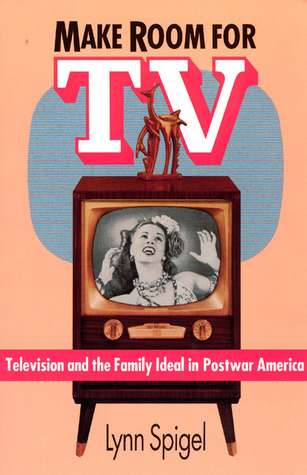

| Title | : | Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0226769674 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780226769677 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 246 |

| Publication | : | First published June 1, 1992 |

In this fascinating book, Lynn Spigel chronicles the enormous impact of television in the formative years of the new how, over the course of a single decade, television became an intimate part of everyday life. What did Americans expect from it? What effects did the new daily ritual of watching television have on children? Was television welcomed as an unprecedented "window on the world," or as a "one-eyed monster" that would disrupt households and corrupt children?

Drawing on an ambitious array of unconventional sources, from sitcom scripts to articles and advertisements in women's magazines, Spigel offers the fullest available account of the popular response to television in the postwar years. She chronicles the role of television as a focus for evolving debates on issues ranging from the ideal of the perfect family and changes in women's role within the household to new uses of domestic space. The arrival of television did more than turn the living room into a private it offered a national stage on which to play out and resolve conflicts about the way Americans should live.

Spigel chronicles this lively and contentious debate as it took place in the popular media. Of particular interest is her treatment of the way in which the phenomenon of television itself was constantly deliberated—from how programs should be watched to where the set was placed to whether Mom, Dad, or kids should control the dial.

Make Room for TV combines a powerful analysis of the growth of electronic culture with a nuanced social history of family life in postwar America, offering a provocative glimpse of the way television became the mirror of so many of America's hopes and fears and dreams.

Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America Reviews

-

3.5 stars -- While occasionally dry, this study of TV's impact upon the late 1940s/early 1950s American household is important reading. For me personally, it brought back memories of watching classic TV reruns with my grandmother. "I Married Joan" was a particular favorite.

-

In Avalon, one of my very favorite movies, there is a scene in which three generations of the Krichinsky family gather in the living room to watch their new television. The Krichinskys are in the process of assimilation - Sam, now a grandfather, came to America in 1914. His son, Jules, has brought home an early television. With the tiny screen embedded in a beautifully varnished wood cabinet, the television looks more like a piece of furniture than a revolutionary entertainment device. Switched on, the family’s initial reaction is, to modern eyes, quite amusing. The only image displayed on the screen is a test pattern, black and white, of course, with a slight drone or hum coming from the speaker. Sam’s wife, Eva, quickly states she doesn’t understand the appeal. Nonetheless, the family dutifully sits in front of the television, which silently lights the dim living room somewhere in Baltimore suburbia, waiting for something to happen. A cut, followed by changes in posture among the domestic audience, informs the viewer that the family has been waiting for some time. Suddenly, the screen jumps to life, the Krichinsky grandchildren scramble in front of the screen, and Howdy Doody begins. “It’s Howdy Doody time! It’s Howdy Doody time! Bob Smith and Howdy Do say ‘Howdy Do’ to you.”

Lynn Spigel could have written a book on the powers behind television – the networks, advertisers, government regulators, producers, stars, or programs – but instead chose to look at what happened between the moment people like the Krichinskys brought home a television and began to negotiate its place in the domestic environment and broader culture. This process of accommodation of a strange new media is a particularly interesting event for analysis, and it seems appropriate for Spigel to specifically examine the portrayal of television, both in articles and advertisements, in women’s home magazines. These periodicals not only helped women in particular understand how to integrate and regulate the television in the domestic sphere, but were part of what Spigel calls a “dialogical relationship,” one in which widespread discussions of television as a medium ultimately shaped the final cultural form and role of television. Moreover, however, Spigel demonstrates that television itself helped shape the Cold War nuclear family during a time which, as illustrated by Elaine Tyler May, Americans turned to the nuclear family for a sense of stability and control over a world seemingly teetering on the edge of atomic war. Television certainly offers refuge, but interestingly, it seems to further a process of cultural homogenization while simultaneously walling off the family from the rest of society. Spiegl also examines the restructuring of domestic space around these new electronic hearths, noting how changes in living room furniture and even domestic architecture serve as indicators of the extent of accommodation and homogenization.

In Avalon, after the Krichinsky family negotiates the place of the television in their own suburban home, Jules and his cousin, Izzy, open a small appliance store which begins selling television sets to other families in Baltimore. Soon they can’t keep enough sets in stock, and shortly thereafter they open a large appliance store in an enormous old Baltimore waterfront warehouse, complete with a whole floor of television sets. Having come to understand the role of television within their own homes, the Krichinsky cousins are now exporting sets into the homes of their neighbors. -

A review for my graduate school lit class.

Spigel's book is all about the importance of television in postwar American society. She makes several arguments for the derogation of family life as a result of its introduction into what she refers to as the 'family sphere,' but she also admits that TV made life easier for most families for things like news and national events.

Spigel's main argument is that television, in conjunction with national highway systems, an unprecedented postwar boom, a large number of children and opportunities afforded by the Truman Doctrine spawned American suburbanization and all of the glorious descendants we enjoy today. By putting information inside of homes, families were less likely to socialize outside and we less dependent upon word of mouth.

My favorite point Lynn makes is her notion that television replaced pianos, a cornerstone of family bonding from the Victorian era through the depression. Television, according to her, replaced that central entity and began to degrade childhood interest in arts and music.

Her book isn't entirely negative, though. Spigel also argues that television led to enormous revenue gains and suburban job growth in areas typically dominated by agrarian lifestyles.

Our world evolved from that one and, as we continue to rely on speedy sources of information, I fear we continue to walk the line of 50's children no longer interested in the beauty of music and sunshine.

Oh well, time for Family Guy. -

The book covers a lot of information that I've already gotten from previous classes on Television, American Studies, and Women's Studies. So its a bit general but a good jumping off point if you decide to look into more specific books regarding television and society. Also, not overly jargony. I give it a 3.5/5.

Second reading:

The only thing I'd really like to add to my existing review is about the epilogue. I read up until this section without thinking about when Spigel was researching and writing the book. It becomes apparent when she says "the new machine VCR"---the source is cited 1989. The year I was born. 26 years ago. Luckily, her arguments still hold true. Though the virtual reality mention during her epilogue made me laugh. It sounded like MMORPGs or internet communities in general. -

What is really interesting about Spigel's work is that it isn't just about the programming on television, but the changes to living space that televisions brought to homes. Even more that the radio, the television became the focal point living rooms and it helped to create additional rooms, like a family room and rec room. It became a way to experience the outside world, without leaving the private world. One has to wonder what Spigel would think of the massive home theatre set ups that are available now.

The analysis of the actual programming is...ok. Seeing how it is twenty years since the book came out, things have changed and much of her thoughts on early television were dated even in 1992. Even so, I can never get enough of the crisis of manhood stuff. -

Spigel identifies correspondences between popular discourses and industry practices to examine how television was naturalized as an everyday domestic technology in the American suburbs in the 1950s. A thoroughly researched, well-organized, and well-written work of media and cultural history.

-

An in-depth analysis of the effect television had on the post-war family circle. An interesting read for film students as well as those interested in gender studies.