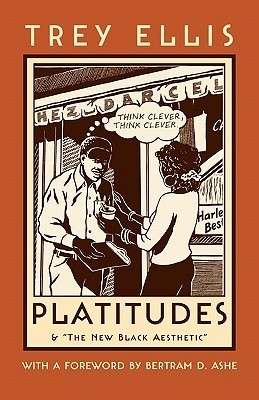

| Title | : | Platitudes (New England Library Of Black Literature) |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1555535860 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781555535865 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 224 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1988 |

Platitudes (New England Library Of Black Literature) Reviews

-

Definitely one of the most original books I've read in a long time. There's a captivating interaction between two writers attacking the same storyline (boy meets girl, boy loves girl,...) from two different philosophies (postmodernism and African-American feminism). Ellis ends up writing not only from the voices of the two authors, but their literary voices, their characters' voices. If that isn't impressive enough, the voices change as the characters interact with and challenge one another. Seriously fabulous on several levels.

-

Found this at a Habitat ReStore last summer and picked it up because the blurbs (by A. Theroux, Sorrentino, Reed, Major, John A. Williams) are crazy; I haven’t stopped thinking about it all year.

Schizoid country/city plot in the tradition of Cane and Kindred, overlaid with novel-about-a-novel self-consciousness. Black male writer sends chapters of a draft to a black female writer who revises them: his, the story of an upper-middle class teenage computer geek who can’t get laid in New York; hers, the same characters transposed to thirties Georgia (loud fat Christian women, sharecroppers, schoolmarms, racist poor whites). Cane THROUGH Kindred: past and present united in one consciousness: Earle’s coding in the morning and slopping the hogs at night. Octavia Butler wields this as political allegory (the antebellum slave regime never ended, but was diverted into new channels), Ellis as one about the literary market (careerist black authors are rewarded for turning away from the present, implying that black people only come to life under a racial caste system). The woman writer in Platitudes is showered in awards; she’s meant to remind us of Alice Walker and Toni Morrison, whom she cites as influences.

Ellis’s novel (1988) was probably written before Beloved was published—various allusions make clear that the Morrison under attack here is the Morrison of Sula and Song of Solomon. This is probably the last moment at which she was criticizable: when Stanley Crouch, who reviewed Beloved unfavorably, died in 2020, a prominent black studies theorist was still nursing a grudge and tweeted (I’m paraphrasing now) “Good riddance.” That novel secured the dominance of historical fiction in the AfAm literary market, cementing a trend that Ellis wrote Platitudes to critique, even if it pushed the historical center of gravity back from the early twentieth century to the slave past. (As Stephen M. Best has observed, the slavery-centered “Atlanticist” school of history that began with Paul Gilroy’s work followed Beloved’s lead. The novel remains the unequivocal master-text of contemporary black studies: witness Christina Sharpe and Zakiyyah Iman Jackson.)

If we think of the most prestigious AfAm novels of the last fifty years—Roots, Kindred, The Color Purple, Beloved, The Middle Passage, The Known World, The Underground Railroad—they are all historical novels, and mostly neo-slave narratives. Even an NBA-winning novel set in the present, like Jesmyn Ward’s Sing Unburied Sing, is about early-twentieth-century ghosts. Which black American wrote historical fiction fifty years before that? Neither Toomer, Larsen, Hurston, Wright, nor Ellison; before Margaret Walker’s Jubilee (1966), which was the first neo-slave narrative, only the second part of Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain approaches historical fiction (as far as I know). I was puzzled by Percival Everett’s Erasure, which assigns to urban fiction the place in the literary market that so clearly belongs to contemporary AfAm historical fiction. When was the last time you picked up a book by Sapphire or Donald Goines? or such a book won a major prize? But Morrison is inescapable: she was very canny to write classroom-sized books, most of them very short and none exceeding 350 pages, which will keep her in circulation a long time.

All this would seem to bear out Kenneth Warren’s claim that “African American literature”—or its main tradition—ceased to exist after the end of the Civil Rights movement. The novels that are now published under that rubric and win awards are historical retreads or Gothic return-of-the-repressed stories. The driving ideology of these novels is that contemporary AfAm life is circumscribed and wholly explainable by the slave past. (Teju Cole’s Open City is an exception that proves the rule: its narrator is a Nigerian immigrant, a black person whose ancestors were not enslaved. Notably, like the mother in Platitudes and the narrator of Erasure, he is an “assimilated” upper-middle class professional.) Ellis’s book wonders: Can there be a contemporary AfAm literature that does not treat slavery or Jim Crow? Is it still meaningfully “black”? Or does “black”—insofar as the literary market is concerned—name a genre, a particular set of concerns dramatized in familiar settings? -

I’ll read anything published by Vintage Contemporaries during the 1980s because I judge a book by its cover. It’s not necessary the dated design that I love as much as how it resonates to a place and time for me. This personality quirk has lead to many great books, such as the post-modern funhouse of Platitudes (read the first edition, not what’s pictured).

-

This was a quick & quite entertaining read, & the scope of its accomplishment grows in stature every time I think of it. Ellis has done a number of the most difficult things one can do in a book, & done them not only successfully but in a way that seems effortless, leaving one fulfilled but largely unaware of the magnitude of his achievement. First of all, the book is hysterical. Ellis fills his tale of young love (or lust) with all the authentic awkwardness, ecstatic highs & devastating lows that such a story deserves, while still keeping the tone light. At the same time, this is a postmodern novel in all its meta-glory, poking fun at the the world of publishing & the adults in it whose flirtatious adventures can be as laughable as their adolescent counterparts', the hyper-seriousness & the slave milieu & dialect that dominates so much African American literature, & even taking the time to parody standardized testing in a fantastic burst of absurdity. Ellis juggles all these sensibilities deftly & expertly, wrapping his high-mindedness in the most deliciously digestible candy coating one could imagine. Many more levels of reading satisfaction than you would expect from such a small package.

-

This is Post-modern with a big capital P. Trey has gone to great lengths to try and cram (or ruin if you will) this book with upside-down bits, things like a whole multiple choice test paper as a character sits an exam (didn’t read) and a complex structure; two fictional writers writing one story which is the novel ‘platitudes and sharing ideas with each other thing. It sort of works only because Trey Ellis can actually write good prose under both these guises and the characters are still sort of likeable. I found the exchanges between the two writers the lowlight, especially the feminist chick who always seems to come in just as things get going…but that’s the annoying thing about po-mo; you’re not meant to get comfortable right? The Black Aesthetic essay at the end is interesting and it is refreshing to read a hip young people’s novel from the black middle class which is what this is 80% of the time. Worth a try if you find it in an op shop somewhere and the above musing don’t put you off..

-

This book is all about sex.

There are lesser themes, too, like the battle between traditional Afro-American writing and postmodernism craziness, the struggle for feminism in literature, and some commentary about how we are constantly inundated with "culture" without realizing its importance or our own values.

But mostly it's about sex. Isshee and Dewayne talk about sex. They make their characters have sex. The metafictional, intertextual, parodic genius of this book is seriously undermined by how much sex is discussed, dissected, and basically just thrown around as a plot tool. I'm not a fan of postmodernism anyway, but this book seemed like a waste of talent. -

Boy, I loved this book when I was a kid.

-

I loved this book in a lot of ways, and recommend it - but the first half was too cluttered with writerly tricks for my taste. Another reader might love each and every one of those gambits (excerpts from an imaginary PSAT, for example), but for me it go in the way of the story. I don't need to know Ellis talented, I need to see what he chooses to do with that talent. In the end, though, I cared abou the characters and the story and found myself looking at them much differently by book's end than I did at the beginning.

-

This book is a wonderful example of a story within a story, where a correspondence between and experimental novelist and a womanist novelist evolves into two separate stories, woven around the same characters.

The Black folks in this book are way outside the stereotypical urban Black folks, giving us a rare glimpse into the Black middle-class. Ellis continued this exploration through his (uncreditted) writing of the screenplay for "Inkwell". -

A friend gave me this book because she knew it was so different from what I normally read. Needless to say, I didn't love it. Didn't even like it, really. It was too post-modern and self-indulgent to enjoy.

-

Fun to go back to this after several years. Ellis--similar to other sharp satirists I admire like Mat Johnson and Percival Everett--explodes our "stable" understandings of race in America with a whirlwind, dialogical text that tends always toward outlandishly funny and aesthetically provocative.

-

Great

-

Read for a class.

-

This novel is an example of what Raymond Federman calls “critifiction,” or fiction that has embedded within it its own criticism (as in, the author critiques the work and that critique is a part of the work). Critifiction, by being self-aware and -reflexive, by foregrounding the text and treating it as the only reality to critique, by aestheticizing post-structuralism, is straight-up postmodern. Now, the line on postmodernism as expressed in literature, like it or not, is that it is, among other things, as a consequence of recognizing language as the medium of reality, apolitical. Postmodernism – as materialist-Marxists will gladly scream at you – is irresponsible and dangerous precisely because it neglects the political realm (and does so because politics is just another Lyotardian narrative ripe for deconstruction blah blah blah). And okay so since postmodern lit. only engages social issues in order to ironize them postmodernism is a movement populated almost wholly by white male authors whose works can be read without political positions being read into them. This in part fashions the divide separating literary high fiction that orbits aesthetics and genre low fiction that claws through real-world issues. Trey Ellis knows all of this. And, knowing this, he writes Platitudes, a postmodern novel that simultaneously performs a critique of itself as a work of postmodern literature by a black author. This is about an author, Dewayne Wellington, trying to write a novel, Platitudes, about Earle Tyner, a black computer nerd desperately in love with Janie Rosebloom, a pretty girl from his private school in the Upper West Side. After a few pages Dewayne addresses the reader, telling you that the whole book thing isn’t really working out and so is putting an ad in the paper for someone to write to him and give him some help on how to proceed. Enter Isshee Ayam, a black feminist author of some renown who damns Dewayne’s work for being hopelessly misogynistic and postmodern (read: apolitical). In an attempt to redirect what she sees as Dewayne’s wayward plot she takes his characters and sets them in Depression-era rural Georgia. So, using Isshee’s chapters as loose guides, Dewayne continues Platitudes, which becomes increasingly about Dewayne’s relationship with Isshee under the guise of Earle’s relationship with Janie. What you’re reading, then, is Dewayne’s chapters, Isshee’s letters to Dewayne, Dewayne’s letters to Isshee, and Isshee’s chapters refashioning Dewayne’s characters. And all along the way Dewayne’s style develops into ever more stylistically pyrotechnic postmodern prose (kind of like the “Oxen of the Sun” chapter from Ulysses), and his characters remark on black life in postmodern America without violating whatever pretend line divides aesthetic from political fiction. This is the genius of Ellis’ work (and I don’t use the g-word lightly), he reintroduces politics to postmodernism, and shows how, amid all the language games of pomo fiction, a literary author can address social issues without ironizing them out of all recognition. Ellis himself calls this (or called this in 1988) the “New Black Aesthetic” of “cultural mulattoes,” and while we’ve come some way since then, including a drastic shift away from postmodernism itself, (and probably also shrink from the term “cultural mulatto”), this remains a brilliant novel that should be better known than it is.

-

This was definitely one of those novels you really just need to get a good grasp of or you wont be able to enjoy it. Going into it, I really thought I was going to hate it, but after I started to understand what was going on, I really liked the execution of this quite complicated read. I definitely recommend it to anyone who is interested in African-American/ Multicultural Lit. Studies. I definitely don't recommend it so anyone who just wants a read to clear their mind.

-

Structurally, it’s like that one Wire live album they did where half of it is them playing their songs and the other half feels like anti-music. I’m not even sure I can explain what I mean by that, but I loved this one. Ellis gives us three storylines - all worth becoming invested in. A little confusing at first, but rewarding by the end.

-

+1 star for usage of "fuddy-duddy" -

how is it you ask that a novel blurbed by ishmael reed, clarence major, alexander theroux, and gilbert f'ing sorrentino hasn't utterly blown up this here website? welllllllllllll here's the thing... despite how delighted and inspired i was by the melange of restaurant menus & lit parody & lists & movie trailers & standardized tests at hand here, the book sadly also kinda exemplifies everything toxic about nerd culture, w/ our protagonist earle & his friends desperate to get laid & yet deriding girls all over the place as "cows" and "prudes" and expressing sentiments like "why can't [i] just settle for a tubby acnehead"... which, i haven't even mentioned the bit where earle walks in on the love interest having sex with a male model bc she's home sick and he's bringing her chicken soup (lmao). so yeah. the metafictional elements = incredible; the proto-reddit-"nice-guy" posturing, not so much