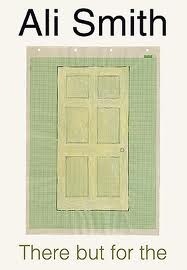

| Title | : | There but for the |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 357 |

| Publication | : | First published June 2, 2011 |

| Awards | : | Orange Prize Fiction Longlist (2012), James Tait Black Memorial Prize Fiction (2011), Hawthornden Prize (2012) |

There but for the Reviews

-

*floating this to irritate the person who irritated me with her comment.*

i did this book a great disservice.

at first, i plowed through it like a maniac, loving every minute of it. then, i put it down for about two days and totally lost my momentum, and when i returned, the shine was off the apple.

completely my fault.

it has been nearly a week since i have written a book review, and this feels like a less-than-triumphant return, but it is fitting - i need to be punished for my weekend hedonism and non-book-reading self. for shame!

allow me the indulgence of an extended quote, because it is something i really liked and it reminded me, thematically at least, of infinite jest:

he thinks about the couple of times he's brought himself off by watching the free porn on the net: two men on the steps of a blue swimming pool, three men dressed as soldiers in a toilet. both times he had to go in search of something else on there afterwards to make himself feel less degraded. the second time he had simply typed something beautiful into the google images box. up came a picture of some leaves against the sun. a picture of a blonde photoshop-smooth woman and baby sleeping. a picture of a bird. a picture of mother teresa. a picture of a modernist building made of shiny metal. a picture of two people sticking knives into their own hands. google is so strange. it promises everything, but everything isn't there. you type in the words for what you need, and what you need becomes superfluous in an instant, shadowed instantaneously by the things you really need, and none of them answerable by google. he surveys the strewn table. sure, there's a certain charm to being able to look up and watch eartha kitt singing old fashioned millionaire in 1957 at three in the morning or hayley mills singing a song about femininity from an old disney film. but the charm is a kind of deception about a whole new way of feeling lonely, a semblance of plenitude but really a new level of dante's inferno, a zombie-filled cemetery of spurious clues, beauty, pathos, pain, the faces of puppies, women and men from all over the world tied up and wanked over in site after site, a greater sea of hidden shallows. more and more, the pressing human dilemma: how to walk a clean path between obscenities

i truly loved the first two-thirds of this book. the dinner party is such a hilarious, uncomfortable, frustrating thing to endure, even only as a reader of it - i never never want to go to a dinner party that is actually like that. they are the worst collection of human beings ever. most of them.

and the part that covers anna and milo's first meeting is tender and beautiful and memorable, and i fell in love with both of them completely.

but the problem with putting this book down is that the narrative perspective changes and any pause is going to ruin the flow, much less a two-day pause with a bleary-eyed foggy return, where you are immersed in a whole new POV and wondering where all your character-friends have gone, and then wondering where you lost an earring in your travels...

it should have a higher rating from me, really, just for the character of brooke - the only hyper-hyper-precocious child character i have ever liked. the book is worth reading just for her interactions with her parents. the fact that i never wanted to throttle her proves smith's skill as a writer.

but - alas - i was a terrible reader of this book. i give the first 2/3 of the book 5 stars, and i give myself 1 star, and that averages out to three stars.

will do better tomorrow.

come to my blog! -

Reviewed in February 2013

There is no doubt in my mind that Ali Smith is a fine writer, a reader’s writer, maybe even a writer’s writer, although I suspect there are writers out there who think she makes it all look as easy as an unmade bed. There you go, people differ hugely in what they rate as interesting or significant, but whatever kind of writer Smith is, she’s definitely my kind, and for the long term. There will be, I hope, many more of her books to enjoy in the years to come. There's a positive thought to treasure!

But what is this book about, you ask, with a title like that? There but for the..what? But for the accidents of birth and death, the accidents of time and place, me here, you there, me now, you then, the inhumanity of man towards his fellow, all of the terrible things which, because they happen to you, can't happen to me. There but for the grace of God go I, as my parents' generation used to remark, in a kind of incantatory and consolatory refrain whenever they were faced with tragedy happening to other people. But the book is also about the fact that none of that matters in the end since in spite of the average reader’s better rather than worse life circumstances, in spite of our living in peace times rather than in war times or hunger times or pestilential times or ‘disappeared’ times, in spite of the advances in technology we enjoy, in spite of life, there is always and only death. There but for...nothing because we all will die. That’s how I interpreted the title. But the title viewed as a whole is only part of what's going on here; Smith wants us to view it in sections too: There. But. For. The. And the sections serve to reveal the whole. The sections allow many interesting things to happen, many big themes to be thrashed out.

For this book is about happenings, and there is certainly a lot happening: bad things, sad things but sometimes miraculously brave things too. Some of the characters make things happen, others are acted upon in a kind of parallel with the artist/spectator relationship. Smith is the artist, manipulating events so that we, the readers, are caught up in the spectacle. To paraphrase herself, Smith catches us at exactly the moment of letting us go, she defies belief and then shows us that we were wrong ever to doubt her. For with Smith, we laugh until we cry and then we cry until we laugh again.

The really funny thing is that I'm reading Proust at the moment and I can't help noticing the similar themes which emerge in these radically different books. The action of this book takes place mostly in Greenwich and one of the major themes is Time. There but for the is, in its own way, a search for lost time. And once I’d noticed this initial parallel with Proust, I found more and more convergences between the two books, and was pleased when Smith briefly mentions Proust, along with Joyce, near the end. The narrative of this novel takes us through forgotten time, remembered time, fugitive time, historical time, chronological time, dream time. The journey through time, just as in Proust, is enabled partly by music and song lyrics, partly through references to the performances of great artists of the past. Gracie Fields in one, Sarah Bernhardt in the other, rhyming couplets in one, alexandrine verse in the other. Mother obsessions in both, a precocious child in both and always, always, time passing, history happening. -

There might have been other ways to write this book, perhaps. Siri Hustvedt, for instance, would have made all the disparate perspectives mirror an overarching preoccupation with the self, nearly indistinguishable from each other in terms of their pedantic, self righteous theorizings. She would have hurled fact after fact which lead up to some grandiose declaration, impatient to broadcast the breadth and depth of her scholastic achievements, her research. A character's whiteness, blackness, womanliness or gayness would have subsumed his/her individuality, and counted as a prime factor in determining their position in the narrative's schema. Not exactly a Russo or Bechdel test fail but close.

But mercifully Ali Smith is no Hustvedt or any other writer intent on bandying about the Big Themes with no effort at subtlety. She unravels her carefully arranged skein of subject, plot and narrative device in a way as to prod our internalized prejudice into emerging from its comfortable hidey hole in to the clear light of day. Busted aren't we? How many of you visualized Brooke as a white yuppie offspring, golden bangs falling across her forehead, rosy cheeks flushed with delight, till she is revealed as a Brooke Bayoude? Pat yourself on the back if you didn’t. Because it is simple enough to presuppose whiteness whenever a precocious child of sunny disposition is spoken of. The Scout Finches of the world are easily conjured up by memory and awareness. And Smith shines the light on this sad revelation.

What would happen if you did just shut a door and stop speaking? Hour after hour after hour of no words. Would you speak to yourself? Would words just stop being useful? Would you lose language altogether? Or would words mean more, would they start to mean in every direction, all somersault and assault, like a thuggery of fireworks? Would they proliferate, like untended plantlife? Would the inside of your head overgrow with every word that has ever come into it, every word that has ever silently taken seed or fallen dormant?

What else does she manage, you ask? Create small moments of such profound tenderness that they knock the breath out of you without ever being glibly sentimental. Call into question our complicity in the perpetually recurring small injustices normalized by the ‘system’. Lovingly dissect the fact of language and art and history wound around each other to produce this layered narrative of our reality. Us and them, you and I, spread out across divides of time and place, engaged in our quiet, quotidian struggles to rise above our worst failings, but converging at some point in a then or a now which may mean nothing in the greater scheme of things but does, all the same. Lost time that can never be regained. The wonderful, beautiful, terrible 'then' - of friendship and motherhood and tenuous bonds between new acquaintances, random strangers - which fades in and out of consciousness, edging closer to oblivion with every passing second but somehow surviving in the end. Much like hope, much like love, much like life.

What else can a reader want? -

Will you remember me in a months time?

Yes.

Will you remember me in 6 months time?

Yes.

Will you remember me in a years time?

Yes.

Will you remember me in 2 years time?

Yes.

Will you remember me in 3 years time?

Yes.

Knock knock.

Who's there?

See, you've forgotten me already.

I used to work at a video store in college. It was a small mom and pop shop, and it was a great place to work. Since it was such a small operation, there were only a handful of other employees and I knew everyone pretty well. So you can imagine my surprise when a former co-worker and I were conversing about the old days, and she brought up a person who worked there that I had completely forgotten about. And when I say completely forgotten about, I don't mean like someone I hadn't thought about much in the intervening years, how are they doing these days? I mean like, I completely forgot this person existed. This is a person I saw three or four times a week for something like a year or more, and I completely forgot they existed. And I'm not even 30.

But that's life, right? How many times have you promised to stay in touch with an old co-worker or a friend who was moving away, and you do, for a little while. But then the time between emails lags a little more, and a little more, and then they stop coming at all, and then you find yourself 10 years down the road realizing you have completely forgotten this person. We're constantly creating new experiences, meeting new people, making new memories, and there's only so much room in our brains. Sometimes things get pushed aside, even things that we really appreciated in the moment. At the same time, there are other things we wish we could push aside and forget about forever, banish to a graveyard with all those old co-workers and classmates, yet, no matter how hard we try, we just can't forget.

That's what There But For The is about. Ostensibly it's about a man who, during a dinner party, locks himself in a guest room and doesn't come out for months. But really, it's about relationships, and they way we simultaneously hold onto some so tightly, while letting others slip through our fingers without giving it a second thought. The central character, Miles Garth, is seen only through the periphery of four characters who have gotten to know him in some limited capacity over the course of his life, and his sweetly tragic personality is doled out in bits and pieces. He is almost a more subdued, British version of Salinger's doomed hero Seymour Glass, due to his coy, unassuming nature and his preference to interact with children than adults, an answer to the premature loss of his own childhood. The four characters whose past interaction with Miles make up the story are each sweet but tragic in their own way, as I would guess all of us are to some extent. We've all had dead loved ones, or been picked on by peers (or, worse, supposed mentors), or dead-end jobs, or other small, personal tragedies that make us human. We all get on just fine, thank you, but it does leave a sadness, lingering just below that surface, that perhaps we can't quite put our fingers on. But sometimes, like a long-forgotten friend, it comes bursting to the surface, and we can't help but be overcome by it. At times like those, we all just want to go into our own little 5x7 room and stay there until we're ready to face the world again. And that's what this book is about. -

I hate to resort to crude Americanisms, but Ali Smith is the motherfucking BOMB. Her latest novel, circa October 2011, shares a structure all but identical to

The Accidental—four sections with little one-two-page prefaces—but also shares its masterful grasp over narrative voice, language, style, humour, and subtly heartbreaking strangeness.

The title refers to the first word in a significant phrase deployed in each section of the novel. For example, in the first part ‘There I was’ is used when the character Anna is speaking to someone about journalism (which can be summed up in six words: I was there, there I was), and later ‘The fact is’ is used by precocious child Brooke for her little book of facts. These words and their significance within the narrative allude to the book’s questions of representation and presentation, both in a literary sense, and in broader notions of reality.

The novel’s four strands revolve around an opaque stranger named Miles who attends a dinner party and locks himself inside his host’s spare room, thenceforth refusing to budge. The reasons behind Miles’s motivation are never made clear, and the event is merely a pull for the four protagonists, each rendered in a breathtaking close third-person style that demonstrates the truly balletic skill Smith has with language. At the heart of this book—and it seems a lot of her work—is a fascination with storytelling itself and how language distorts and enriches our understanding of life in equal measures, and how baffling and wonderful words can be, whether their meanings are monstrous or delightful.

The novel plays elaborate games with chronology in frequent bracketed sections (the structural design of which eludes me) but There but for the is another lovingly designed work of art, bordering on masterpiece, from my newly crowned Favourite Ever Scottish Writer. -

I'm going to start ignoring ratings. Not stop using them, but ignore them, for there is my own and then there are others and neither should have anything to do with the other, really. Humanity gets me but it's the humans that get me in two senses of the word that both don't directly point out the to get in to get. I got this book, someone got my money, somewhere together we're getting.

I thought this book would be harder. I thought I would have trouble. I thought I wouldn't be reading

Women and Men at the time or wouldn't have read all those assonant kerfuffles of hardback and paper so akin, so keep in mind my interest in things like these if you're looking for a similar touch. This book is clean, this book is crisp, and it'll call you and cut you in ways usually preserved in the classics and canon and everything written before what I'm living now. It wears one down when the crowded consensus crows that contemporary literature hasn't a prayer in these heretical times with no dead white males still kicking like it's Manifest Destiny in the fog of a PoMoic puff, so pardon my invoking of a catechism of kiddy-past Catholicism, but this book is a cross, and these are the demons.

The heart of them is this best of all possible worlds complex, this sell-your-soul-for-your-comforts-sake sing-along and nobody cares. People talk of crap literature today and perhaps it's different across the water, it sure looks different when authors like Ali Smith can write this and be respected for it and perhaps not have to worry so much about debt, and socioeconomic machines, and the fact is the face of US literature is being beaten to a pulp by derision, starvation, and shame. Show me a way that any and all authors of quality will be enabled to live without careers or inheritance or windfall propelling them out of the silence at odd and jangled times in this country of mine, and I'll show you hope.

People talk of references as if embarrassed by signs of the world they live in, a world of Millennials making do because they can't follow the pre-privacy pre-privitization pre-pricing of the commons and of faith. You make software engineering the most fertile career, you idolize the Apple and its shiny China factories, you incorporate every digital nitpick into a monstrosity of finance and political machinations and ignore the average age of all these causes in favor of the burgeoning generation to come, but wait. No politics either, remember? Or religion, but seeing as how that last paragraph blew the sentiment to shreds, we'll just have to accept the fact is we are living in a war where following the latest sensationalized third world tragedy from the corner and being grateful for your relative privilege and spankin' new drones does not make you a better person. It makes you free to be exactly as you're told to be, consumerism guaranteed and intellectualism too so long as it's the right type of ideology; so long as you are, too.

Loving this book means knowing the dystopia and how multimillion dollar the begging and pleading to differ in front of the young ones currently is. Loving this book means not blaming the young ones for this they are given, for none of you had a childhood with you in control. Loving this book means effort (living) and pride (self-worth) and a certain measure of who gives a fuck if you like thinking outside of the boundaries of sports and business and screaming your sincerity to the world. Loving this book means recognizing how to characterize people of color by the color blindness in both sight and historical underpinnings of present day context, how to sit down with your week-long emptiness and say hello, how to feel fear at the thought of not tamping down your natural extremities of thoughts and feels and facing the ever-resulting scorn and even worse the lack. Loving this book makes you stone cold in the being of the very few, and knowing that it is worth it. Loving this book means knowing you have my trust to not need the usual namedrops, for this is not a quickfix direction to your next compatible guarantee. Loving this book might mean hating the Internet, but I don't. Loving this book does not mean hating the word pretentious in full knowledge of its reality-wide ramifications, but I wish it did.

There but for the instant we feel it worth living; here's to chasing it now and anon. -

There But For The is stylized, literary fiction. It makes extensive use of:

wordplay

emails

stories

headlines

text messages

conversations

lyrics

handwritten notes

allegory

symbols

The fact is, imagine a man sitting on an exercise bike in a spare room. He’s a pretty ordinary man except that across his eyes and also across his mouth it looks like he’s wearing letterbox flaps. Look closer and his eyes and mouth are both separately covered by little grey rectangles. They’re like the censorship strips that newspapers and magazines would put across people’s eyes in the old days before they could digitally fuzz up or pixellate a face to block the identity of the person whose face it is.

Library data:

1. Middle-aged men—Fiction.

2. Personal space—Fiction.

3. Social interaction—Fiction.

4. Dinners and dining—Fiction.

5. Greenwich (London, England).

6. Identity (Psychology)—Fiction.

7. Psychological fiction.

8. Eyes - blinded, dead, live, terrified, laughing, failing, rabbit's, foul little bloody little black stitches.

9. Children - bright, charming, unthreatening, polite, old-fashioned—Fiction.

10. Prisoners - freedom, security, democracy, human rights.

11. Music - Also: puns; knock-knock jokes; clichés; limericks; rhyming; riddles.

12. Objects - paper, pencil, Moleskine, bike, iPod, mobile phone, clock, door, window, Montgolfier balloon.

13. Cult - sainthood, Satyagraha, media, Anubis, St. Alfege, the eye of that rabbit.

The chapter headings :

Epigraph

The fact is

THERE

There was once

BUT

But (my dear Mark)

FOR

For 29 January

THE

The Epigraph(s)

The essence of being human is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, that one does not push asceticism to the point where it makes friendly intercourse impossible, and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life, which is the inevitable price of fastening one’s love upon other human individuals. —

George Orwell

For only he who lives his life as a mystery is truly alive. —

Stefan Zweig

I hate mystery. —

Katherine Mansfield

Of longitudes, what other way have we, But to mark when and where the dark eclipses be? —

John Donne

Every wink of an eye some new grace will be born.—

William Shakespeare

My own suggestion for an epigraph:

"Nothing so aggravates an earnest person as a passive resistance. If the individual so resisted be of a not inhumane temper, and the resisting one perfectly harmless in his passivity; then, in the better moods of the former, he will endeavor charitably to construe to his imagination what proves impossible to be solved by his judgment". —

Bartleby, the Scrivener by Herman Melville

She unfolds the piece of paper in her hands and she reads again the story written on it.

yes I did Yes. -

Life-as-lived, 'Amores Perros"-turn-of-century multi-structured-prism. Ali Smith is the Virginia Woolf of our times (23% Wilde satirist)--i.e. Modernist! Her brush strokes are irreverent (also British!) in One V. Solid Faulkerian Experiment. Smith evokes the sensation of absorbing everything while reading about nothing; she succeeds in immersing us fully in her deviations from standard plot or character (but remaining faithful to tropes, like the man hidden within the house, the sensitive visionary, the reminder of sin, ie precocious imp child... etc.). She is fantastic.

-

I bought this for the princely sum of 99p which is just under $1.30 in real money. It was a brand spanking new hardback (original retail price £16.99!) for sale in my local Oxfam shop. “What is going on?” I thought, using inverted commas. “All these used skronky paperbacks are for £2 and £3 and here are a shelf of brand new hardbacks seemingly untouched by human hand for 99p. The world has gone mad.”

As it happens my daughter recently began volunteering in shops just like this one, so I asked her what this crazy pricing policy was all about and the answer was : nobody wants hardbacks. And the reason for that is: they’re the wrong shape.

So there you are! Fans of modern literature, get over your sizeist prejudices and grab up these bumper bargains at your local charity shops!

***

I thought I would give Ali Smith another go, as years ago I hated Hotel World but since then it’s become apparent she is beloved by all, so I thought it was just conceivably possible I might have been wrong.

But this novel came apart in my hands as I was reading. No, not literally, but that did once happen to me when reading an old paperback of Where Angels Fear to Tread and made that experience even more enjoyable as the very volume crumbled page by page due to desiccated spinal glue (I hope you never suffer from a desiccated spine, it’s a most undignified end, I had to dump the whole lot in the bin), I mean metaphorically, when I realized how the thing was structured

because at first it was all very bonkers, gushing and whooshing this way and that, whereby this couple invite their friends for a posh dinner and one of them brings a friend and the friend of this friend simply takes himself off upstairs (they think he’s going to the loo) and he steps inside their spare bedroom and locks himself in and refuses to come out or speak to anyone.

At all.

What a pickle!

but I realized that really that was just the big fat HOOK to hang four long shortstories upon like Tales from the Crypt does, Ali Smith is not very interested in why this guy did this bizarre act so

we can therefore file Miles the Guy in the Spare Room next to Norah Winters from Carol Shields’ Unless who sits around on a pavement holding up a sign saying GOODNESS much to the complete horror of her mother or Merry Levov, another radical daughter, in American Pastoral who bombs the local post office or – maybe more specifically – the big KAHUNA of all of these random acts of defiance BARTLEBY THE SCRIVENER by Herman Melville who decides to stop working at his office but refuses to leave and the only thing he ever says is “I prefer not to”.)

So we can dismiss Miles, he is a DEVICE. A kind of vague sympathetic space in the novel.

The four stories are really four character portraits. The first one is okay, that sets the whole scene, and the second one is almost brilliant, because it contains a demonically accurate 50 page account of a posh English dinner party where middle class artsy and brainy types verbally skirmish and get drunker and drunker. This is the best satirical dinner party since The Dinner by Herman Koch and before that Abigail’s Party, a film by Mike Leigh. All of these dinner parties make you squirm to your very bowels and swear you will never never ever go to another one even if Stephen Fry personally comes around and begs you to. At these dinner parties people use language to do to each other what Hannibal Lecter does literally at his.

So writers and film makers like dinner parties. Writers also like old people rambling on and precocious children, a lot, and these two we get in the last 2 stories. Old ladies in various states of mental disrepair (feistiness to taste) can be found in BS Johnson House Mother Normal, Kathleen Rooney Lilian Boxfish Takes a Walk, Bernice Rubens A Five Year Sentence, Alan Bennett The Lady in the Van and you don’t have to look far for many others. Precocious children are all over the place – surely the worst is Safran Foer’s nerve shattering Incredibly Boring and Extremely Long, another bad one is Reif Larsen The Rancid Young Loudmouth TS Spivet and all the Glass Family stories by JD Salinger which are actually good.

There But For The is but therefore the accumulation of four or five of the favourite things writers like to write about. Not for them raindrops on roses and whiskers on noodles, they like 50 page monologues by bright as a button ten year olds and terminal old women with bowels.

Ah yes, Brooke the Ten Year Old does not just monologue, she also has fantastically arch conversations with her parents like this – her father asks her

What are you writing about, spawn of Terence Bayoude? It’s about a man in a room who stays in the room and never leaves it but in that room he has, like, a bicycle, and he cycles three thousand miles on it, Brooke said. What a turn-of-the-century sounding story, her father said. Like Mr Garth? Her mother said. Sounds more Kafkaesque to me than fin de siècle. Fin de cycle! Her father said.

This kid has got no chance. This is how her parents roll :

Your mother and I were having an intellectual discussion last night about turn-of-the-century manhood, her father said. It was because your father was annoyed that I was watching a film called Ronin on TV and that I wouldn’t put it off and come to bed, her mother said… and when I said that I would tell all her students and work colleagues and employers that she prefers, as examples of turn-of-the-century manhood, Arnold Schwartzeneggar and Al Pacino to Proust’s Swann and Joyce’s Bloom, she got quite violent with he and even started hitting me quite hard in the chest area, her father said

So, to sum up : hey, I only paid 99p!

-

THERE

is no there there, Gertrude Stein

famously wrote in 1937, a sentence that loops back on itself in order to question its own grammar. Maybe what she meant was that the first there has no antecedent. But the sentence also pushes out, questions the world, questions the idea of a place in time, a time in place, that exists only because it is not here, relatively speaking.

This novel has a similar trajectory. Broken down into four sections titled There, But, For, and The, it tells an abstract story that questions the meaning of those words. Which may seem slight at first (Duh!), except it's not. Like the puns that the child Brooke is obsessed with, the book convinces us that semantics matter, words matter. And what seems an unlikely story about a man who's locked himself into a room is really a story about how we label our world. Which is really a story about how we think about the world. Which is really about if we can even think about the world (or know it).

Because a pun is basically a mislabelling that creates pleasure. A misnomer. And this book has many. Brooke becomes broke. Miles becomes Milo. Gen becomes Jan. Anna Hardie becomes Anna K. And like a good pun, this book is playful and gives pleasure. It is funny,

BUT

not in a ha-ha way. More in an aha way. There is always a but, isn't there? Actually there are many buts. Time and place, memory, history, a rhyme that jogs the memory into thinking of a time and place (where a man jogs in place, or does he ride in place, on an exercise bike?), the ostensible seemingness of things versus The Fact Is of things, these were all seamlessly (seemlessly?) weaved into the prose with great skill. But

then there were things that made me roll my eyes: cell phones, CCTVs, surveillance cameras, microdrones, celebrity culture, internet porn were all conspicuously annoying in the story. Yes, these are important things to think about, but do we really need to be reminded of the obvious (Duh!)? Come to think of it, have any of these things ever made it into a novel that wasn't trying to show me the shallowness of modern life? I felt like Don DeLillo was breathing down my back. And

though I loved the first two sections, the last two felt weaker, in the voice of the elderly Mrs. Young and the young girl(y) Brooke ("broke") Bayoude. Brooke was tolerable, adorable even, when she would only be precociously naive about something during a tense dinner conversation. But being entirely in her head by the last section was too much for me. I got annoyed. But

I do like the idea of them. Maybe Smith is suggesting that when our collective language breaks down, when we can't name things as they are anymore but only as they seem, when language is "broken", that somehow it is most alive, and most alive to those who themselves are "broken", or superfluous to society, the very old and the very young. Because language, in the normal world, is

FOR

something: a purpose. Communication or business or banter. And when it is functioning it is functional and boring. Like a machine. You're either for us or against us. Zeroes and/or ones.

Old Mrs. Young couldn't talk at first. But when she was finally able to, the words that came out of her resembled involuntary movements she couldn't control. Like her bladder. Animal utterances. Muscle memory. Phrases she knew but didn't mean to say. Like a bird who repeats things that she doesn't understand. But her age is an asset. "The leaving of life, when it came, might well be accompanied by a different seeing" (p. 142). And Brooke, the child, on the other hand, who is yet to find language functional

is also accompanied by a different seeing. She sees words strangely, as a tiger cub does when batting around its first prey rather than eating it. She's curious about language, about the way it works and still fresh to its odd pun-like qualities. Here is where language belongs. Something about history and the long stretched canvas of language that is best kept by the young and the old, the ones who don't matter as much in society, the overlooked ones, the the.

Thus language is made new again through puns and cleverness. You get a sense that if Brooke never completely grows up, but grows older, she could become Ali Smith and write an incredibly clever book like this. The way the storylines connect, the way the wordplay resonates between the sections and the themes, pretty much everything about this novel was clever. But in its examination of words, the novel also examines itself, and the topic of cleverness: what is cleverness for? No doubt a pre-emptive strike against those would-be critics on Goodreads:Then she asked Mr. Garth did he really think there wasn't anything wrong with being cleverest. Top of Mount Cleverest, Mr. Garth said. Brooke laughed. Then Mr. Garth said slowly: the fact is, that at the top of any mountain you'll feel a bit dizzy because of the air up there. Cleverness is great. It's a really good thing, when you have it. And when you know how to use your cleverness, it's not that you're the cleverest any more, or are doing it to be cleverer than anyone else like it's a competition. No. Instead of being the cleverest, the thing to do is become a cleverist.

i.e. the becomes a, from a specificity to a generality, we lose ourselves in the collective. Cleverness matters only in this regard: to connect. Empathy with the disenfranchised. There but for the grace of God go I.

THE

the,

wrote Wallace Stevens at the very end of a poem. That was it. The the.

What kind of ending is that? The lack of an ending. The lack of anything, but a reference to a reference. The part left out of headlines, because it's implied. Area Man Reads Book Writes Review. The part left out is the only part that remains, for Stevens. When you eat an apple, you throw away the core. Man On Dump. No headline has the word the in it, i.e. There is no the there.

Similarly There But For The has a part missing. There But For The WHAT? I want to ask. But the answer would be Exactly! What's missing is the subject of the book, the whole point of it. We're not there at all because we're missing what we're missing, so we're here. The book wouldn't exist if not for the missing ____ at the end of the The.

So the book is about this missing piece, the story without a core, the center will not hold. And by the end of it we've whipped up a lot of cream without anything to put it on. All the pieces connect, but the reader still feels empty, there is no comforting explanation for the mysteries that haunt us (and that's the point). Does it matter? Does it make it less enjoyable? (My answer is no, but your Milo may vary.) We keep waiting for the revelation. The moment of understanding, of purpose. Of of course. Obviously. Of The Duh. -

There, but for the grace of God, go I.

said John Bradford. A sentence merely nine words long, yet easily conveying a quality hard to come by. The ability to understand another’s misfortune when one could ignore it and keep going their own merry way. The ability to reach out to another via an empathetic bridge, instead of only offering sympathy.The humility and acceptance that not every shoe is meant to fit a special Cinderella, being in another’s shoes is a common fate.

There but for the, a novel about a man who locks himself in a room in a stranger’s house - as most descriptions of the book will begin. An act doubtlessly bizarre by any standards of our society. And yet we don’t see any of the characters pose a Why to Miles’ act. Perhaps they understood? For couldn’t Mark have felt the need for a room like that when being stared upon by strangers while he was speaking to his mother, now dead for forty seven years? May be little Brooke would have found some comfort in that room, in being able to hide from being singled out by her teacher - likely due to the colour of her skin. They didn’t know the why, but perhaps, in some indirect way, they understood.

There but for the, a novel about a man named Miles who locks himself in a room in a stranger’s house. Well, not quite. There but for the is also about all the people you know, and have known. From the encounters that have remained special on account of their ephemerality, to those whose constant presence around you has become indispensable. Told from the point of view of four narrators - each of whom have briefly shared one path or another with Miles - we only get a tangential view of Miles. A glimpse of the ways in which he has touched their lives, big or small. We look back twenty years to meet a young Miles who had brightened up one summer for Anna. We meet the gentleman who has been visiting May on every anniversary of her daughter’s death, the two bonded strongly in their shared sense of loss and grief despite having barely ever spoken. While Miles is shut behind the door, the colours he has filled in other’s lives are still visible.

Just like some of the encounters we have with people around us, the few hours we spend with these four narrators, too, are touching in a subtle way. Ali Smith draws characters that don’t take long to become memorable. Another aspect of her writing that stands out is how clever it is, full of smart wordplay and puns. Everything else about her writing - wonderfully subdued and understated. It’s tender and poignant, but never schmaltzy. It’s satirical, but never caustic. It’s humorous, but never over the top. I love that Smith trusts her readers, and doesn’t feel the need to spoon-feed or manipulate them. Each of the narrators are given their own personality and voice. She writes with a great balance and flawlessly, and she makes it look so easy.

The only But I have with the novel is with its disapproval of new fangled technology. Every generation has considered their times modern with respect to the previous one. The very things that they had perhaps denounced as modern day voodoo, have now become inseparable parts of our daily lives. Had it all been merely evil, it would have perhaps drooped and wilted somewhere along the way. There sure are negative sides to many new innovations, but it certainly isn’t all black and white. -

If you're new to Ali Smith and think you might like her (I can easily see that she's not everyone's 'thing'), read her brilliant short stories, or the novels

Hotel World or

The Accidental first. I loved those.

And if you have read all of Ali Smith, as I have, I think you will find that this book is merely okay, even tedious near the end, and that maybe instead it could've been another brilliant short story. Because what feels like excessive padding and way too much language-play (especially with the last section belonging to the precocious 9-year old girl, Brooke, though when she's seen from others' viewpoints, she's a great character) ends up not meaning much at all, which is uncharacteristic of Ali Smith's other work.

What I did end up liking (as with the rest of her work) is the way the story ends, the way it folds upon itself, much like the tight, origami-like paper airplane described in the very first section of the book. The ending led me back to this beginning, but, unfortunately, on this revisit I didn't find as much there as I hoped I would. -

Ali Smith is my favorite contemporary writer, and this book reminded me why.

-

There are things I now know. I now know that rabbits like licorice. I now know that Harold Arlen couldn't think of a middle-eight for the song he was writing, Somewhere Over the Rainbow. But he had a little, badly-behaved dog that kept running away. So he whistled for the dog to come back: De da de da de da de da. And now we all sing: Some day I'll wish upon a star.

But I don't know why Miles Garth left the dinner party and went upstairs and locked himself in the guest room. And I don't know why he finally exited the room. I mean, I would have left the dinner party too. The lamb tangine sounds nice but I choke on competitive erudition and shallow assumptions. But while Miles hibernates we are treated to four people who met him in the past, barely met him. Yet each one was treated to a little kindness. With nothing expected in return. The points of view change, but none of them are Miles'. So we, the reader, become the successive others, left to ask Who Miles was? and How did he change us? I don't do this for a living; I do this for fun. So I don't have to come up with an answer; no I don't. But it was fun.

For an interpretation of There But For The in Proustian terms, see Fionnuala's review. I'm holding off on Proust until a long prison term or the event of French global domination, whichever comes first. Suffice it to say that every page here is rife with references to Time and Memory: I'm standing on time....It's much easier to memorize something that rhymes....Animals, Mark, have no use for nostalgia, Aunt Kenna says. It is not a tool for survival, my darling....It's what I like about handwriting, Mr. Garth said, that it is about time. Hell, the events occur mainly in Greenwich and especially at the Observatory.

The four characters are all memorable, none more so that the precocious 10 year-old, Brooke, who really has a starring role. It is through Brooke that Smith can show off her delightful wordplay. And wisdom. The other three...(Anna, a 40 year-old Ethic Cleanser; Mark, 60, gay and adrift; and May, an incontinent octogenarian needing to flee the nursing home)...have all had Miles transect their lives, always with some unexpected kindness. But it is Brooke who meets him on his terms. They ultimately trade stories, made-up stories with alternate endings. This book affected me more deeply and more unexpectedly than I imagined. -

I just... don't know. I don't know about this book. Believe me when I say that I really wanted to love it. I 'saved' it for some time before beginning, and when I didn't feel much into it on the first try, I left it for a while and tried again. Everything (the premise, Smith's reputation, great reviews in the press and here on Goodreads) suggested it would be a wonderful, even revelatory read, and yet... I mean, maybe I've shot myself in the foot by reading so many books this year. Maybe I've got some sort of book fatigue. I always get confused when I see people reading hundreds of books a year and they're almost all the same genre; endless romance, or endless YA paranormal adventure, or endless murder mysteries. I would never judge someone else's reading habits, but I do wonder how it's possible for people to read the same type of book repeatedly - especially if they finish several per week - and not get bored of reading such similar things over and over again.

The problem with this book, then, is that I feel like I've already read it several times this year. Back in the days when I read about 10-20 books a year, there's every possibility I would have been blown away by this, thought it was an absolute masterpiece. But what I've begun to realise recently is that there's a certain type of acclaimed literary novel that can be every bit as predictable as its trashier equivalent. These books are always loosely constructed around some sort of plot idea but aren't really 'about' whatever that is; they always rely heavily on themes of memory, loss, regret, grief and how we relate to others; the narrator/s is/are usually someone old, or older, looking back and reflecting on events from their childhood and younger life; the meaning and significance of language, how we choose to use it, and the formation of stories about our lives/ourselves invariably play a key role. Examples from my reading of this year alone are:

Great House,

Landfall,

The Blue Book,

The Sense of an Ending,

The Sea,

The Gathering,

The Finkler Question, to some extent

The Corrections and a couple of Paul Auster's books. All of these can, at least loosely, be said to fit into the above description. In particular, The Sense of an Ending and The Blue Book are incredibly similar to There but for the, to the point that they could almost have been written by the same person.

To summarise the story, it's 'about' a man, Miles, who goes upstairs during a dinner party with a group of people he barely knows, locks himself in a spare bedroom, and refuses to come out. This event forms a background for a series of narratives from people loosely connected to Miles. There's Anna, a vague acquaintance from many years ago; Mark, who brought Miles to the party, although the pair had only met briefly before this; May, an elderly woman seemingly facing the end of her life in hospital, whose connections to the dinner-party characters are very slowly revealed; and finally, Brooke, an extremely precocious 10-year-old also present at the party. The narratives are written in the third person, but offer an intimate insight into the characters' thought processes. There are tangents, diversions and recollections galore as the characters explore what their relationships to one another mean, question themselves and dredge up long-lost memories. Brooke's chapter is the best, a lively stream-of-consciousness filled with jokes and puns, witty and clever but, in the end, perhaps a bit pointless.

There is no doubt that Ali Smith is a brilliant writer. Her wordplay and use of language are absolutely wonderful and the characterisation is equally skilful. But I didn't connect with the story, I didn't engage with the narratives, I wasn't desperate to go back to the book whenever I had to put it down; I just didn't like it all that much, to be honest. Sound familiar? It's what I've thought about at least half of the books I listed above. Great writing is great writing, but that alone is not enough to make a great story. Whenever I don't like a literary novel the critics have been raving about, I worry it's because I'm too stupid to truly appreciate it; but I'm really pretty sure that wasn't the case with this. I completely understood everything I was supposed to love about it, it simply failed to elicit any sort of emotional response from me. Sadly, this is another book I very much admired but didn't much enjoy. -

“Imagine if all the civilizations in the past had not known to have the imagination to look up at the sun and the moon and the stars and work out that things were connected, that those things right in front of their eyes could be connected to time and to what time is and how it works.”

Imagine the things in front of our eyes connected to time, to what time is and how it works in connection with memories of past or moments of present or thoughts about the future. The time; dictated by the sun and the moon and the stars and which may be few hours or few days or months or years. Imagine receiving a guest or a piece of paper which reminds you about what time of year it might be, imagine some place you may never have gone and a person you may never have met but whom you met since you went there and which triggered conversations and walk down memory lanes. Now imagine if you couldn’t exactly tell the year or the month or the date or time you recall, would that make a difference in the way you recall them, in the way you feel connected. And what if you lose the perspective of time, of your age and can no longer organize your own thoughts into words.

There But For The fact that the past civilizations had the imagination to work out that things were connected to time that we can, when we want, look back either a few months or years, being a certain age at some point and remember all that we once were or have become over the years.

There But For The fact that we meet people, make relationships and stories, that we have memories of ourselves with them, memories that we jump in and out to ascertain a presence or absence which stirs our minds even when our body refuses to.

This work speaks of this and much more.

On the surface, this is a book about a man Miles Garth who locks himself in the spare room of his hosts one night for months, without any reason. But as we move through the four parts, we realize it is not about Miles but about the people he comes across at different times in his life. How those people, Anna, Mark, Mrs. Young and Brooke, recalling their own memories, are connected to Miles though he is just another person in the story of their lives.

In a language playing with words, infused with wit, satire and puns, Smith speaks of time and memories and humans and places. Through her very clever and profound narrative, we are prompted, subtly, to inquire into one thing that matters most to us – relationships, and how they fare over time and influence us and our times to come.

We are prompted to think of books and stories and what they mean to us.

“Think how quiet a book is on a shelf, he said, just sitting there, unopened. Then think what happens when you open it.”

We are prompted to ask -

WHAT HUMAN BEINGS ARE FOR

And to realize it means different things to different people who have lived different lives over time.

For having a good time RICK

For making the world a better place NOR

For looking after each other MUM

For building things that will last DAD

Ali Smith stuns with the beauty of her style, her play with subconscious bringing to the mind Beckett’s Malone Dies (in FOR) and Joyce (in BUT) but with a brilliancy which is distinctly Smith’s. It is also a satire on the so called acceptable social virtues, on the kind of entertainment which we have today into which people desperately plunge and on the nature of people when they form masses. But above all, this work is a sparkling display of an erudite intelligence which is CLEVERIST. -

"But the fact is, how do you know anything is true? Duh, obviously, records and so on, but how do you know that the records are true? Things are not just true because the internet says they are. Really the phrase should be, not the fact is, but the fact seems to be."

It is incredibly difficult to write about Ali Smith's books. I mean where do you start? Plots are not what they seem. Plots are merely vehicles to convey sub-plots, ideas, sentiments, and impressions of the world around us.

So writing about how There But For The tells about the story of a man who is invited to a dinner party, gets up, and locks himself into a room in his host's house for months is an inadequate description.

Even going on to say that the book also tells the stories of the people around the mysterious hermit guest will not do. Instead, I am going to say that There But For The is a story about underdogs with at least three main characters - my favourite of which is Brooke.

Brooke is a highly intelligent, sensitive child who is bullied by a teacher. She starts to withdraw from her peers and her family and find solace in learning about history.

"So people in authority should be more careful because having your head on a coin doesn’t mean you are immune to history like people are immune to things they have been inoculated against by a doctor. Just because someone is in authority, for example in charge of you, and can get you by the arm when no one will know so that your arm afterwards really hurts, and shout in your ear, so loud so that it feels like a slap and your ear can feel the words in it for quite some time after, it doesn’t mean history won’t happen back to them."

But Brooke is not set on revenge. She is compassionate, inquisitive, and caring - traits she shares with the other heroes in Smith's story.

"What I am feeling is irrelevant, Brooke said, but if you are feeling for all those people, that is an astronomical amount of feeling.

It is an Alps of feeling, her mother said, and what you are feeling is never irrelevant, and I feel an Alps of feeling about that too."

And, yet, even with all those layers of characters and story lines and observing the subtleties of life yet, there is always more to an Ali Smith story than the story it self.

There is always the writing. I love Smith's ability to use words, to play with sounds and meanings and, best of all, to conjure up images which correspond with my sense of quirky humor.

"Now the Queen is sitting in front of a screen. There are a lot of courtiers asking her things and she is ignoring them because she is in the middle of playing Call Of Duty." -

Once there was an anchorite, a cleverist, a once upon a time, and a woman lost in the confines of her head.

“There was once, and there was only once; once was all there was.”

There but for the grace of god go I….

This is about compassion, empathy, understanding, putting yourself in another’s shoes.

Walk a mile in his shoes.

Miles’ shoes. It's about Miles. Miles of Miles. Miles towards Miles. Miles is miles away.

Anna did it. She was overwhelmed in others' shoes. Words words words.“…the woman who had been a university professor said, it is like my chest stops and the words will not, just will not, who had proved unable to finish that sentence and say what it was that the words wouldn’t do, and about whom it was decided by Anna’s superior that she couldn’t possibly be as clever as her summary indicated, being so demonstrably inarticulate. (This woman was finally judged not credible.)"

I keep completing the title in the confines of my head. “… Grace of God go I.” And there is a Grace: “Who was this Grace, who could upend dinnertime, bring her mother to the verge of tears and her father to such paleness?…Grace wasn't a person at all. Grace was a system -- Group Routing and Changing Equipment--which meant that there would be less need for telephone operators, which was the thing her mother had always been.”

[Googled this. There was a GRACE, but it was Group Routing and ChaRging - not chaNging- Equipment. Britain’s telephone system was fundamentally changed by the introduction of trunk dialling. ’…as Subscriber Trunk Dialling was introduced, each exchange was provided with the necessary Group Routing And Charging Equipment otherwise known as Register Translators. What does this mean though? Not the first time I asked that.]

Brook is the cleverist. There is the the. “…there are times you don’t need a the at all, and there are other times you need more than one the.” So: Brook is cleverest.

Reading the book, assembling the words, begins to feel like I am climbing the hill to get to the hermit philosopher - the anchorite -- at the top, where I might learn about his take on the absolute truth and meaning of life. Or at least his life.

He’s grateful for the hot tea.

Words, words, words.

Words will not, the words will not, words wouldn’t do.

Wordplay. -

Oh, Ali Smith. You are an infuriating lover.

I know Frustration is half the fun. And I had so much fun.

But could you please just TRY to write in goddamned paragraphs?

I saw and felt the Disorientation, Stream of Consciousness and Frustration.

But I majored in poetry, and therefore I do not believe but KNOW that space allows for lyricism in all the ways your Matrix layout did not.

It's just a suggestion. Because otherwise I loved it all.

And to be honest, I don't know if I know how to love you without being infuriated at the same time. -

Another great one from Smith. I would recommend this book on the basis of the fantastic conversion on art history in the middle of this alone. Smith's profound and incredibly unique narrative voice is ever present here. Very enjoyable.

-

I was robbed by a British author. Not cool, Ali Smith. The masses were bleating favorably about the novel “There But For The” and frankly the premise seemed so intriguing: A man at a dinner party with a collection of strangers gets up, goes upstairs and locks himself in a spare room -- luckily one with a bathroom, unfortunately at a house not very sympathetic to his vegetarian diet. He refuses to come out for days, for weeks, until he becomes a folk hero and the locals camp out and wait for a glimpse of him.

This is such a great idea. Who is Miles? (Or Milo, as he’s being referred to by the media). What’s he doing in there? (Is he talking to himself? Pacing? Moving from furniture surface to furniture surface, like the star of a super hot one-man show, a dramatization of the circumstances, that is playing at a small local theater?) And mostly: Why did he do this?

We’ll never know.

Instead of capturing the story’s most mysterious character, Smith dances around the outside. She presents short stories about people who have known Miles pre-lock down: A woman named Anna who met him while abroad in 1980 with other students, winners of a writing contest where entrants considered life in 2000. The Scottish misfit is having a wretched time until Miles finds a common interest with her, engages in some witty word-play banter, and provides her entry into the group.

Then there is my favorite, Mark, an older dude who meets Miles while at a production of “A Winter’s Tale” and they find the beginning of friendship while considering whether the mistimed ringtone from the audience ruined the moment or added to it. They end up going for drinks to chat more, and Mark invites Miles to the dinner party.

May is an elderly woman who has had a stroke. She’s seemingly unable to speak, shocked by her own aged body, a little confused and memories are shooting through her mind -- including movies she saw when she was a teen and an old friend of her daughter, who died when she was young. In a last gasp for life, a girl (who is related to the owners of the home where Miles is locked in) takes May on an adventure that doesn’t end well. Miles was friends with May’s daughter and after the young girl’s death he makes a yearly visit to the elderly woman on the anniversary of her death.

The final word goes to Brooke, a tween who is just a little too smart, enjoys puns and history, a quirky and curious daughter of two intellectuals. She also thinks and talks in a rapid flow, stream of consciousness. It’s like, kudos on character development, unfortunately her voice felt like someone was picking at a scab on my brain.

As for Miles? No idea. We learn little about him beyond what these people remember: He was a kind teen, a good conversationalist, a thoughtful man and a vegetarian.

There were times when I liked this story. To be fair, each of the short stories is an interesting slice. And the dinner party hosted by Gen Lee is a kick. She and her husband invite a bunch of mostly-strangers and then see what happens. It’s just something they do. This time they’ve paired smart and articulate neighbors with a man Mark has secretly been banging (and his wife) and a few loud mouth idiots who hate art. The result is the most uncomfortable dinner party, you’ll actually squirm, in the history of placemats.

There is also some commentary on becoming a pop icon. The people gathered in the yard, selling Miles-themed T-shirts and psychic readings and holding signs. Gen Lee, the homeowner, first extremely put out by the intrusion, then finds ways to turn it into a money-making venture. But these little nuggets are few and far between tedious passages.

But the elephant in the room, or the unwanted guest in the room, is Miles. There are, admittedly, a lot of reasons to lock oneself in a stranger’s spare room. We’re all just a single impulse-control glitch from doing some pretty uncharacteristic stuff: punching the accelerator, shoplifting cheap lipstick, chopping all our hair off. Or maybe he is exhausted. Like my friend Hank used to say: “Who wouldn’t want to hole up in a padded room and play some balloon volleyball for awhile?” Maybe he’s on the lam from the mob or an overbearing mother. The point is, there is no right reason. And that bugs.

You know what this is, Ali Smith? You lured me to your store on a snowy night with the promise of selling me the TV I wanted at an inexpensive price. But when I got there, you didn’t even have that TV in stock. Blerg. -

There is a story here

But it is swaddled in word play

For these brain exercises help to force the mind open, and

The fact is, “…sometimes what’s real is very difficult to put into words.”

A unique, alternatively frustrating and delightful reading experience. It felt very personal, like I could see myself in each of the characters. Smith is razor sharp, witty, and imaginative, and covers lots of ground here, particularly social issues of acceptance and stereotypes and what it feels like to be an outsider. It feels sort of, I don’t know, like being alone in a room while attending a dinner party. -

What was wrong with me when I first read this? I still prefer other Smith novels but it’s far from bad.

-

If you played a drinking game while reading this awful novel—taking just a swig of beer for every time the word 'says' is said, you'd be dead. D. E. A. D. No joke. So I wouldn't advise it. I'm convinced that a quarter of the drab content (79,360 words in total apparently) consists of says/said. Is Ali Smith allergic to variety?? Anyway. Here's a helpful hint to the author: when a character asks a question, have them ask it. Don't have them SAY it! This happens constantly. Illogical and irritating. What in the world was she thinking? Or the editor, for that matter? I mean, it is MADDENING. And you'd probably die from taking a shot for each time the phrase 'the fact is' is incorporated into the proceedings. Don't believe me? Read it or listen to it and you'll see. Scratch that. Please don't subject yourself to the pain.

Man alive, I felt sorry for the narrator. I really did. There but for the is an inglorious dumpster fire of pointless mundanities and soulless repetition. The high level of agitation I felt while getting through this thing is staggering. Almost beyond an earthly feeling, honestly...merely getting to the finish line gave me a disgust only akin to seeing a grossly obese woman—equipped with ill-fitting jeans and an exposed belly that just will not quit—shopping at Wal-Mart, also known as the epicenter of human scum. Yep. It's that bad! I can proclaim with utter confidence that Ali Smith isn't a good writer and I am more than surprised that a book like this would even get green-lit. Pantheon published it? An imprint of Random House (back then, that is)? Wow. There is no God. Just kidding...there is (sorry, atheists!). I'm so ashamed that I wasted precious hours of listening time on this woefully uninspired and grammatically incorrect offering. Pass on this wack trash. -

This is another one of those books getting good reviews, but for me, it didn't live up to the hype. This isn't your typical book in that there's not a plot per se. The author sometimes does away with punctuation and linear notions, and even though it centers around Miles Garth who locks himself up in a guest room during a dinner party, we never truly learn about him or his motivations.

Instead, we get the perspectives of four different people who had a brief interaction with him. Mostly, each narrative is about their lives, and some go on for too long. I even wondered why elderly May was included at all until after a (long) while, it became clear.

Smith indulges in some witty wordplay, but sometimes her writing is strange. I found myself skimming at times because I was bored. I'm sure I missed some of her clever tricks with language, but I don't have the desire to go back and look.

There, I'm done! -

Wow. I just want to hug this book. That incredibly rare thing, in the 2010s, a totally contemporary novel that isn't cynical or bitter or cute. Clever, yes. Very.

What's it about? I'm not sure I can articulate an answer. It might be about martyrdom. Or it might be about losing one's humanity, and trying to get it back. Or it might be about boredom and frustration and loss. It might be about horrible dinner parties filled with dreary backward privelged snobs. Or it might be about compassion, fellow-feeling, paper airplanes, music and love. Whatever it's about, it's about us. -

Comprei este livro apenas porque gostei do título (não costumo fazer isso mas, às vezes, tenho que ser inovadora...) depois, arrumei-o e esqueci-o. Há dias, quando li uma crítica (com cinco estrelas) ao último livro de Ali Smith, Outono, lembrei-me deste "coitado", que tinha encafuado no "monte dos não quero ler isto". Pois... podia lá ter continuado... li metade e... oh, céus! já me esqueci de tudo! Bom... acho que eram só umas letras que de tão aborrecidas não passaram disso: letras...

Mas creio que me vou redimir com Outono, de que já li umas páginas muito bonitas... -

Cominciamo dal titolo: C’è ma non si. Un titolo irrisolto, che penso sia inutile provare a completare. Io ci ho provato più volte, senza convinzione.

1) C’è ma non si vede. Miles Garth, invitato a un pranzo da un amico omosessuale in una casa dell’alta borghesia inglese, a Greenwich, improvvisamente. nel corso del pranzo, si alza da tavola, sale le scale e si chiude in una stanza. Rimarrà lì per giorni, senza comunicare con altri tranne una bambina, Brooke, un fenomeno dall’intelligenza oltre la media, abbastanza saccente ma di certo personaggio di spicco del romanzo. Miles rimarrà segregato in questa stanza per giorni, protetto da una tendina alla finestra dagli occhi di giornalisti e di curiosi che si appostano sotto casa per riuscire almeno a intravvederei il fenomeno. Miles c’è, nessuno lo vede ma nessuno lo vedeva anche prima che si chiudesse in quella stanza, nessuno lo conosce, sa del suo passato, anzi ora che ha compiuto questo gesto inconsueto tutti parleranno di lui, si scriveranno articoli o si faranno servizi giornalistici su di lui, ma Miles resterà un fantasma. Le parole costruiscono il mondo, ma non le persone.

2) C’è ma non si capisce. Il romanzo è stravagante, molto sperimentale, di difficile comprensione, con picchi di genialità letteraria e altri di noia, con continui flussi di pensiero di una molteplicità di personaggi, tutti collegati con l’evento centrale, quello di Miles, ma ognuno con la sua storia. È diviso in quattro parti, corrispondenti alle parole che compongono il titolo, in ogni parte interviene un personaggio che ha “conosciuto” Miles, ma ognuno parla di se’ stesso, per cui spesso si trovano difficoltà a collegarlo con la storia principale. E poi c’ Brooke, la ragazzina superdotata, con i suoi giochi di parole, gli enigmi, le battute e le barzellette basate sulle ambiguità linguistiche, l’unica che si avvicina a Miles così, giocando con le parole.

Per la maggior parte della lettura mi sono annoiata, ho capito poco, poi magari ci sono stati dei passaggi veramente interessanti, ma purtroppo il mio bilancio finale è negativo, pur capendo i lampi di genialità della scrittrice. Per una lettrice “classica” ( o tradizionale o limitata che dir si voglia) come me, questo romanzo è troppo, troppo fuori dagli schemi, troppo contorto. -

I don't know that anyone but me will find this of interest, but I'm going to use this space to keep a reading journal/diary instead of a normal review. Warning: This is likely to contain spoilers.

----------------------------------------

July 2: Took the book off my shelf and put it near my bag for work. Had every intention of starting it, but was too tired from getting up way too early, bike commuting, etc. Feeling old. Did lovingly turn the book over in my hands several times, admire the cover design, and peel off the used price sticker.

----------------------------------------

July 3: Started this on the 40 min. train ride to work. Smitten at once. From the intro quotes to the brief, odd opening section (let's call it Before There; would that be Now? Here?). "Fact is, imagine... " Reality sprung from the mind. In just a few pages, Smith take two flat images (the idea of a censored face/person usually seen in a photo or video; the flat piece of paper) and gives them dimension/life (image become "real" fiction character; paper becomes folded airplane with dimension, perceived "weight," and motion). Feels like a metaphor for writing/storytelling to frame what may follow. Only 15 pgs in but already dog-earing page corners, underlining passages, and making little pencil notes to myself. Brain off on flights of fancy. Single lines and paragraphs operating on multiple levels with Smith.

----------------------------------------

July 4: Read some more on the train ride home. Finding the characters quite funny. I think I actually laughed aloud with the young girl Brooke piping back into the conversation, hidden behind the couch when she was supposed to have gone "elsewhere" (is that the same as "over there?"). Find myself ruminating on the word "There" and how it's quite specific for such a word that is vague without context (especially when talking about location). E.g., When we were there, Over there, There by the... It can function as multiple parts of speech, but is almost always serving as a substitution or vague modifier. A stand-in. A substitute. A sign of a sign a few steps removed from the signifier. (My internal editor screams for someone to step in and stop me from these type of ramblings... a this, a that, another this... how my wife lives with me is beyond my comprehension but not my gratitude.)

Last night I really wanted to read some more, but fatigue, the Internet, and the U.S. vs Jamaica Gold Cup game distracted me. I've begun to see so many things as a trade-off: If I do X, then I will have 35 minutes less reading time. Part of me wants to maximize time efficiently and part of me yells in McCoy's voice from Star Trek: "Dammit, Marc, you're a human, not a reading machine!" But am I... ?

Ahem... back to the book. Loving the word play. Smith seems to have this genius way of integrating important points about technology/contemporary life so seamlessly into the narrative that you almost miss these huge revelations. Right now, I can't think of a better writer I've read who is able to transmit and leverage the play/confusion/dynamic at work among writing, reading, and speech. Thinking here of three specific instances: 1) communicating subtly to the reader that Brooke is black with one word ("But it was a white woman... who came to the door" letting the reader know the child's initial appearance made Anna expect a non-white adult to come greet her; Gen, the white woman, later drops a line about Brooke's parents not actually coming from Africa--again, there's a leap here that the writer is invited to take on--this assumption that one would have expected the parents to have come from Africa; both these convey more about how these characters judge and interpret the world and race than they do anything about Brooke; 2) the way a person talks about stereotypes with Gen making some sort of general stereotype comment---positive and negative---about "gays" every time she makes reference to the dinner guest, Mark; and, 3) how we try to interpret, or how we misinterpret, what we hear: Gen is trying to share what she thinks is a very witty acronym, "O--U--T," but Anna hears "oh you tea" and so does the reader because that's how it is written to put us into Anna's perspective. All these things are minute, tiny details, but they all work to great measure in Smith's writing. It would be a great disservice to Smith were I not to point out that in addition to all these details and technical wizardry, her writing is fun and enjoyable. Technique and concept without skimping on the performance!

----------------------------------------

July 5:Surprised to find how endearing I'm finding Miles's character. Because he's first presented to the reader by Gen and seems to upset everyone's life by locking himself upstairs, which then also interrupts Anna's life, I disliked him without ever realizing it. That is, until we start to get a little of his backstory and then I found myself surprised at his charm and wit, as well as that he genuinely seems like a "good guy."

I don't particularly like to break the reading flow of fiction by looking stuff up as I'm reading. The downside of this is sometimes forging on without context or knowledge that I'm lacking (e.g., what a certain word means, what a reference to history/art/another book might mean, etc.). I normally, mark such words or passages for later reference/research. Sometimes I go back, sometimes I don't. In this case, Gen ignores Anna's last name (Hardie) and refers to her as Anna K. Smith makes explicit the Kafka reference but it also invokes Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, and, possibly the more contemporary Anna Ks (neither of which I was aware of, but both of which came up as top Google hits: Anna K the Ukranian designer and Anna K the Czech singer). Do these have any relevance? Peripherally, maybe.

There's just a brief line in the "There" chapter when Brooke skips across the street where Anna seems to imply that she was once responsible for a child or something bad happening to one... ? It's vague and brief, but I'll be curious to see if this comes up again. Smith seems like too detailed a writer to not have a purpose for almost every word she uses.

The absurdity at the heart of all this (that you would just let a strange guy stay locked in your house and continue to feed him) is just barely believable because of Gen's obsession with her house/architecture (no way to get Miles out without damaging the historic door) and her social standing. I'm not sure a lesser writer could pull this off. I'm also not sure Smith can pull it off, but for now, I'm buying it.

----------------------------------------

July 6: Got news yesterday that a family member's chemo is not working. Tumors still growing. Makes reading feel like an indulgence. Like there should be some sort of moratorium on personal enjoyment of any kind, much less exploring fiction. And yet I think in reading we are often exploring life at a deeper more emotional and intellectual level than we do during most of our day-to-day existence. Especially because fiction puts you inside of another's head in a way that is impossible in real life. You simply cannot peer into another person's thoughts and feelings the way writing allows. Which makes me think, thus far (I'm about halfway through the "But" chapter), this novel has suppressed a lot of the emotion with humor and wordplay. There's obviously a kind of ennui or spiritual dissatisfaction at work here with the modern age, with the jobs these characters have, with their relationships, etc. But for now, this sort of hovers above or below actual events and dialogue without really being explored. I sort of suppose that's where general dissatisfaction sits most of the time in real life, too.

I found the transition to the "But" chapter rather abrupt, almost like I was starting over reading a whole new book, despite that it's just a different perspective. I was so fond of the dynamic between Brooke and Anna, that I found myself almost disappointed... missing them. So it took me a bit to switch gears and sort of adjust to the new rhythm (like I had been playing double dutch and everybody left and instead of picking up a single jump rope and swinging it myself, I was still waiting for the two ropes to start swinging again; you know, the normal double dutch memories you have while reading, right? what?!! not sure where that reference came from... ). The dinner party interactions are hilarious. More play on speech/expectations with even Gen's name being spelled differently (Jan, Jen) depending on which character's perspective is presented. Lots of awkward race issues/references just prancing around the table.

----------------------------------------

July 7:Not too much reading today... maybe 20 pages. Thrilled by the U.S. women's World Cup victory (a brief bask in the escapist fantasy sport provided where merit rules, justice is mostly immediate and fair, and women got to own the day). Still loving the ping-ponging dinner table dialogue as the topics and puns reveal more about each character and the increasing inebriation levels ratchet up the tension. Here I was commenting on the suppressed emotional aspect of this novel and we find Mark's mother committed suicide. After using the restroom, he overhears the other guests talking quietly about this and him---it takes him back to when it happened when he was 13 and the other children whispered behind his back. I needed to take a break right around here as it took me back to when I was 8 and my mom died (kidney disease complications, not suicide). Makes me wonder whether Smith lost a parent or sibling at a young age given how well she captures the alienation this creates for an adolescent. Maybe she's just that amazing of a writer. It causes a kind of split like one is now marked. Before there was everyone and that included you. After, there is everyone and then you. Like you're in the same room with everyone else, but there's a sheet of see-through glass between you and them. Thirty-five years scar tissues over the pain and grief, but I'm not sure the divider has ever disappeared. Mostly, it's in one's head, but the disclosure also changes how other's see you. In Mark's case, the suicide makes it a much bigger deal/divider.

That Richard... Man, he's a dick.

----------------------------------------