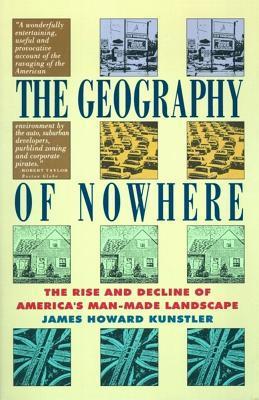

| Title | : | The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of Americas Man-Made Landscape |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0671888250 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780671888251 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 304 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1993 |

In elegant and often hilarious prose, Kunstler depicts our nation's evolution from the Pilgrim settlements to the modern auto suburb in all its ghastliness.

The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of Americas Man-Made Landscape Reviews

-

The Geography of Nowhere by James Howard Kunstler probably had more of an effect on me than any book I have ever read. This effect can be measured by my choices of living environments. I moved in constant search of livable cities, from suburban Washington D.C., to Miami, then to Seattle, and now Valencia, Spain. This book has shaped my own writing as well and I hope to publish a novel that is centered on the American suburban landscape some time soon.

The problem in America is that few people know anything other than the strip mall model of urban-suburban architecture. However, when presented with what seems like an attack on their lifestyle, they become defensive and refuse to even consider an alternative. Too many people have accepted a life in which the automobile is responsible for effecting 100% of their transportation needs (in my current model, car use represents 0%). I don’t think these people are making a choice, I don’t think they ever felt they had a choice. We have allowed the exigencies of Chili’s® parking requirements to dictate our urban planning with no voice given to the citizens. I feel that the need for a healthy and social living environment is the single most important factor in defining our happiness.

I have found Valencia to be about as close to urban perfection as I could ever imagine city life to be. The city has good public transportation as well as a fantastic network of bike trails in and around the city (as well as having wonderful weather almost year-round for cycling). Almost every urban block in Valencia is like an island capable of sustaining life for those citizen castaways who call it home. My apartment is less than one block away from a major supermarket, a green grocer, a half a dozen bars and restaurants, a shoe repair shop, a tailor, several hair dressers, a tobacconist, a pharmacy, a bakery, and a pizza take-out joint—among a few other businesses. Why anyone who lives in Valencia drives a car is beyond my capacity for understanding.

I’d like to think that my life in Spain will serve more of a purpose than just entertaining me for all of these years. On top of everything else that I’ve gained from this experience, I feel that there is one essential lesson that I can take away from all of this as an American who was influenced in my late teens by Henry David Thoreau’s Walden and my own subsequent quest to seek out how to live my life. As much as I love the great outdoors, I never looked to the wilderness as a place to suck the marrow out of life, but rather sought to fight against the urban explosion which had been sending people farther out into the suburbs and away from city centers. I slowly began to learn the importance of our man-made geography, the way we make our cities, the way we live our day-to-day lives, and I wanted to live mine better.

In fact, for a good portion of my life I never really had a adequate understanding of just what made up a city. For too long, I defined it as simply a conglomeration of homes, and businesses, and schools, and everything else necessary in our lives, all stitched together by a fabric of roads. What really defines many people’s lives is the automobile, although they’d be loath to admit this. It took me a long time to realize that something was wrong in my life, that something was missing, that I needed a change, or possibly that I needed to change. Both the realization that something was wrong and the solution came about in increments and almost by accident over the course of many years and a few different time zones. Now it’s impossible for me to imagine living in any other manner.

Here is something I wrote about my city and neighborhood here in Spain:

https://leftbankview.blogspot.com/201...

I lived in downtown Seattle for eight years before I moved here and life in that city was similar to how I live now. I had a car but it was more of a recreational vehicle, like a jetski, something I used on weekends to get out of town. Here I can take the train (on the local trains, I can take my bike). -

James Howard Kunstler, prophet of doom, blogger ("Clusterfuck Nation"), author, novelist, wrote this book way back in 1993, but it has that timeless feel. Not a whole lot has changed, except apparently we've pushed doom a little further off into the future. "The era of cheap gas is drawing to a close," he warned us, meaning death for the suburbs as many people would no longer be able to afford to drive. Well dang it if cheap-ish gas prices aren't here again, after their scary highs of '08.

Kunstler's concern is the built environment; specifically, how horrific it is. The world around us is designed for cars, not people. We owe our environment to the metrics of traffic engineers, the zoning boards who listen to them, to government policies that subsidized cars and interstates but allowed streetcars and trolleys to die out. Even where zoning boards have tried to limit sprawl and encourage charm - say, by forcing houses onto 2 acre plots - they've only encouraged sprawl by pushing dwellings further and further out from towns, in 2 acre increments. And many of the most beautiful and historic homes that still stand in small town America would be illegal by current zoning standards. Living in a world designed not for us, but for our cars, engenders feelings of alienation in us. It's why office parks sit amid vast lagoons of cars, why split level house facades feature huge gaping garage doors, why Ramada Inns are unashamed to have loading docks and metal fire doors front onto the streetscape. If you've ever tried to walk somewhere in the suburbs, or the exurbs, where there were no sidewalks, maybe just a little grassy rut next to eight lanes of traffic, you'll want to read this book. If you've ever walked through a charming New England town with buildings on a human scale and old growth trees lining the streets, and then a fringe-urban warehouse district cinderblock moonscape, and wondered why one made you feel good and the other didn't, and how they both managed to get built, this book is for you.

Kunstler writes in a biting vernacular. Suburban stores are "shopping smarm." Individual houses sit on "big blobs of land." And everywhere, there is crud: "commercial highway crud," "creeping crud architecture of suburbia," "the modern crudscape." Our human habitat is "trashy and preposterous." The Swissman Charles-Edouard Jeanneret "took the hocus-pocus name Le Corbusier." (Kunstler despises Modernism.) The Red Barn fast food restaurant "is an ignoble piece of shit that degrades the community." All over American suburbs "there are the dreary voids we call front lawns and dull exercises in miniature vignette-making known as landscaping with shrubs."

In a chapter devoted to the glumness of fakery, he visits Atlantic City. "Standing on the Boardwalk this mild October Day, one beheld the Trump Taj Mahal with that odd mixture of fascination and nausea reserved for the great blunders of human endeavor." At Disney World, "after paying $32.50 for admission [in today's dollars a one-day ticket costs $79:], you are efficiently herded onto a ferryboat for a short ride across an artificial lake to the entrance of the Kingdom. This will be the first of many crowd-control experiences - and resulting lines - that add to Disney World's air of fascism. The boat ride is also a psychological device. Making you enter the place by stages, the Disney "imagineers" emphasize the illusion of one's taking a journey to a strange land - as if driving over 1500 miles from another corner of the nation was not sufficient..."

There are moments when his judgments come a little too close to snobbery for my comfort. It's not the snobbery of wealth or education but of aesthetics: people whose aesthetic choices are subpar - say, someone living in a ranch house with a rusty auto and a torn plastic wading pool in the yard - are to be pitied. "You could name a housing development Forest Knoll Acres even if there was no forest and no knoll, and the customers would line up with their checkbooks open. Americans were as addicted to illusion as they were to cheap petroleum." Or, maybe they don't have many choices. Maybe Forest Knoll Acres was affordable and close to work and its buyers were well aware that it wasn't some pastoral Eden - but knowing they were participants in a developer's illusion wasn't the most dire fact of their daily life. I prefer not to tie individual aesthetic choices so closely to virtue or lack of it. Not everyone can live in Seaside, Florida, or on Walden Pond.

He treats the built environment holistically: geography is related to architecture, which is related to economics, which is related to sociology. I have to admit I'd never thought of ecology and economy being as closely related as their roots would indicate. Ultimately it all has to do with private ownership vs. public responsibility. It's the story of America. I'd also never directly related the expenditures of the interstate highway system to anything else, but "because the highways were gold-plated with our national wealth, all other forms of public building were impoverished. This is the reason why every town hall built after 1950 is a concrete-block shed...and other civic monuments are indistinguishable from bottling plants and cold-storage warehouses."

This is an utterly harsh indictment of the way we live, and the manner in which we've surrendered decision-making unthinkingly. It's a plea to heal our "spiritual deformities" (yes, it really is that bad) by maintaining and building better communities and actually caring about them. -

There is nothing like a little James Howard Kunstler to make you feel like a complete asshole and Capitalist whore. His newest prophesy is that the American suburb is dead, but this book only predicts that with its strangely-plausible sounding doomsday warnings and vehement attacks against anyone so blind enough to want the myth that is the American Dream.

The book takes a fascinating look at the forces that drove the rise of individual landownership and the suburb as currently accepted in modern society. his examinations of human psychological and anthropological tendencies are depressing, but spot-on as far as this non-psychological/anthropologically -challenged reader can tell.

While I can heartily agree with him on the bulk of his logical reasoning, I just don't like that I put the book down feeling guilty about growing up in suburbia and being raised with the virtues of "typical" suburban life instilled in my brain. I'm trying to break free, but the concept of a backyard keeps sucking me in! don't look at me, I'm hideous...

I highly recommend this book to anyone who happily lives alone in a house in the suburbs and commutes to work alone in an automobile every day. prepare for your world to be rocked. -

"The Geography of Nowhere" tends towards the polemic, but through most of the book I found myself agreeing with Kunstler's ideas. His basic premise is that the fundamental American bias towards private property rights has created a culture weak in community- and this bias has combined with an over-reliance on the automobile to produce "nowhere" places- suburbias with no-center, endless highways of stripmalls, and millions of units of crap-housing. He's not optimistic about the future of this civilization we've created: once the oil runs out, or the environment goes bad, or we go insane from spending weeks every year in our cars, he believes we're going to be somewhere beyond fucked.

His writing is at its best when he's describing specific places in America- cities that he feels have failed, like Detroit or LA, towns that he feels are broken, like Woodstock, Vermont, or weird capitals of illusion like Disneyworld. He's less good when he's giving a compressed history of architecture and urban planning in America- that part felt like a blizzard of names and styles, and with no pictures, I had to do a lot of Google image searching to understand his references. And I felt the ending of the book was pretty weak: his proposed solutions for the problem of suburbia all felt kind of half-assed, like building new, denser cores into the suburban wasteland, rather than just knocking it all down.

One other thing that bothered me about the book was the absence of any mention of Jane Jacobs or her ideas. I think that reflects Kunstler's fundamental bias towards small town living: he's lived upstate in Saratoga Spring for most of his adult life. But the problems he describes are really only solved in cities, and Jane Jacobs ideas about what makes cities work are key to understanding what makes suburbs not work. I could imagine Jane Jacobs dismissing a lot of what he has to say about saving suburbia as meaningless and besides the point- I don't think she'd find anything there worth saving. -

Kunstler's analysis of the sad suburban situation is mainly right-on. Unbridled private enterprise has destroyed public transit. Roads and buildings designed predominantly for private car access create problems for the human inhabitants of that environment, making it impossible to do without a car for the simplest of tasks in many places. Local zoning laws are often inane and archaic. Ditto building codes. Sprawl and congestion go uncontrolled because city planners are blind to the big picture.

Thus, it's very unfortunate that Kunstler stuffs this book with such bombast and sanctimoniousness (occasionally segueing into moist-eyed sentimentalism) that it's often difficult to take him seriously. His failure to divorce personal preferences from factual arguments hurts his analyses tremendously, rendering them shallow, inconsistent, and incomplete. The resulting proposed solutions are largely simplistic, and even oddly idiosyncratic, in some places. In other places, things descend into outright "WTF?" territory--speaking of the advantages of mixed income neighborhoods: "The children of the poor saw how sober and responsible citizens lived." Seriously.

Thankfully, Kunstler just reads like a very angry Mr. Mackey ("Modernism and cars are baaad, mmmmkay?") most of the time. His anger is understandable, however; you'd be pissed too, if you lived in a town where people beautify their front yards with large plywood cutouts of urinating children and butt cracks.

In the end, this book is still a worthwhile read. It outlines a very important but unsexy problem, lays out some interesting ideas, and hints at a way forward. It's depressing to see how little the North American transit/planning landscape has changed since the '90s, when this book was published, that despite our growing energy woes, the toll of lengthening commutes, and the increasing fetishization of the private to the detriment of the public. Read it with a hefty lump of salt, and be prepared to roll your eyes a lot. -

This is book is largely a rant--well-researched and eloquent--but a rant nonetheless. Overwrought with cynicism, it is hard to distinguish Kunstler's reasonable concerns from his own sense of nostalgia. He draws some erroneous parallels (e.g. holding Disney World to the standard of anything but an amusement park) but does make an effective point regarding how U.S. citizens were ill-prepared for the after effects of the heyday of the automobile.

Fundamentally, Kunstler's cynicism aside, he's an advocate for renewed interest in civic planning, decreased dependency on fossil fuels, and models of sustainability. He presents Portland, OR as the best model for a city and the community of Seaside, FL as the model for a smaller town. He sees urban planning as the opportunity to develop while respecting the present landscape and enriching sense of community and public space.

The weakness of the book lies in the author's bitterness, which disguises his very real passion for the topic. The

saving grace is that given most of his likely readership, he is preaching to the choir who understands his anger. This choir will understand that Kunstler embeds important lessons in his bleak diatribe--lessons worth embracing. -

In this book, Kunstler covers the history and development of town planning and suburbification with a definite chip on his shoulder. Starting with colonial times, he examines how we have used (and misused) land for individual, rather than group purposes. The great expanse of America was ours for the taking, and take it we did, throwing aside the concepts of villages and civic harmony.

He vilifies the automobile industry, blaming it for the banality of suburbia and the destruction of community, gobbling up farmland in the name of urban sprawl. Examples of exploitation include Detroit, Saratoga Springs and Atlantic City. Las Vegas and Disney World were other obvious targets, of course. Only rarely does he point out who's doing it right: Portland Oregon, and Seaside, Florida are two of his examples.

While Kunstler has many valid points and does an excellent job of bringing together disparate elements of our history to show how they shaped our idea of neighborhoods and communities, he does so with such negativity and smugness that I found it difficult to take him seriously at times. The repetition of such slangy phrases as "scary places", "jive-plastic" and "crap" also detracted from the gravity of the discussion. I'd be interested in seeing the same material covered a little more dispassionately, and with more suggestions on how to make small changes in the right direction.

Recommended to those interested in community planning from the viewpoint of everything that we've done wrong. -

Sometimes people tell me I'm humorless, that I over-intellectualize, that I need to chill out. Well, in that regard, James Howard Kunstler makes me look like fucking Vinny from Jersey Shore.

The Geography of Nowhere, is, above all else, a rant. A very entertainingly angry rant, but a rant. While I enjoyed reading much of it, it doesn't exactly have an academic basis-- the foundations for his claims are shaky at best, and when he makes claims about the nature of building and space, he doesn't justify them.

To a certain extent, I agree with him-- America's suburban spaces are awful, dehumanizing, and hideous, and I would like to see them eradicated from the face of the planet. But rather than anything productive or even really very thought-provoking, he just offers us an anti-modernist screed, and promotes a wishy-washy sort of new urbanism as an antidote-- something that really, I feel, doesn't work. -

Great, now I'm a snob about urban planning too.

-

This was a drab book about a bleak subject using bland language. Somebody or something peed on the author's cornflakes as he got up on the wrong side of the bed. And it was the automobile. Instead of harping on the negative consequences of vehicular life I would have like to have some visionary solutions to get us out of the abscess. One chapter would have been more than enough to point out how a lifestyle dependent on automobiles is detrimental. There were two good chapters: #6 Joyride and #11 Three Cities, which gave a few accomplishments. For instance citing Portland as a positive city.

Being a quarter of century since the book came out it might have been insightful (or just discouraging) on how things got worse. I wonder what the author might have thought of the Detroit RecCen now being a GM complex (from Ford roots), or big box stores in many communities being the same so there is little community identity, or kids no longer walk to school as they are dropped off and picked up.

Mentioning how porches used to be useful or how balconies need to be more than six feet in depth is not going to attain the kind of turn around we need. How about cities with huge complexes void of automobile traffic or just communities of a score of homes not needing a driveway to each residence? What would they look like? What needs to drive their development? Kunstler does note that developers need/could be the driving force to overcome restrictive requirements. For instance in Calgary they overcame the requirement to have to provide parking for a downtown complex (as people downtown didn't need cars) reducing the construction costs and thus reducing the rents.

Things could be better but how do we get out of the faulty cycle of vehicular obsession? The bonus would be less CO2 emissions. -

Things you might hate after reading this book: automobiles, parking lots, garage doors, flat roofs, building codes (the ones that don’t make sense), zoning laws (some but not all), and tourist attractions. Kunstler makes a compelling argument about how towns have lost their relationship with individuals due to the automobile replacing walking as a primary mode of transportation. This has allowed for the spreading out of individuals, which can be seen as negative as we lose pristine land to development and fill our environment with toxic waste from cars and corporate expansion. That is just at the surface level, but he dives deeper into issues that are behind the factors of these changes and how to address them. His history of architecture and change of style overtime (dry at times but once you get through it, it will all make sense in the end) is interesting and explains the different styles that we see today, why they developed, the shift from wood to brick and stone as a building material, and how this factor into the aspect of a “no-place,” which is probably one the most interesting geographical discussions ever. Read up on the idea of a no-place as it is absolutely fascinating.

Kunstler hits on various socio-cultural and human geography aspects. The first being this idea of separation that results in cycles. This separation is caused by the spreading out of individuals who decided to leave areas that then become low-income housing areas; areas now faced with challenges of redevelopment and revitalization in an attempt to bring back those who have left for the suburbs (see his Three Cities chapter and the section on Detroit, Michigan). Most cities are trying some aspect of mixed incoming housing (Nashville, TN being an example in the news recently) and wait to see the results.

The second being the idea that the car has become so prevalent in American society that those who are seen walking the streets today are stereotyped as poor or must be “up to no good.” He does not dwell on this point, but I think it is important to recognize the shift made as we went from walking as the primary form of transportation to cars, and how that impacts our thinking of other individuals.

Finally, he repeatedly mentions that, “...commonly, the experts do not live in the communities they are paid to advise.” This issue remains a big topic of discussion as communities going through post-industrial redevelopment are advised by outside corporations that do not take the time to understand the communities in which they advise and therefore the impact projects may have on these communities. Bottom-up redevelopment still struggles to prevail in a lot of places.

My main criticism of this book is that he provides a lot of examples of places that have had success in pedestrian-friendly development, however, those are the shortest sections. A lot has changed since the book was published so more could be written today, but I wish the section praising Portland, Oregon for its developmental success was just as long as the section critical of Los Angeles. What I enjoy most about Kunstler’s writing is his sarcasm, which will literally have you laughing. He is absolutely biased (what author isn’t) and has a clear agenda here, but regardless of “tone,” he presents facts while appropriately displaying his opinions. -

Kunstler:

'Born in 1948, I have lived my entire life in America's high imperial moment. During this epoch of stupendous wealth and power, we have managed to ruin our greatest cities, throw away our small towns, and impose over the countryside a joyless junk habitat which we can no longer afford to support. Indulging in a fetish of commercialized individualism, we did away with the public realm, and with nothing left but our private life in our private homes and private cars, we wonder what happened to the spirit of community. We created a landscape of scary places and became a nation of scary people.'

Try to read this book and have any love for this country! Though I now have a deeper love for livable pockets like the IC. -

Second Look Books: The geography of nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape by James Howard Kunstler (Simon and Schuster, New York 1993)

The great modern classic, “The geography of nowhere,” by James Howard Kunstler, describes the American predicament of having nowhere to go, at least nowhere to go that looks any different than any place else. Everyplace (and any place, and anyplace) has, in this country, been built mostly since World War II, a “tragic landscape of highway strips, parking lots, housing tracts, mega-malls, junked cities and ravaged countryside that is not simply an expression of our economic predicament, but in large part a cause.” Underlying this predicament is the Automobile, the corporations who manufacture it, the people who rely on it, the politicians who make special provision for it in the laws. Beyond that are the city councils and state legislatures that zone, tax and legislate to give primacy to the Automobile. What more perfect expression of the primacy of the Automobile than Suburbia—that bland, visionless, pathless, sidewalk-less, porch-less, soulless wasteland? Front and center—the TV, the huge three-car garage, the cul-de-sac given some English foxhunt manqué name.

Like most people my age (70), I fell in love with cars early on. Getting one’s first car meant freedom, defined as speed and absence—not being chained to responsibility, parental control and the grid of eyeballs inspecting one’s every move. As a kid, my town was a fantasyland of brick streets over which huge elm trees created tunnels of shadow and shade; massive and mysterious Drive-in theaters where couples went to neck, lively downtowns full of kids “dragging” to be seen and see, hundreds of wiseacres, cheerleaders, nerds, hoods, jocks and wannabees, some with their own cars, others (like me), with daddy’s. There was, actually, someplace to go.

No book explains better how this all came to be than Kunstler’s. In it he argues that the great suburban build out is “over” and that it has been a disaster for our civilization and we “shall have to live with its consequences for a long time.” The spread-out cities, vast suburban and now ex-urban tracts composed of curvilinear streets lined by faceless cheap housing, malls and parking lots, has “bankrupted” us both personally and at every level of government. A further consequence, Kunstler argues, is that “two generations have grown up and matured in America without experiencing what it is like to live in a human habitat of quality.” Slowly but surely being lost are whole bodies of knowledge and sets of skills that took centuries to develop and were “tossed in the garbage”, chief among them a culture of Architecture lost to Modernism and its dogmas. Also lost was the culture of town planning, early on in the modern era handed to lawyers and bureaucrats dedicated to the automobile, the highway and commercial real estate, and lately lost to the burden of suburban born and bred “conservatives” whose ideologies do not include aesthetic insight.

We all now live in what Henry Miller early on called “the air-conditioned nightmare”, though even Miller, a genius with antennae for the truth, probably didn’t foresee the full implications of the destruction of our built and natural environment.

It is worth quoting at length Kunstler’s concluding observations:

“But let’s assume that we now face the future with better intentions. The coming decades are still bound to be difficult. We will have to replace our destructive economy of mindless expansion with one that consciously respects earthly limits and human scale…We’ll have to give up our fetish for extreme individualism and rediscover public life. In doing so, we will surely rediscover public manners and some notion of the common good.

We will have to downscale our gigantic enterprises and institutions—corporations, governments, banks, schools, hospitals, markets, farms—and learn to live locally, hence responsibly. We will have to drive less and create decent public transportation that people want to use. Will have to produce less garbage (including pollution) and consume less fossil fuel. We will have to reacquire the lost art of civic planning and redesign our rules for building.

There is a reason that human beings long for a sense of permanence. This longing is not limited to children, for it touches the profoundest aspects of our existence: that life is short, fraught with uncertainty and sometimes tragic. We know not where we come from, still less where we are going, and to keep from going crazy while we are here, we want to feel that we truly belong to a specific part of the world.”

Amen, brothers and sisters. -

A harsh truth comes across with a negative tone early in the book, however the late chapters use clear real world examples and provides decent solutions. For a book published in the early 90s it’s interesting to see how relevant the information remains. Furthermore, the age of this book provokes some detailed retrospective questions regarding public space in the early 2000’s and 2010s.

The book shows it’s age in some ways (for instance, using he/him pronouns for home ownership or vehicle operator and she/her pronouns for parenting topics) however, the overarching message tends to override these nitpicked annoyances.

*EDIT*

The nitpicks are not overridden. The author is a raging trump supporter which is hilarious because he spends an entire portion of a chapter bashing Atlantic City trump casinos. Nevertheless, the messages in the book are very solid, however in the current age Kunstler is a conspiratorial, right wing nut. -

What is place?

I ask myself that often, because it's something I notice and can never nail down. It's always been easiest to notice a vacuum of place, normally when I have to toddle off to a Target in the Big-Box shantytown on the periphery of a city.

"Why do people like this? It's all the same."

Next to the Target is a Costco which neighbors a Best Buy that shares a parking lot with a Jiffy Lube and Toys 'R Us. If you're hungry, your choices are fast food, la-di-da fast food (Panera), or a sit-down restaurant that's weirdly expensive ($15.25 for chicken marsala at Olive Garden! It's not that Olive Garden sucks, it's that fifteen bucks is way too much to pay for something that came pre-made in a Sysco catalog).

Every town in America seemingly has this district, and that is weird. I personally find it repellent, ugly, and damn inconvenient ("You mean nobody installed a sidewalk for the half-mile journey between stores!?") I didn't always hate it, but the more I live in a city with unique food, shops, and scenery, the more I loathe the trek to the concrete flatlands of chain stores.

James Kunstler hates it too, and in far less kind terms. His book is angry and bitter at the unwalkable world we've built in the name of the automobile, and yearns for locality and the stability it brings to a town. Besides it being a labor of love for a disappearing world (and perhaps more so a screed against the ugly landscape in its place), he also examines the zoning laws that often mandate acres of parking, and how those statutes lack nuance for the community they serve. Zoning laws are often imported whole hog from other suburban developments, which is why each suburb and WalMart is nigh identical.

I knew we lived in a world of carefully measured easements and borders, but I didn't appreciate how restrictive those are, and how that prevents a close-knit community. Houses must be x feet from the sidewalk (thus you have no need for a porch and cannot talk to neighbors on the street). Parking must be available in front of the building (meaning no storefronts that open to the sidewalk). Land may only be sold in x acre parcels (which minces farmland while salting the earth for a small business owner). They're all small things with good intentions, but the end result is a world that is only accessible by automobile.

I realize that much of this is personal taste, and I'm fighting forces much larger than myself (which may well be the theme of the book). A lot of people love shopping at Macy's and eating their Subway sandwiches. That's fine, even if my last trip to Subway tasted like onion and lukewarm mayonaise (never again). The more I read, the more I'm learning that the American identity is one of self-reliance and utter independence. GoN notes that the American household is a pretend manor house devoted to the production of comfort. This house is isolated from others so we can have our space and back yards, and we drive alone in our cars to our offices, which are far away from home, which is far from the places we shop. It's dualism, but of the daily functions of life.

This book is educational, but it is not at all objective. It's one man who is upset at the vast nothings we build because we lack creativity or foresight for better. I agree with him, so I liked it, despite its heavy-handedness. If you enjoy the mall, you might not take kindly to his labeling of such as "ugly". Aesthetics play strongly in Kunstler's theology of space, and these rules are not always well defined. But he does make a call for a definite urban plan, and presents examples of successes, rare as they may be.

This is not a set of instructions for life in the future. It's pessimistic. It has none of the save-the-world glamor of a TED talk. But it is achingly honest and human.

I came for the cranky man yelling, but I stayed to learn why the landscape is shaped as such. -

Prince Charles accused them of being artless, mediocre and contemptuous of public opinion. The old joke was that they had inflicted more damage on London than the Luftwaffe, but it wasn’t funny and nobody was laughing.

‘They’ are the post-war urban planners and ‘they’ have a lot to answer for. But the bumbling British versions are as nothing compared to American counterparts reinforced by ludicrous zoning restrictions and lunatic laws.

It’s why the simplest of tasks here almost always require a journey by car. It’s why strip malls brutalize the landscape, appalling ‘architecture’ abounds and attempts to escape become an engine of urban sprawl.

Try buying a loaf in the suburbs, or looking for a corner shop that sells fresh fruit and veg. Honestly, don’t bother. It’s a fool’s errand. The closest you’ll get is non-food at the nearest gas station.

More than 20 years ago author James Howard Kunstler poured his rage onto the page about the state of America’s “crudscape” and in the intervening years not much has changed.

His withering invective is a delight to read. He’s beyond grumpy. This is a crimson-faced man ranting in foam-flecked, spittle-spraying fury as he pours contempt onto anyone and everyone who has contributed to the monstrous blight

Here’s a sample: “Eighty per cent of everything built in America has been built in the last 50 years, and most of it is depressing, brutal, ugly, unhealthy and spiritually degrading – the jive-plastic commuter tract home wastelands, the Potemkin-village shopping plazas with their vast parking lagoons, the Lego-block hotel complexes, the “gourmet mansardic” junk-food joints, the Orwellian office “parks” featuring buildings sheathed in the same reflective glass as the sunglasses worn by chain gang guards, the particle-board garden apartments rising up in every meadow and cornfield, the freeway loops around every big and little city with their clusters of discount merchandise marts, the whole destructive, wasteful, toxic, agoraphobia-inducing spectacle that politicians proudly call “growth”.

It wouldn’t be much of a book if it was just a rant, though. Kunstler takes a scholarly stroll through 400 years of New World development, points out features of special interest, changes that could, and should, be made and makes a delightful, spiteful, opinionated companion along the way.

As he explains, the rise and demise of America’s man-made landscape has all the usual venal underpinnings you’d expect, but the book also includes some of the well-meant but subsequently disastrous efforts to create idyllic surroundings.

As far back as the 1950s economist JK Galbraith was suggesting that the US had become a nation that tolerated “private affluence and public squalor” and there are echoes of this throughout Kunstler’s assessment.

Civic pride has been supplanted, individual rights have trumped wider public benefits and coherent communities have been ghettoized by wealth apartheid.

Kunstler reserves most of his bile for the effects the car has wrought on everyday life and the landscape, but there’s plenty left for the automobile’s “master builder,” Robert Moses, who favored the car over public transit at every opportunity.

When he wrote the book in 1994, Kunstler thought rising gas prices and environmental concerns would force the US to rethink its ideas about urban planning and community. Not so. Fracking will keep the wheels turning for a long while yet. And while our heads are buried in the tar sands the temperature keeps on rising. -

This book is a critical story of how the American landscape went from age-old agreements between city and country, agreeable walkways, and shared public spaces built on a people-size scale, to a modern auto-suburban wasteland nation, devoid of life, humanity, civic beauty, mysteries and cozy shadows on crooked streets.

The theme is not new. A bunch of history is told in it, and Kunstler will attempt to explain how this came to be. The historical argument is: America before industries was nice, although, because of the independence war, property ownership to Americans always meant freedom and capital gain, not stewardship. When the industries come, mass scale, workers, pollution and slums set in, which creates a “yearn to escape” the city. This happened in the XIX century, the age of romanticism. Get all that together, and you have the idea of suburbs: close to nature, away from city.

So this is the American paradox: suburbs are not towns, but they try to look like they are. They depend entirely on the cities from which their residents are fleeing. So, on a Monday morning, suburbs are emptied when people go to the city to work, and they become wastelands (the same happens in the city when everyone goes back home). Suburbs are, in a way, a fake – lovely houses that look like a home in an awesome place, but are detached from a community or a strong public space, and are repeated one house after the other, in tedious, monotonous, fragmented, identical and scary repetitions. They are, of course, only possible because cars enabled enormous gains of mobility, which turned America into a constant mobility nation. In the end, urban planners were given the functional task to make all that work, and they invented zoning codes. Hence you have ultra-large asphalt streets in suburbs, wastelands of empty parking lots, constructions with abysmal space between them, billboards, highways, gas stations and car dealers everywhere and so on. When everything is mobility, everyplace becomes noplace.

This story is told in a quite friendly way, but this does not account for the book’s most interesting and controversial moments. This moments are, of course, Kunstler judgments on this situation. It’s important to point that, however much history is put in it, the discussion on how bad American landscape actually is always falls often short on supposedly self-evident truths. I agree with most of them – in fact, they changed my whole way to see cities – but I don’t know if you would. Kunstler’s critic is very subjective and personal – not technical or philosophical. So American cities are “scary”, endless avenues with car dealers decorated with colorful flags and billboards are “cartoonish”, suburbs where people walk two or three hours without seeing anyone are “inhuman” – but is this all objectively true, or he’s just a nostalgic?

There is no aesthetical argument to prove that this criticism is objective reality and not nostalgia. Also, no discussion is made to prove that, with industries and oil, America could ever have developed in another direction. You won’t get those two questions answered in this book. So, if you've never felt anything odd in American landscape, or you’re not already conservative regarding your aesthetic judgment, I recommend you not pick the book. If you have one or both of these qualifications, you should read it, and you’ll see it as a very powerful and enriching book. -

A rant. Pure and simple. But a rant with which I, mostly, agree.

Kunstler demonizes our history of development in America in a very readable, if sarcastic and snarky, prose. Written 15 years ago, the complaints are still with us today; why does America feel so ... so ... wrong?

Of course, if you don't feel like America is "wrong," you'll hate this book. But Kunstler is operating on his strong feeling that it IS wrong. And will continue to be until we start building on a human scale, rather than on a scale based on the automobile. In the 1960s, Lewis Mumford said of "development" in America; "the end product is an encapsulated life, spent more and more either in a motor car or within the cabin of darkness before a television set."

And this is what's wrong. And it is because of our history. America was founded without an aristocracy to support the arts and architecture. It also was founded on the concept of freedom to take the land; manifest destiny. Endless land, so why the hell should we cram together in a city?

At first, this worked out ok because transportation possibilities required things to be central; rivers, canals, railroads. There were towns with centers and then outlying farms. Then industry arrived and factories started to make our cities undesirable. Then elevators arrived and our buildings got taller and taller. And slums spread. And the rich took flight and the cities started to die. Kunstler writes, "In America, with its superabundance of cheap land, simple property laws, social mobility, mania for profit, zest for practical invention, and Bible-drunk sense of history, the yearning to escape industrialism expressed itself as a renewed search for Eden. America reinvented that paradise, described so briefly and vaguely in the book of Genesis, called it Suburbia, and put it up for sale."

Early suburbia were attempts to return to Arcadia. And during the railroad/horse/carriage era, this worked for a while, but then the car came along and made Arcadia Suburbia, with all the gardens, lawns and turrets multiplying at a rate that they became stage sets rather than bucolic settings. Some people lost faith in Arcadia and embraced Modernism, which, according to Kunstler, was just as bad, as Modernism "dedicated itself to the worship of machines, to sweeping away all architectural history, all romantic impulses, and to jamming all human inspiration into a plain box."

Modernism became prominent with the help of Stalin and Hitler, who both loved traditional architecture and ornament and neoclassicism. Therefore, in the land of the free, there would be no whiff of Fascism or Nazism or Communism and, therefore, no neoclassicism.

So American space began to be less about forms and more about symbols. Communication. Advertising. Vast developments of decorated cinderblock sheds connected by miles and miles of soulless concrete passageways and fronted by acres of asphalt for the parking of those machines that enabled one to travel the miles required of our new landscape became the norm. Then postmodernists started ironically referencing nature attached to the concrete paradise; plywood butterflies on garage doors, rusticated facades, fake windows. "Here, you nation of morons, is another inevitably banal, cheap concrete box, of the only type your sordid civilization allows, topped by some cheap and foolish ornament worthy of your TV-addled brains."

And it happened because America became so enamored of the automobile. Kunstler writes, "There was nothing like it before in history: a machine that promised liberation from the daily bondage of place. And in a free country like the United States, with the unrestricted right to travel, a vast geographical territory to spread out into, and a nation tradition of picking up and moving whenever life at home became intolerable, the automobile came as a blessing. In the early years of motoring, hardly anyone understood the automobile's potential for devastation - not just of the landscape, or the air, but of culture in general." The car would simply make it easier to live in either the city or the country. No one expected it to alter the arrangement of things in both places. But Ford made the car supremely affordable and city planning boards were dominated by realtors, car dealers and others with interest in making the world a better place for cars, not humans. The car, or, rather, the combustible engine, made life better for the farmer but it also, in Kunstler's words, "destroyed farming as a culture (agriculture) - that is, as a body of knowledge and traditional practices - and turned it into another form of industrial production, with ruinous consequences." The farmer turned to machines but machines cost money, so they also turned to mortgages. And without horses, there was no manure, so farmers had to buy fertilizer. And as farming changed from crop diversification to monoculture, they had to purchase pesticides. And soon it was too much for the individual farmer. Agriculture was dead. Agribusiness was born. And now all we eat is corn.

But that's another story. Or is it?

Meanwhile, city planners were betting the bank on the automobile culture and building miles upon miles of concrete for use by individual automobiles. No mass transit was developed in conjunction because the entire industry was controlled by one man, Robert Moses, and he thought mass transit was a bottomless pit. "Mass transit does not produce profit. It is a social good, but a financial loser."

So highways cut through cities. Suddenly impervious walls of concrete made it impossible to get from one place to another on foot. America began to dance to the tune of the automobile and, as a result, lost its sense of human scale. And lost its soul.

In the midst of this was the depression, which created the FHA, which created the financing schemes that favored suburbia over urbia. FHA would guarantee loans for houses that were new, outside dense cities. It red-lined much of our inner cities; drew an imaginary line around dying neighborhoods and said, "Don't even think of buying here because this part of town is heading down the tubes and we don't back losers." Another knife in the dying back of urban life.

Then World War II came and when it went, Levitt made housing even more affordable. Kunstler writes, "Classes of citizens formerly shut out of suburban home ownership could now join the migration ... The American Dream of a cottage on its own sacred plot of earth was finally the only economically rational choice ... but this was less a dream than a cruel parody. The place where the dream house stood - a subdivision of many other identical dream houses - was neither the country nor the city. It was noplace. If anything, it combined the worst social elements of the city and country and none of the best elements. As in the real country, everything was spread out and hard to get to without a car. There were no cultural institutions. And yet like the city, the suburb afforded no escape from other people into nature; except for some totemic trees and shrubs, nature had been obliterated by the relentless blocks full of houses."

But people moved there and the infrastructure supported the moves; in 1956 Congress approved the Interstate Highway Act, which saved the economy from recession and called for 41,000 miles of new expressways, 90% paid-for-by-the-federal-government. The highways then created more patchwork "development," which created more highways ... and on and on.

Then it was 1973 and the Arab oil embargo, for a brief, shining moment, made America rethink the oil-hungry system of life it had built. The country entered a stagflation. Jimmy Carter made his famous malaise speech, chiding America for its stupidity. Kunstler writes, "Carter told Americans the truth and they hated him for it. He declared the 'moral equivalent of war' on our oil addiction, and diagnosed the nation's spiritual condition as a 'malaise,' suggesting, in his Sunday school manner, that the nation had better gird its loins and start to behave less foolishly concerning petroleum. The nation responded by tossing Mr. Carter out of office and replaced him with a movie actor who promised to restore the Great Enterprise to all its former glory, whatever the costs."

And Reagan got lucky. Really lucky. The oil cartel fell apart and failed to keep prices jacked up. Poorer nations got in the act and undercut prices even further and oil became cheap again. So all the ideas of investing in alternative energy were dropped. We were still a great, sprawled, oil-hungry nation and would continue to be so. Oil will always be cheap and available. Right?

So we continued to develop our idea of paradise; roads, parking lots and buildings designed for ease of auto access. Kunstler writes, "Travel is now incessant and inconsequential ... The road is now like television, violent and tawdry. The landscape it runs through is littered with cartoon buildings and commercial messages. We whiz by them at fifty-five miles an hour and forget them, because one convenience store looks like the next. They do not celebrate anything beyond their mechanistic ability to sell merchandise. We don't want to remember them. We did not savor the approach and we were not rewarded upon reaching our destination, and it will be the same next time, and every time. There is little sense of having arrived anywhere, because everyplace looks like noplace in particular."

Our buildings relate poorly to other buildings and don't create a sense of community. Our towns go and go and go and go and you can't do anything without turning the ignition on your car and driving for ten minutes. The failure to own a car is "tantamount to a failure in citizenship, and our present transportation system is as much a monoculture as our way of housing or farming." Our national economy has become so gigantic that local economies cease to matter. And when local economies fail, local communities fail. So instead of a main street we have far-flung houses, a Wal-Mart and the Kum-and-Go. Regional planning is viewed as unAmerican; you can't tell me what to do with MY land. Public realm ceased to exist; everything was private. Cars, fences, large yards, all designed to ignore the neighbors right next to you. If you want a public realm, you have TV (and, now, reality TV). We drive out of our parking garages after spending an entire day in a cubicle staring at a computer, drive home surrounded by other people but entirely alone, drive into our attached garages and sit down in our TV rooms and stare at another glowing screen until it is time for bed. Then we get up the next morning and do it again. Is that really the American dream?

Kunstler writes in his book-ending Credo;

"We will have to replace a destructive economy of mindless expansion with one that consciously respects earthy limits and human scale. To begin doing that, we'll have to reevaluate some sacred ideas about ourselves. We'll have to give up our fetish for extreme individualism and rediscover public life. In doing so, we will surely rediscover public manners and some notion of the common good. We will have to tell people, in some instances, what they can and cannot do with their land. We will have to downscale our gigantic enterprises and institutions - corporations, governments, banks, schools, hospitals, markets, farms - and learn to live locally, hence responsibly. We will have to drive less and create public transportation that people want to use. We will have to produce less garbage (including pollution) and consume less fossil fuel. We will have to reacquire the lost art of civic planning and redesign our rules for building. If we can do these things, we may be able to recreate a nation of places worth caring about, places of enduring quality and memorable character." -

Kunstler hates suburbia, sprawl, and corporate control, and champions well-planned cities and towns, public space, and democracy. The Geography of Nowhere is a satisfying read because he is able to explain the causes of our offensive landscapes and explain why it is that we are (or should) be repulsed by them. While Kunstler is able to articulate the need for more humane communities, he ultimately puts too much faith in certain “new urbanism” developments to re-design them. It appears he revisits this in his sequel, Home from Nowhere, which is on my bookshelf, waiting to be read. I read this book as I was beginning my degree in community development at a college of urban planning and policy. It was a helpful book to lay out both some of the failures as well as the progressive renaissance in urban planning as I was embarking into that field. Kunstler's language is both biting and playful, seldom academic, and therefore recommended for a wide audience of anyone who pays attention to their environment. I should also mention that much of his book is a look at small town development and its problems, though my review will focus on urban areas. The review below was published in another form in my friend's zine. Let me know if you're interested, and I'll find you a copy.

Kunstler's thesis is simple, but not simplistic: over the last century, the automobile has been a primary engine for development, and in the process, has ruined our surroundings. Auto-led development has destroyed some of our greatest communities and has replaced them with dehumanizing places.

Kunstler’s task is to trace historically how our cultural and physical environments have degraded one another, facilitated by the automobile. The rise of the automobile simultaneously contributed to our ongoing ideological project of privatization as well as our physical pattern of expansionist growth (often for its own sake). These patterns have long histories in our civilization, dating to our colonial-era seizure of North America. Land distribution, from the start, was speculative, meaning that a large tract was bought by one party and divided and sold at a profit to many other parties. This practices “degrades the notion of the public realm,” (27) because there is no incentive for collective ownership, and consequently no collective use. The physical and cultural meet if we are to agree with Kunstler that the public realm is the manifestation of the common good. This is a basic premise for all of Kunstler’s analyses. The pattern of expansionist growth, of course, is deeply rooted in our society, stemming from the “manifest destiny” ideology of our western-moving colonizing project.

Because I’m interested in Chicago, Kunstler’s discussion of cities is most important to me. He argues that the automobile simultaneously destroyed city transit and enabled two waves of class flight to the suburbs. How did the automobile rise to such a position of power? Beginning in the 20s, General Motors (GM) began to purchase electric streetcar lines, tear out tracks, and convert them to bus routes. The electric streetcar was a relatively new invention, and in its short time operated as a clean, efficient, and inexpensive mode of mass transit. But GM removed streetcar tracks, thereby creating a demand for buses, as well as a need for space to accommodate the car boom that soon followed. Along with Standard Oil and Firestone Tire and Rubber, GM created various subsidiaries in order to systematically dismantle all electric transit. They succeeded, because by 1950, more than 100 electric-run trolley systems were replaced by gasoline-powered buses (92). More importantly, this process facilitated the privatization of transportation: with the trolleys gone, there was more room personal car use. Furthermore, cities suffered severely in order to accommodate the personal car boom: Between 1910 and 1940 Chicago spent $340 million on street widening. There is a class element to this as well, given that the poor who could not afford cars subsidized those who could, by paying taxes (the car is a private vehicle, but which travels over public space) (90). Other losses were priceless: highway construction, part of the shameful era known as urban renewal, leveled entire neighborhoods and displaced thousands, which in Chicago usually meant poor communities of color.

One reason cities bent to the will of the auto-related industries, is because auto-related industries, were, essentially the economy during Great Depression. The car, and the public infrastructure needed to support it, created jobs, and highway construction stimulated real estate growth.

Of course, Kunstler takes on the suburbs. He really hates post 50's suburbia, and his emotions serve as strong propellers for a sound analysis. The automobile, through highways, led people and development further from city cores. Highways themselves became sites for development, giving new markets in transit. Hence the cheaply constructed and utilitarian commercial buildings that pepper any intercity road systems: gas stations, convenience stores, fast food joints, etc. However, the characteristics of these developments, namely (1) Extreme separation of uses and (2) Large distances between them, are also part of the intrasuburban developments,. In other words, commercial, residential, industrial, and civic developments are isolated at great distances from one another. Separation of zoning uses originates from a good cause: keeping industry away from homes. However, Kunstler argues that post-war suburbs take this to an extreme, to the point where it is difficult to survive in the suburbs without a personal car.

Extreme separation of uses means that: “there are no corner stores in housing subdivisions, though the lack of them is a great inconvenience to anyone who would like to buy a morning newspaper or a quart of milk without driving across town. The separation of uses is also the reason why there are no apartments over the stores in the thousands of big and little shopping centers built since 1945, though our society desperately needs cheap, decent housing for those who are not rich” (177).

Kunstler determines that the separation of uses and large distances degrade the quality of building construction. Unlike a traditional mainstreet, on which people walk and experience commercial buildings on a “humans scale,” suburban developments in their ubiquitous malls, are experienced on a larger scale, via the automobile. Because suburban commercial developments are isolated malls, their architecture has no context within which to fit. The result that Kunstler calls “obscene,” “irreverent,” and “cartoonish.” A degradation in the design of spaces corresponds with a degradation in their use. We do not experience such places as a coherent part of our community; rather; we transport ourselves to them at intervals to satisfy our individual consumption needs.

A perfect example of how a degraded physical environment degrades our cultural environment is the mall. Effectively, the mall commercializes the public realm for the quintessential privatized suburb. In a mall, you may meet and engage with fellow citizens and strangers, but within constraints: security forces prohibit you from being there during certain hours, and from engaging in certain activities (exercising your freedom of speech, etc.).

Basic public amenities, such as sidewalks, are conspicuously lacking in many suburban developments, despite the real estate-promoted myth that suburbs are the best places to raise children. Indeed, the auto-driven developments of suburbs can be hostile to the rearing of children. An example is the fact that streets are made to accommodate the protection of cars (property) over pedestrians (people): trees are sometimes prohibited within certain footage of the street, because they would damage a car that has come off the road, despite the fact that trees might protect a pedestrian from the reckless vehicle.

A fascinating part of Kunstler's work is his reading of some of America's tourist places. I will refrain from spoiling Kunstler's descriptions of Disney World, which are uncompromisingly critical and hilarious. He also examines Henry Ford's Greenfield Village, a historical reconstruction of a town typical of the times of the famous industrialist's childhood. It is a place for Detroit residents to drive to, park their cars outside, and experience life as we imagine it to have been in the 1880s. Disney World, Greenfield Village, and other tourist places are alluring to us because they offer spaces of fantasy; an escape from everyday life. Kunstler argues that one important way that these places are fantastic is because there is no hint of the car, nor car-oriented space. The supreme irony, is of course, that Henry Ford, perhaps the individual most associated with the car, created a tourist place that is fantastic and wonderful for its reconstructed pre-automobile state.

So, can we ever overthrow the car and reject our history of whack urban planning? Kunstler answers that it's not a question of can, but when. -

How did many of our American cities evolve into the mess they are in? Kunstler does an excellent job of covering this up until the publication date of this book 25 years ago. The growth of the original suburbs based on trolley and rail travel, their evolution into the motor car suburb and the deliberate destruction of mass transit by the automotive and petroleum related industries as well as the actions of corrupt public officials.

One such official was

Robert Moses, who managed to create an agency in New York state that he ran without oversight except for a board that he selected and appointed. A new low in corruption, continuing the fine Tammany Hall tradition of massive corruption. He hated transit of all kinds, designing highway overpasses too low for buses, refusing any access for rail or trolley and anything else that could supplant the car.

At the same time many towns and cities were outlawing mixed use, i.e. housing over store fronts as well as other zoning laws that forced separation of work and the classes. Many of these new developments blocked people of color from living in them, so there was a strong racist component to this form of civic planning. You can read

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America for further details on this.

Add to that the Brutalist/Modernist architecture movement which has spawned some of the ugliest and least livable buildings in our cities. One example that I am personally familiar with is one section of old downtown Long Beach that was declared blighted by the city and redeveloped. Prior to this it was a collection of modest 1,2, and 3 story buildings from the 1910s and 20s that housed a variety of unique small businesses and residences including Marmion Paper that sold spices in any amount and would then wrap them in paper, they hadn't changed since the 30s. The city redid this area twice, the first time with the "ghost mall", my favorite mall for Xmas shopping and the second time they attempted to add housing and recently wandering the area via google after twenty plus years they have partially succeeded. Still looks pretty dead though!

The author then describes three cities, Portland OR, Detroit and Los Angeles wondering how they will evolve. In the case of Portland, pretty well. Detroit... read

A $500 House in Detroit: Rebuilding an Abandoned Home and an American City or

Detroit: An American Autopsy. Los Angeles, still a mess but getting a little better? The California state master development plan has helped with reining in the potential sprawl of America's premier auto megalopolis.

There's a section on amusement parks/areas that include Disney, Atlantic City and Woodstock, VA. The roasting he gives Disney and the failed Trump Atlantic City casino is amusing and I feel a bit of sadness for Woodstock turning into a little tourist trap.

Then there's a final section on current (1993) developments that show promise, many of which are still going well, (I want his crystal ball!) as well as a plug for one of my favorite architects,

Christopher W. Alexander, author of "A Pattern Language" among other works.

An outstanding retrospective only marred by its age, if he updated this book or wrote a new one covering the last 25 years, I would read it in a heartbeat. He does have some slightly more current books on the subject and an active blog so it looks like more books for the to read list. -

Despite the fact that the author is a grumpy borderline misanthrope, he does raise a ton of good points in this book about the unnatural development of suburban sprawl in the United States. Reading it felt enlightening in ways, pointing out things that have always bothered me about our current environment that I haven't quite processed at a conscious level. As a historical piece, this reads smoothly. However, I couldn't help but get more and more annoyed at the author as the book went on. He romanticizes a past that he never lived in and my guess is that if he did actually live in it he would find just as much or perhaps even more to complain about.

-

Very interesting and insightful. Some chapters didn’t feel particularly necessary, but I enjoyed the overall thrust of the book. I’d love for there to be a revised edition someday. So much has changed since this book came out, and at the same time so much has stayed the same.

-

Really enjoyed this. Like Wendell Berry in many ways...but non-religious, more snarky, more pro-city, and more focused on the built environment rather than nature. Would recommend.

-

I'll start with the good.

New Urbanism! The hope of the suburban hopeless! For anyone who ever looked at a freeway interchange, a modern office park, or a cookie cutter subdivision and thought "gee, this place is pretty depressing." Here is a book, written in 1993, that not only confirms your suspicion but gives a laundry list of reasons why. I had always assumed in a vague way that it was the model houses to blame... you could only choose between 3 or 4 models and thus were virtually indistinguishable from your neighbor. But there's so much more. Home design, lot size, placement of the home on the lot, the arrangements of the lots in relation to the street, the street shape, the proximity to public areas, and many more principles are enshrined in zoning laws which conspire against the suburbanite. The solution lies in better zoning, planned neighborhoods that are true communities with walkable errands, a diverse population, a sense of purpose, and architectural unity. Five stars.

Unfortunately, Kunstler is a top notch asshole. After a few pages of reading I thought "what is WITH this guy?" and did a bit of Googling. Check out his website sometime. He is a self-styled prophet of doom who clearly enjoys fear-mongering and provocation. His resume of failed apocalyptic forecasts is impressive. In case you needed further convincing, his lone writing credential in this book is that he was an editor at Rolling Stone, which should tell you all you need to know about his commitment to journalistic excellence. One star.

Because of this... "writing style" ...it isn't worth listing and refuting all the points in his book that are questionable or flat out wrong. But there are some things worth summarizing for their entertainment value. Among the things Kunstler hates: plastic signage, chain stores, freeways, casinos, skyscrapers, anything designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, buildings with siding, buildings with flat roofs, Disney World, television, Cheetos, Puritan colonists, Southern plantation colonists, the Industrial Revolution, scientific progress, Detroit, Los Angeles, Modernism, and cars. Boy, does he really hate cars. Cars are the cause of all the things listed above, as well as child abuse, alcoholism, and teen pregnancy. Cars haven't just made us lazy, they've put us on a one-way track to a post-apocalyptic, medieval lifestyle when the oil runs out. (Recall he hates scientific progress, so any hope of alternative technologies is a lost cause.)

So focused is his rage toward cars that during a visit to Greenfield Village (an outdoor museum of famous American buildings from yesteryear outside of Detroit), he quizzes other patrons on why they find the place so agreeable, hoping to get them to answer that there are No Cars. The people give a myriad of thoughtful answers - the grounds are well kept, the employees friendly, the exhibits interesting, etc. Unable to coax the No Cars answer out of anyone (after all, isn't this how good journalism works?) he expresses with great disappointment and resignation that the people he spoke with are just plain stupid (his word).

Equally intense is his distaste for Disney World, filled with its fake scenery, worship of death and consumerism, blah blah. Dude, its a fucking amusement park. You can just imagine him knocking on a rocky butte in Frontierland and exclaiming "why this isn't real at all!!!! This is a shocking scandal of illusion!!!" Yeah Grandpa, it is. Can you hold my purse while I ride Space Mountain?

But I get what he's saying underneath, and for the most part, I agree. I just hope I never have to meet the guy. Looks like I'll be turning to other texts on the topics of building better living places, although surely GofN was ground-breaking when it first came out. Wikipedia claims it is standard reading now in many architecture and planning courses. Wikipedia also uses a photo from Celebration, Florida as the model of New Urbanism development. Celebration of course was designed and built by Kunstler's favorite... Disney! I bet that really sticks in his craw :)