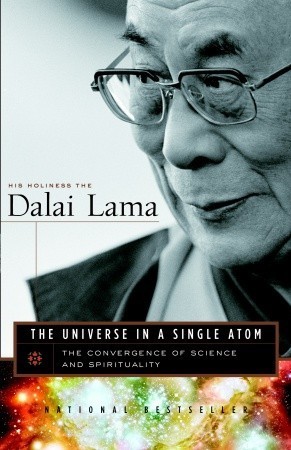

| Title | : | The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0767920813 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780767920810 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 216 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2005 |

After forty years of study with some of the greatest scientific minds, as well as a lifetime of meditative, spiritual, and philosophic study, the Dalai Lama presents a brilliant analysis of why all avenues of inquiry—scientific as well as spiritual—must be pursued in order to arrive at a complete picture of the truth. Through an examination of Darwinism and karma, quantum mechanics and philosophical insight into the nature of reality, neurobiology and the study of consciousness, the Dalai Lama draws significant parallels between contemplative and scientific examinations of reality.

This breathtakingly personal examination is a tribute to the Dalai Lama’s teachers—both of science and spirituality. The legacy of this book is a vision of the world in which our different approaches to understanding ourselves, our universe, and one another can be brought together in the service of humanity.

The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality Reviews

-

very few people are able to give me hope about mankind and our future as a species. the dalai lama delivers that and so much more in all his books, but this one stands out to me because of my interest in science, and especially my fascination with (if complete misunderstanding of) the universe and quantum physics, etc. this book contains all those big universe questions that are usually way too scary to ask (where did time begin? how big is space? what existed before the big bang?) but presents them in conjunction with religion, and not in contrast to it, like pretty much everyone else likes to see those 2 institutions. this is the kind of book where I read 10 pages, then have to close the book and just think for about a half hour, then pick up and start reading again.

-

This is a brilliant book. The Dalai Lama's theme is that science's emphasis on non-personal, "third-person" study and religion's emphasis on "first person" experience and awareness could be complementary.

If you have heard the Dalai Lama speak in his non-native tongue (English), he is a fantastic personality and he smiles a lot, but his communication is limited. It is a pleasure to read his ideas written first and then translated into English. This book reveals a mind that sparkles with wit, intelligence and an ability to pierce through to the heart of an issue.

He tells the story of his discovery and fascination with Western science. He writes of Buddhism's need to update some of its teaching methods and mythologies in the light of mankind's recent discoveries. He also writes of science's need to address issues of personal awareness and the need to be more open-minded concerning an attitude of total materialism. He also points out how akin Buddhism and science really are, as they have applied similar experimental methods to study awareness and the material world respectively.

Throughout, the Dalai Lama's logical process is a pleasure to read, and he comes across as always being open to new input, striving not to color it with preconceptions. This book is highly recommended to anyone interested in the relationship between science and religion. -

A thought-provoking analysis and exposition on why the subjective, first person investigative methodology of spiritual tradition without its fundamentalist trappings and the objective third person investigative methodology of scientific tradition without its reductionist trappings are both indispensable and must go hand-in-hand if we are to fully comprehend reality and genuinely alleviate suffering. The ease and sharpness with which the Dalai Lama draws parallels and acute phenomenological similarities between modern scientific disciplines like cosmology, quantum Physics and neurobiology and the foundational tenets of the Buddhist spiritual tradition and the epistemological and ontological bricks and mortar of Buddhism that were put in place by Indian logicians like Nagarjuna, Asanga,Dharmakirti and Vasubandhu - was the most captivating part of the book for me.

That isn't to say the exposition was very lucid(atleast for me with no prior knowledge of Buddhist epistemology) - but with some application you could think them through and self-verify and assimilate. The book also has a lot of autobiographical snippets on the Dalai Lama's troubled political life, the daily rigors of his contemplative practice, and interesting details from his meetings with several other world leaders and scientists in Dharamsala and elsewhere.

Overall an immersive and appealing read, which has done enough to get me looking to read more of Dalai Lama XIV. -

This book might seem a strange reading choice since I am an atheist. During my years of life and travels around the world, I have found that of all the world's multitude of religious beliefs it is generally Buddhism that seems most comfortable with the concept of a coterminous relationship, if not a synergistic symbiosis, with science. This is not meant to imply that Buddhists make better scientists than say a Hindu or a Muslim, rather that the religion itself seems comfortable with the concepts of science. Other religions, primarily Christianity and Islam, have had a contentious and oft abhorrent relationship with science. Thus this book was an interesting insight into how a very religious man, the Dalai Lama, views science.

Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, has had a very interesting life. After having to leave Tibet due to the Communist Chinese invasion, the Dalai Lama had opportunities to meet and study with some eminent scientific minds. This book is his attempt to explain how a Buddhist monk entered into the world of modern science and concepts such as bubble chambers, particle accelerators and quantum physics.

It is not often, though there are some Jesuits I can think of, that I hear a religious leader express such comfort with the reality of science. He admits that this is not an attempt to unite the two spheres. They can not be united as one is the realm of myth and belief, while the other is an empirical discipline (or multi-disciplinary if you wish to look at all the various specialties of science) meant to explain how the world,I prefer the term reality, around us truly works. What I appreciate about the Dalai Lama's book was his very unassuming and simple take on many of the more esoteric concepts. He admits that his, knowledge of the mathematics underlying the science is poor. So when the scientists explained things to him they used general concepts which would be readily understood by a Tibetan monk and his translator. That's fine, this is not a technical book at all. It attempts to juxtapose traditional Buddhist thought with rationalism. It's the Dalai Lama's disarming honesty, humility and respectful tone that truly drew me to this book.

Rare is it for a major religious figure to say the following:

"...scientific investigation proceeds by experiment, using instruments that analyze external phenomena........if science shows something to exist or to be non-existent (which is not the same as not finding it), then we must acknowledge that as a fact. If a hypothesis is tested and found to be true, we must accept it. Likewise, Buddhism must accept the facts-whether found by science or found by contemplative insights. If, when we investigate something, we find there is reason and proof for it, we must acknowledge that as reality-even if it is in contradiction with a literal scriptural explanation that has held sway for many centuries or with a deeply held opinion or view."

That last line would be considered anathema, if not outright heresy, by many of the world's leading religious leaders. They fear science and thus have a confrontational view of it. I found no such undercurrent in this book. The Dalai lama makes clear that science is reality, though there are elements such as quantum physics that have some elements of spirituality about them. This book then shows how certain aspects of Buddhist thought, and the various schools of the philosophy underlying the lore, have been able to find some similarities in broad concepts, especially in the field of quantum physics.

In the end this book gets a 3 star rating because while it is an interesting story about how this Tibetan monk was introduced to the world of science and his attempts to balance the modalities of both types of thought. But, in the end I find the usefulness of trying to justify any particular religion and that religion's dogma/beliefs to actual science as about as useful as discussing how the Force from Star Wars "works" in or with science. Well it doesn't. At all. -

The Dalai Lama Discusses Science

For many years, I have belonged to a Sutta study group in which we have read many of the key texts of the Pali canon, the earliest of the surviving Buddhist scriptures. We recently read the famous text (Sutta no. 63) in the Mahjima Nikaya, the mid-length discourses, in which the Buddha tried to discourage certain kinds of speculation by offering a simile based upon a poisoned arrow. If someone is struck by such an arrow, the important thing is to have it removed rather than to worry about the type of the arrow's wood or feathers, the clothing worn by the person who shot it, etc. The Buddha suggests that those who worry about certain metaphysical questions, such as whether the world is finite or infinite, whether the world is eternal or transient, or whether the soul is separate from the body or part of it, are like those people who ask irrelevant questions about the poisoned arrow rather than try to remove it as expeditiously as possible. This simile to me seems to capture something important about the relationship between Buddhist spirituality and certain scientific questions, and it encouraged me to read the Dalai Lama's recent book, "The Universe in a Single Atom."

His Holiness the Dalai Lama's eloquent book in fact discusses this enigmatic Sutta together with the divergent interpretations it has received in Buddhist thought. Difficult as the Sutta is, I think it captures a great deal of the Dalai Lama's message in his book, both in his teachings themselves and especially in the tone and manner with which the Dalai Lama conveys his teachings.

The Dalai explores the Sutta I have mentioned in an appropriate place -- in the context of a discussion between the relationship between Buddhist thought and the big bang theory of the origin of the universe. The Sutta and the discussion suggest to me that spiritual questions have an urgency and immediacy of their own, notwithstanding scientific findings. But for me, the most revealing parts of this book were not the sections in which the Dalai Lama discusses the relationship between Buddhist thought and specific scientific teachings. Rather, I thought the most moving discussions were in the opening chapters and in the conclusion. In the opening chapters the Dalai Lama offers some personal biographical information about growing up in Tibet, his monastic training and teachers, and his budding interest in mechanical and scientific subjects. He describes with obvious affection the many Western scientists he has met over the years and how he has responded to what they have taught him. He also tries to draw a distinction between scientific study, which is based upon repeatable, empirical observation and theory -- what he describes as the standpoint of the "third party" and introspection and the search for meaning, which is subject of spirituality and of creative and altruistic endeavor. Science and spirituality frequently interpenetrate, for the Dalai Lama, and have much to give each other. He expands upon this discussion throughout his book and in its conclusion.

In successive chapters of his book, the Dalai Lama discusses, quantum physics, the big bang theory, and evolution. He frequently draws parallels between the results of contemporary science and the results of Buddhist thought. In some cases, he points out that scientific discoveries invalidate certain crude assumptions about the nature of the physical universe found in early Buddhist texts. He candidly recognizes that where specific scientific findings conflict with a Buddhist teaching, the Buddhist teaching must give way. But in other cases, the Dalai Lama is somewhat critical of scientific theory. Thus, the Dalai Lama seems to suggest that the theory of evolution takes too little account of karma -- the nature of consciousness and intentionality -- that he believes necessary to a full understanding of the world. In my opinion, these criticisms of evolutionary theory are unnecessary to the weight of the Dalai Lama's message to look within, to study consciousness and to develop wisdom and compassion. In the process of discussing evolutionary theory, however, the Dalai Lama gives a lucid discussion of kamma, distinguishing it from simple mechanical causation of from the fatalism with which it is sometimes confused.

The strongest scientific discussions in the book are those of the last several chapters where the Dalai Lama discusses consciousness, as developed in Buddhist texts and in the practice of meditation. He suggests ways in which scientists working with the brain and with meditation practitioners can interact in valuable ways that complement their respective practices without denying either of them. Because these discussions of consciousness and introspection involve subjects the Dalai Lama knows intimately and at first-hand, I found them more persuasive than some of the other writing in the book about the interaction between science and Buddhism.

What I took from this book, and from the Pali Sutta discussed at the outset of this review, is that, in some instances, such as those captured by the poisoned arrow simile, spiritual questions are separate from those of science but that in other instances these questions interpenetrate. (That is, a person trying to understand him or herself needs to understand where science belongs in that particular endeavor) The results of scientific investigation, including specifically evolutionary theory, must be respected. But whatever science teaches, one must try to understand oneself and one's feelings, to understand suffering and grief, and to work towards a development of wisdom, compassion, and understanding. This is the message I took from the Dalai Lama's wonderful book.

Robin Friedman -

For all my introspection and soul-searching on the subject of how to integrate Western science into my philosophical views of the world, I wish that I had read this book years ago – it would have saved me a lot of hard thinking on my own. Ouch. As it turns out, the Dalai Lama has been on a decades-long campaign to import much of the Western science canon into the training of new Tibetan Buddhist monks. A large part of the book is spent discussing where science fails (reductionism/materialism) and how Buddhism can be used to bolster the scientific understanding of the natural world. The Dalai Lama’s arguments for incorporating science into formal Buddhist training are two-fold: In his view, Buddhism is empirically based. If the mind is put through a certain set of exercises, certain results can be expected. This empiricism meshes well with the construct of Western science. As a result, if something can be empirically proven, then that finding trumps any historical religious teachings, dogmas, or texts.

The second reason is that the Dalai Lama has great hope in meshing the spirituality of Buddhism with science. In particular, he is interested in applying the powers of science to the study of consciousness. Whereas science has historically taken on the role of a third person observer, the D.L. would like to produce a science of the first person where consciousness can be pulled out into the open and more fully described and appreciated. Fascinating stuff. -

This was a pretty nice exploration of the intersection of Science and Buddhist religion. The Dalai Lama came at this material from a very humble standpoint and makes that his religion could be greatly improved by approaching it from the standpoint of science (e.g. he admits that Buddhist cosmology is hopelessly archaic and should be replaced with current models).

Interestingly, he also points to some current research where Buddhist monastic disciplines have made contributions to the science of the brain: see PNAS vol. 101 no. 46 p 16369–16373 (2004). This was very nice work.

On the whole it was nice to see a religious leader that was not contemptuous of science and excited to work with scientists to expand our knowledge through sharing wisdom (old and new). -

เล่มนี้เป็นมุมมองของท่านทะไลลามะ ถึงวิทยาศาสตร์กับพุทธศาสนา

ท่านทะไลลามะสนทนาทั้งกับนักวิทยาศาสตร์สมัยใหม่และคุรุทางพุทธศาสนาหลายท่านจนตกผลึกมาถ่ายทอดผ่านหนังสือเล่มนี้

ท่านทะไลลามะยอมรับว่าวิทยาศาสตร์ก้าวหน้าไปมาก มีความรู้บางอย่างในคำสอนของพระพุทธเจ้าที่ต้องเปลี่ยนแปลงโดยเฉพาะด้านจักรวาลวิทยาและอะตอม

แต่ก็มีเรื่องหนึ่งที่ท่านยังมองว่าเป็นปริศนาคือเรื่อง ‘จิตวิญญาณ

สิ่งมีชีวิตกำเนิดอารมณ์ ความรู้สึกมาได้อย่างไร เราจะอธิบายอารมณ์ต่างๆ ค���ามเมตตาของเพื่อนมนุษย์ได้จากมุมมองวิทยาศาสตร์เพียงอย่างเดียวหรือ

ท่านเสนอว่าการเจริญสมาธิ ภาวนา อาจจะช่วยให้เราพัฒนา ส่งเสริมความเข้าใจเรื่องอารมณ์ให้กระจ่างยิ่งขึ้น

ท่านมีความกังวลที่วิทยาศาสตร์เริ่มมาเกี่ยวข้องกับการกำหนดพันธุกรรมของสิ่งมีชีวิต มีการตัดแต่งพันธุกรรม โคลนนิ่ง ตรวจเลือกกรรมพันธุ์เด็กก่อนเกิด

ซึ่งเป็นเรื่องละเอียดอ่อน เพราะไปยุ่งเกี่ยวกับการเนิดชีวิต ต้องเฝ้าระวังผลที่ตามมาอย่างใกล้ชิด

สุดท้ายที่ท่านเตือนให้ตระหนักคือ แม้วิทยาศาสตร์และเทคโนโลยีจะก้าวหน้าไปมาก แต่ขอให้เราใช้จิตวิญญาณ ความดีงามของมนุษย์นำทางสิ่งเหล่านี้ด้วย

เล่มนี้เล่าเรื่อย ๆ อ่านแล้วง่วง ๆ หน่อย แต่อ่านไม่ยาก -

With this book, the Dalai Lama shows that he is at once the most spiritual of persons, and the most practical. In

The Universe In A Single Atom, he shows one possible method for people living in the modern age of nuclear power, quantum physics and genetic engineering to combine the knowlege of science with the wisdom of spirituality. Just as Einstein thought that religion without science is blind and science without religion is lame, the Dalai Lama believes that "spirituality and science are different but complementary investigative approaches with the same greater goal, of seeking the truth."

The Universe In A Single Atom briefly tells the story of the Dalai Lama's education, spiritual and scientific, and explains his thoughts on how we can use both science and religion to make the world a better place. In doing so, the Dalai Lama examines the strengths and limitations of both. For instance, although he believes that science cannot answer such questions as the meaning of life or good and evil, and that there is "more to human existence and reality than science can ever give use access to," he although feels that "spirituality must be tempered by the insights and discoveries of science," and that a mind-set that ignores these "can lead to fundamentalism."

This book is full of common sense and wisdom. It can help anyone who has wrestled with the hard questions of the meaning of life to learn to live with the compassion and peace that comes from spirituality and the practical knowledge and wonder that springs from scientific understanding. -

I find it encouraging that the Dalai Lama is so open to new scientific ideas. Our world is changing at such a rapid rate. The ideas exploding into the field of physics are absolutely revolutionizing the way we view reality. It is interesting to hear some Buddhist commentary on the advancements of our age. I really enjoyed the last bit where he talked about some of the ethical consequences of bio genetic engineering, and was proud that he addressed this issue with such a strong stance for both plants and animals. The eastern way of thinking lends so well to enveloping and including all species of life in the great circle. I always find it concerning when spiritually minded individuals neglect or ignore their more real world thinking selves. Furthermore I think it is a good reminder of the importance of spirituality in the life of the academic. Learning to look at the world from all views brings wholeness and peace.

-

I've been a Hawking fan for years, but couldn't quite reconcile science with religion till I read this book. This was my introduction to the Dalai Lama, and I felt very comfortable first understanding his background and his curiosity, and, of course, his wisdom, as he explains, explores how empirical science and spirituality can coexist. In fact, one cannot exist without the other. I still have a lot of trouble with the Big Bang Theory, but am able to wrap my head around it a little better when you can add religion to the mix. Not mutually exclusive anymore. And I especially liked the Dalai Lama's humble way of presenting. The book felt friendly and not pedantic.

-

I definitely wanted this to be more in depth about the relationship between science and spirituality than just his interest in science, but I would still rate this 3.5 stars. He obviously is very wise and interested in learning, as well as devout in his faith, and believes that you can invest in both science and spirituality. The line that really resonated with me was fairly early on in the book, when he said "Just as we must avoid dogmatism in science, we must ensure that spirituality is free from the same limitations." The world is not science vs faith/spirituality, there is room for it all to intertwine.

-

Interessante para eu lembrar da minha ignorância, apesar de sistematicamente eu esquecer o quanto não sei nada em virtude de muita gente saber menos ainda.

-

As always, the Dalai Lama's synthesis of what appears to be the objective and the subjective, of science and spirituality is thought-provoking, uplifting and leads us to places where only someone with his extraordinary perspective is able to go. Brilliant and highly recommended!

-

I really wanted to like this book, but I decided to quit about 50 pages in. I skimmed the rest and decided that I had made the right decision. I found that the majority of this book was a bland and unfocused account of the Dalai Lama's friends who happened to be scientists over the years. It reads more like a biography than an intellectual exploration of the compatability (or lack thereof) between science and religion. I was hoping for a Jared Diamond-like narrative of facts and insights, but I got a bunch of fluff instead. Very disappointing--perhaps even more so than Art of Happiness (which I at least finished). I'm done with books by or about the Dalai Lama (although maybe something else on Buddhism might be worthwhile).

-

I liked the premise of the book - it's refreshing to see a major spiritual leader challenge religious folks to look at science. He proposes that in order to get the "whole picture" you've got to look at both sides - science and spirituality. But I slogged through the first few chapters, then just skipped right to the conclusion. Some of the sciency parts were over my head (and apparently over his head too). Perhaps I'm just not enough of a "thinker" (or wasn't in a thinking mood when I tried to read this). Just wasn't my cup o' tea!

-

I was just too confused with the concepts and details in this book. I really gave it an honest effort and read as much as I could. This is probably the first book in 8 years that I have started and not finished. I just didn't have it in me.

-

El cosmos budista es visto de otro punto de vista, según ellos primero fuimos seres etéreos, luego comimos materia, tuvimos que defecar y nos salieron órganos, finalmente la comida y el contexto nos hicieron diferentes y de ahí nacen las emociones: la envidia, el amor!! Està padrísimo!!!

-

Maybe my favorite read so far about how science and faith can work together. The Dalai Lama is rapidly becoming one of my favorite religious figures.

-

There is More To Science than Dreamt Of by the Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama clearly has a long-standing and genuine interest in science. He has access to the best minds in science, and hosts an annual conference on science. To his credit, he is humble about his limited understanding, and does not claim to have divine knowledge about what is true science. While he faithfully records what the scientists tell him in the book, it seems that he does not always understand them.

On page 12 he presents a concise summary of his philosophy of science, tied together with dubious logic. Unfortunately it ignores what the scientists told him. As it nicely sums up what is wrong in this otherwise worthwhile book, this review will examine it in detail, rather than evaluate the entire book.

“I have noticed that many people hold an assumption that the scientific view of the world should be the basis for all knowledge and all that is knowable. This is scientific materialism.”

The scientific view of the world is that it is comprehensible. We can explain what we observe by conjecturing rules, and testing to ensure they work. As our knowledge and investigative tools improve, we can observe new things that were unimaginable before. So science is the basis for all that is observable, remembering that there is always much more to be discovered. Ideas are an integral part of the reality that science investigates. Science itself is driven by our creativity, inventing new ideas to explain how the world works. “Scientific Materialism” is misleading if it means that scientific method is excluded from studying our mental processes or philosophy.

“This view upholds a belief in an objective world, independent of the contingency of its observers. It assumes that the data being analyzed within an experiment are independent of the preconceptions, perceptions, and experience of the scientist analyzing them.”

Science is indeed based on the concept of a single objective reality. The confusion here comes from the distinction between the reality of an object and our observation of it. Observation is certainly affected by the expectations and techniques of the scientist. Science is about overcoming these biases to arrive at an ever-improving approximation of the truth. The fact that we do not know exactly what is the truth does not mean there is no truth at all. This is a false dichotomy.

“Underlying this view is the assumption that, in the final analysis, matter, as it can be described by physics and as it is governed by the laws of physics, is all there is. Accordingly, this view would uphold that psychology can be reduced to biology, biology to chemistry, and chemistry to physics.”

Objective reality does not require or lead to reductionism. This misconception comes from the fact that an important part of science is about decomposing systems to investigate their parts. But science is also about unifying observations to create universal explanations. The alternative to reductionism is the view that when a certain level of complexity is reached, new laws emerge that cannot be described by the laws of the lower level. For example, your body is made up of cells. But even if we had perfect knowledge of how cells work, it would never describe you. Your life depends on your cells, you act through your cells, but it is impossible to understand you knowing only about your cells. Physics is therefore not sufficient to understand the world, even though everything that happens is ultimately based on physics. While there are no hard boundaries between physics, chemistry, biology and psychology, these sciences are separate disciplines because that is the only way to study the higher level rules that define them.

“My concern here is not to argue against this reductionist position, but to draw attention to a vitally important point: that these ideas do not constitute scientific knowledge; rather they represent a philosophical, in fact a metaphysical, position.”

This is indeed a vital point. For example, Newton’s laws of motion have been thoroughly tested and verified. But this established fact does not provide support for common metaphysical belief at the time in a clockwork universe, or for the physical assumption that time is the same everywhere. These notions were never experimentally verified, and have turned out to be false. We must always be careful to distinguish between verified scientific knowledge and the unverified theories and opinions of individual scientists.

When the Dalai Lama said on page 3 that Buddhism must align with “scientific analysis” he means verified knowledge, as opposed to unproven assumptions and metaphysics. As verified knowledge is rather limited in his domain of psychology, few of his fundamental beliefs are actually challenged. To his credit, he is willing to discard some of the myths that Buddhism inherited from Hinduism.

“The view that all aspects of reality can be reduced to matter and its various particles is, to my mind, as much a metaphysical position as the view that an organizing intelligence created and controls reality. The danger is that human beings may be reduced to nothing more than biological machines, the products of pure chance in the random combination of genes, with no purpose than the biological imperative of reproduction.”

A science that recognizes emergent properties knows that we are more than our cells, more than our genes, and more than our evolutionary heritage. Reductionism may be used as an excuse for nihilism, but it is curious how moral relativism, which is based on the rejection of the existence of objective reality, also leads to nihilism. Scientific method and Buddhism may both be seen as a middle way to the truth.

“According to the theory of emptiness, any belief in an objective reality grounded in the assumption of intrinsic, independent existence is untenable. All thing and events, whether material, mental, or even abstract concepts like time, are devoid of objective, independent existence. To possess such independent, intrinsic existence would imply that things and events are somehow complete unto themselves and are therefore entirely self-contained. This would mean that nothing has the capacity to interact with and exert influence on other phenomena.”

For a middle-way guy this is a hardline view. It is based on a false dichotomy playing on the word “independent”. Objects can exist independent of our observation of them without making them completely independent and isolated from everything.

Next we are told that belief in objective reality leads to “attachment, clinging, and the development of our numerous prejudices.”

The attachment issue is another false dichotomy. Some attachment is necessary to have any goals and get anything done (including meditation), while excessive attachment interferes with rational thinking. For example, the Dalai Lama seems to have an attachment to the theory of emptiness, not to mention to the independence of Tibet. The solution for attachment problems is not to wish the real world out of existence. This is like curing acne with suicide. As for prejudice, its very definition is to believe what you want to believe, rather than accept objective reality.

The denial of objective reality is not a problem for Buddhism because it also hands its students a pre-packaged purpose in life. For others, the logical conclusion is that if nothing objectively exists, you cannot really know anything. So believe anything you want, why care about anything?

The Dalai Lama does not support this kind moral relativism, if I understand this book at all. He seems to think first person introspection is ruled out by science. But if meditation actually leads to a tangible change, such as the state of mind or physiology of the meditator, or increased compassionate behavior, then this is also the realm of science. Why would the Dalia Lama invite scientists to study meditators if there was no reality to it? Again, an unnecessary restriction is being placed on science.

There is much to like about this book other than the philosophy of science it presents. Listen carefully to what the scientists tell him, as opposed to his conclusions, and remember that science can be broader than he gives it credit for. -

3/5

DNF

I have read a few books by the Dalai Lama XIV, that are based on the combining of spiritual practice and the science that drives the world. I have always loved his work, his thoughts, and his message. He truly is a blessed man.

I am keeping this review short because there are a few reasons on why I did not finish (DNF) this book.

1. Time - this was a library book that was sent to me from another library quite a ways away. Due to travel, time commitments, and finishing up 3 other books I was unable to get to this book until the last minute. Which is very unfortunate.

2. I did not like the actual science portion of the book. So, I picked up this book thinking how science and spirituality can be intertwined in today's technological empire. While I did get a feeling for this when the Dalai Lama would explain - at the end of each section - why the two are similar and not similar, I felt like the book was more on the basis of science. In some parts I felt like I was reading on science book on quantum phsyics, atom division, and so forth. Now this was explained at the beginning of the book on Lama's journey into science and that he would be delving into science very deeply, I just wish there was an emphasis on the actual Science into Spirituality and vice versa.

Now I am not saying I won't pick up this book in the future, because I would really like to read more into what he has to say on the subject. Currently, however, I must have not been in the mood to delve into the science portion at the level he has written. -

As an astrophysicist interested in Buddhism also currently reading a book in neuroscience, this book was right up my alley. I’m definitely glad I had that background, because this book really requires an understanding of the topics to appreciate the depth and philosophy of the relative discussions. I’d recommend three books to read beforehand:

1) Buddhist Ethics: A Very Short Introduction, by Damien Keown

2) Astrophysics for People in a Hurry, by Neil deGrasse Tyson [I may sub this for something more quantum focused]

3) Livewired, by David Eagleman

While the chapters on consciousness got a little long and lost for me in relating back to the connection with science, I thought the initial chapters on astrophysics and neuroscience, as well as the last chapter on the ethics of technology were particularly thought provoking. While there are some things I don’t agree with, they were still interesting ideas to think about. I was trying to imagine each person having a karmic Gaussian in time and that summing up to introduce a habitable world. Other things like the ancient Buddhist stories that include time dilation absolutely blew my mind (in a good way) though of how people can imagine this pre-relativistic physics.

A section of this book that I read in college is part of the reason why I became so interested in Buddhism and I really love the “Science and Religion can go together” argument. -

Por acá les coloco lo que me pareció más llamativo de este libro ;)

*El nombre del Dalai Lama es Tezin Gyatzo, nació en 1935 en el Tibet. Es el 14to Dalai Lama y es un guía espiritual del pueblo tibetano.

*Fue descubierto a los 4 años de edad e inició su formación. Se fue a vivir a la India por la invasión de China.

*Es un increíble estudioso de: filosofía, psicología, budismo, ciencias, física subatómica, cosmología, biología, neurociencias y del comportamiento humano.

*La teoría budista propone q la materia está formada por 8 sustancias subatómicas: tierra, aire, fuego, agua y forma, olor, gusto y tangibilidad.

*Los budistas creen en un universo sin comienzo, sino en la noción de q se encuentra en constante formación y destrucción.

*Budismo reconoce en los animales la consciencia con grado distinto a la humana. No reconoce en los animales algo parecido al alma.

*Según el budismo los humanos llegaron por nacimiento espontáneo.

*Karma significa acción!

*Conoció a Paul Ekman en el año 2000 y se apasionó por el estudio de las emociones básicas y cognitivas superiores.

*Conclusión: la ciencia y la epiritualidad comparten el mismo objetivo: mejorar la condición humana. -

Largely this is an autobiographical book about the Dalai Lama's personal journey with science and the fascination he has had for it since his childhood.

It does have some introductory material on how science works and some points of comparison between science and Buddhism.

Near the end it turned into a soft warning regarding the potential dangers of genetic modification.

There were many parts of the book I found quite inspirational especially some of his questions which led me on journeys to find my own answers. -

Với sứ mệnh cao cả. Ông được sinh ra để nói nên những sự thật và khai sáng cho những con người mất cân bằng cách tìm lại cân bằng cũng như kêu gọi mọi người hãy luôn sống với đạo đức. Suy nghĩ đạo đức, nói lời đạo đức và hành động đạo đức. Chúng ta luôn phải suy xét sâu xa trước khi thực hiện một hành động gì đó. Lời kêu gọi yêu thương ngôi nhà trái đất là bản chất của sự sống !!! Một cuốn sách đầy ý nghĩa và rất nhân văn.

-

I did not enjoy all of this, nor did I fully understand all of this (!) but the chapter on evolution and the chapter on genetics and ethics were fascinating.

“One empirical problem in Darwinism’s focus on the competitive survival of individuals (...) has consistently been how to explain altruism (...)” p. 112

What a fascinating thought.