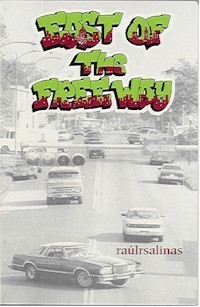

| Title | : | East of the Freeway: Reflections De Mi Pueblo : Poems |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0962350605 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780962350603 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | - |

| Publication | : | Published January 1, 1995 |

East of the Freeway: Reflections De Mi Pueblo : Poems Reviews

-

Note: these notes on the Chicano poet, raúlrsalinas, were first written in 2008 and published in my blog right after he passed away. I am reposting them here, slightly edited for time and correcting typos. Raúlrsalinas's birthday is on March 17; he would have been 79 years old this year.

*

Some notes on the Resistance Indio Poet! raúlrsalinas

Raílrsalinas died on Wednesday, February 13, 2008 at about 9:00 a.m. in Austin, Texas, after a long bout with health problems. Next March 17 [2008] he would have turned 74.

Indio Trails: A Xicano Odyssey Through Indian Country

Raúlr.salinas was/is a Chicano poet who became a writer and activist in prison and continued working on political and poetic causes throughout his life. He came out prison (Leavenworth? Marion?) and was literally exiled to Seattle, being banned from his home turf for a number of years. He returned to Austin, Texas in 1980.

I was fortunate to have met him when I was still very young and an aspiring poet, writer and musician who was mainly a student organizer with MEChA and CASA-HGT.

Raúl spent a lot of his youth, from his 20s on, in prison. Until he was freed on probation around 1970 to Seattle; he was released as a result of being petitioned by a group of Chicano and European American scholars. They helped rescued a deep community poet whose writing and intelligence was shaping the Chicano and cultural-literary movements of the time.

Raúl went from being a prisoner into the arms of a group of writers and scholars, led by one Joseph Sommers and Tomas Ybarra, preeminent scholars who were breaking ground for then nascent and hardly recognized Chicano literature and her writers, poets and cultural workers.

Raul's work had been writing for various prison newspapers and magazines while in prison. He wrote one of the first seminal poems about the chicano movement from prison. Then he was "discovered" by an Italian literary critic/scholar who wrote about Raúl. This resulted in his first collection of poems, a chapbook, titled Viaje/Trip (Hell Coal Press) being published.

Raúl became politicized in prison, sharing jail space with one of the famed Puerto Rican nationalists, at Leavenworth, and living through becoming involved in the prisoners' rights movement of the 1960s. He lived in the time when George Jackson was assassinated at San Quentin and I remember him saying how everyone who was in prison and fighting for their rights inside and out the prison thought they were all like or were George Jackson.

So raulrsaslinas ended up in Seattle, crash landing on the slopes of Mount Rainer -- Tajoma as the Northwest Indians call her -- feeling raza, chicano, mexicano in the isolation of the Pacific Northwest. I met raúl through an older brother who while on an "EOP" recruiting trip passed by our house. Raúl rolled up on the passenger side as my brother drove. He said in his deep, gravelly voice, something like, "your brother says your a poet; we gotta sit down some time and talk about poetry."

My brother later told me about that when they driving through Snoqualmie Pass and other mountain roads (in Washington state), raúl would read parts of his poem, most parts lost, some fragments published, of his love poems to Mt. Rainier. At that time he wore a handcuff around one of his wrists, a sign of solidarity to show that he would not forget the imprisoned sisterhood/brotherhood, los meros meros as Flaco in the northwest memorialized chicanos in prison.

When I was a Mechista student we used to organize delegations that would go on CInco de Mayos, Independence Day to celebrate with Chicano pintos (prisoners) held in McNeil Island peniteniary. We had charlas, brought in small contraband (dulces, lipstick, cigarrettes), played music, read poetry, performed traditional dances and performed in our teatros for all the brothers in prison. I never met raúl like this but I met a lot of prisoners, chicano brothers, who were doing hard time in federal prisons.

Raúl spent some 18 years or so in prisons; both his torment and his savior. Torment because he became a different man than anyone could have expected. A saviour because he became a poet and activist, met other men who were in prison for political reasons, inspiring him along a path of revolutionary internationalism and recovery. He became who he was when got paroled to Seattle, writing, dreaming, being free and not forgetting his debt to society -- that is the debt that society owed him and all his compas, comunidades, our peoples, who were prisoners without being in prison, cons without having been convicted, criminals who were paying this price because they were poor, brown, didn't speak english, had forced out of schools, forced to abandon their dreams and to work, resist, die young, die a spritual death and submit to the system or go to jail for the crime of being working class mexican, Indio, black.

Raúl changed for the better because of what he did while in prison to be free.

Raúl was one of the first internationalists I met within the Chicano political activist community. The first was my brother, who turned me on to the Cuban revolution, sharing knowledge of the Mexican revolution, which my grandfather dug, because that was his story, his youth, his struggles and hard life that he my grandfather did not want any of his children and grandchildren to experience or suffer.

Raul went to Cuba in one of the first Venceremos Brigade, he was really proud of a picture of him and a cubano where he appears wearing a construction hard hat and a red pioneros' bandana about his neck and shoulders. He recruited me to go when I was still a teenager but I didn't go.

When I got to finally went to Cuba he was on the same delegation. He didn't want to hang with the kids when we had free time in Havana and evaded us to get away with his peers, to be with the revolution alone, leaving us to our own devices. Raúl's jaw dropped after members of thed VB delegation reconnoitered at the bus that was taking us back to the Julio Antonio Mella camp when two white U.S. women, who like everyone else, were talking non-stop about their adventures in Havana said the met and had drinks with some old poet named Nicolás Guillén!

Raul had taken off without us with that same goal, looking for Nicolás Guillén, Cuba's national poet, without luck. That evening I got really drunk with some Cubans who were looking for a Mexican. They were university students who had just returned from a stint studying in Mexico. A group of us went into the Havana club hotel (name?), a famous hotel where the club is on the top floor and has a "sun-roof," open to let the cool tropical breezes cool us from the Caribbean humidity. When we walked in, I noticed after a bit a group of men staring at me. I had played in many night clubs and bars in the U.S. and knew the danger and friendship signals. Or thought I did in a socialist country.

I avoided eye contact in spite of noticing they were eyeballing me in a serious way. Then one of them walks over to the table where I am with a group of brigadistas , expecting a fight, even if it was for mistaken identity. He taps my shoulder and asks: Are you a Mexican? I said without missing a beat. Yep. And he said, "!coño! come over here with us and join us for a drink. He explained how they had just returned from Mexico, loved Mexican hospitality and especially Mexico's unflinching solidarity with Cuba in spite of the U.S. blockade.

We talked, toasted every possible relationship between Mexico and Cuba, mexicans and cubans, and got quite drunk. While we're in the Havana club, raul is out and about with his Cuban and u.s. friends, hoping to hang out and talk with his fellow poet and inspiration Nicolás Guillén.

During the day, when raúl dumped us (I was with another chicano poet with me), we went to a bookstore and ran into some poets who were holding a reading close by. The other Chicano poet (Rubén Rangel) and I accompanied them. This was a reading/performance by poets/cultural workers who working with people were called "anti-social." The poets were trying to organize them to contribute to and be part of the revolution. The reading was held at an incredibly beautiful, fancy, regal and huge mansion that used to belong (they told us) to a Cuban gangster, expropriated after the revolution and converted later into a house of culture.

In Cuba, we partied, worked hard, wrote poetry and performed. Raúl led a small group of us into a nearby field with weeds to find chile piquín, to spice up the cuban fare with a bit of hotness.

***

RaúlRsalinas was an internationalist at home. He worked in the American Indian Movement, in the Leonard Peltier Defense Committee, organizing poetry readings, demonstrations, mobilizations, and even smoked salmon sales to raise money for the cause. He participated in the first Long Walk; went to Geneva and other parts of Europe representing the human rights struggles organized by the International Indian Treaty Council, the LPDC and others.

He combined political organizing, literary endeavors and performance, whether it was at El Centro de La Raza in Seattle, with high school, junior high and university students and youth or choral poetry performances. He helped us put together and supported our chapbooks, our concerts and readings.

Raúl led a hard life before he went into prison, during prison and afterwards. He was a man, a human, who channeled his rage into the freedom struggle. Sometimes he would get the best of himself and the majority of time we got to see the best of him.

You have to remember he was a man of his time; living and suffering through the hard times of jim crow segregation, anti-mexican violence, who became politically conscious in prison at the cusp of the jazz revolution, the beat generation and the civil rights movements. He came of age as our community struggles birthed the Chicano, Indian, Black, Asian and other liberation movements in the 1960s and beyond. He was like any poet worth his work in blood and wounds. He was human, contradictory and dedicated to his work as a poet with revolutionary, liberation politics.

That was his primary concern, being a poet who was at the service of communities, of liberation struggles, of being free wherever he found himself.

Over the last couple decades or more, Raúl came of age again: He became a mentor and cultivator of cultural movement and youth. This was a recurring element of his work. That's how I met him, and he related to me not as an older man, which he was, but as a peer and mentor who shared his experiences, good, bad and ugly, with a fearlessness that outmatched his tattooed body.

Even with other crazy poets like us he knew what was real, surreal and that our dreams always had the same roots.

Raúl was multiple raúls: a man, a prisoner, a poet, Indio, activista, cultural center, editor, teacher, publisher, promoter of the good word and cause; inspire-er/conspirator and also nemesis. He made his mistakes in love and politics and paid for them (I am not talking about serving time! Those were not mistakes, but the consequences of the criminlaization of his youth and ours.) HIs goodness, his poesía, his commitment to freedom, will always outlast and overshadow his shortcomings.

I am in mourning for him; I'll miss his letters that he never sent but delivered always in person. I'll miss his telephone calls and other spontaneous interruptions that only raúl knew how to do.

in memory of the living raulrsalinas! -

Raul, take me back to La Loma.