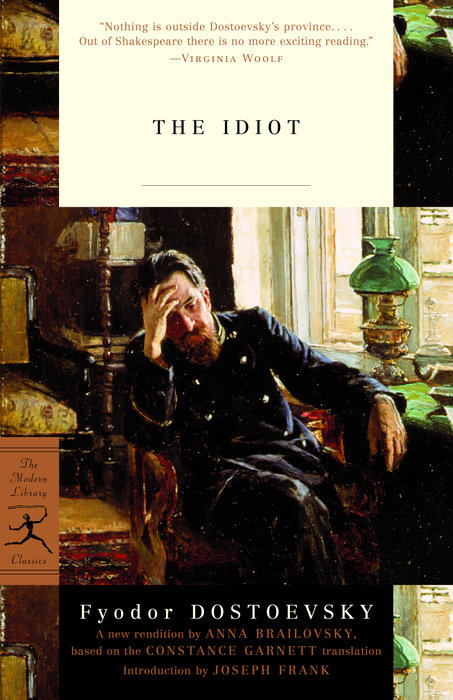

| Title | : | The Idiot |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0679642420 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780679642428 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 667 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1869 |

The Idiot Reviews

-

If Raskolnikov was the charismatic murderer whose side I took despite myself when he killed an old woman out of greed and broke down psychologically afterwards, Prince Myshkin is the supposedly good, childlike Christ figure whom I failed to like at all.

Just do make it clear from the beginning: I liked the novel just as much as

Crime and Punishment and

Notes from Underground, and I found it just as compulsively readable. The cast of characters is magnificent.

My sole problem is the character of Myshkin. We are not a likely pair to hit it off, of course.

He is a religious fanatic, whose conviction is so narrow-minded that he hates other variations of Christian dogma even more than atheists: “Yes, that’s my opinion! Atheism only preaches a negation, but Catholicism goes further: it preaches a distorted Christ, a Christ calumniated and defamed by themselves, the opposite of Christ! It preaches the Antichrist, I declare it does, I assure you it does!” - I am an atheist, but strongly in support of tolerance and respect beyond the narrow boundaries of one’s own convictions. So I will give Myshkin a pass on his fanaticism, knowing full well he wouldn’t give me one, considering his reaction when he heard his benefactor had converted to Catholicism.

He is a Russian nationalist, believing in expanding Russian dogma to the West: “Not letting ourselves be slavishly caught by the wiles of the Jesuits, but carrying our Russian civilisation to them, we ought to stand before them and not let it be said among us, as it was just now, that their preaching is skilful.” - I believe in global citizenship and consider nationalism to be the greatest evil in world history. But I will give him a pass on that one, knowing the historical framework in which it was uttered.

He is proud of his lack of education, and does absolutely nothing to enhance his own understanding, despite having leisure to spend all day studying. I believe in lifelong learning to develop as a human being. But I will give him a pass on that one, knowing he suffers from epilepsy and maybe from other conditions as well, which might make learning impossible for him.

He is an elitist, openly rejecting equality and democracy in favour of his own, idle class: “I am a prince myself, of ancient family, and I am sitting with princes. I speak to save us all, that our class may not be vanishing in vain; in darkness, without realising anything, abusing everything, and losing everything. Why disappear and make way for others when we might remain in advance and be the leaders?” - I am for equality and democracy, for a classless society without any privileges.

He is utterly afraid of female sexuality and almost pathological in his attempt to ignore the fact that it exists, admiring childlike behaviour and the inexperienced beauty of virgins. - I am a grown-up woman.

I will let all of that pass, there is no reason why I shouldn’t be able to identify with that as much as with a raving murderer, right? What I can’t accept is his posturing as a “truly good”, almost holy person. That is too much. His social ineptitude, his lack of imagination, his literal-mindedness, his prejudices - all of that might be fitting the time and place where he lives, but it is not objectively good.

In fact, I don’t see any goodness in him at all. Even Raskolnikov, poor, and under supreme stress, was able to spontaneously give his last money to a desperate family to finance a funeral. Myshkin does nothing helpful with his fortune, which conveniently fell into his over-privileged lap. On the contrary. He uses the money to cruise in the Russian upper class society and to mingle with distinguished families. He doesn’t work, and isn’t even remotely interested in anything to do with actual progress in society.

Instead, he gives credit to whoever happens to be in the room with him at the moment, without engaging or giving any active help, and he changes his mind when another person steps into the room. Critics are eager to call this his “innocence” and gullibility, and to use it as proof that he is a “better person” than the characters who have motives and agendas for their actions. Since when is cluelessness a virtue? And what if he is not an idiot? If you for one second step out of that thought pattern, you can also call his change of mind hypocrisy, or opportunism, or fear of conflict, or flattery.

Some might call it Christian meekness. I call it condescension. Myshkin is incredibly one-dimensional in his value system, fearing sexuality and human interaction. To compensate for his fears, he puts himself “above” them, looking down on “weak” people, forgiving and pitying them. But what right has he to “forgive” other people for engaging in conflicts that are caused by his own social ineptitude? If I could see in Myshkin a person who is on the autistic spectrum, I would feel compassion for him and be frustrated that his community is not capable of helping him communicate according to his abilities. But whenever that idea comes to mind, the big DOSTOYEVSKY LITERARY CRITICISM stands in the way. Under no circumstances am I to forget that Dostoyevsky truly saw in Myshkin a Christlike figure, and that he himself was committed to orthodox Christian dogma to the point of writing in a letter (in 1854):

“If someone proved to me that Christ was outside the truth, and it was really true that the truth was outside Christ, then I would still prefer to remain with Christ than with truth.”

Well, to be honest, I think that is precisely what this novel shows. Dostoyevsky, the brilliant realist writer, writes a story containing the truth of social life as he has accurately observed it, and his Christ is moping around on the fringes, causing trouble rather than offering ethical guidelines. He is absolutely passive, incapable of one single motivated, proactive good deed.

Only criminals and ignorant peasants invoke the name of Christ in the novel. The educated people with whom Myshkin mingles are concerned with their own nervous modernity. They act like neglected children, drawing negative attention to themselves to make the (God)-father figure notice them. But he remains silent, ignoring even his most cherished child, the one he sacrificed for all the others, - Christ. It is Holbein’s dead Christ, brutally shown in his human insignificance, that stands as a symbol for the religious vacuum in the novel, a Christ figure that can make people lose their faith, as Myshkin admits himself.

The characters argue and discuss their respective positions on philosophy and religion throughout the long digressive plot, and Myshkin mourns earlier times when people were of a simpler mind:

“In those days, they were men of one idea, but now we are more nervous, more developed, more sensitive; men capable of two or three ideas at once … Modern men are broader-minded - and I swear that this prevents their being so all-of-a-piece as they were in those days.”

That is what he says to Ippolyt, a poor, cynical 18-year-old boy dying (but not fast enough) of consumption. When the young man asks Myshkin how to die with decency, the idiotic Christ figure doesn’t offer him his house or moral support, even though he knows that Ippolyt is in a conflict with Ganya, with whom he is currently staying. No, help can’t be offered, just this:

“Pass us by, and forgive us our happiness”, said Myshkin in a low voice.”

Oh, the goodness of that (non-)action.

Another telling situation occurs when Myshkin receives the clearly confused general Ivolgin, in a state of rage, whose Münchhausen-stories of meeting Napoleon are evidently hysterical lies. Even the idiotic Myshkin understands that something is wrong with the general, but he lets him rave on, encouraging him in his folly. If that was all, I could argue that two fools had met, and that Myshkin couldn’t be expected to show compassion and try to calm down the ill man (who has a stroke in the street shortly afterwards, supported by the “malignant” atheists rather than the Christian elitist characters). But Myshkin is not a fool in that respect, just a passively condescending man. His reaction is outrageous:

“Haven’t I made it worse by leading him on to such flights?” Myshkin wondered uneasily, and suddenly he could not restrain himself, and laughed violently for ten minutes. He was nearly beginning to reproach himself for his laughter, but at once realised that he had nothing to reproach himself with, since he had an infinite pity for the general.”

Right! How convenient for you, Prince! And you suffer so much when others laugh at your inadequacies. I have an infinite pity for you, Sir! But I won’t raise a finger to help you, all the same. Because being a completely innocent little idiot, I don’t know how to do that.

Which leads me to my last comment on the character of Myshkin, who repeatedly was compared to Don Quixote in the novel. He is NOT AT ALL LIKE THE DON!

Don Quixote has more imagination and erudition than his contemporaries. Myshkin has none at all.

Don Quixote actively wants to change the world for the better. Myshkin wants to passively enjoy his privileged status.

Don Quixote is generous and open-minded. Myshkin is aloof and uninterested.

Don Quixote has a mission. Myshkin floats in upper class meaninglessness.

Don Quixote loves his ugly Dulcinea. Myshkin can’t choose between the two prettiest girls in society, but wants them to remain children to be able to worship them as virgins.

So, who were my favourite characters then? As often happens to me while reading Dickens as well, I found much more satisfaction following the minor characters. Kolya, Ippolyt, Lebedyev, Rogozhin, Aglaia, Nastasya - all these people experiencing Russian society in the process of moving towards modernity are affected by one or several of its aspects. They try to deal with modernity ad hoc, without a recipe, and suffer from confusion.

Aglaia!

When she says she wants to become an educator, to DO something, she shows the spirit of future entrepreneurship, including women in active life. When she goes from one emotional state to another, not willing to be a negotiable good in her parents’ marriage plans, a piece of property moving from one domestic jail to another, she is a true hero. But she embraces the idea of ownership and control, and in order to own Myshkin, she acts out a despicably arrogant farce in front of a vulnerable rival, using as a weapon her privilege and chastity. A flawed but interesting character for sure. She would have been utterly unhappy, had she reached her goal.

Kolya!

Trying to navigate his hysterical environment and to build bridges between his family’s needs and the society they depend on, and to support parents, siblings, and friends with actions rather than words, he is a truly good person.

Rogozhin!

Blinded by passion but capable of sincere feeling and fidelity, he is a true lover, yet driven to madness and criminal behaviour. He admits to his crimes and accepts the following punishment.

Nastasya!

The abused child who takes out the punishment on herself, like anorexic or self-harming young girls nowadays, convinced that the harm done to them is a sign of their own filthiness. Myshkin drives her over the edge with his condescending pity and forgiveness - by enforcing her idea of guilt and worthlessness. As if Myshkin had any right to claim superiority! He seals her fate when he remains completely passive in the showdown between her and arrogant, impertinent Aglaia, and then creates an atmosphere of self-sacrifice during the wedding preparations:

“He seemed really to look on his marriage as some insignificant formality, he held his own future so cheap.”

So what am I to make of my reading of the Idiot? What is the ultimate feeling, closing the book after days of frenzied engagement with the characters?

I loved the novel, hated the main character (but I’ll FORGIVE him, of course, feeling PITY for his suffering), and am prepared for another Dostoyevsky. Let the Devils haunt me next! -

I’ve been trying to review this book for over a week now, but I can’t. I’m struggling with something: How do I review a Russian literature classic? Better yet, how do I review a Russian literature classic without sounding like a total dumbass? (Hint: It’s probably not going to happen.)

First I suppose a short plot synopsis should be in order:

The Idiot portrays young, childlike Prince Myshkin, who returns to his native Russia to seek out distant relatives after he has spent several years in a Swiss sanatorium. While on the train to Russia, he meets and befriends a man of dubious character called Rogozhin. Rogozhin is unhealthily obsessed with the mysterious beauty, Nastasya Filippovna to the point where the reader just knows nothing good will come of it. Of course the prince gets caught up with Rogozhin, Filippovna, and the society around them.

The only other Dostoevsky novel I’ve read was Crime and Punishment, so of course my brain is going to compare the two. Where Crime and Punishment deals with Raskolnikov’s internal struggle, The Idiot deals with Prince Myshkin’s effect on the society he finds himself a part of. And what a money-hungry, power-hungry, cold and manipulative society it is.

I admit that in the beginning and throughout much of the novel I felt intensely protective of Prince Myshkin. I got pissed off when people would laugh at him or call him an idiot. Then towards the end of the novel, I even ended up calling him an idiot a few times. Out loud. One time I actually said “Oh, you are an idiot!” But then I felt bad.

Poor Prince Myshkin. I think he was simply too good and too naïve for the world around him.

Now here is where my thought process starts to fall apart. There’s just so much to write about that I can’t even begin to write anything. There were so many themes that were explored in the novel such as nihilism, Christ as man rather than deity, losing one’s faith, and capital punishment among other things. And I haven’t even mentioned Dostoevsky’s peripheral characters yet, which, like those in Crime and Punishment, are at least as interesting, if not more interesting than the main characters. My favorite character was Aglaya Ivanovna. She was so conflicted with regard to her feelings about the prince and loved him in spite of herself. I had mixed feelings toward Ganya. I mostly disliked him, but I grew to like him more towards the end. The entire novel was much like a soap opera, but a good soap opera, if that makes sense.

Well, at this point I’ve been moving paragraphs around for far too long, and I realize there’s no way this review will do the book any justice. I wanted to write about the symbolism of the Holbein painting and how I love that in both Dostoevsky books I've read he references dreams the characters have, but I just have too many questions and not enough answers. Instead I'll just say that it was truly an excellent read and definitely worth your time. -

Prince Lev Nicolayevich Myschkin discovered relativity in 1886.

Well, actually the scientific theory of relativity wasn’t discovered until 30 years later, by Albert Einstein, but I don’t think that discovery would have been possible without the relativistic ferment that had started sweeping through Europe in the mid-19th century, with its ultimate CHRISTIAN formulation in The Idiot, in 1886.

Moral chaos is so cataclysmic to conservative spectators. So much so to Prince Myschkin, in fact, that he suffers an enormous three-year nervous collapse. But he comes out of it Reborn.

“Reborn!?” you may say. “Isn’t he just... a little ODD?”

Well listen, if as an intelligent kid you were submitting - along with the rest of intelligent Europe - to the Willy-nilly Transvaluation of all Values, wouldn’t you want to somehow return to your Moral Roots?

And if you didn’t Pooh-Pooh change in any form, like so many mature people do, wouldn’t you try to reason through this enormous alteration in values?

Prince Myschkin does both. He REASONS THROUGH THE CLIMACTERIC OF RADICAL RE-ORIENTATION - from a CHRISTIAN POV.

Something we all should be doing today if we’re believers.

Sure, the sophisticated St Petersburg in-set decides mainly to lead him on - apparent imbecile that he is - into traps of their own devising, but isn’t that what most normal people do today with an oddball: feed him enough rope to hang himself with?

But these worldly sophisticates have a “don’t go there” mindset to new ideas. Unless they’re new FUN ideas. They are intellectually and morally stuck. And so the nutty prince is like a breath of fresh air to them, in a funny sort of way!

Bigotry wasn’t born yesterday. It was born when someone decided to take a small, SAFE pathway through the perils of life. And so many have - alas! - followed him.

But Prince Myschkin has just emerged, barely breathing, from a total moral collapse in a world of ethical relativism. More power to him, I say - at least he’s not scared of the world’s shadows anymore.

For he’s now emerged with a triumphant Christian Faith from the dark chambers of Dis. Into a New, Wide-Awake World.

Myschkin, you see, refuses to JUDGE OTHERS. All his crazy antics are just a logical offshoot of that logically primitive decision.

The basic building block of his, and all true ethical behaviour.

And that’s what makes this book Great.

For this is the portrait of an unlikely modern saint - but it is written with a double-edged pen!

It’s ironical - and it’s not.

Sort of reminds you of the Gospel, doesn’t it?

And, somehow, you know - I think that’s what Dostoevsky intended. -

There are many reviews of this book making out that Prince Myshkin was Christ-like, a truly good man who lived for the moment. A holy idiot, or more accurately, wholly idiot indeed is what he really was. Why did they think Dostoyevsky entitled the book, The Idiot if he meant 'The Man who was Innocent and Really Good" or "The Man who was like Jesus"? The title wasn't any kind of irony, it was about an idiot.

Prince Myshkin had spent years in a sanitarium for his epilepsy and returns to Russia where he trusts untrustworthy people, falls for all their plots where he is the patsy, and falls in love with a rather uppity girl who returns his affections and then when it comes to the moment, chooses another woman for all the wrong reasons and thereby ends up rejected by both.

He is the very definition of an idiot, he never, ever learns and what intelligence he has he doesn't put to working out the truth of a situation and what he should do to benefit himself. He always falls for the next plot, the next plan, the next person with a glint in their eye for how they can use him to further their own ends. And he goes just like a lamb to the slaughter.

Sadly, the debacle, written in a time when not even the word 'neurology' had been invented, let alone the science, is rather idiotic. On getting drawn into a crime committed by a man mad in every sense, crazy and angry, his epilepsy degenerates into a mental illness so deep he crosses over into another land. Bye bye gentle idiot. I was glad to read of you, I'm glad I didn't know you. -

(Book 861 From 1001 books) - Идиот = The Idiot, Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Idiot is a novel by the 19th-century Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky. It was first published serially in the journal The Russian Messenger in 1868–9.

The title is an ironic reference to the central character of the novel, Prince (Knyaz) Lev Nikolaevich Myshkin, a young man whose goodness and open-hearted simplicity lead many of the more worldly characters he encounters to mistakenly assume that he lacks intelligence and insight.

In the character of Prince Myshkin, Dostoevsky set himself the task of depicting "the positively good and beautiful man".

The novel examines the consequences of placing such a unique individual at the center of the conflicts, desires, passions and egoism of worldly society, both for the man himself and for those with whom he becomes involved.

The result, according to philosopher A.C. Grayling, is "one of the most excoriating, compelling and remarkable books ever written; and without question one of the greatest."

تاریخ نخستین خوانش در سال 1974میلادی

عنوان: ابله؛ نویسنده: فئودور داستایوسکی؛ مترجم: مشفق همدانی؛ تهران، کتابهای جبیی، 1341؛ در چهار جلد؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، صفیعلیشاه، چاپ سوم سال 1348؛ در چهار جلد؛ چاپ پنجم 1356؛ چاپ دیگر 1362؛ چاپ بعدی 1366؛ چاپ دیگر 1396، در دو جلد؛ شابک 9789645626929؛ تهران، امیرکبیر، چاپ سوم 1393؛ در سه جلد؛ شابک 9789640015896؛ موضوع: داستانهای نویسندگان روسیه - سده 19م

عنوان: ابله؛ نویسنده: فئودور داستایوسکی؛ مترجم: سروش حبیبی؛ تهران، چشمه، 1383؛ چاپ سوم 1385؛ چهارم 1386؛ ششم 1378؛ هفتم 1388؛چاپ هشتم 1389؛ چاپ نهم 1390؛ در 1019ص؛ چاپ یازدهم 1393؛ شابک 9789643622114؛

مترجم: منوچهر بیگدلی خمسه؛ تهران، ارسطو، 1362؛ در دو جلد؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، گلشائی؛ 1368؛ در دو جلد؛ تهران، نگارستان کتاب؛ 1387؛ در دو جلد؛ شابک 9789648155839؛

مترجم: نسرین مجیدی؛ تهران، روزگار، 1389؛ در 920ص؛ شابک 9789643742768؛

مترجم: کیومرث پارسای؛ تهران، سمیر، چاپ چهارم 1395؛ در 640ص؛ شابک 9789642200986؛

مترجم: آرا جواهری؛ تهران، یاقوت کویر، 1395؛ در دو جلد؛ شابک 9786008191063؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، پارمیس؛ 1392؛ در دو جلد؛ شابک 9786006027623؛ چاپ دیگر 1396؛ در 826ص؛ شابک 9786008708094؛

مترجم: اصغر اندرودی؛ تهران، ناژ؛ 1394؛ در دو جلد؛ شابک 9786006110158؛

مترجم: پرویز شهدی؛ نشر به سخن، 1396؛ در دو جلد؛ شابک 9786007987407؛

مترجم: میروحید ذنوبی؛ تهران، آهنگ فردا، 1396؛ در 838ص؛ شابک 9786007383728؛

مترجم: امیر رمزی؛ تهران، آریاسان، 1396؛ در 838ص؛ شابک 9786008193760؛

مترجم: آرزو خلجی مقیم؛ تهران، نیک فرجام، 1395، در 784ص؛ شابک 9786007159316؛ چاپ دیگر 1396؛ در 838ص؛ شابک 9786007159514؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، سپهر ادب، 1395؛ شابک 9789649923963؛ در دو جلد؛

مترجم: مهری آهی؛ تهران، خوارزمی؛ 1395؛ در 1075ص؛ شابک 9789644871566؛

مترجم: عباس سبحانی فر؛ تهران، آنیسا، 1396؛ در 839ص؛ شابک 9786008399728؛

مترجم: علی صحرایی؛ تهران، ابر سفید، 1392؛ در 536ص؛ شابک 9786006988085؛

پرنس «میشکین»، آخرین فرزند یک خاندان بزرگ ورشکسته، پس از اقامتی طولانی در «سوئیس»، برای معالجه ی بیماری، به میهن خویش بازمیگردد؛ بیماری او، رسماً افسردگی عصبی است، ولی در واقع «میشکین»، دچار نوعی جنون شده، که نمود آن بیارادگی مطلق است؛ افزون بر این، بی تجربگی کامل او در زندگی، اعتماد بیحدش نسبت به دیگران را، در وی پدید میآورد؛ «میشکین»، در پرتو وجود «روگوژین»، همسفر خویش، فرصت مییابد که نشان دهد، برای مردمان نیک، در تماس با واقعیت، چه ممکن است پیش آید؛ «روگوژین» این جوان گرم و روباز و با اراده، به سابقه ی هم حسی باطنی، و نیاز به ابراز مکنونات پیشین، در راه سفر، سفره ی دل خود را، پیش «میشکین»، که از نظر روحی نقطه مقابل اوست، میگشاید؛ «روگوژین» برای او، عشقی را، که نسبت به «ناستازیا فیلیپونیا»، احساس میکند، بازمیگوید؛ آن زن زیبا، که از نظر حسن شهرت، وضعیت مبهمی دارد، به انگیزه ی وظیفه شناسی، نه بی اکراه، معشوقه ی ولی نعمت خود میشود، تا از آن راه حق شناسی خود را، به او نشان دهد؛ وی، که طبعاً مهربان و بزرگوار است، نسبت به مردان، و به طور کلی نسبت به همه کسانیکه سرنوشت با آنان بیشتر یار بوده، و به نظر میآید که برای خوار ساختن اوست، که به برتری خویش مینازند، نفرتی در جان نهفته دارد؛ این دو تازه دوست، چون به «سن پترزبورگ» میرسند، از یکدیگر جدا میشوند، و پرنس نزد ژنرال «اپانچین»، یکی از خویشاوندانش، میرود، به این امید که برای زندگی فعالی که میخواهد آغاز کند، او پشتیبانش باشد، و رخدادهای دیگر…؛

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 06/06/1399هجری خورشیدی؛ 13/05/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

Prince Myshkin (whose name to the Russian ear sounds somewhat like Prince Mousy) may be considered as a disciple of quietism…

“Oh, so you are a philosopher; but are you aware of any talents, of any ability whatever in yourself, of any sort by which you can earn your living? Excuse me again.”

“Oh, please don’t apologise. No, I fancy I’ve no talents or special abilities; quite the contrary in fact, for I am an invalid and have not had a systematic education. As to my living, I fancy...”

But those who always turn the other cheek to those who slap them on the right cheek get themselves eventually broken by evil and drowned in the stream of malice.

And a man capable of doing nothing but good and longing for the union with God is awarded with a title The Idiot and crucified – and the crowd rejoices. -

„- Dar Rogojin s-ar căsători [cu Nastasia Filippovna]?

- Cred că și mîine s-ar putea căsători [zise Prințul]; s-ar căsători și, peste o săptămînă, zic eu, ar înjunghia-o” (p.40).

Prințul Mișkin are toate calitățile unui om „cu desăvîrșire minunat”: inocență, franchețe, intuiție a psihologiei celor din jur, capacitate de a anticipa consecințele, bunătate, blîndețe. Din păcate, „clarviziunea” lui e luată de ceilalți în rîs. Sinceritatea lui necruțătoare îi aduce calificativul de „idiot”.

Termenul „idiot / idiota” nu a avut întotdeauna sensul peiorativ de azi. În Evul Mediu, îl desemna pe individul care nu a fost pervertit de școli și lecturi, individul care judecă și gîndește cu mintea lui. Cu acest sens, îl folosește Nikolaus Cusanus în titlurile cărților sale.

Firește, Lev Nikolaevici Mîșkin poate fi caracterizat ca „idiota” (în sens medieval). Dar în romanul lui Dostoievski, termenul e folosit, desigur, cu înțelesul lui difamant: Mișkin e prost, sărac cu duhul, nu știe să-și țină gura, nu respectă discreția, spune tot ce-i trece prin cap, indiferent de urmări. Franchețea lui nesăbuită este, de multe ori, o formă de cruzime. Din acest motiv, Ganea îl lovește, iar Rogojin vrea să-l ucidă. E o nouă ipostază a lui Don Quijote. Cînd oamenii s-au obișnuit cu minciuna și situațiile echivoce, adevărul devine o ofensă și un scandal. Prințul este cu siguranță un „trouble-fête”. După cum exclamă un personaj, „apariția lui produce haos”.

Am putea gîndi că prezența prințului va opri catastrofa din final. Dar nu este deloc așa. Mîșkin nu poate împiedica răul. Mai curînd, îl precipită...

Desigur, Dostoievski și-a pus în Idiotul o problemă mai largă, știm asta din însemnările lui. Oare ce s-ar întîmpla dacă Iisus Christos ar reveni printre noi? Întrebarea l-a obsedat pe autor multă vreme. Un prim răspuns poate fi găsit în romanul de față, celălalt în „Parabola Marelui Inchizitor” din Frații Karamazov. În ambele cazuri, a doua venire ar consemna un eșec. Omul nu mai poate fi salvat de nimeni, Dumnezeu a eșuat. Răspunsul lui Dostoievski e pesimist.

P. S. Cineva a rezumat Idiotul în chipul următor: „Doi bărbați iubesc aceeași femeie, în timp ce două femei iubesc același bărbat”. E imposibil să știm dacă Mîșkin o iubește cu adevărat pe Nastasia Filippovna. Mila nu înseamnă întotdeauna iubire.

P. P. S. Dostoievski a lucrat la Idiotul din decembrie 1867 (se afla în exil la Geneva) pînă în ianuarie 1869. Criticii literari nu au fost deloc entuziasmați de roman. L-au găsit haotic, rău construit, greu de urmărit. Meseria criticului literar e să caute noduri în papură și, cînd nu le găsește, să le inventeze... -

A terrific novel - very worth reading - but lacking the thrust and pleasures of BROTHERS KARAMAZOV, which is one of my favorite books. It is, perhaps, the most difficult novel to evaluate with the Goodreads star system, because it is both very, very great, and not particularly good.

When the action soars - in searing, autobiographical moments, with sequences of epilepsy, fits, executions, and long social sequences - there is really nothing like it. An outdoor party scene with the (overly) noble Prince Myshkin will stick with me forever, as will the cursed love between Nastasya Fillippovna and Rogozhin. The idea of a pure man misunderstood by an impure society is wonderful, but THE IDIOT reads more like a sequence of thematic parables than a novel.

I've been taught, and I teach, the iceberg theory of writing. The author should know more about her characters than she is willing to show (90% below water, 10% visible.) This iceberg is almost totally submerged. The main action - the stuff I was dying to see - too often occurred BETWEEN parts of the novel. I have never experienced such exciting exposition in my life - but I saw almost none of that excitement on the page. Structurally, this makes it somewhat disastrous, and it feels rushed, as if Dostoevsky was so eager to plumb the depth of philosophy that he forgot to provide us with a plot. This makes the book fascinating, but a very, very slow read. I am very grateful to have read it; I was rarely grateful to be reading it. -

رضا امیرخانی، جایی گفته بود که "اگه قرار بود نویسنده ها پیامبری داشته باشن، پیامبرشون تولستوی خواهد بود." حرف درستیه، ولی این پیامبر از داستایوسکی وحی دریافت میکنه!

من

از بین رمان های داستایوسکی، بیشتر از همه عاشق "جنایت و مکافات" و بعد "ابله" هستم. در درجات بعد، قمار باز و برادران کارامازوف و همزاد و...

یادم نمیره. تابستون، ماه رمضون، بعد از سحر تا نزدیکای ظهر بیدار میموندم و یه کله "ابله" میخوندم. واقعاً میخکوبم میکرد. همزمان مادرم هم میخوند و با هم راجع بهش صحبت میکردیم. تجربه ی مشترک خوبی بود.

این کتاب

ماجرای کلی رمان، راجع به پرنس میشکینه. پرنس میشکین انگار ناظر جهانه. مثل یه بچه، معصومه و به خاطر همین ناظر بی طرف و قابل اعتمادیه. در ابتدای داستان، چشم باز می کنه، دنیای سیاه و آشفته و غیر قابل درک ما رو می بینه و تلاشی هم برای اصلاحش میکنه، ولی موفق نمیشه. در انتهای داستان، انگار به خاطر رنجیدن از این همه زشتی، دوباره چشم می بنده و به دنیای پاک بی خبری بر می گرده.

دو نکته

اول این که

دوم این که شخصیت پرنس میشکین، که یه انسان ساده دله و در ابتدای داستان عکس آناستازیای زیبا و اغواگر

(femme fatale)

رو میبینه و توجهش به اون جلب میشه، تا حد زیادی شبیه شخصیت ساده دل کنستانتین لوی�� در "آنا کارنینا"ست که اون هم در اوایل داستان عکس این زن زیبا و اغواگر رو میبینه و شیفته ش میشه. چه بسا تولستوی از داستایوسکی تقلید کرده باشه. شاید هم نه. -

This guy is on a morning train to St Petersburg. He knows nobody there. He has no money and no possessions. He’s this close to being a vagabond. But he gets in conversation with this other guy and one meeting leads to another and by ten o’clock that night – 160 pages later – he is telling a lady he never met before not to marry a guy he never met before, and then declaring his own total love for this lady.

That’s right just another day in 19th century Russia, Dosto-style.

If Dostoyevsky was a 21st century writer he would be so rich writing scripts for shows like Desperate Housewives or Days of Our Lives because one thing he was was a natural born soap opera scriptwriter. He produced tremendous shouty thirty page arguments and 50 page carcrash scenes involving 12 outrageously-behaving borderline lunatics, just right for the campier type of tv, but I guess he’d have flounced out of his moneyspinning career on day one when they refused to include one character’s five minute monologue on what it must feel like in the half second when you are watching the guillotine blade begin to descend on your naked neck.

WHAT THIS LONG BOOK IS ABOUT

The Idiot is about this young Prince (it was a minor minor title, not royal or even royalish) who comes to town and gets involved with these train people and their families and kind of gets all entangled. There are two strong female leads (Nastasya and Aglaya), both of whom can bring men to their knees with a single glance, and this leads to many complications. Some of the plot can be summed up by the Lovin’ Spoonful in their 1966 hit “Did you Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?”

Did you ever have to finally decide?

And say yes to one and let the other one ride?

There's so many changes and tears you must hide.

Did you ever have to finally decide?

It may be a bit spoilerish (but you will have forgotten it before you get round to reading this) but these two women finally meet in a showdown that is a 19th century Russian version of the one in A Fistful of Dollars. It's a great scene, one of many.

Also, I should mention one great scene where Nastasya rips a whip out of some nasty guy's hands and smashes his face with it.... go Nastasya!!

DOSTOWORLD

Rich men who rape poor girls don’t generally apologise :

He could not repent of his original action with her as he was a hardened voluptuary

Guys have got poor attitudes to marriage :

Although at last, after agonising hesitations, he agreed to marry the “vile woman” he swore in his soul to take a bitter revenge on her for it and to “harry her to death” later on

People do not think tact is something to even think twice about:

Earlier today I thought you were an out-and-out evildoer… now I see that one can consider you neither an evildoer nor even a very corrupt man. In my opinion, you’re just the most ordinary man there could be.

People are gold medal standard haters :

I hate you more than anything and anyone in the world! I understood and hated you long ago, when I first heard about you, I hated you with all the hatred of my soul.

Women send their boyfriends strange presents :

“Did you receive my hedgehog?” she asked firmly and almost angrily.

TALES OF THE MIDDLE AGES

Comedy flashes all the way through this long strange tale and the funniest part for me was when some people are discussing outbreaks of cannibalism during famines of previous centuries. Somebody says :

One such cannibal, approaching old age, announced of his own accord and without any compulsion that throughout his long and poverty-stricken life he had killed and eaten personally sixty monks and several lay infants…

Later on :

“But could anyone possibly eat sixty monks?” People laughed all round.

THE COMICAL DOSTOYEVSKY NARRATOR

In The Brothers Karamazov and again here the narrator is a bumbling old fart type character who often breaks into the narrative and delivers a speech of his own or says stuff like

Perhaps we shall do no great harm to the vividness of our narrative if we pause here and have recourse to a few explanations

And as the story gets more complicated the narrator frankly gives up trying to understand what’s going on, which I thought was most amusing :

We feel we must confine ourselves to the plain exposition of the facts, as far as possible without particular explanations, for a very simple reason : because we ourselves are hard put to explain what happened.

A RARE WORD

Ten points to the translator David McDuff for using a rare and excellent word

Fanfaronade

Alas, it means “boastful talk” when it should mean something much prettier.

And in general this translation was beautifully readable, as is the book itself.

RATING DOSTO

This is my third big Dostoyevsky book this year and I think The Idiot is overshadowed by Crime & Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov but that’s because they are two of the most extraordinary novels ever. So it’s an unfair comparison. The plot of The Idiot is frenzied and cramful of too many people talking at the same time and trips over itself in the middle (caused I think by Dosto writing to a magazine deadline when he just didn’t know how the story should go) but it’s a hell of a ride so try it some time, say, during a global pandemic.

HOW THE AVERAGE DOSTO CHARACTER BEGINS HIS DAY

In a state of indescribable agitation, bordering on terror -

ليس أصدق و لا أبسط من أمثلة الشعوب و أغنياتهم الشعبية في تصوير أحوال الناس و مشاعرهم الإنسانية على وجه الحقيقة بلا تجميل أو غش.

و قد قيل "الطيب في الزمان ده يقولوا عليه ضعيف" بل يقولون أيضا عبيط و أهبل أي أبله.

"أصل فلان راجل طيب و على نياته" أو كما قالت المطربة إياها "حبيبي على نياته. كل البنات اخواته" و هو أمر لو تعلمون عظيم.

أميرنا هنا ليس طفلا و لا أبله بل رجلا له قلب طفل و ما أدراك ما قلب الطفل. عندما أسأل ابني الصغير ذو الأعوام السبعه: هو انت موجود يا عاصم؟ يرد ببراءة و قد لمعت عيناه: أيوه موجود يا بابا. فأقول مازحا: و ايه اللي يثبت انك موجود؟ يرفع يده أمام عينه و ينظر إليها متأملا ثم ينظر لي و يقول: أهوه موجود أهوه حتى شوف.

لا يخطر ببال الأطفال أننا نداعبهم و نلاعبهم بل و نسخر منهم أحيانا فلماذا؟ هل يجبل الإنسان على الخير أم يجبل على الشر؟ هل نولد صفحات بيضاء تلوثها نقاط الحبر أو تلونها و تزخرفها؟! أم يولد كل منا و لديه بذرة مخبوءة في قرارة نفس مطمئنة أو نفس لوامة أو نفس أمارة بالسوء أو بخليط من كلٍ.

بطلنا الأمير ميشكين هو هنا هذا الطفل قلبا و روحا الرجل جسما و عقلا و علما. كلؤلؤة عاشت في المحار في ظلمات البحر أعواما عديدة فلما خرجت من البحار و ألقيت في التجربة و تلقفتها أيدي الناس أبهرتهم بضوئها و جمالها فصار كل ما عداها قبيحا و كل ما بجوارها زينة لها.

رجل لم تلوثه الخطيئة البشرية الممتدة من المهد إلى اللحد و لم تتملكه الأهواء و ما ملكها و لا عرفها. هذا هو الأبله يا سادة. هو الفارس ال��ي لم يخض حربا من قبل و لا امتطى جوادا.

أما ناستاسيا فيلبوفنا فهي الأيقونة الخالدة للخطيئة التائبة و لكنها توبة من نوع خاص. توبة إبليسية ملائكية في ذات الوقت. تسعى لتلوث نفسها أكثر فأكثر لكي تطهر هذا العالم من الدنس. تحمل طموحاتها السيزيفية التي تصعد بها إلى قمة الجبل كل يوم قاطعة نفس المسافة في نفس الإتجاه بلا أمل في الوصول و لكن يكفيها أن يراها الناس متمرغة في الخطية.

أما أجلايا ايفانوفنا فهو النقيض من ناستاسيا فيلبوفنا أو هي الوجه الأخر للجمال المهان. هي الجمال المصان من كل سوء. هي التي نشأت في الحلية و ولدت في النعيم و مهد لها الطريق لتتنقل من هذا النعيم إلى نعيم مقيم. و كأنه يصور لنا طريقين للجمال كل حسب قدره و بيئته و ظروف مجتمعه.

رواية مجنونة مجنونة مجنونة رغم كل ما بها من مط و تطويل لا مكان له في نسيج الرواية و لا موضوعها إلا أنه مع الرائع ديستوفسكي تطويل جميل نتقبله منه بكل سرور.

تجد إقتباسات الجزء الأول من الرواية

هنا

تجد إقتباسات الجزء الثاني من الرواية

هنا -

«Quería hablar a menudo, pero, la verdad, no sabía qué decir. ¿Sabe usted? En ciertos casos es mejor no decir nada».

Como siempre me pasa con Dostoievski, debo decir que he disfrutado mucho la historia del Príncipe Lev Nikoláievich Mishkin, quien vuelve luego de cuatro años de un sanatario en Suiza para recuperarse... ¿adivinen de qué? si, de epilepsia, como Dostoievski, hacia Pávlovsk en Rusia. De ahí, que, a partir de su epilepsia, es considerado por todos como un idiota.

Al volver a insertarse en la sociedad rusa, la encuentra totalmente fría, distorsionada, mezquina y malévola y es mensaje que Dostoievski realmente quiso mostrar acerca de su presente, allá por 1868-1869.

Debo reconocer que cuando lo leí en su momento “El adolescente” me gustó mucho, pero “El idiota” más aún porque me pareció más fluido, más ameno de leer, tal vez con una historia menos enrevesada y con personajes más marcados (en El adolescente los parentescos confunden, los apellidos se repiten y es necesario apoyarse en las notas aclaratorias al final del libro).

Otro aspecto interesante del libro son los diálogos. Tal vez, lo atribuyo a los traductores que hacen que la lectura del libro que sea fluida.

La concepción de Dostoievski sobre el personaje es muy rica, ya que se propuso crear en Mishkin un personaje totalmente antagónico a Rodion Raskólnikov (recordemos que escribió Crimen y Castigo en 1866) y esto se nota en el carácter del príncipe, dado que el hombre tiene sus convicciones, pero estas no logran ser refutadas o respetadas, como las del Raskólnikov.

Mishkin es débil, ingenuo, influenciable, indeciso. Su relación con las mujeres es conflictiva, enfermiza y angustiante; por momentos por culpa de su propia decisión, en otras por estar negativamente influenciado.

El triángulo amoroso (y enfermizo) que forma que involucra al príncipe con Aglaia Ivanovna y a Nastasia Filíppovna es por donde pasa el nudo de esta historia.

También he de destacar que algunos personajes son muy importantes en esta historia, puesto que tienen implicancia directa. Cito entre ellos a Parfión Rogozhin, a Lizaveta Prokofievna, el General Ivolguin, Ippolit Terentiev, Kostia Lebediev y Gavrila Ardaliónovich, entre otros.

Siempre en las novelas de Dostoievski, las conexiones entre personajes son el modo de llevar adelante la historia.

Como creador de la novela polifónica, Dostoievski le da a sus héroes la función fundamental de que cada uno desarrolle su propia idea y sea portador de su voz, y a la vez, cada una de estas voces hace al conjunto de la historia.

Dicen que Dostoievski quiso hacer confluir en el príncipe Mishkin características de Jesucristo y Don Quijote. Yo particularmente me quedo con el segundo. Realmente hay momentos en que Mishkin va interactuando con los demás personajes de una manera tristemente quijotesca, sobre todo al exponer sus ideales (su discurso sobre el Catolicismo, el Ateísmo y el Nihilismo es muy importante e interesante de leer con detenimiento).

Y por último creo que el concepto de Don Quijote cuadra más porque, sin hacer spoiler, todo eclosiona en el final.

La belleza salvará al mundo proclama el príncipe Mishkin en un pasaje de la novela.

Es probable que la ingenuidad de esta frase encierre la naturaleza de su fracaso. -

Prince Myshkin, 26, arrives in St. Petersburg, Russia by train, "The Beautiful Man" has too much compassion for this cynical age. He believes every person, trusts all, feels the pain of the suffering unfortunates, thus has no common sense. Simple? Gullible? An idiot? Or a Saint? That question only you can decide. Set in the 1860's, the sick prince (he's an epileptic, like the author of this novel) alone, frightened, no relatives or friends or money, in the world, but with a desire to see his beloved native land, again. That he hardly remembers, having lived in Switzerland, treated by a kindly Doctor Schneider, without charge for years. However meets two men that will be friends or enemies (in the future), inside his train compartment. Rogozhin, a young man who can't control his emotions, very unstable, just inheriting a vast fortune, eager to show the whole city, it. And Lebedev , a minor clerk the kind of gentleman who knows everything about Petersburg's important people. Myshkin, doesn't even have proper clothes for the cold, late November day as he steps down into the unknown metropolis. Nevertheless he has valuable information received from the well informed Mr. Lebedev . Seeing General Epanchin retired, his wife has the same name as our "hero," maybe some kind of relation? With difficulties, servants are such doubters and have good reason to be, Myshkin finally gets in the house's family quarters. Meeting the three beautiful daughters of the general, and his volatile and scary wife, Lizaveta. Falling in love with the youngest, prettiest daughter Aglaia, she's 20, very immature, has crushes on every handsome suitor she's introduced to. The inexperienced prince, also loves Nastasya a kept woman he sees soon after, the best looking female in the country. He wants to save this lady, from a life of inevitable degradation and doom, the eternal triangle. Later entering society, they the ruling class look at him, the eccentric Myshkin closely, an oddity a childish fool, not suitable for them as a friend. Yet these citizens have no real ones, themselves ... Good fortune comes to Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin, he inherits a lot of money, unexpectedly, when he goes to Moscow. A letter tells him, naturally he gives away most of it to people, who say the prince owes them money. And the "poor", those asking for a little help, how can he refuse? Fleeing Moscow, the ill man goes back to the Russian capital, the two women in his life, are there. Rents a villa in the suburbs from Mr. Lebedev , invites the consumptive boy that he befriended, Ippolit, ( an unpleasant youth) to stay during his last days and still earns no respect, from anyone ... The "Idiot", has proposed marriage, to both of his loves!

-

Εκεί που πολεμούν οι άνθρωποι με τις αδυναμίες τους και τα όνειρα, εκεί που οι δειλοί πεθαίνουν πριν τον θάνατο τους, εκεί που οι σκέψεις κάνουν πρόβα για να κρύψουν ό,τι αισθάνονται ή να αισθανθούν ό,τι κρύβουν, εκεί που δεν ξέρεις ποιον φόβο σου να αγαπήσεις περισσότερο,

εκεί θα περιμένει πάντα ένας «ηλίθιος» να σε καλωσορίσει στο μυαλό του.

Βιβλίο υπέροχο. Βιβλίο δύσκολο. Βιβλίο εμμονικό. Βιβλίο κλειστοφοβικό. Βιβλίο επαναλαμβανόμενο, σκοτεινό και ασυμβίβαστο.

Σκληρή διαβάθμιση αξιών. Κλασική μελέτη κοινωνικών φαινομένων. Ένας καθρέφτης που δεν κολακεύει.

Αν τον κοιτάξεις προσεκτικά θα δεις τον εαυτό σου και ένα ράγισμα στη μέση. Ανεπαίσθητο και βαθύ ράγισμα, διπλασιάζει είδωλα και σε αναγκάζει να συγκρίνεις τις κατάρες με τις ευχές.

Ο «ηλίθιος», ο πρίγκιπας Μίσκιν, είναι ο υπέρλαμπρος κεντρικός, διττός χαρακτήρας.

Αυτός κρατάει το ραγισμένο καθρέφτη.

Μια υπέροχη ψυχή που βρίσκεται σε σύγχυση.

Μια λατρεμένη ύπαρξη χαρισματικά άρρωστη που ψάχνει το νόημα της ζωής και οδηγείται απο την επιθυμία του για ζωή.

Οι προθέσεις του πάντα καλές μα ελαττωματικές στην εκτέλεση τους.

Μια ύπαρξη που έχει σχεδόν ανακάμψει απο τις επιληπτικές κρίσεις και αποκαλύπτει τα κίνητρα του ως εχέγγυα προς την ανθρώπινη φύση.

Προσπαθεί να προσεγγίσει τους συνανθρώπους του με διάθεση παιδικής αφέλειας, αγνότητας, τρυφερότητας και συμπόνιας.

Ως ηλίθιος αντιλαμβάνεται διαφορετικά τον κόσμο.

Ως άρρωστος επιδεικνύει τις σκέψεις του που είναι αντανακλάσεις της ειλικρίνειας του, του πλούτου της αγγελικής καρδιάς του και της ευρύτητας του μυαλού του.

Όσο απίστευτο κι αν φαίνεται αυτός ο ηλίθιος έχει μια ανώτερη κατανόηση και έκφραση. Μια υπέρτατη διαχείριση των συναισθηματικών δυνάμεων που τον προωθούν να υπαγορεύει σχεδόν,τις καταστρεπτικές ενέργειες των ανθρώπων γύρω του.

Ο ηλίθιος αυτός, ο πρίγκιπας Μίσκιν, είναι μια αστείρευτη πηγή έμπνευσης για κάθε άνθρωπο.

Όποιος τον κρίνει ως αθώα παθητικό πρόσωπο έχει χάσει την ουσία.

Ο χαρακτήρας του διακρίνεται κυρίως για την οξυμένη αντίληψη προς τη σκέψη και τη δράση, τη βαθιά κατανόηση όλων των καταστάσεων και την ευφυΐα της συναισθηματικής του νοημοσύνης.

Είναι ηλίθιος, είναι πράγματι, διαφέρει απο όλους.

Η ηλιθιότητα του μεταφέρεται συνοπτικά με αλληλεπιδράσεις που δημιουργούν τόσο αγάπη, όσο και δυσαρέσκεια.

Παλεύει να βρει χώρο για να ζήσει μέσα σε έναν κόσμο υλιστικό, αυτός όμως δεν ενδιαφέρεται για τα υλικά αγαθά, διακρίνει αλλού τον πλούτο κι έτσι δεν μπορούν να τον κλέψουν στη μοιρασιά.

Μα πόσο ηλίθιος πια, πόσο;

Ραγίζει η καρδιά του και σπάει απο ενα παιδικό χαμόγελο, λιώνει η ψυχή του, καίγεται, απο το χάδι μιας ερωτικής διάπυρης ματιάς, μα είναι παγερά αδιάφορος μπροστά στην κοινωνική καταξίωση, την αριστοκρατική εκλεπτυσμένη απληστία, τις φιλοξοξίες για εξουσία και περιουσία, την πολυτέλεια, το κέρδος.

Πόσο πιο ηλίθιος, όταν δεν μπορεί να σταθεί στην κλασική τάξη της αστικής υποκρισίας.

Όταν αρνείται να συμμετέχει στην διαφθορά και την πλάνη ως υποστηρικτικό σκουπίδι νευρωτικών κληρονόμων.

Όταν ανάμεσα σε σνομπ εκμεταλλευτές και ανήθικους νάρκισσους προτιμάει το βάθος της αγάπης και της αυτοθυσίας.

Ο ηλίθιος λοιπόν αυτός, δεν δέχεται κοσμικά σύνορα που χαράζουν το σώμα του πλανήτη.

Δεν μπορεί να διαλέξει ανάμεσα σε αγάπη και μίσος. Το μίσος δεν υπάρχει, δεν το γνώρισε, δεν το ένιωσε ποτέ.

Προσπαθεί να χειριστεί την αγάπη του.

Να κατανοήσουν όλοι πως δεν γίνεται να μην αγαπάει, δεν μπορεί να υπάρχει χωρίς αγάπη.

Αγαπάει καθολικά και απεριόριστα χωρίς να μπορεί να συμφιλιώσει το παθιασμένο και το συμπονετικό.

Ακόμη κι όταν βρίσκεται στη δίνη του ερωτικού οίστρου ανάμεσα σε δυο γυναίκες, του φαίνεται αδιανόητη η επιλογή, αρρωσταίνει, χάνεται μπροστά στο δίλημμα που του θέτουν οι κανόνες. Αγάπη απο οίκτο και δέος ή έρωτας παθους με αγάπη γαλήνια και παντοτινή;

Ένα επιληπτικό αριστούργημα γραμμένο απο μια λογοτεχνική ιδιοφυΐα.

Κεντρικός άξονας ο ηλίθιος πρίγκιπας Μίσκιν και γύρω του πλήθος χαρακτήρων φυλακισ��ένων σε ένα τρομερό παιχνίδι πραγματικότητας.

Είναι όλοι τους αξιοθαύμαστοι, φιλοσοφικοί,πολύχρωμοι, παρορμητικοί, ενδοσκοπικοί, ενεργητικοί, επιλεγμένοι σοφά για να συμμετέχουν σε αυτό το παιχνίδι, σε αυτή την παράσταση ιδεών.

Ο Ντοστογέφσκι αποκαλύπτει, διερευνά και επηρεάζει.

Μέσα στο παιχνίδι του πετάει νοοτροπίες, πάθη, λάθη, σκέψεις, ενέργειες,που εξηγούν τη φύση του ανθρώπου και της κοινωνίας.

Προάγουν την ανθρώπινη βούληση με ποικίλους βαθμούς διαταραχής της προσωπικότητας, παρανοϊκές παραληρηματικές ιδέες ή μανιακές επιδι��ξεις.

Επομένως η ουσία της αφήγησης βυθίζεται σε μια θάλασσα λάσπης απο εκούσια κοινωνικά και κακοπροαίρετα σχόλια, ιδιοσυγκρασίες ξεχωριστές και σουρεαλιστική βραδύτητα συσχετισμών.

Φυσικά σε αυτό το παιχνίδι δεν υπάρχουν νικητές και σε αυτό το μυθιστόρημα δεν υπάρχει τίποτα λιγότερο απο την τελειότητα.

Δύσκολο, βαρύ και σπουδαίο πνευματικό έργο.

✡️🟦✡️🟦

Σας προκαλώ

Αντέχετε;

Καλή ανάγνωση.

Πολλούς ασπασμούς. -

The Idiot is a remarkable literary feat; a true accomplishment. It not only shows and represents true human complexity, but it births it, both in the inner workings of its passionate characters, and in the overall story. It's replete with patient, mind testing issues that spring the reader’s level of understanding back-and-fourth; yet its emotional intensity is felt throughout. It speaks truth of our striving human conditions; our emotions which only know the truth of their existence in the moment; yet it is a true and pure novel, like the heart of our unusual but endearing hero, Prince Myshkin: our idiot.

Nobody brings the drama like Fyodor: nobody. Yet despite all the exclamation points and the excessively passionate characters -- who all seem to speak with great clarity, with penetrating philosophical insight -- Dostoevsky novels still feel very real to me. Despite its great entertainment value and all the outbursts from its characters, very real emotional boundaries are pushed in very natural, all encompassing ways. What The Idiot bespeaks is something about life that is so real and true that the novel, while very intense, feels completely unexaggerated.

Dostoevsky novels don’t take place in, but are a world of both utter emotional madness and pure genius. And they display how the two are often inseparable:

"He fell to thinking, among other things, about his epileptic condition, that there was a stage in it just before the fit itself (if the fit occurred while he was awake), when suddenly, amidst the sadness, the darkness of soul, the pressure, his brain would momentarily catch fire, as it were, and all his life's forces would be strained at once in an extraordinary impulse. The sense of life, of self-awareness, increased nearly tenfold in these moments, which flashed by like lightning. His mind, his heart were lit up with an extraordinary light; all his agitation, all his doubts, all his worries were as if placated at once, resolved in a sort of sublime tranquility, filled with serene, harmonious joy, and hope, filled with reason and ultimate cause."

These characters, none of them were "all bad" or "all good"; in fact there was not one single character in this entire novel that I didn't feel both sympathy and contempt for, at various stages.

The Idiot is epic. The way it played out will have my mind reeling for weeks, I know. And I like that. I like that a lot.

"But I'll add though that there is something at the bottom of every new human thought, every thought of genius, or even every earnest thought that springs up in any brain, which can never be communicated to others, even if one were to write volumes about it and were explaining one's idea for thirty-five years; there's something left which cannot be induced to emerge from your brain, and remains with you forever; and with it you will die, without communicating to anyone perhaps, the most important of your ideas." -

چقدر عالی بود. یکی از بهترین رمانهایی که امسال خواندم. داستایوسکی نابغه همیشه باعث بهت و حیرت من میشود. از تعداد صفحات زیاد آن نترسید و اگر به نویسندگان روس علاقهمند هستید حتماً آن را بخوانید. ترجمه حبیبی محشر بود. چند فیلم اقتباس شده از این رمان و چند فیلم هم با الهام از آن ساخته شده است. من به خاطر علاقه وافر به کوروساوا اقتباس او را دیدم، اگر علاقهمند بودید پس از مطالعهی کتاب آن را ببینید.

The idiot (1951) 7.3 Kurosawa

The idiot (1958) 7.6 Ivan Pyryev

و در پایان

زنده باد داستایوسکی

زنده باد کوروساوا

و زنده باد سروش حبیبی

********************************************************************************

این اهانت است به روح انسان، و غیر از این هیچ نیست! دین به ما میگوید: "نکش!" ولی انسانی را میکشند چون آدم کشته! این که نمیشود! من این صحنه را یک ماه پیش دیدم و تا امروز هنوز آن را جلو چشم دارم. ص38 کتاب

حقیقت این است که از معاشرت با آدمبزرگها خوشم نمیآید. این چیزی است که خودم مدتهاست فهمیدهام. علتش هم این است که نمیتوانم با آنها سر کنم. ص 121 کتاب

من پول میخواهم. میدانید اگر پول داشته باشم دیگر کسی مرا یک آدم عادی نمیشمارد. آن وقت من از هر جهت برجسته و غیر از دیگران میشوم. پول از این جهت از همه چیز حقیرتر و نفرتانگیزتر است که حتی آدم را صاحب ذوق میکند و تا دنیا دنیاست همین خواهد بود. ص 203 کتاب

عادت به راحت و تجمل، به آسانی انسان را مبتلا میکند و در بند میکشد و چون تجمل کمکم به صورت ضرورت درآمد خلاصی از بند آن بسیار دشوار است. ص222 کتاب

خوشحالی یک مادر وقتی اولین لبخند طفلش را میبیند مثل خوشحالی خداست وقتی که از آن بالای آسمانش گناهکاری را میبیند که پشیمان شده و از سر صدق بخشایش میخواهد. ص 357 کتاب

همدردی بزرگترین و شاید یگانه قانون وجود برای تمامی بشریت است. ص 372 کتاب

"ولی طبیعت به ریش ما میخندد." ناگهان با هیجان و حرارت بسیار گفت: "برای چه بهترین موجودات را خلق میکند تا بعد به ریششان بخندد؟ مگر نکرده؟ تنها مخلوقی را که همه به کمالش اعتراف میکردند آفرید و بعد از آنکه او را به همه شناساند حرفهایی را بر زبانش گذاشت که خون جاری کرد. آنقدر خون جاری شد که اگر همزمان ریخته شده بود مردم به یقین در آن غرق شده بودند. ص 476 کتاب

ناگهان اشتیاق عجیبی احساس کرد که همه چیز را همین جا رها کند و خود به همان جایی برود که از آن آمده بود، و برود به جایی، هرچه دورتر بهتر، جایی دورافتاده و فوراً برود، بی خداحافظی با کسی. احساس میکرد که اگر، ولو چند روز دیگر، آنجا بماند به داخل این دنیا کشیده میشود و بیبازگشت. ص 493 کتاب

در کشور ما اگر دستت به جایی بند نباشد و پشتیبانهای متنفذ نداشته باشی تبار کهن به کاری نمیآید. ص 528 کتاب

کهنهکارترین جانی که دیگر اصلاح شدنی نیست، هر چه باشد میداند که "جانی" است، و گرچه از کاری که کرده پشیمان نیست، پیش وجدان خود میداند که کار زشتی کرده است، و همهی آنها همین طورند. ص 544 کتاب

همه شراب در سر دارند، آن هم شامپانی و ظاهراً تازه هم شروع نکردهاند، زیرا بسیاری از این شبزندهداران از آن آب سرد آتشین به شوری شیرین آمده بودند. ص 589 کتاب

غریزهی تباه سازی خود و غریزهی بقا در وجود آدمها به یک اندازه نیرومند است. تسلط شیطان و سلطنت ایمان، تا ابد، یا بگوییم تا زمانی که ما نمیدانیم کی خواهد رسید، با هم برابرند. ص 601 کتاب

اطمینان داشته باشید که خوشبختی کریستف کلمب زمانی نبود که آمریکا را کشف کرد بلکه زمانی خوشبخت بود که میکوشید آن را کشف کند... اینجا صحبت زندگی است. فقط زندگی. صحبت تلاش در کشف زندگی است و نه در کشف آن. ص 602 کتاب

صحبت یک زندگی است و راهی بینهایت شاخه شاخه که اسرار آن هرچه هست بر ما پوشیده است. بهترین شطرنج بازان، تواناترین و تیزهوشترینشان بیش از چند حرکت را نمیتوانند از پیش حساب کنند. کار یک شطرنج باز فرانسوی را که میتوانست تا ده حرکت خود را پیشبینی کند اعجاز شمردهاند. حال آنکه چه بیشمارند حرکتهای ممکن، که ما از آنها بیاطلاعیم. شما با پاشیدن بذر خود و بذل نیکی به هر شکلی که باشد جزئی از خود را به دیگری می��خشید و جزئی از دیگری را در خود میپذیرید. ص 627 کتاب

ظرافت احساس و عزت نفس از دل آدم سرچشمه میگیرد و چیزی نیست که معلم رقص به کسی تعلیم بدهد. ص 700 کتاب

آدم نمیتواند مظهر کمال را دوست داشته باشد. آدم در برابر صورت کمال فقط میتواند محو تماشا باشد. ص 724 کتاب

در حقیقت هیچ چیز ناراحت کنندهتر از این نیست که آدم مثلاً ثروتمند و خوشنام و باشعور و خوش صورت و حتی پسندیده سیرت باشد و تحصیلاتش هم بد نباشد و در عین حال هیچ قریحهای، اصالتی، کیفیتی غیرعادی ولو در خور نیشخند، هیچ فکر اصیلی که از ذهن خودش جوشیده باشد نداشته باشد و از هر جهت مثل دیگران باشد! ثروتمند هستی اما روتشیلد نیستی. خانوادهات خوشنام است اما هرگز با هیچ کار درخشانی نمایان نشده است. صورتت قشنگ است اما جذاب نیست. تحصیلات خوبی کردهای اما نمیتوانی از آن بهرهای برداری. باهوش و فهمیدهای اما فکر بکری هرگز در ذهنت پیدا نمیشود. بد کسی را نمیخواهی اما خیری هم به کسی نمیرسانی، از هر نظر که فکر کنی نه بویی و نه خاصیتی! ص 736 کتاب

بعضی وقتها وضع طوری است که انسان مجاز است که پلهای پشت سر خود را خراب کند و دیگر به خانه باز نیاید. ص 891 کتاب

-

اما همان بِه که میگفتند: «مرد دانا در میان آدمیان چنان میگردد که در میان جانوران.»|نیچه

ابله کیست؟

مردم به آن کسی که بدهبِستانهایش بیحساب و کتاب باشد و به دنیا و امورش نگاهی کاسبکارانه نداشته باشد می گویند ابله. اما دو نوع ابله داریم. یکی آن ابلهی که از سرِ پایین بودن ضریب هوشی چنان میکند و یکی آن ابله نابغهای که چیزی بهتر از داد و ستدهای معاملاتی/معاشرتی کشف کرده باشد. یک چنین ابلهی بدون چشمداشت به دیگران خوبی می کند. از کسی بدی به دل نمی گیرد و کسی را از خود نمی رنجاند. در عوض از چیزهایی می تواند لذت ببرد که دیگران قادر به لذت بردن از آن نیستند. از قطعه ای شعر، از بویی خوش، از تماشای منظره ای چشم نواز و یا شنیدن آوای پرندهای در طبیعت. و تمام اینها را در این جمله می توان خلاصه کرد که این ابله، از رسیدن به مقصد لذت نمی برد، بلکه از طی کردن و پیمودنِ مسیر لذت می برد. خواه به مقصد برسد و خواه نرسد. برای او فرقی ندارد. ابله در پی کشف زندگی است و این کشف کردن زندگی نیست که او را محظوظ می کند، بلکه "در پی" کشف زندگی بودن است که او را محظوظ می کند.

با این همه، طبیعی است که دیگران او را ابله بشمارند، زیرا او نه در پی کسب مقام است و نه حرص ثروت اندوزی در سر دارد. او دیدگاهی کاسبکارانه ندارد و خیلی وقت ها متضرر می شود. متضرر، البته از نگاهِ عاقلان.

می گویند داستایفسکی شخصیت پرنس میشکین، قهرمان رمان ابله را از روی مسیح گرته برداشته است. و این بیراه نیست. زیرا وقتی اوصاف ظاهری پرنس میشکین را می خوانید انگار جلوی یکی از تابلوهای نقاشی مسیح ارتودوکسی ایستاده اید. در ادبیاتِ پیش از داستایفسکی و معاصر او، چند شخصیت ابلهِ برجسته داشتهایم: دنکیشوت، پیکویک و ژانوالژان. اما هر کدام از آنها معایبی را داشتند که داستایفسکی می خواست قهرمانی که خلق می کند، در عینِ بلاهتِ ظاهری، از آن معایب بری باشد. انسانی که در ��اهر معمولی به نظر برسد اما قلبِ ساده ای داشته باشد. حتا داستایفسکی به این قهرمان لقب پرنس می دهد. برای اینکه خواننده از پیش برای او احترامی قائل باشد و تربیت صحیح موروثیای را برای او قائل بشود.

به گونههای استخوانیِ داستایفسکی بنگیرید.

او از آسایش خود گذشت تا روحِ ما را به تعالی برساند.

داستایفسکی رمان ابله را بعد از رمان جنایت و مکافات نوشت. و برای سیرِ مطالعه آثار داستایفسکی بهتر است از توالی نگارششان پیروی کنیم. رمانی که خواندنش هفته ها به طول می انجامد نوشتنش ماه ما به طول انجامیده است. کتابی که خلق کردنش برای نویسنده دشوار می نموده است، ��بیعی است که مطالعه اش برای خواننده نیز دشوار بنماید. اما بدون شک این یک رمانِ معمولی نیست و ارزش خوانده شدن دارد. قیمتی که با گذاشتن زمانمان برای خواندنش پرداخت می کنیم در مقابل بهره ای که از آن می بریم ناچیز است.

دربارهی آن ابله که من خواندم

ابله رمان حجیمی است.دو ترجمه دارد. یکی سروش حبیبی و یکی مهری آهی. من ترجمه ی سروش حبیبی را خواندهام اما برای بار دیگر تصمیم دارم ترجمهی مهری آهی را بخوانم. چون روسی بلد نیستم و تصمیم هم ندارم روسی یاد بگیرم، با خواندن دو ترجمه می خوام مطمئن شوم چیزی را از دست نداده باشم. حتا در خاطرات چند شاعر و نویسنده خوانده ام که در پیرانهی عمر آثار داستایفسکی را بازخوانی کرده اند و چیزهای عجیبی از آن دریافته اند. دوباره خوانی همیشه چیزهای جدیدی برای آدم دارد.

گزیده ای از کتاب ابله که خیلی وقتها بازخوانی می کنم را اینجا میآورم. این در حقیقت عقیدهی خودِ داستایفسکی است که از زبان شخصیتی داستانی گفته می شود و می توانم بگویم نگاهی نبوغ آمیز نسبت به دنیا و آنچه که در آن هست می باشد:

نمی فهمیدم چطور ا��ن آدم هایی که سال های دراز زندگی در پیش دارند نمی توانند ثروتمند بشوند(گرچه هنوز هم این معما برایم ناگشوده مانده). مرد فقیری رامی شناختم که بعدها شنیدم از گرسنگی مرده است و یادم هست که از این خبر کفرم در آمد. اگر ممکن می بود که این مرد زنده بشود گمان می کنم او را می کشتم. گاهی یک هفته ای حالم بهتر می شد و از خانه بیرون می رفتم. اما عاقبت از دیدن خیابان و مردم چنان به خشم می آمدم که تاچند روز به عمد در به روی خود می بستم، گرچه می توانستم مثل همه بیرون بروم. تحمل دیدن این همه آدم را که مدام در تکاپویند و به هر کنج و کنار سر می کشند و پیوسته دل مشغول و عبوس و نگران اند و در پیاده رو از کنار من می گذرند، نداشتم. حاصل این غم دائم و نگرانی و تکاپوی همیشگی و این کینهی تمام نشدنی آنها چیست؟ (زیرا آن ها بدخواهاند، بد خواه و بد نهاد!) گناه دیگران چیست که آن ها بدبخت اند و با وجود شصت سالی که در پیش دارند، نمی توانند از زندگی لذت ببرند؟... همه، دستهای پینه بستهی خود را نشان می دهند و باخشم فریاد می زنند: "ما مثل خر کار می کنیم و جان می کَنیم و مثل سگ گرسنگی می کشیم و دیگران به جای کار کیف می کنند و ثروتمند هم هستند."(و این ورد همیشگی زبانشانست!) من که دلم برای این جور احمق های وامانده اصلاً نمی سوزد. نه حالا می سوزد و نه هرگز سوخته. و این حرف را با سربلندی می زنم...اگر او میلیون میلیون پول ندارد تقصیر کیست؟ گناه از کیست که او کوه کوه سکههای طلای ناپلئون و لویی ندارد، بله، کوه کوه، مثل سرسره های کارناوال. اگر حکم مرگش قطعی نیست هر کار که بخواهد می تواند بکند. کسی چه کند که او این را نمی فهمد؟ -

I have been trying to fill this review box ever since I finished this book. After writing and rewriting about this book, I think I have finally come close to what I feel about this book. I don’t think I can ever do justice to the beauty of this book but I still wanted to write few things about it. I started reading this novel last year. Put on pause twice, then finally finishing it this month. I was so relieved not only because I managed to read it, but also because it is one of those books that are still a treat to read even after 150 years of its publication.

Story revolves around Prince Myshkin who arrived in Russia from Switzerland. There he meet Rogozhin on the train and befriends him. Then he went to see his distant relatives General and meet family. Here he sees a picture of Nastasya Fillipovna and falls in love with her. Things get complicated when he proposes her and she rejects him for Rogozhin, who is also madly in love with her. On the day of marriage she elopes to be with Rogozhin. Myshkin finds love in Agalaya but all hell loose breaks when once again Nastasya decides that she is still in love with the Prince.

In Prince Myshkin, Mr. Dostoyovesky created a beautiful soul. A man who is free of deception, lies, concoction, and brutally honest. A man who always put others before his own happiness. A man whom no one can hate even if one tries they fail miserably and end up falling in love with this simpleton. So many times I felt so angry when people called him mad, fool, idiot, because they failed to see the beautiful heart that the Prince had. Then one can’t blame them for we always hate people who are too good and have the qualities that we don’t possess. We want to be clever but hate it when outsmarted by cleverer person. But our prince is beyond all this, he just love and think highly of others even if those very people are trying to drag him down. And that’s the reason they find it so hard to begrudge him.

While the prince has no vile motives, the two leading ladies of the novel have intentions that were hard to grasp upon for me. One minute they were madly in love with Prince, but in the next moment they would leave him and tell him that they don’t love him. They could not bear the thought of him being with another, oh how they made sure of it. One kept running away from him, and the other kept him on the edge with her own confusion. They drove him mad and how I wanted him to leave both of them to their fate and go some other place where he would get peace of mind but they would not let him walk away.

Dostoyovesky has written a stunning story that evoked so many emotions in me. I found myself teary, laughing, distressed, full of hatred, scared, angry, and sad on behalf of the prince. I don’t think one will get to meet a person like Prince in real life but it is easy to see the goons that surround him in everyday life. His characters are deeply flawed, impulsive, and dense but at the same time they make me understand (or at least I tried to) how human nature works.

I absolutely loved this book, and I am definitely reading his other works but I think I will still take another year to get out of this world. -

Do you answer ‘yes’ to any of the following questions?

1. You ever sleep in another person’s house for the first time, not wanting to turn on a light to see your way to the toilet, and run into a wall?

2. You ever been in a public building at night and the power fails, and you run into a wall?

3. You ever been camping with an overcast night and straggle into the woods to take a pee, and run into a wall of shrubbery?

4. You ever been in a leadership reaction course, blindfolded, and run into a wall?

5. You ever been deployed to Qatar in the transition billeting tent at night, not wanting to disturb all the soldiers with your mag-light, and run into a tent wall?

What do these questions have in common? 3 things. One, you’ve lost your primary sense--eyesight. Two, you’ve run into something through which you can’t pass. Three, to continue you must turn east or west. This is exactly how I felt when I read The Idiot. Lost, in a strange place, against a barrier. (preview: it’s all about the translator, paragraph 10)

Then I agonized for a week about posting a review of a piece of monolithic literature to which I award only 2 stars. How the hell, dude, can you award 2 stars to an uber-classic? Did you forget it was Dostoevsky? Do you realize that among your 56 friends on Goodreads that 2 stars is the lowest anyone has rated it? You missed something; you’re ignorant!

And I truly subjected myself to several good harangues. I reread the lengthy, academic foreword and afterword. I thought deeply about the book. I stretched my mind, my cognitive abilities, each time against a wall. I was really concerned about your opinion of me, as a reader, as a consumer of serious literature, as a trustworthy, balanced critic of dense writing.

Then it appeared to me, like a turn in the dark. Screw you!! I’m not writing this for you. I write reviews to capture how I feel about a specific novel at a particular place and time in my life. It’s completely fair to award 2 stars to Dostoevsky. At this particular time in my life--as I realize the Deepwater Horizon oil spill may have been overblown by the media, as I decide whether or not to delete my Facebook account, as I realize Obama’s economic plan is an absolute failure with unemployment remaining above 9% for the next 12 months and home values not rebounding for 36 months, as I wonder if next will be as tough as the previous year raising my 3 young kids--at this particular time in my life, I didn’t very much enjoy The Idiot. This is where I’m at in time and place with The Idiot, and I’m so glad to capture feelings other than a middling 3 stars (which is sometimes a rounding error). 2 stars is harsh, but fair.

I read Crime and Punishment twice, and think The Brothers Karamazov one of the best 5 books I ever read. I’ve been under the spell of Dostoevsky for nearly half my life. So my lean this week into The Idiot was a disappointment.

Here’s what the author said about the book: “There’s much in the novel...that didn’t come off, but something did come off. I don’t stand behind my novel, but I do stand behind my idea.” Authors sometimes give themselves a giant pat on the back, but couch it in self-deprecating language. As if to say the ideas in the novel were so august, so pantheon, so divine that their ability to define or make sense of these ideas with terrestrial words resulted, simply, in a spatchcock of human themes. Ignore the writing. The message is in the idea. Come on, Fyodor, we all know you write like an immortal.

The Idiot is brimming with philosophical inquiry into people’s lives, society, culture, and history. Immutable, transcendent ideas about which Russian writers always grapple. The authors of the foreword/afterword reveal and underscore dozens of themes in the book. They discuss mechanics and perspectives and symbols. They discuss Russian history and the Russian concept of suffering, and how these were adroitly parsed among the characters. And how the characters themselves represented the unique attributes--in splinter form--of the Russian whole.

Well that’s all great. You read it and take from it what you want. I found it tangled, hard to follow, uninteresting. The characters were so weighed down by being representatives of the Russian whole that they failed to be engaging characters by themselves. And so unlike Dostoevsky, I found not a single sentence worth transcribing here. In 660 pages, wow, nothing worth remembering. How unfulfilling. Certainly nothing like

THIS powerful, euphonic sentence.

(Important) Because I know Fyodor can bring the noise, it leads me to believe that the translation is faulty, dated. Indeed, I read the version translated originally in 1913 by Olga Carlisle. It’s the staid, orthodox version. Perhaps if I read the translation by Larissa Volokonsky, then I would’ve been in measure with the writing. She won the 2002 Efim Etkind Translation Award for her work on The Idiot, for Chris’akes!! Swoon. Cuss. Paradise Lost! Alas, I won’t reread The Idiot. It’s just too long...and me, I’m too slow a reader. I’ll read The Possessed in a couple years. The experts call it a more traditional story on par with CAP and TBK. Dostoevsky is too fine a writer to abandon, and so I won’t.

Another problem I had with the Carlisle translation was the melodramatic interpretation of character staging. Let me, for example, open the book to page 580--a random choice--and list every instance on both pages where the character staging is electrified.

...got up rather late and immediately recalled...

...first moment she burst into tears...

...the prince at once reassured her...

...he was suddenly struck by the strong compassion...

...Vera blushed deeply...

...she cried in alarm, quickly drawing her hand away...

...went away in a strangely troubled state...

...her father had hurried off...

...Koyla ran in, also for only a minute...

...in a great hurry...

...was in a state of intense and troubled agitation...

...was deeply and violently moved...

...poor boy was thunderstruck...

...quietly burst into tears...

...he jumped up...

...hurriedly inquired about...

...added in haste...

...was predicting disaster...

...was asking pointed questions...

...with a gesture of vexation...

...accursed morbid mistrustfulness...

...in the form of an order, abruptly, dryly, without explanation...

...suddenly turning around...

...and feverishly looked at his watch...

Remember, this came from a total of 1200 printed words. The entire book is similarly charged. I got tired of reading all this ‘juiced’ action. Did Dostoevsky intend 660 pages of melododrama, or was this a translator’s interpretation? I got robbed, man. Bad translation. The review stops here. -

Is being different from others a flaw?

The difference we do not understand and will reduce, isolate, or denigrate is how to forge a society of reasonable intelligence.

With the strength of his style, the author leads us into this philosophy to make us ask questions and leave us with questions about our views of yesterday. -

This book disappointed me. I never thought I would be saying this with regard to a book by Dostoyevsky, but it's true. Perhaps this is only because I’ve been spoiled by reading The Brothers Karamazov, which even admirers of The Idiot will likely admit is a much stronger work. Yet I was not merely unimpressed by this work, but was often greatly frustrated by it. To be concise, I found The Idiot to be a rambling mess.

Anyone familiar with Dostoyevsky’s work will know that he is not a versatile artist. He is a writer with obvious flaws and with tremendous strengths. It is, therefore, incumbent on the reader to look past his demerits—his clunky dialogue, his exaggerated personalities, his slipshod plots—in order to appreciate his peculiar genius, if the reader is to get anything at all out of his works. In this book, however, I found his usual deficiencies to be overabundant, and his usual brilliance to be pushed to the side.

Let us take the protagonist. He is supposed to be a nearly perfect man, the very picture of benevolence and kindness. Yet I was not at all impressed with Prince Myshkin. He was a polite and amiable fellow, sure. But did he go very far out of his way to help others? Was he capable of doing any good? Was he busying himself in improving the world? Not at all. Rather, Myshkin comes off as rather bumbling and self-absorbed.

This was, of course, partly Dostoyevsky’s goal—to show how true kindness can make you vulnerable and lead to inactivity and ruin. But the impression I was left with was not of a kind man tragically taken advantage of, but a man who was simply incapable of dealing with the world; a man not overly virtuous, but simply inept. This is in stark contrast to two of Dostoyevsky’s other characters, Father Zossima and Alyosha Karamazov, both of whom I found to be more wise, more open-hearted, more interesting, and many times more capable than Prince Myshkin—who, to be frank, is so passive as to be dull.

It is clear that much of this novel’s design is due to the influence of Don Quixote, which Dostoyevsky refers to many times during the course of this work. Prince Myshkin is something of a Quixotic character—a bit of a dunderhead, a bit of a loon—except that he is tragic, whereas the Don is comic. We also see Cervantes’s influence in the large and unwieldy cast of minor characters (something not typical of Dostoyevsky), who continually intrude, sometimes violently, on the main action of the plot. It seems that Dostoyevsky vaguely wanted to write a genuine burlesque, with a witless protagonist suffering misadventure after misadventure in the real world. But of course, Dostoyevsky turns this general idea into a distorted nightmare that very often borders on absurdity.

Either from lack of practice, or simply because he wrote this novel very quickly while in dire financial straits, Dostoyevsky didn’t seem up to the challenge of keeping track of all these minor characters. All of them act erratically, often to the point that they are unrecognizable one scene to the next. They suffer acute changes of mood and opinion, veering from emotion to emotion too quickly for the reader to even keep up. Admittedly, this is characteristic of much of Dostoyevsky’s writing; and to be sure, he often uses fitful, unpredictable, and irrational characters to brilliant effect, keeping the reader constantly on edge. But in this work, I found it to be so overdone as produce a kind of apathy in me. I couldn’t wrap my head around the characters enough to care about them; and since I didn’t really know them, and thus didn’t expect anything from them, they couldn’t surprise me—since surprise is the thwarting of expectation.

Perhaps what I most regretted about this design, however, was not the shoddy characterization, but how it forced Dostoyevsky to deal with his typical themes. Instead of putting his always arresting philosophical speeches into the mouths of major characters, several minor characters butt into the story in order to deliver lengthy and, from the perspective of the story, rather pointless harangues that are promptly swept to the side. So instead of the critique of modern society, nihilism, rationalism, and his analysis of the decline of religion being in the forefront, these themes are peripheral, which I think is a shame.

This is not to mention the several incidents that Dostoyevsky introduces apparently only to stretch the page-count (he was being paid by the page). The most egregious example of this was when a young man bursts into a drawing room, spends an hour claiming that he is the son of Prince Myshkin’s doctor and is thus owed money, and reads a lengthy and absurd article that Myshkin then refutes point by point; then, another minor character announces that he has been researching this man for some time (why?), and reveals that his claim to be the son of the doctor is false—and this, after an interminable conversation with many other side-remarks—so that the whole affair comes to absolutely nothing, and isn’t at all important to the rest of the book.

This enormous amount of space dedicated to side issues is especially perplexing when one considers that major plot developments are, by contrast, introduced willy-nilly without much ado—such as when Prince Myshkin simply announces, in the midst of a major scene, that he has inherited a large sum of money.

To cut short this review, I found this to be a deeply flawed book, one that obviously needed several more drafts before it could be really compelling. I am still giving it three stars, however, because there are occasional brilliant flashes. I especially liked when Prince Myshkin spoke of executions, and Lebedev’s story about the repentant cannibal who killed and ate monks. Yet these shining moments were overshadowed by the many pages of tedium. Of course, it’s quite possible that I missed something. One of my friends is a big fan of Dostoyevsky, and he says this book is his favorite. But until my eyes are opened to this book's secret merit, I will steer those who ask to Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov, which are not merely occasionally brilliant, but splendid from beginning to end. -