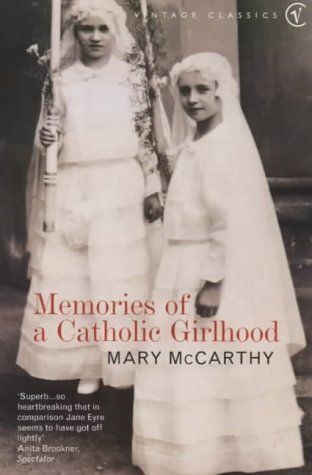

| Title | : | Memories of a Catholic Girlhood |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 009928345X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780099283454 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 208 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1946 |

| Awards | : | National Book Award Finalist Nonfiction (1958) |

Memories of a Catholic Girlhood Reviews

-

Reread

I first read this book in the early ‘80s in a university course on autobiography. We read works that traced the history of the genre and ended with this book. I remember reading Rousseau and enjoying him immensely, but I remember this most of all, perhaps because I was young and it spoke to some of my own experiences. The only paper we wrote for the class was our own ‘autobiography’. Though I no longer have the paper (that’s another story), I remember it distinctly. Each of my siblings (I have five) was the focus of a ‘chapter’ and the professor commented negatively on only one, saying I hadn’t captured one brother as I had the others: I agree; he’s always been the slipperiest.

Earlier this month, after telling a friend the details of a project I’m working on and how I planned on connecting some fictional sections I’d written with nonfictional bits, she recommended I reread this. I took her advice and was startled at how I had ‘stolen’ some of McCarthy’s technique. Did I pull out this method from somewhere deep in the recesses of my mind? Who knows? I couldn’t begin to figure out how many books I’ve read or how many may have influenced me in one way or another. Of course it’s not an exact theft: for only one difference, McCarthy sticks with first-person throughout; even though afterward she explains what’s fictional, that is, what’s not an exact memory.

Times have changed since McCarthy wrote this, so her memoirs (first published in magazines and then incorporated into this book) are not as controversial as they would be now. Times have also not changed. In the opening chapter ‘To the Reader,’ I am struck by the similarity of the hate mail McCarthy received to a type of online commenting of today. The “scurrilous” letters from lay readers, mostly women, (she says the priests and nuns who wrote to her were always gracious) were so similar, she says, they could’ve been written by one person: “frequently full of misspellings,” though the person claimed to be educated; “all, without exception, menacing”; “they attempt to constitute themselves a pressure group”; one even says she is sure what McCarthy has written is illegal.

Since I read this for a different reason than I usually read a book, I’m finding it hard to review. Last night I happened to see a stray review of McCarthy with a low rating that just said “she’s no role model.” I feel that’s missing the point; but, if one wants to judge a work that way, I say this is an honest, brave, true-to- herself, well-written account—and we can all aspire to that. -

Overall, Memories of a Catholic Girlhood presents interesting snapshots of a child, then young adult's life being raised by relatives after the death of her parents. An odd upbringing, but obviously, the only one she has to compare to in her life. Mary McCarthy was only six years old when her parents decided to move from Seattle (home of her mother's parents) to Minneapolis (home of her father's). On the train trip, the entire family became ill with the flu and Mary's parents died. This began her odyssey in search of herself and her place in her family/families.

The story is presented in somewhat fictionalized flashbacks, especially of the early years, based on her memories, with afterwords of corroborations or corrections of some details that arise out of discussions with her brothers with whom she shared the early years in Minneapolis. The years in Seattle are all from Mary's memory and have only her editorial oversight as the boys were left behind by her grandfather Preston in Minnesota and she did not see them again for years.

The title is, in some regards, a misnomer, as Mary fights off the Catholic title early on though it appears to still be part of her. She describes the daily school routines of convent school before transferring to an Episcopalian High School with her Grandfather's agreement. She becomes a very young atheist, adept at manipulating the various systems in which she must live, be it the Preston household, the convent school, the new high school or, apparently, adult life.

I liked the sections where she steps back from the stories and assesses what she has written with an authorial eye a bit less passionately. I think these sections help to make the whole gel more completely and make more sense when we do realize the youth of the original narrator.

This is an interesting memoir, speaking of a long gone era but of some things that still occur today, unfortunately. It has much to offer the right reader.

An ecopy of this book was provided by NetGalley. -

(2.5 stars!)

The essays that make up Memories of a Catholic Girlhood are not particularly memorable, despite being written in McCarthy's wonderful, smart, smart prose. The earlier vignettes - about the loss of her parents to the 1918 flu pandemic, and her awful life in Minneapolis under the guardianship of a ham-fisted aunt and uncle - are fascinating, but once McCarthy moves back to the sheltered, quiet, rarified care of her grandparents in Seattle, her essays become less interesting and animated in turn.

What makes this collection fascinating is not the essays but the analysis that follows each one. Each essay was written for a magazine, and McCarthy frankly picks apart her own memory after sharing the original text, examining what she thinks she fabricated and why, and where she can't be sure what's truth and what's fiction. As an insight into the process of creating prose, and the thin line between fact and fantasy, the analyses are compelling and instructional. I feel like I learned more about McCarthy from her dissection of her own writing than from the essays themselves. -

Better to deposit the children in a Catholic household where they are severely abused and neglected than to let the Protestants get their hands on them. That was the philosophy of Mary McCarthy's grandparents after both her parents died, one day apart, in the 1918 influenza pandemic. Fortunately, when she was eleven years old she was shipped off to her Protestant grandparents in Seattle. While they weren't exactly warm and loving, they were kind and generous and never abusive.

A childhood like this would be enough to make anyone lose their faith, which Mary did at a fairly young age. She never regained it. She writes:

"I do not mind if I lose my soul for all eternity. If the kind of God exists Who would damn me for not working out a deal with Him, then that is unfortunate. I should not care to spend eternity in the company of such a person."

My sentiments exactly. -

Mary McCarthy was such a delightful writer that I could read her writing about just about anything. But what’s most wonderful about this memoir of McCarthy’s early life is the richness afforded by its structure. In this volume McCarthy collected a set of autobiographical essays that she wrote in the late 40s and 50s, and knit them together with some connective tissue, notes to the reader in which she comments on the content and ruminates on the imprecise and unreliable nature of memory. As such, the book gives you three Mary McCarthys: the schoolgirl who is the subject, the memoirist who is writing about her, and the commentator who observes with more distance and perhaps more objectivity. They are, respectively, a sort of id, ego, and superego.

-

I admit that I wasn't sure I would like this book. I put it on my To Read list after someone else gave it a good review, and I am not too sure I actually read the description before I did so.

About 10 pages into it I realized that this book had the possibility to offend and anger me as a practicing Catholic. I made a promise to myself that if I found myself getting upset I would drop it and move on.

I was pleasantly surprised. This is a very good autobiography that tackles the issue of "losing faith" without ever offending or mocking others.

McCarthy finds a careful balance between sharing her personal story of life after her parents died during the flu epidemic in the first quarter of the 1900s and talking about the pivotal moment when she went from devout Catholic to atheist.

I found it very interesting and extremely well written. She wrote this autobiography in the 1950s - well into adulthood. I enjoyed the italicized parts at the end of each chapter explaining what she filled in with "fiction" and what she was certain to be true. It was a very interesting way to read an autobiography. This is something more authors should take time to do really.

It's worth a read, but she is certainly wordy and references a lot of Latin and Greek literature. I would say some knowledge of the classics is necessary to understand parts of the book. She does an excellent job of talking about them without seeming pretentious or like she is trying too hard. -

I first read this in a house Mary McCarthy visited, her Vassar '33 classmate's at Westport Harbor, a grand house with glazed bookshelves containing classics--and McCarthy's Group, which included the hostess as one of the characters. This autobiography appalled and delighted me, a collection of humans almost like a zoo. I read it in a grand corner room above the library, with a few books like Lenin's Lettres à sa famille, and with Cambodian bow (for the hunt) over the fireplace, bow windows overlooking a non-archery foxhunt. The hunt took place over a turnip field that has since given rise to the giant home of a society architect who has a summer home a half mile down the road, on the beach. (Sheer genius to eliminate the travel distances between seasonal homes, though one may speculate that the seasonal change between homes may be…well..fewer, and less dramatic.)

-

What's most interesting about this memoir is how McCarthy takes all the choices she makes as a memoirist and subjects them to scrutiny. She talks about the temptation to fictionalise, the dubious reliability of memory, the reasons to include or exclude information, the implications for truthtelling of shaping life events and memories into a coherent narrative, the compromises and failures inherent in the form. Quite fascinating.

-

Upon finishing 'The Group', my bud Dan Leo recommended several other books by Mary McCarthy. Since I found McCarthy's writing extraordinary, I did a little exploring of her work and settled on this one - with a somewhat misleading title that soon more accurately reveals itself as 'Bad Memories of a Catholic Girlhood'.

Early on in their lives, the author and her three younger, male siblings lost their parents to a flu epidemic. They were taken in by relatives; 'taken in' took on a dual meaning. Whereas their life with mom and dad had been comparatively pleasurable (even if dad was a bit fiscally irresponsible), the kids soon realized they'd basically become third-class citizens in a class-conscious atmosphere of fierce (if taciturn) matriarchs and somewhat-milquetoast (or faux-macho) men.

~ all in the sanctimonious name of religion.

Apparently these collected recollections first saw light as magazine pieces. When they were combined as a book, McCarthy cleverly wrote addendums for all sections save the last. These additions serve, in part, to remind us that memory can be faulty. McCarthy took the opportunity to correct errors of perception pointed out by siblings and others. She also tells us that she received more than a fair amount of hate mail for her 'attacks' on the Catholic church. ~ though, conversely, she received more than a fair amount of grateful thanks from those who informed her that her experiences mirrored their own.

With this work, McCarthy is not exactly taking on the Catholic church per se but, rather, those who follow its tenets - or those who did when she was a young girl. Again and again, she describes people leading lives of rather pointless austerity, who have little room in their hearts for acts of love. These are generally people who have interpreted 'love' as 'tough love', devoid of a loving nature.

Though it's true that Catholic schools - then or now - have not cornered the market on hypocrisy or cruelty, it's also true that they do their part. I'm a product of Catholic school (grade school through college) - and, though I'm no longer Catholic, I can vouch for much of what McCarthy writes. If I didn't experience uncomfortable or unpleasant things as first-hand as she did, I certainly witnessed more than I care to remember. (One of the values of a book like this - a detailed memoir - is that it encourages the reader to look back into his or her own young life for things that merit reviewing.)

As is the case with 'The Group', these memories are impeccably written. Overall, McCarthy is a sharp observer of physical detail as well as character. The only thing that made me a bit sad during the reading is that it seems McCarthy's experiences resulted in her becoming an atheist. While that's understandable under the circumstances, it still seems a sort-of 'baby with the bathwater' thing to do - when genuine things of the spirit have nothing to do with the established (and largely flawed) dictates of man-made 'religious' doctrine. -

Mary McCarthy lost both of her parents to influenza within a week of each other as they were traveling to Minnesota to begin a new life. She was shipped off at age 6 to live with her draconian aunt and uncle. At 11, she was finally "saved" by wealthy grandparents in Seattle.

Fantastic, beautifully written memoir with sharp characterizations and told with rapier-sharp wit. -

Mary McCarthy's autobiographical collection of essays originally appeared in "The New Yorker" and "Harper's Bazaar" between 1946 and 1955. For the book she wrote comments on her essays and addressed the perennial question of the veracity of memory. All of this was highly interesting to me since I am writing a memoir myself.

The McCarthy children, including Mary's three brothers, lost their parents in the flu epidemic of 1918 after an ill-advised move by train from Seattle to Minneapolis during the worst weeks of the epidemic. How would we ever have memoirs to read if young, free-spirited parents did not subject their children to foolish or desperate adventures?

The author is an example of how a highly intelligent human being overcomes adversity and makes a life for herself, though not without emotional scars. Her family included devout Catholics, Protestants, Jews and the occasional atheist. She attended public schools, convent schools and boarding schools.

After a stint with stingy Minneapolis relatives, where the children were practically starved to death, Mary returned to Seattle and lived with her maternal grandparents in a state of over-protection and confused religious beliefs. She became a rebellious, promiscuous feminist until finally settling down to marriage and motherhood, though she never compromised her intellectual pursuits.

After reading only two of her novels and this memoir, she has become one of my heroines, on a par with Joni Mitchell. -

This was an interesting book about the sad loss of the author's parents during the influenza epidemic in 1918 and the circumstances that followed. The four children who survived the illness were parcelled out to various family members where they were treated as poor relations and in some cases mistreated and unloved. The book was very 'wordy', this is perhaps because it was published in 1946 but I don't really think that is the case as many of its contemporaries are far less so. I suppose this was the misery memoir of its day. Interesting but hard going.

-

Going to the incomplete shelf. Too many interruptions. This is a classic-style memoir with some great lyrical prose by McCarthy. Her parents pass and the four children find themselves orphans. Their grand aunt takes them in and the grand uncle is an abusive fool. But throughout the book, Mary interrupts to explain scenes and her perception of what really did happen: imagination or reality? Huh? I keep waiting to get to the real story here but with the interruptions, seems like I'm reading two books...

I'll try again later. -

McCarthy is a good storyteller and this is an easy, absorbing read. Her relationships with women as she describe them here, especially her grandmothers and her schoolmates, are reflected in some of her later writings. She has this odd combination of snobbery/mean-girl-ism and sympathy/insight. She admits to her prejudices and failings, but doesn't really apologize for them, which is both annoying and refreshing.

-

Well, all I can say is thank heavens I am finished with this book. I'll be writing more later but I found this to be a difficult read with a confirmed unreliable narrator. It is difficult to keep going when you question everything. I quickly developed a lack of trust and that is not good when the book is a memoir. More later.

-

Very dramatic! Some reviewers have suggested - not very accurate.

-

La verdad es que da igual que fuera católica o que hubiera sido judía, protestante o de cualquier otra religión. Mary nos cuenta su vida, desde que quedó huérfana de padre y madre, a merced de sus abuelos y sus tíos. El tema católico se trata por estar ella interna, al irse a vivir con sus abuelos maternos, en un convento, pero no es, ya digo, la catoliquez lo que prima en la historia. Sí el sentimiento de abandono, de tristeza, de infancia ahogada. Y también una vista a la sociedad norteamericana de principios del siglo XX.

Se deja leer, aunque me ha aburrido a ratos y tenía ganas de acabarla. -

McCarthy shares glimpses of a childhood marred by the catastrophic death of her parents in the last century's influenza epidemic. McCarthy was five or six, I believe, with three younger brothers. There's Dickensian cruelty here, but also humor and astonishing insight into character and human behavior-- all in McCarthy's gorgeous prose. I always am surprised this book is not discussed more often as a precursor to the memoir movement of the past twenty five years. Between each section, McCarthy includes sections where she explores the nature of truth and memory in the most engaging way. Highly recommend.

-

I do not believe this review of mine will convey most of what I think about this book.

My feeling is that MEMORIES OF A CATHOLIC GIRLHOOD is almost impossible to meet on its own terms almost sixty years after its publication. The first edition copy I borrowed from the public library has, as its copyright date, 1957. The copyright page indicates that several chapters were published in magazines more than ten years before. Inasmuch as McCarthy stresses throughout the book that she is an atheist, a reader in 2015 must bear in mind that in the mid-twentieth century, a serious declaration of atheism brought with it a lot of social condemnation. Mary McCarthy showed considerable bravery in making this public statement.

Remember that Mark Twain, who died only thirty years before the first sections of this book appeared in THE NEW YORKER, kept his expressions of atheism confined to his diary. Bear in mind that the iconoclastic newspaperman H.L. Mencken, who wrote in the 1910s and 20s, was allowed to boast of his atheism because he was basically a humorist, using withering sarcasm in belittling the religious figures of his day. He was also, essentially,in all other respects, a conservative. Although he advocated sexual frankness in literature, he was, in his behavior, as circumspect as could be. He was raised a Protestant in an overwhelmingly Protestant America.(Remember, of course, that his opposition to our entering the First World War caused him to be silenced for a while. A lot of newspapers wouldn't print his articles during the war. His German ancestry worked against him in a xenophobic era. Had he not established himself before the war, he would not have flourished.) We may laugh at religious extremists today, but well into Mary McCarthy's time, someone trying to persuade the public that atheism was a valid stance had to be prepared to be shunned. Bear in mind that when she was growing up, Catholics were targeted by the Ku Klux Klan. Remember that JFK, just three years after this book was published, thought it the better part of wisdom to make a speech saying he'd put his country before the Pope. Mary McCarthy was a woman, of course, in a time when women were still encouraged not to compete with men for work. A female, raised a Catholic, writing a book detailing abuse at the hands of a Protestant step-father, was bound to receive a lot of criticism. It must have been a shock to the general reader of 1957 that the happiest part of the book was its account of the author's loss of faith.

Before the main text of the book begins, and, in italics between each chapter, the author discusses where she thinks her memories, as written, falter. She holds up a mirror to her self-doubt as a writer. This aspect of MEMORIES OF A CATHOLIC GIRLHOOD is remarkably like a typical memoir of 2015. Paradoxically, the self-doubt is more honest than what we tend to read in today's nonfiction. She is warning us that she may be wrong about major facts. While a 21st-century memoirist expects his or her memories to be a haze, McCarthy pulls the reader outside and says, "I'm wrong." This was probably refreshing in the Eisenhower era, but it's reflexive these days. McCarthy was writing this way then, but the innovation doesn't work in the book's favor anymore. A statement to the effect that memory is what it is would have served the writer, the reader and the memoir better. -

(2016 review)

I think what unsettles people about the title is that they assume "Catholic" refers only to the religion. McCarthy's family was Catholic and she attended Catholic school for a few years. BUT (and this is significant), i also think McCarthy is referring to the adjective "catholic" (small c) here.

This time around my favorite chapter is the final, lengthy one about her grandmother. It's a detailed, beautifully descriptive tribute in which she tries to capture their complicated relationship. It seems the truest story in this collection.

After each chapter, McCarthy includes an account of what she knows to be absolutely true in the chapter that preceded, what details she's fuzzy on, or what she flat-out invented to make a good story. It's an interesting way to read a memoir. I love it because it shows the side of McCarthy's personality that is bent on seeking the truth.

************************************************************************

(2007 review)

All these stories are great, and the one in which she tells of her abusive Uncle Myers is, more so than the others, particularly devastating. He's awful but she verbally destroys him, making him out to be the most pitiful character. Her descriptions of what they did as kids for amusement is hilarious; as in, "went to the park to watch other kids ride the ponies, because that was free." -

Picked this one up on a whim while browsing. Imagine my surprise. It's great!

The thing I enjoyed so much about this book is that is doesn't attempt to portray the experience of living the memories it recalls, but presents them with hindsight and a sense of fair mindedness. McCarthy talks about the adults from her childhood more with a sense of pity than resentment, and with the forgiving air of a cultured intellectualism that is both over their capacity, and afforded her by the education their station provided.

The "horrors" (while there are some) are surprisingly few. Pure oddity is what prevails more than anything else, and McCarthy herself admits that the living of it seemed natural and it's only when looking back that she recognizes the exceptional.

Every bit of it entertaining. McCarthy also writes with a simple but constantly self-qualifying prose I love where sentences are constantly folding over on themselves. McCarthy also has a gift of describing things tenderly and carefully.

Blah, blah. All good. Very much recommended.

Also, being an atheist as well, I thought McCarthy's thoughts on religion and her religious life in childhood in the 'To the Reader' section were great. -

Stories of McCarthy's childhood as an orphan raised by two different households. This is only partly "about" the author's experiences: she muffles her tragedy (the early death of lighthearted parents to the influenza pandemic in 1919) by draping it in a child's ignorance, and her bitterness (as a pauper relation, briefly) is lightened by an adult's ironic distance. The book is written at two (really many) points: first as articles published in magazines, and again as commentaries on the original articles. This structure foregrounds McCarthy's interest in the ways that memories are engineered by the present continually to rebuild the past -- always certain, always malleable, often incomplete, and always with her.

-

McCarthy has the widest and most sophisticated vocabulary of any writer I've ever read. These stories are brilliant in her perceptions of what actually goes on compared to what is believed to go on. She's a truth-teller who cuts through the crap and shows things as they really are. She was not favored because she was such a rebel, but favored because she was so creative, which are both sides of the same coin.

It was interesting to me as a Minneapolitan, to read about her years in Minneapolis, even though she was treated like dirt by her adoptive parents. I was happy that she was rescued by her grandfather from the nasty adopted parents.

She's an incredible writer and scholar--imagine falling in love with Julius Caesar, in Latin!

I'm going to read more of her books. -

Me siento culpable por decir esto, pero la vida de la autora no me ha parecido que se preste a escribir unas memorias. Es verdad que esta biografía empieza de manera dickensiana, con la muerte de los padres de McCarthy y ella y sus hermanos quedando al cuidado de unos familiares horribles. Pero después del primer par de capítulos, me parece todo muy normalito: estudiar en un colegio de monjas, perder la fe, un par de borracheras... Nada del otro mundo, vaya. A lo mejor para un público americano que no vive en un país de mayoría católica resulte más chocante o en la época el relato pareciera más escandaloso, pero desde la óptica actual no me ha parecido demasiado llamativo. A pesar de que no me ha despertado mucho el interés, la prosa de la autora es elegante e inteligente.

-

Though I love Mary McCarthy's books, this is my least favourite. Interesting though it is to discover the facts of her traumatic childhood, I have a feeling she never really let go on this one. There is a melancholy throughout the text that actually has a depressive effect - never found this with her other books especially The Company She Keeps and The Group, both of which have just the right balance of humour and pathos. I do still delight in McCarthy's talent at pithy, yet unpretentious prose and looking forward to reading soon her late work How I Grew. Memories is worth reading, just not top of my rankings of McCarthy's canon.

-

I always knew McCarthy's parents both died in the influenza epidemic of 1918. But I never knew what happened to her (and her 3 younger brothers) after that. McCarthy gives us the searing details: the horrid relatives who made them sleep with tape over their mouths to prevent "mouth breathing". (What is with that?) and the terrible food and no toys or friends. How unimportant children were is emphasized, both in the treatment by the aunt and uncle who were paid to raise them, and by the other relatives and the schools. McCarthy is a wonderful writer and this is surely a classic memoir.

-

McCarthy remembers and then fact checks. This memoir changed how I thought about memory and rememory. The idea that one can clearly recall something that is potentially not true at all is both terrifying and fascinating. McCarthy pushed me to consider the boundaries of memory and to accept that we do not always know the "truth" behind a memory.

-

Took me a while to read this, in part because the openjng chapters tell a horrific story of McCarthy’s abuse at the hands of sadistic relatives. The story moves to her subsequent life with her grandparents and her occasionally comic brushes with Catholicism. Not clear that McCarthy ever made sense of her childhood, and book ends on a note of bewilderment.

-

I love biography. Especially when an author can get inside their long-ago mind. When they reveal unbelievably embarassing things about themselves. When I'm exposed to new worlds or history. This is a great book for all those reasons.