying to tell isn't cohesive.

-

This book feels incomplete as an argument. The chapters are divided mostly chronologically both in terms of life span and history. However, this led to my feeling that Lepore was telling a story rather than presenting an argument. That would be fine were it her mission, but the book concludes that “history is the art of making an argument by telling a story about the dead.” It was generally an interesting story. But it does not represent a cogent argument, and ultimately, that is what I wanted from it. Also, I found Lepore’s focus on individuals a bit tedious. Ultimately, their purpose appears to have been to tie the story into a neat package. But that comes at the cost of truly understanding a progression of ideas in a society, which was what the book promised. I had particular difficulty with the chapters “The Children’s Room” and “All About Erections,” which described conceptions of childhood and adolescence entirely through books and their authors’ disagreements. Each of the sections felt like an introduction, a case study that should have been used to illustrate a greater point that just never appeared. I know what’s included in “The Care and Keeping of You,” but I would have liked to see more analysis of how that content reflects cultural change. Overall, that was my biggest problem with the book: it felt like there was too much evidence and too little analysis of it or conclusions drawn from it. Lepore seemed to relish being able to proclaim that something was a great reflection of cultural change. But there was little further explanation of why. It was a very anticlimactic read. The prose itself was engaging and I did learn some interesting facts.

-

This book is a bit different from the other books of hers I’ve read. It is chock FULL of interesting quotes strung together by the author’s observations. There are so many quotes, it reminds me of way back in high school, when I was taught to write down chunks of information on index cards and use those to assemble a final research paper. Although I doubt she actually uses index cards, In my mind, I have a fanciful image of her rifling all of those cards.

The format is a chronological progression of chapters that mirrors the progression of a person’s life, starting with history regarding children and ending with death, assuming that it’s a peaceful rest at the end of old age.

The tone is very self-aware, personable, and intimate, like a friend or favorite teacher. So it’s easy to picture her working on this.

There are lots of interesting facts woven together here here. Some are odd little tidbits like the start of board games and milton bradley and others are more substantially impactful like insights about Taylorism. The guy got super rich designing an “improved” human workflow for manufacturing and railroad companies. He made a mint, and the workers got screwed

I haven’t finished reading the book. My electronic copy was yanked out of my hands on the due date, and I have to wait for it to come back again...someday. There’s a longish wait with all the people wanting to read it. -

The best way to describe what this book is about is that it is a history of hokum, quackery, crackpots charlatans and chuckleheads as framed by the stages of life and death as refracted through a board game created in 1860 called the Checkered Game of Life. We know this game more by it's 100th anniversary reworking as the game Life.

through this we are treated to essays about eugenics, forced steralizations of the mentally impaired, cryonics, the creation of the Children's Library, how the understanding of the birthing process has changed over the centuries and much more.

throughout Lepore's writing and research are superb, especially when linking individual cases with a broader topic. She is marvelously succint when brevity forces a quick yet through overview.

Eye opening reading about how quackery was once taken far too seriously and how every era has had their Aikens and how we must keep them from power and influence or pay a heavy toll. -

"Some people will always think they know how to make other people’s marriages better, and, after a while, they’ll get to cudgeling you or selling you something; the really entrepreneurial types will sell you the cudgel."

According to the jacket copy, this is "a strikingly original, ingeniously conceived, and beautifully crafted history of American ideas about life and death." No. It is actually a collection of recycled essays from The New Yorker. They're good essays, and I admire Dr. Lepore's ability to get a book publisher to pay her for them again after the magazine already paid her for them once. I'm just sick of essay collections being promoted as memoirs or autobiographies or shatteringly new works of history. Knock it off, publishers. -

This book is a super-interesting conglomeration of facts about the culture of life and death in America. Lepore has done extensive research, and by bringing various historical events and people together, and comparing them side-by-side against the backdrop of American culture, she paints a truly intriguing picture of life in this country. Each chapter explores a different stage in a human life, from conception to death. The first two chapters were absolutely phenomenal, which I think is why I only gave this book 4 stars, because the rest of this book, while wonderful, was just not quite as excellent as its beginning.

-

Really glad I read this. The author was inspired by her mother's death and most of the chapters began as essays in The New Yorker. Jill Lepore traces the history of American ideas about life and death. The fascinating - sometimes quirky facts - she provides illustrate her talents as a great researcher and that the reader is never bored illustrates her talents as a great writer. The latter part of the book focuses on the role American politics has had on debates about life and death and is what I probably enjoyed the most. Thought-provoking and definitely worth reading.

-

Yes, it meanders, but so do great conversations with intelligent people. If you can accept that it's not a linear history, then you'll love it. Once I realized (and accepted) that the book was a history of ideas, informed by a writer with a sense of humour, then I was able to read it without judging the somewhat loose structure. Fascinating stuff.

-

Just a note that a lot of this book was previously published in the New Yorker, so will not be new to longtime readers. It's more of a collection of pieces than a cohesive whole, but the essays themselves are interesting.

-

Very interesting way to look at history as it affects various points of our lives. Well written and enjoyable.

-

I really enjoyed this quirky, slightly rambling history book. I love Lepore's voice.

-

I really want to give this only two stars based on my enjoyment (or lack thereof) but it *was* well researched and I’ve got to give her credit for that, I guess. My understanding is that the book proposes to be a history of ideas about life and death (in the US) which is a pretty wide net. The book is not even 200 pages, which was a relief when I started reading it because it is so dense, and honestly I’m surprised that I made it through. First of all, it feels more like she had researched a number of very random things and tried to shoehorn it into some sort of a framework to fit it all in one book and hit upon the thesis of “ideas about life and death.” That should cover about everything! Indeed, near the end she mentions that many of the chapters began as essays for the New Yorker. That pretty much confirms that the writings came first and the thematic framework second.

Because it jumped all over the place from subject to subject, there were a LOT of people mentioned and I struggled to keep track of who was who. A chapter would start with mention of a person or two, jump into a digression about someone they knew or were influenced by, then after THAT whole story would come back to the other person you already forgot about. Also, she just threw in these random references/jokes that just flew past me. For instance, in a chapter about chryonics (cryogenics) she describes someone as “lumpy and balding and soft-spoken but, other than that, not a bit like Peter Lorre.” Who the hell is Peter Lorre? I had to look him up: he was a character actor who died back in 1964 and who, I’m pretty sure, had not been previously mentioned in this book.

Anyway, there was some interesting stuff here but also there was JUST SO MUCH STUFF, really too much for a book this short and the theme, as I mentioned, felt cobbled together. It’s a shame because I think if she had taken a longer, broader look at just a few of these subjects I might actually remember more of it. -

This book is composed of a series of loosely connected essays that all explore the history of ideas behind the meaning of life and death in America. In other words, it explores how knowledge - or the lack of knowledge - has shaped Americans' understanding of life and death. For example, the emerging constructs of childhood, adolescence, and parenthood altered the view of the progression of life and the views on how these phases of lie should be carried out. With essays exploring ideas on conception, baby food, childhood and children's books, sexuality, marriage, life satisfaction, motherhood, old age, and death, the book covers a wide range of emerging ideas and knowledge and their impact on American thinking through the decades.

This was an odd read. Although very loosely connected, the focus of each chapter seemed widely disparate and almost randomly chosen to me, under the vast umbrella of 'life and death.' For example, although I expected chapters on the emerging ideas on conception, sexuality, and death, other chapters such as the history of children's room in public libraries, that includes a detailed account of the librarian who tried to block the readership of E.B. White's Stuart Little to be an interesting but bizarre inclusion. I realize that the essays mostly originated as standalone pieces written for the New Yorker but they still failed to cohere into one body of work for me. Likewise, the chapter on worker's efficiency and time management seemed like a segue from the rest of the text. In short, many of the chapters focused on quirky constructs in American culture that did in some way impact American life or death - but then doesn't everything?

Jill Lepore is an excellent writer and many of the tidbits in this book were fascinating, albeit randomly assorted, insights into American history. -

I can't believe this is the first book by Jill Lepore I have read. I never would have picked it up on my own, but it was part of a quarterly book box I subscribe to. It is all about the history of everyday domestic things like marriage and childrearing told in an extremely engaging manner with fascinating tidbits throughout.

If I highlighted my favorite parts of the book, I would pretty much be providing a paraphrase of the entire book, but perhaps that chapter that will stay with me the longest is the one on breastfeeding. We all know how it has come in and out of style, but the story behind campaigns to make it so were interesting. It also shows how a relatively minor issue was used to distract people from what mothers and babies really need:

"Non-bathroom lactation rooms are so shockingly paltry a substitute for maternity leave, you might think that the Second Gilded Age's craze for pumps -- especially the government's pressing them on poor women while giving tax breaks to big businesses - - would have been met with skepticism by more people than Tea Partiers. Not so." -

Read this after "These Truths" and "This America." Notably this has a quasi "harmony of the gospels" with "These Truths." We all spin our own individual stories of self, and Lepore's research and line of thought does not start afresh with a new book.

That said, I still enjoy her writing...for a modern historian, the phrasing is not packed like a suitcase for a three month trip. Neither convoluted nor antiquated, it avoids footnote quicksand likely due to her genuine love of history. This is not something I have in my DNA (despite a history major or two preceding me in my gene line.)

For me, history is not easy, like happiness (shout out to Talk Talk fans). Reading Lepore is though. -

This is essentially a collection of the authour's writings in the New Yorker but they all hang together well within a sort of seven ages of man overarching theme.

Two of highlights for me were her explorations of: an early expert on domestic science who appeared to have just one hot meal in her own cooking repertoire, which her family described as dog’s vomit on toast; and a pioneer of time and motion studies who though highly influential allegedly tended to use badly informed guesses rather than actual data.