| Title | : | Anna Karenina |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1593080271 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781593080273 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 803 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1878 |

| Awards | : | Premio literatura rusa en España (2012) |

Set against this tragic affair is the story of Konstantin Levin, a melancholy landowner whom Tolstoy based largely on himself. While Anna looks for happiness through love, Levin embarks on his own search for spiritual fulfillment through marriage, family, and hard work. Surrounding these two central plot threads are dozens of characters whom Tolstoy seamlessly weaves together, creating a breathtaking tapestry of nineteenth-century Russian society.

From its famous opening sentence — "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”—to its stunningly tragic conclusion, this enduring tale of marriage and adultery plumbs the very depths of the human soul.

Anna Karenina Reviews

-

As a daughter of a Russian literature teacher, it seems I have always known the story of Anna Karenina: the love, the affair, the train - the whole shebang. I must have ingested the knowledge with my mother's milk, as Russians would say.

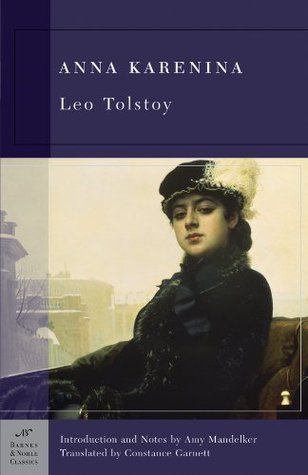

My grandpa had an old print of a painting hanging in his garage. A young beautiful mysterious woman sitting in a carriage in wintry Moscow and looking at the viewer through her heavy-lidded eyes with a stare that combines allure and deep sadness. "Who's that?" I asked my grandpa when I was five, and without missing a beat he answered, "Anna Karenina". Actually, it was "A Stranger" by Ivan Kramskoy (1883) - but for me it has always remained the mysterious and beautiful Anna Karenina, the femme fatale of Russian literature. (Imagine my childish glee when I saw this portrait used for the cover of this book in the edition I chose!)

Yet, "Anna Karenina" is a misleading title for this hefty tome as Anna's story is just the tip of an iceberg, as half of the story is devoted to Konstantin Levin, Tolstoy's alter ego (Count Leo's Russian name was Lev. Lev --> Levin), preoccupied with Russian peasantry and its relationship to land, as well as torn over faith and his lack of it, Levin whose story continues for chapters after Anna meets her train.

But Anna gives the book its name, and her plight spoke more to me than the philosophical dealings of an insecure and soul-searching Russian landowner, and so her story comes first. Sorry,LeoLevin.

Anna's chapters tell a story of a beautiful married woman who had a passionate affair with an officer and then somehow, in her quest for love, began a downward spiral fueled by jealousy and guilt and societal prejudices and stifling attitudes."But I'm glad you will see me as I am. The chief thing I shouldn't like would be for people to imagine I want to prove anything. I don't want to prove anything; I merely want to live, to do no one harm but myself. I have the right to do that, haven't I?"

On one hand, there's little new about the story of a forbidden, passionate, overwhelming affair resulting in societal scorn and the double standards towards a man and a woman involved in the same act. Few readers will be surprised that it is Anna who gets the blame for the affair, that it is Anna who is considered "fallen" and undesirable in the society, that it is Anna who is dependent on men in whichever relationship she is in because by societal norms of that time a woman was little else but a companion to her man. There is nothing new about the sad contrasts between the opportunities available to men and to women of that time - and the strong sense of superiority that men feel in this patriarchial world. No, there is nothing else in that, tragic as it may be."Anything, only not divorce!" answered Darya Alexandrovna.

"But what is anything?"

"No, it is awful! She will be no one's wife, she will be lost!"

No, where Lev Tolstoy excels is the portrayal of Anna's breakdown, Anna's downward spiral, the unraveling of her character under the ingrained guilt, crippling insecurity and the pressure the others - and she herself - place on her. Anna, a lovely, energetic, captivating woman, full of life and beauty, simply crumbles, sinks into despair, fueled by desperation and irrationality and misdirected passion."And he tried to think of her as she was when he met her the first time, at a railway station too, mysterious, exquisite, loving, seeking and giving happiness, and not cruelly revengeful as he remembered her on that last moment."

A calm and poised lady slowly and terrifyingly descends into fickle moods and depression and almost maniacal liveliness in between, tormented by her feeling of (imagined) abandonment and little self-worth and false passions which are little else but futile attempts to fill the void, the never-ending emptiness... This is what Tolstoy is a master at describing, and this is what was grabbing my heart and squeezing the joy out of it in anticipation of inevitable tragedy to come."In her eyes the whole of him, with all his habits, ideas, desires, with all his spiritual and physical temperament, was one thing—love for women, and that love, she felt, ought to be entirely concentrated on her alone. That love was less; consequently, as she reasoned, he must have transferred part of his love to other women or to another woman—and she was jealous. She was jealous not of any particular woman but of the decrease of his love. Not having got an object for her jealousy, she was on the lookout for it. At the slightest hint she transferred her jealousy from one object to another."

Yes, it's the little evils, the multitude of little faces of unhappiness that Count Tolstoy knows how to portray with such sense of reality that it's quite unsettling - be it the blind jealousy of Anna or Levin, be it the shameless cheating and spending of Stiva Oblonsky, be it the moral stuffiness and limits of Arkady Karenin, the parental neglects of both Karenins to their children, the lies, the little societal snipes, the disappointments, the failures, the pervasive selfishness... All of it is so unsettlingly well-captured on page that you do realize Tolstoy must have believed in the famous phrase that he penned for this book's opening line: "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

Tolstoy is excellent at showing that, despite what we tend to believe, getting what you wanted does not bring happiness."Vronsky, meanwhile, in spite of the complete realization of what he had so long desired, was not perfectly happy. He soon felt that the realization of his desires gave him no more than a grain of sand out of the mountain of happiness he had expected. It showed him the mistake men make in picturing to themselves happiness as the realization of their desires. "

And yet, just like in real life, there are no real villains, no real unsympathetic characters that cause obstacles for our heroes, the villains whom it feels good to hate. No, everyone, in addition to their pathetic little ugly traits also has redeeming qualities. Anna's husband, despite appearing as a monster to Anna after her passionate affair, still is initially willing to give her the freedom of the divorce that she needs. Stiva Oblonsky, repulsive in his carelessness and cheating, wins us over with his gregarious and genuinely friendly personality; Anna herself, despite her outbursts, is a devoted mother to her son (at least initially). Levin may appear to be monstrous in his jealousy, but the next moment he is so overwhelmingly in love that it's hard not to forgive him. And I love this greyness of each character, so lifelike and full.

And, of course, the politics - so easily forgettable by readers of this book that carries the name of the heroine of a passionate forbidden affair. The dreaded politics that bored me to tears when I was fifteen. And yet these are the politics and the questions that were so much on the mind of Count Tolstoy, famous to his compatriots for his love and devotion to peasants, that he devoted almost half of this thick tome to it, discussed through the thoughts of Konstantin Levin.

Levin, a landowner with a strong capacity for compassion, self-reflection and curiosity about Russian love for land, as well as a striking political apathy, is Tolstoy's avatar in trying to make sense of a puzzling Russian peasantry culture, which failed to be understood by many of his compatriots educated on the ideas and beliefs of industrialized Europe."He considered a revolution in economic conditions nonsense. But he always felt the injustice of his own abundance in comparison with the poverty of the peasants, and now he determined that so as to feel quite in the right, though he had worked hard and lived by no means luxuriously before, he would now work still harder, and would allow himself even less luxury."

I have to say - I understood his ideas more this time, but I could not really feel for the efforts of the devoted and kind landowner striving to understand the soul of Russian peasants. Maybe it's because I mentally kept fast-forwarding mere 50 years, to the Socialist Revolution of 1917 that would leave most definitely Levin and Kitty and their children dead, or less likely, in exile; the revolution which, as Tolstoy almost predicted, focused on the workers and despised the loved by Count Leo peasants, the revolution that despised the love for owning land and working it that Tolstoy felt was at the center of the Russian soul. But it is still incredibly interesting to think about and to analyze because even a century and a half later there's still enough truth and foresight in Tolstoy's musings, after all. Even if I disagree with so many of his views, they are still thought-provoking, no doubts about it."If he had been asked whether he liked or didn't like the peasants, Konstantin Levin would have been absolutely at a loss what to reply. He liked and did not like the peasants, just as he liked and did not like men in general. Of course, being a good-hearted man, he liked men rather than he disliked them, and so too with the peasants. But like or dislike "the people" as something apart he could not, not only because he lived with "the people," and all his interests were bound up with theirs, but also because he regarded himself as a part of "the people," did not see any special qualities or failings distinguishing himself and "the people," and could not contrast himself with them."

========================

It's a 3.5 star book for me. Why? Well, because of Tolstoy's prose, of course - because of its wordiness and repetitiveness.

Yes, Tolstoy is the undisputed king of creating page-long sentences (which I love, by the way - love that is owed in full to my literature-teacher mother admiring them and making me punctuate these never-ending sentences correctly for grammar exercises). But he is also a master of restating the obvious, repeating the same thought over and over and over again in the same sentence, in the same paragraph, until the reader is ready to cry for some respite. This, as well as Levin's at times obnoxious preachiness and the author's frequently very patriarchial views, was what made this book substantially less enjoyable than it could have been.

--------

By the way, there is an excellent 1967 Soviet film based on this book that captures the spirit of the book quite well (and, if you so like, has a handy function to turn on English subtitles): first part is

here, and the second part is

here. I highly recommend this film.

And even better version of this classic is the

British TV adaptation (2000) with stunning Helen McCrory as perfect Anna and lovely Paloma Baeza as perfect Kitty. -

***Spoiler alert. If you have read this book, please proceed. If you are never going to read this novel (be honest with yourself), then please proceed. If you may read this novel, but it may be decades in the future, then please proceed. Trust me, you are not going to remember, no matter how compelling a review I have written. If you need Tolstoy talking points for your next cocktail party or soiree with those literary, black wearing, pseudo intellectual friends of yours, then this review will come in handy. If they pin you to the board like a bug over some major plot twist, that will be because I have not shared any of those. If this happens, do not despair; refer them to my review. I’ll take the heat for you. If they don’t know who I am, then they are, frankly, not worth knowing. Exchange them for other more enlightened intellectual friends.***

“He soon felt that the fulfillment of his desires gave him only one grain of the mountain of happiness he had expected. This fulfillment showed him the eternal error men make in imagining that their happiness depends on the realization of their desires.”

Anna Arkadyevna married Alexei Alexandrovich Karenin, a man twenty years her senior. She dutifully produced a son for him and settled into a life of social events and extravagant clothes and enjoyed a freedom from financial worries. Maybe this life would have continued for her if she had never met Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky, but more than likely, her midlife crisis, her awareness of the passage of time, would have compelled her to seek something more.

”They say he’s a religious, moral, honest, intelligent man; but they don’t see what I’ve seen. They don’t know how he has been stifling my life for eight years, stifling everything that was alive in me, but he never once even thought that I was a living woman who needed love. They don’t know how he insulted me at every step and remained pleased with himself. Didn’t I try as hard as I could to find a justification for my life? Didn’t I try to love him… But the time has come, I’ve realized that I can no longer deceive myself, that I am alive, that I am not to blame if God has made me so that I must love and live. And what now? If he killed me, if he killed him, I could bear it all, I could forgive it all, but no, he….”

Her husband was enamored with her, but then so was everyone who met her, male or female. Maybe he was too contented with their life together and, therefore, took their relationship for granted. He was two decades older, so the passions of romance didn’t burn with as hot a flame. She wanted passion from him even if it was to murder her lover and herself. Even if it was something tragic, she wanted something to happen, something that would make her feel... something.

I couldn’t help thinking early on that the problem wasn’t with her husband, certainly nothing that a new lover could fix for very long. The same face was always going to greet her in the mirror. The same thoughts were always going to swim their way back to the surface. We can not mask the problems within ourselves by changing lovers. The mask will eventually slip, and all will be revealed.

Ugly can be very pretty.

Is there such a thing as being too beautiful? Can being so beautiful make someone cold, disdainful, and unable to really feel empathy or even connected to those around them? Her type of beauty is a shield that insulates her even as her insecurities swing the sword that stabs the hearts of those who despise her and those who love her.

”She was enchanting in her simple black dress, enchanting were her full arms with the bracelets on them, enchanting her firm neck with its string of pearls, enchanting her curly hair in disarray, enchanting the graceful, light movements of her small feet and hands, enchanting that beautiful face in its animation; but there was something terrible and cruel in her enchantment.”

My favorite character in this epic was Konstantin (Kostya) Dmitrich Levin. He was a well meaning, wealthy landowner who, unusually for the times, went out and worked the land himself. He got his hands dirty enough that one could actually call him a farmer. He was led to believe by his friends and even the Shcherbatsky family that their youngest daughter, Kitty, would be an affable match for him. Kitty’s older sister Dolly was married to Stepan (Stiva) Arkadyich Oblonsky, who was the brother to Anna Karenina.

Stiva was recently caught and forgiven for having a dalliance with a household staff, but no sooner was he out of that boiling water of that affair before he was having liaisons with a ballerina. This did lead me to believe that life would never be satisfying for either Stiva or his sister Anna because there was always going to be pretty butterflies to chase as the attractiveness of the one they had began to fade.

Before Vronsky became gobsmacked by Anna, he was leisurely chasing after Kitty and leading her on just long enough for Kitty to turn Levin’s marriage proposal down flat. That was like catching a molotok (hammer) right between the eyes as a serp (sickle) swept Kostya off his feet. Interestingly enough, later in the book Levin met Anna Karenina, after he has married Kitty (you’ll have to read the book to discover how this comes about), and he was captivated by Anna.

It was almost enough for me start chain smoking Turkish cigarettes or biting my nails down to the quick while I waited for the outcome. Substitute Anna for Jolene, and you’ll know what I was humming.

”She had unconsciously done everything she could to arouse a feeling of love for her in Levin, and though she knew that she had succeeded in it, as far as one could with regard to an honest, married man in one evening, and though she liked him very much, as soon as he left the room, she stopped thinking about him.”

If she was irritated with Vronsky, one day maybe she would just seduce Levin for entertainment... because she could.

I must say that I didn’t think much of Vronsky at the beginning of the novel, but as the plot progressed I started to sympathize with him. Tolstoy was brilliant at rounding out characters so our preconceived notions or the projections of ourselves that we place upon them are forced to be modified as we discover more about them.

Levin had his own problems. He had been reading the great philosophers, looking for answers. He found more questions than answers in religion. He abandoned every lifeboat he climbed into and swam for the next one. ”Without knowing what I am and why I’m here, it is impossible for me to live. And I cannot know that, therefore I cannot live.”

The problem that every reasonably intelligent person wrestles with is that no matter how successful we are, no matter how wonderful a life we build, or how well we take care of ourselves, we are going to die. It is irrefutable. Cemeteries don’t lie. Well, there is a lot of eternal lying down going on, but no duplicity. None of us are going to escape the reaper. No one is ascending on a cloud or going to the crossroads to make a deal with the Devil. We all have to come face to face with death, and we can’t take any of our bobbles, accolades, or power with us. So the question that Levin ended up asking himself, the Biggest question even beyond, why am I here? is:

Why do anything?

Without immortality, everything we attempt to do can seem futile. Some would make the case that we live on in our kids and grandkids. I say bugger to that. I want more time!

Well, there are ways to be immortal, and one of them is to write a masterpiece like Anna Karenina that will live forever.

By the end, I am ready to throttle Anna until her pretty eyes bug out of her head and her cheeks turn a vibrant pink, but at the same time, she seemed to be suffering from a host of mental disorders. She was so cut off from everyone and so disdainful of everyone. ”It was impossible not to hate such pathetically ugly people.” The “friends” she had had been ostracized from her by her own actions. I had to believe her loathing of people was a projection of how she felt about herself. She needed some time on Carl Jung’s couch, but he was a wee tot when this book was published. She needed to find some satisfaction in the ordinary and quit believing that a change in geography or in lovers was ever going to fix what was wrong with herself.

She had such a destructive personality. One man tried to kill himself from her actions and another contemplated the act. She was maliciously vengeful when someone didn’t do something she wanted them to do; and yet, I couldn’t quite condemn her completely. Her feelings of being stifled were perfectly natural. We all feel that way at points in our lives. We feel trapped by the circumstances of our life. Her attempt to break free in the 1870s in Russian society was brave/foolish. She sacrificed everything to chase a dream.

The dream ate her.

This book is a masterpiece, not just a Russian masterpiece but a true gift to the world of literature.

If you wish to see more of my most recent book and movie reviews visit

http://www.jeffreykeeten.com

I also have a Facebook blogger page at:

https://www.facebook.com/JeffreyKeeten -

welcome to...ANNA DECEMBERENINA!

it's the start of the month (kinda). i've attempted a (reprehensible) pun on a book title (to everyone's chagrin). there is a notoriously long classic on my currently reading (ill-advisedly).

you know what that means.

IT'S

PROJECT LONG CLASSIC TIME, the fan favorite in which i read a very long book divided up into little bits over the course of the month, and usually i drag

elle along with me except this month i'm planning something truly nightmarish so i'm starting while she's asleep as an act of terror / peer pressure.

let's do this.

DAY 1: PAGES 1-25

my tbr review of this was "sometimes i like to pretend i'm capable of reading thousand-page books. just for fun," and in this case that pretending includes starting 2 days early and doubling up eventually so that i can read in 25 page chunks.

i'm cool like that.

damn! that opening line! we are off to the races.

DAY 2: PAGES 26-75

didn't even intend to make today my bonus day but this is just so readable. why didn't anyone tell me the 900 page classic from 150 years ago is unputdownable??

i fear i may adore all of these characters.

DAY 3: 76-100

in a state of bliss right now in which i look forward to reading this every day but am relishing it so much that dividing it into sections works perfectly.

DAY 4: 101-125

literally any book is doable in teeny chunks like this. i had negative free time (and a negative interest) today but boom. easy money.

DAY 5: 126-150

the descriptions of emotions in this...sheesh. excellence.

DAY 6: 151-175

and here we have the farming sections i've heard so much about...

in truth if they're like this every time i can handle it. i like poetic descriptions of the descent of springtime as much as the next annoying girl.

DAY 7: 176-200

i am absolutely indulging in vronsky's downfall here. finding pleasure in his every misfortune. his sadness and disappointment spark joy for me.

hate that guy.

DAY 8: 201-225

well jesus anna! we're only at the 25% mark, we can't act like this already!

DAY 10: 226-250

i missed a day. i'm a nightmare person.

now i have to see how many pages i can manage in, generously, 20 minutes.

perhaps unsurprisingly it took 25 and i'm not caught up.

DAY 11: PAGES 251-275

something fun that the universe and i are doing is that we've set up the last three weeks of the year so that i don't only have to finish 24 books, complete two projects, and remain active on seemingly 100 accounts, but i also have the busiest work week(s) i have had in (without exaggeration) 2 years.

without the depressive episode that made the last time so fun.

anyway i may never catch up on this.

DAY 13: PAGES 276-300

guess who's behind. behind again. emma's behind. except she never caught up in the first place so now she's just...50 pages behind instead of 25.

or i guess 75 since i haven't actually read any yet today.

okay NOW 50. why is this book so good??

DAY 14: PAGES 301-350

well, well, well. look who decided to catch up.

biiiiig farming chapters.

DAY 15: PAGES 351-375

part four alert. we pray for mercy from agricultural labor bureaucracy content.

and our prayers are heard <3

DAY 16: PAGES 376-400

KITTY AND LEVIN!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

wow i am so invested in this. even dozens of pages about farming and politics can't divest me. i am in it.

DAY 17: PAGES 401-425

way, way, way too much is happening. it's the halfway point, people! this is no time for climaxes OR happily ever afters, let alone both! we have 400+ pages to cover!

DAY 18: PAGES 426-450

i am uncomfortable with how high stakes everything is. THERE IS SO MUCH LEFT. WHEN I HEFT THIS UNWIELDY VOLUME I AM ONLY AT THE HALFWAY POINT EVEN STILL. I THINK. EVEN THOUGH I'VE BEEN SAYING THAT FOR SEEMINGLY DAYS.

DAY 19: 451-475

honestly i care less about the Christian Art than the farming. sheesh.

DAY 20: 476-500

it's the circleeee of lifeee...

DAY 21: 501-525

what a moral quandary we find ourselves in!

DAY 22: 526-550

okay phew, i'm back on board with being obsessed with anna. it makes me uncomfortable to not like a female character who is constantly committing moral wrongs...feels unnatural.

part 5 done!

DAY 23: 551-575

i'm internally titling this one twenty-five page chunk number 23: the tangled webs we weave. get it together, folks! it's like a sally rooney novel in here.

DAY 24: 576-600

this too realistically conveyed the feeling of being clinically annoyed by a friend of a friend. i feel irritable now.

DAY 28: 601-650

it's the most wonderful time of the year...

read: it's actually december 26, meaning we have actually skipped right to day 28, and i am extremely behind just in time for the end of the year to be right around the corner.

but i'm also behind on my

other project, and i'm also behind on my actual literal reading challenge, so we're just going to ignore that for today. no time for worrying, only time for reading.

actually read 50 pages anyway because i am perfect and infallible.

DAY 31: PAGES 651-700

being very brave and reading 50 pages again and also pretending anna isn't on my damn nerves. GIRL STAND UP.

we find ourselves heading into part 7.

never mind. it's not hard to not be bugged by anna. she's the sh*t.

DAY 32: PAGES 701-750

anna is so evil and kitty is so perfect. i love them both.

DAY 33: PAGES 751-817

it appears it is time. hello and welcome to the last day of the anna karenina project.

oh man.

OVERALL

not only was i intimidated by this book's length, i was sure i'd find it unconquerable. even as i started it and found it a pleasure, i was waiting for the other shoe to drop. it never did! i enjoyed this every day, through farming and politics and religion and art.

readable and sweeping, stunning in its writing and its carrying across effortlessly of both the minutiae and the most important topics of life. it's insane how applicable, how of the moment this book is now, across languages and centuries.

read it! i can't believe how long i put it off.

rating: 4.5 -

In the beginning, reading Anna Karenin can feel a little like visiting Paris for the first time. You’ve heard a lot about the place before you go. Much of what you see from the bus you recognize from pictures and movies and books. You can’t help but think of the great writers and artists who have been here before you. You expect to like it. You want to like it. But you don’t want to feel like you have to like it. You worry a little that you won’t. But after a few days, you settle in, and you feel the immensity of the place opening up all around you. You keep having this experience of turning a corner and finding something beautiful that you hadn’t been told to expect or catching sight of something familiar from a surprising angle. You start to trust the abundance of the place, and your anxieties that someone else will have eaten everything up before your arrival relax. (Maybe that simile reveals more about me than I’d like.)

My favorite discovery was the three or four chapters (out of the book’s 239) devoted to, of all things, scythe mowing—chapters that become a celebratory meditation on physical labor. When I read those chapters, I felt temporarily cured of the need to have something “happen” and became as absorbed in the reading as the mowers are absorbed in their work. Of course, the book is about Anna and Vronsky and Levin and Kitty and Dolly and poor, stupid Stepan Arkadyich. It��s about their love and courtship and friendship and pride and shame and jealousy and betrayal and forgiveness and about the instable variety of happiness and unhappiness. But it’s also about mowing the grass and arguing politics and hunting and working as a bureaucrat and raising children and dealing politely with tedious company. To put it more accurately, it’s about the way that the human mind—or, as Tolstoy sometimes says, the human soul—engages each of these experiences and tries to understand itself, the world around it, and the other souls that inhabit that world. This book is not afraid to take up any part of human life because it believes that human beings are infinitely interesting and infinitely worthy of compassion. And, what I found stirring, the book’s fearlessness extends to matters of religion. Tolstoy takes his characters seriously enough to acknowledge that they have spiritual lives that are as nuanced and mysterious as their intellectual lives and their romantic lives. I knew to expect this dimension of the book, but I could not have known how encouraging it would be to dwell in it for so long.

In the end, this is a book about life, written by a man who is profoundly in love with life. Reading it makes me want to live. -

This is a book that I was actually dreading reading for quite some time. It was on a list of books that I'd been working my way through and, after seeing the size of it and the fact that 'War And Peace' was voted #1 book to avoid reading, I was reluctant to ever get started. But am I glad that I did.

This is a surprisingly fast-moving, interesting and easy to read novel. The last of which I'd of never believed could be true before reading it, but you find yourself instantly engrossed in this kind of Russian soap opera, filled with weird and intriguing characters. The most notable theme is the way society overlooked mens' affairs but frowned on womens', this immediately created a bond between myself and Anna, who is an extremely likeable character.

I thought it had an amazing balance of important meaning and light-heartedness. Let's just say, it's given me some courage to maybe one day try out the dreaded 'War And Peace'. -

Blog |

Facebook |

Twitter |

Instagram |

Pinterest -

ساجعلكم تتعاطفون مع أسوأ نموذج بشري

بل ستبكون من أجلها ايضا..هتف تولستوى

لتولد رواية أشبه بالدولاب المزدحم المكدس بالاغراض..ما ان تفتحه فجأة حتى تقفز شخصيات كثيرة و غنية في وجهك..بجانب الثلاثي الشهير انا و أليكسي و اليكسي.. يوجد اربع أبطال اخرين..الفصول تبدا بالخيانة و لكنها خيانة رجل!!ثم تلطمك الاحداث الحافلة بالنقد الاجتماعي و السياسي..و الاستطرادات الذكية

تحدى تولستوى أصدقاؤه عندما سالهم عن البطلة الأسوأ👀 و الاقل تعاطفا ..فاكدوا انها المرأة الخائنة بالطبع ..فبدأ ملحمته الكبرى الثانية. .التي حملت بين طياتها بذرة الخلود

كل العائلات السعيدة تتشابه..و لكن كل عائلة تعيسة ..هي تعيسة بطريقتها الخاصة

تلك الافتتاحية الصادقة ستظل الأكثر شهرة على الاطلاق

تمت كتابة انا كارنينا على 8اجزاء في عامين..تاخرت البطلة عن الظهور لاكثر من 150 صفحة 😨

بدأ ظهورها في القطار و انتهت قصتها معه ايضا في رمزية بارعة

هنا لا توجد اقتباسات لا تنسى ..و لا احداث حافلة ..بل حياة حقيقية بمشاغلها و اعرافها.. برتباتها و مللها..مليئة بالمشاعر و الأراء ..دموع..و ندم..صدرت بعد سنوات من مدام بوفاري و لكن شتان..شتان..قد يكون اسلوب فلوبير أكثر عبقرية و لكن ستتعاطف مع "انا " و تلعن بوفاري

تولستوي حكم اخلاقيا على انا. .مع انه منحها اسبابا عدة للسقوط..الا انه لم يتركها تستمريء الخيانة و هي متنعمة بخير زوجها..بل سرعان ما رحلت لتخسر كل شيء..لتعي بطلتنا جيدا كيف يتسامح المجتمع مع الرجل..بينما هي..هي ؟؟

الرواية تصلح كدرس مضاد للرومانسية..قاسيا لأبعد الحدود

قراءة الف صفحة قرار ليس بهّين ..قدتتعاطف مع الأبطال او تكرههم

و لكن تأكد انك ستمنحهم فرصة للحياة في ذاكرتك للابد -

WARNING: This is not a strict book review, but rather a meta-review of what reading this book led to in my life. Please avoid reading this if you're looking for an in depth analysis of

Anna Karenina. Thanks. I should also mention that there is a big spoiler in here, in case you've remained untouched by cultural osmosis, but you should read my review anyway to save yourself the trouble.

I grew up believing, like most of us, that burning books was something Nazis did (though, of course, burning Disco records at Shea stadium was perfectly fine). I believed that burning books was only a couple of steps down from burning people in ovens, or that it was, at least, a step towards holocaust.

If I heard the words "burning books" or "book burning," I saw Gestapo, SS and SA marching around a mountainous bonfire of books in a menacingly lit square. It's a scary image: an image of censorship, of fear mongering, of mind control -- an image of evil. So I never imagined that I would become a book burner.

That all changed the day Anna Karenina, that insufferable, whiny, pathetic, pain in the ass, finally jumped off the platform and killed herself.

That summer I was performing in Shakespeare in the Mountains, and I knew I'd have plenty of down time, so it was a perfect summer to read another 1,000 page+ novel. I'd read

Count of Monte Cristo one summer when I was working day camps,

Les Miserable one summer when I was working at a residential camp, and

Shogun in one of my final summers of zero responsibility. A summer shifting back and forth between Marc Antony in

Julius Caesar and Pinch, Antonio and the Nun (which I played with great gusto, impersonating Terry Jones in drag) in

Comedy of Errors, or sitting at a pub in the mountains while I waited for the matinee to give way to the evening show, seemed an ideal time to blaze through a big meaty classic. I narrowed the field to two by

Tolstoy:

War and Peace and

Anna Karenina. I chose the latter and was very quickly sorry I did.

I have never met such an unlikable bunch of bunsholes in my life (m'kay...I admit it...I am applying Mr. Mackey's lesson. You should see how much money I've put in the vulgarity jar this past week). Seriously. I loathed them all and couldn't give a damn about their problems. By the end of the first part I was longing for Anna to kill herself (I'd known the ending since I was a kid, and if you didn't and I spoiled it for you, sorry. But how could you not know before now?). I wanted horrible things to happen to everyone. I wanted Vronsky to die when his horse breaks its back. I wanted everyone else to die of consumption like Nikolai. And then I started thinking of how much fun it would be to rewrite this book with a mad Stalin cleansing the whole bunch of them and sending them to a Gulag (in fact, this book is the ultimate excuse for the October Revolution (though I am not comparing Stalinism to Bolshevism). If I'd lived as a serf amongst this pack of idiots I'd have supported the Bolshies without a second thought).

I found the book excruciating, but I was locked in my life long need to finish ANY book I started. It was a compulsion I had never been able to break, and I had the time for it that summer. I spent three months in the presence of powerful and/or fun

Shakespeare plays and contrasted those with a soul suckingly unenjoyable

Tolstoy novel, and then I couldn't escape because of my own head. I told myself many things to get through it all: "I am missing the point," "Something's missing in translation," "I'm in the wrong head space," "I shouldn't have read it while I was living and breathing Shakespeare," "It will get better."

It never did. Not for me. I hated every m'kaying page. Then near the end of the summer, while I was sitting in the tent a couple of hours from the matinee (I remember it was Comedy of Errors because I was there early to set up the puppet theatre), I finally had the momentary joy of Anna's suicide. Ecstasy! She was gone. And I was almost free. But then I wasn't free because I still had the final part of the novel to read, and I needed to get ready for the show, then after the show I was heading out to claim a campsite for an overnight before coming back for an evening show of Caesar. I was worried I wouldn't have time to finish that day, but I read pages whenever I found a free moment and it was looking good.

Come twilight, I was through with the shows and back at camp with Erika and my little cousin Shaina. The fire was innocently crackling, Erika was making hot dogs with Shaina, so I retreated to the tent and pushed through the rest of the book. When it was over, I emerged full of anger and bile and tossed the book onto the picnic table with disgust. I sat in front of the fire, eating my hot dogs and drinking beer, and that's when the fire stopped being innocent. I knew I needed to burn this book.

I couldn't do it at first. I had to talk myself into it, and I don't think I could have done it at all if Erika hadn't supported the decision. She'd lived through all of my complaining, though, and knew how much I hated the book (and I am pretty sure she hated listening to my complaints almost as much). So I looked at the book and the fire. I ate marshmallows and spewed my disdain. I sang Beatles songs, then went back to my rage, and finally I just stood up and said "M'kay it!"

I tossed it into the flames and watched that brick of a book slowly twist and char and begin to float into the night sky. The fire around the book blazed high for a good ten minutes, the first minute of which was colored by the inks of the cover, then it tumbled off its prop log and into the heart of the coals, disappearing forever. I cheered and danced and exorcised that book from my system. I felt better. I was cleansed of my communion with those whiny Russians. And I vowed in that moment to never again allow myself to get locked into a book I couldn't stand; it's still hard, but I have put a few aside.

Since the burning of

Anna Karenina there have been a few books that have followed it into the flames. Some because I loved them and wanted to give them an appropriate pyre, some because I loathed them and wanted to condemn them to the fire. I don't see Nazis marching around the flames anymore either. I see a clear mountain night, I taste bad wine and hot dogs, I hear wind forty feet up in the tops of the trees, I smell the chemical pong of toxic ink, and I feel the relief of never having to see

Anna Karenina on my bookshelf again.

Whew. I feel much better now. -

As part of my reading challenge this year, I wanted to read at least one or two classics, and Anna Karenina was high on my list. It's considered by many to be one of the best novels ever written, and I've never read any Tolstoy. So even though it's a monster at more than 800 pages, I decided it's time I conquered it.

The story starts out so strong, with what seems to be an insightful treatise into the family and romantic life of several characters, including title character Anna. The domestic strife, misunderstandings, affairs, and life in general of the Russian elite, when boiled down to its essentials, are not so different from what occupy people's attentions today. I found the initial chapters to be interesting, and was drawn towards the circle of people who would make up the main cast of the book.

Then as the story progressed, things started to reach their natural conclusions, until about halfway through the book. At that point, I wish Tolstoy would have stopped because I found the second half to be more or less unnecessary. Everything had been resolved by then. But Tolstoy continued, and for me, the story just fell apart after that.

The main characters, in particular Anna, having gotten what they wished for, started acting loony, for lack of a better word. The more their wishes came true, the unhappier they became. A good portion of the second half was devoted to Anna lamenting how her partner does not love her. Every time he goes somewhere, she would pounce on him as soon as he comes home, saying crazy things about how he must be thinking of other women and no longer of her. He would reassure her constantly of his love and unending devotion. She wouldn't listen, so when he inevitably would get frustrated, she took that as confirmation that he doesn't love her. She would leave messages for him not to bother her, and when he doesn't, she would take that as a sign that she is right. This went on for like 200 pages. I wanted to stab myself every time Anna showed up in a scene. It's hard to tolerate a book when you dislike the main character that much.

I'm also a little uncomfortable that Tolstoy seems to portray women in his story as weak and mentally unstable, while the men are portrayed as high-thinking orators. The women would fly into tears and rages at the drop of a hat, stirring up domestic trouble while their men are out doing their jobs or hanging out with their buddies. The women also blushed uncontrollably when talking to any man who isn't their husband. Maybe this is just the way it was during Tolstoy's time and this book would have been seen as progressive, but as a modern woman reading it now, it makes me cringe so hard.

Tolstoy also seems to have treated this book as a vehicle to get out whatever he wanted to say on a variety of topics, including farming techniques, local governments and elections, the meaning of life, religion, snipe shooting, duty and rights of citizens, etc. This book is full of philosophical musings on these topics and more. I don't mind when authors want to present interesting and tangential thoughts, but Tolstoy did it constantly and without filter. His ramblings would go on for many chapters, and were so unedited that it's essentially a stream of consciousness. I'm sure there are some good points in there, but it's so buried under pages of unreadable and irrelevant prattle that I couldn't find them. While these technical and philosophical ruminations are all throughout the book, they were much worse in the second half, taking up a significant portion of it.

Reading this 800+ page tome has been an odyssey. I didn't find any of the characters to be particularly likable or charming. They were all rather silly, unstable, or full of themselves. To me, this is far from one of the best books I've ever read, though it's possible that back then, when there wasn't much to read or do for fun, this would have fulfilled that role. Now I can say I have read Anna Karenina, but that's about as much as I got out of it. -

People are going to have to remember that this is the part of the review that is entirely of my own opinion and what I thought of the book, because what follows isn't entirely positive, but I hope it doesn't throw you off the book entirely and you still give it a chance. Now... my thoughts:

I picked up this book upon the advice of Oprah (and her book club) and my friend Kit. They owe me hardcore now. As does Mr. Tolstoy. This book was an extremely long read, not because of it's size and length necessarily, but because of it's content. More often than not I found myself suddenly third a way down the page after my mind wandered off to other thoughts but I kept on reading... am I the only one with the ability to do that? You know, totally zoning out but continuing to read? The subject I passed over though was so thoroughly boring that I didn't bother going back to re-read it... and it didn't affect my understanding of future events taking place later on in the book.

Leo Tolstoy really enjoys tangents. Constantly drifting away from the point of the book to go off on three page rants on farming methods, political policies and elections, or philosophical discussion on God. Even the dialogue drifted off in that sort of manner. Tolstoy constantly made detail of trifling matters, while important subjects that added to what little plot line this story had were just passed over. Here is a small passage that is a wonderful example of what constantly takes place throughout the book:

"Kostia, look out! There's a bee! Won't he sting?" cried Dolly, defending herself from a wasp.

"That's not a bee; that's a wasp!" said Levin.

"Come, now! Give us your theory," demanded Katavasof, evidently provoking Levin to a discussion. "Why shouldn't private persons have that right?"

No mention of the wasp is made again. Just a small example of how Tolstoy focuses much more on philosophical thought, and thought in general, more than any sort of action that will progress the story further. That's part of the reason the story took so long to get through.

The editing and translation of the version I got also wasn't very good. Kit reckons that that's part of the reason I didn't enjoy it as much, and I am apt to agree with her. If you do decide to read this book, your better choice is to go with the Oprah's Book Club edition of Anna Karenina.

The characters weren't too great either and I felt only slightly sympathetic for them at certain moments. The women most often were whiny and weak while the men seemed cruel and judgemental more often than not. Even Anna, who was supposedly strong-willed and intelligent would go off on these irrational rants. The women were constantly jealous and the men were always suspicious.

There's not much else to say that I haven't already said. There were only certain spots in the book which I enjoyed in the littlest, and even then I can't remember them. All in all I did not enjoy this book, and it earned the names Anna Crapenina and Anna Kareniblah.

But remember this is just one girl's opinion, if it sounded like a book you might enjoy I highly advise going out to read it. Just try and get the Oprah edition. -

(Book 840 From 1001 Books) - Анна Каренина = Anna Karenina = Anna Karenin, Leo Tolstoy

Anna Karenina is a novel by the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, published in serial installments from 1873 to 1877 in the periodical The Russian Messenger.

A complex novel in eight parts, with more than a dozen major characters, it is spread over more than 800 pages (depending on the translation and publisher), typically contained in two volumes.

It deals with themes of betrayal, faith, family, marriage, Imperial Russian society, desire, and rural vs. city life.

The plot centers on an extramarital affair between Anna and dashing cavalry officer Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky that scandalizes the social circles of Saint Petersburg and forces the young lovers to flee to Italy in a search for happiness. After they return to Russia, their lives further unravel.

Characters: Princess Ekaterina "Kitty" Aleksandrovna Shcherbatskaya, Anna Arkadyevna Karenina, Count Aleksei Kirillovich Vronsky, Konstantin "Kostya" Dmitrievitch Levin, Prince Stepan "Stiva" Arkadyevitch Oblonsky.

عنوان چاپ شده در ایران: «آنا کارنینا» نویسنده: لئو ن تولستوی (نیلوفر) ادبیات روسیه؛ انتشاراتیها: (ساحل، نیلوفر، کلبه سفید، سمیر، گوتنبرگ)؛ تاریخ نخستین خوانش روز بیست و چهارم ماه فوریه سال 1985میلادی

عنوان: آنا کارنینا؛ نویسنده: لئو ن تولستوی؛ مترجم: محمدعلی شیرازی؛ تهران، ساحل، 1348، در 346ص؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان روسیه - سده 19م

عنوان: آنا کارنینا؛ نویسنده: تولستوی؛ مترجم: سروش حبیبی؛ تهران، نیلوفر، 1378، در 1024ص، در 2جلد، شابک 9644481127؛

عنوان: آنا کارنینا؛ نویسنده: تولستوی؛ مترجم: فرناز آشتیانی؛ تهران، کلبه سفید، 1383، در 496ص، شابک 9649360166؛

عنوان: آنا کارنینا؛ نویسنده: تولستوی؛ مترجم: قازار سیمونیان؛ تهران، سمیر، گوتنبرگ، چاپ چهارم 1388، در 864ص، شابک 9789646552364؛

بیش از نیمی از داستان، درباره ی «آنا کارنینا»ست؛ باقی درباره ی فردی به نام «لوین» است، البته که این دو شخصیت، در داستان رابطه ی دورادوری با هم دارند؛ به عبارتی، «آنا کارِنینا»، خواهرِ دوستِ «لوین» است؛ در طولِ داستان، این دو شخصیت، تنها یکبار، و آنهم در اواخرِ داستان، با هم رودررو میشوند؛ پس، رمان تنها به زندگی «آنا کارِنینا» اشاره ندارد، و در آن، به زندگی و افکار شخصیتهای دیگرِ داستان نیز، توجه شده است؛ «آنا»، نام این زن است، و «کارِنین»، نام همسرِ ایشانست، و او به مناسبت نام شوهرش، «آنا کارِنینا (مؤنثِ «کارِنین»)» نامیده میشود؛ «تولستوی» در نگارش این داستان، کوشیده، برخی افکار خود را، در قالب دیالوگهای متن، به خوانشگر بباوراند، تا او را به اندیشیدن وادارد؛

در قسمتهایی از داستان، «تولستوی»، درباره ی شیوه های بهبود کشاورزی، یا آموزش نیز، سخن گفته؛ که نشان دهنده ی اطلاعات ژرف نویسنده، در این زمینه نیز هست؛ البته بیان این اطلاعات و افکار، گاهی باعت شده، داستان از موضوع اصلی دور، و برای خوانشگر خسته کننده شود؛ داستان از آنجا آغاز میشود که زن و شوهری به نامهای: «استپان آرکادیچ»، و «داریا الکساندرونا»؛ با هم اختلافی خانوادگی دارند.؛ «آنا کارِنینا»، خواهر «استپان آرکادیچ» است، و از «سن پترزبورگ» به خانه ی برادرش ــ که در «مسکو» است ــ میآید؛ و اختلاف زن و شوهر را به سامان میکند؛ حضور آنا در «مسکو»، باعث به وجود آمدن ماجراهای اصلیِ داستان میشود...؛

فضای اشرافیِ آن روزگار، بر داستان حاکم است؛ زمانیکه پرنسها و کنتها، دارای مقامی والا در جامعه بودند؛ در کل، این داستان، روندی نرم، و دلنشین دارد؛ و به باور دیگران، فضای خشک داستان «جنگ و صلح»، بر «آنا کارنینا» حاکم نیست؛ این داستان، که درونمایه ای عاشقانه ـ اجتماعی دارد، شاید پس از «جنگ و صلح»، بزرگترین اثر «تولستوی» بزرگ، به شمار است، تولستوی خود این اثر خویش را برتر میشمارند

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 02/06/1399هجری خورشیدی؛ 06/05/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

goodness me, russians are dramatic. and i wouldnt have it any other way.

tolstoy is a master character creator. and although he is very skilled at conveying pre-revolution life and society, i have found much more enjoyment in his characters (shoutout to my boy, levin) than the plot. that being said, there is a certain complexity in tolstoys method of storytelling. there isnt a clear resolution in sight for most of the novel, so it left me eager to see what the characters would do and how the story would play out.

also, on a side note, i am of the strong opinion that leo was on one when he chose the title for this.

↠ 4.5 stars -

I am happy to have discovered this little marvel of deciphering nature and human passions, not in my 'Russian classics' around 20 years! At the time, I found significant serenity there, especially with Dostoievski. Today, regarding the question of maturity or only of work, I see something quite different: a magnificent painting, both beautiful and tragic, of the human condition, with a lot of ironies and even more finesse in the analysis psychological. In short, a masterpiece.

As the title suggests, we follow the story of Anna Karenina, the wife of a high Russian dignitary; she is beautiful, healthy, joyful, and radiant until she meets passion, its complications, and its compromises. But, as the title does not indicate, there is also a whole gallery of portraits: her lover Vronsky, sometimes enthusiastic seducer, a sometimes responsible and wise man; her husband Karenina, all confided in his respectability but touched by his sufferings and his dignity; Levine, accurate literary double of Tolstoi according to the notice, the tortured, the pragmatist and the lover; Kitty, the simple, sweet and good woman, after having been a little brainless; the good-natured but well-intentioned parasite Oblonski; and so many others which will take us to the mundane and somewhat idle salons of Saint Petersburg, the revolutionary circles, the district assemblies or deep into the Russian countryside.

What is extraordinary (or terrible, depending on which point of view you take) is that you find yourself in the characters and the situations. I am not a 19th-century Russian aristocrat engaged in a passionate affair. Yet I understand her, especially in her paradoxes, constant doubts, inability to stop the spiral of arguments, her interpretations distorted by anxiety, his exaltation, and his absolute love. So much more than the adulterous woman, it is the incarnation of the woman in love: if she had lived today, with the possibilities of divorce and professional activity for women, could she have loved Vronsky? And quietly? I'm not sure. And she will remain a tragic heroine with whom I especially would not like to identify!

Failing to look like the heroine, I am thrilled by my reading, which explains this review is probably a little confusing. -

What is the most important thing about Anna Karenina? Is it the first line, "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way"? This sounds so true but it isn't really.

Is it that Anna experiences much more intolerance for her unfaithfulness and leaving her husband than does her brother who screws around like a dog? Is it Konstantin Levin's attempts to marry into the aristocracy and his problem with religion? Or is the entire story just Tolstoy's way of seducing the reader into reading the political nub of the story, the feudalism that was at the heart of all politics, morality and social position.

I enjoyed the book when I read it, but I have to say I skimmed over a lot of the politics and did wonder which in Tolstoy's heart is the story he wanted to tell, love stories or political ones?

How I came to read Anna Karenina, appendicitis and an air hostess ending with a rotten tomato.

I will never forget Anna Karenina, apart from Tolstoy's political rants and plight of the peasants etc, the book was a pure gold, convoluted love affair. It was like all the best books are, total immersion in another world populated by real people whose lives outside of those described you could easily imagine, not just "well-drawn characters". Austen, Bronte, Mrs. Gaskell and Zola were just as good, all of them worlds I lived in when I read their books.

Review 1/2020 Rewritten 15th Jan 2020 to include more about the book. -

"Leo Tolstoy would meet hatred expressed in violence by love expressed in self-suffering."

—Mahatma Gandhi

Through reading this praiseworthy classic, I have been forced to recalibrate my previously unreliable view of this celebrated author.

You see, I was force-fed Tolstoy at college (his writing, not his flesh, silly! Mine wasn't a college for cannibals!) and at the time only carried War and Peace under one arm so I might appear cleverer than I actually was.

So, how amazed was I that Anna K has shown me the fun side to Leo T? He is slyly hilarious. How did I not know this?

Please note that I haven't read this novel in Russian Cyrillic. I acknowledge that my perception owes a great deal to the amazing interpretive work of the translators, but let's imagine that we in the West have enjoyed his work as the great man intended.

The title is something of a misnomer and doesn't do justice to an endearing love story that also captures the disparity between city and country life in 19th-century Russia.

For a start, Anna K isn't the star of the show. That billing falls to our anti-hero, Konstantin Dmitrich Levin, a socially awkward, highly-intelligent loner who considers himself to be an ugly fellow with no redeemable qualities.

Despite being weighed down by all this existential angst, he worships Kitty Shcherbatskaya, an attractive young princess whom he believes to be out of his league.

Kitty is described as being "as easy to find in a crowd as a rose among nettles."

Tolstoy goes to great lengths to make us understand the inner workings of Levin's mind (For Tolstoy, read Levin: they are one and the same).

Levin's love rival, raffishly handsome Count Vronsky, couldn't be more dissimilar. He is socially adept and careful not to offend, whereas Levin could probably start an argument with a goldfish.

What a fabulous read this is.

Tolstoy's levity and perspicacity shines from every page and the badinage between the main characters is exquisitely observed.

He does though have an idiosyncratic way of writing: adjectives are thickly laid on with a trowel and he loves to use repetition to emphasise a point.

Anna herself is fascinating, and to affirm just how fascinating she is, Tolstoy employs the word fascinating seven times in one paragraph! Look! I've even started doing it myself! How fascinating!

When not beating you about the head with repetition, the Russian master can do majestic descriptive imagery as good as anyone. One simple scene, where Kitty collapses into a low chair, her ball gown rising about her like a cloud, was just perfectly captured.

This is a wonderful story of fated love and aristocratic hypocrisy.

Tolstoy uses Levin as his political mouthpiece to rail against the ills of late 19th-century Russia, and the author's philosophy of non-violent pacifism also had a direct influence on none other than Mahatma Gandi.

Anna Karenina is often cited as 'one of the best books ever written'.

So who am I to disagree? -

I don’t know where to start...I guess at the beginning. “All happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” -Leo Tolstoy

Exactly one month ago, scared out of my mind, I opened up this book and read that first line. After that it was all over for me because I was completely HOOKED!!! I had to fight with myself about putting the book down so I could get enough sleep. I brought it with me everywhere in case there was a spare moment when I could escape into its pages. This is one of the most truly remarkable stories I’ve ever read, and I’ve read a great many books!!

Going in, I knew that this story would mainly be about two characters, Anna (of course) and Levin. I went in thinking that Anna’s tragical tale of woe would be my preferred point of view. I also knew that there were chapters dedicated to Levin’s agricultural pursuits, and I honestly thought that they would bore me and slow down my reading pace. Oh how wrong past Carolyn was!! The exact opposite happened, Levin’s storyline was the one that captured my heart, as well as his precious love for mowing fields with a scythe. Everytime I read about Levin my heart would melt into a great big puddle. His aspirations for simply wanting to be with the one woman he loves, and living as a humble farmer just made me feel and fall for him all at the same time. Watching his character development from the beginning of the book to the end was incredibly moving and brilliantly written. Reading this story felt like watching a gifted musician compose a grand symphony.

Anna, oh my poor Anna! My feelings and sympathies towards her tended to fluctuate while I read. In the beginning, I felt sorrow for her being in a loveless marriage. Then, when love did come walking in, he brought her inevitable fate along with him. I wanted her and Vronsky to be happy together and for them to take pride in their love for eachother. The slow and sad progression of their bond was something that I thought about deeply. Their choices towards the children involved left me feeling quite uneasy. The more I read the more tension I felt coming off the pages. This all culminated in the very prolific “train scene.” Ironically, I read the train scene riding the train myself, on my way back to NYC. As I read about the approaching train, my own train’s wheels were squeaking and the car itself started rocking. I was completely and utterly transported into the story, while being elevated by my own surroundings. I had to stop reading and collect myself because I could feel my face growing red and my eyes start to water. It was a reading experience I will never forget. To read that exact scene on a train myself was indescribable. That’s when I really knew that this book was unlike any other I’ve ever read. I could feel every word, sensation, noise, and breath while reading, not only that scene, but all of them. Anna’s fate although heartbreaking was raw and honest, and I don’t think this book would have remained one of the most profound books ever written if her destiny was changed.

Along with our two brilliantly written main characters, the way each character’s story weaved together felt like watching someone hand weave silk threads into a beautiful piece of fabric. Each page felt like a gift that I never wanted to stop opening. The amount of times I read a particular line and was then entirely moved is innumerable. It felt like Tolstoy put his whole heart into each and every line. One of my absolute favorite lines is from the point of view of Levin (of course), “He tried not to look long at her, as if she were the sun, yet he saw her, like the sun, even without looking.” *insert crying noises here*

Anne Karenina has become one of (if not) my favorite classics ever. It is tied neck and neck with Jane Eyre for first place, but it is so hard to say. It’s impossible to compare books because each one is different from the other, and that’s what makes this thing called reading so much fun!!

I have so much more to say, but I don’t think any configuration of words will ever fully articulate how much I love and adore this book. The fact that this story is over makes me feel quite empty inside, which was half the reason why I practically cried my eye’s out when I read the final page. Yet, the most uplifting aspect of a well written story, is that once the author and their characters make their way inside your heart, there they will remain. -

Not since I read The Brothers Karamazov have I felt as directly involved in characters' worlds and minds. Fascinating.

I was hooked on Anna Karenina from the opening section when I realized that Tolstoy was brilliantly portraying characters' thoughts and motivations in all of their contradictory, complex truth. However, Tolstoy's skill is not just in characterization--though he is the master of that art. His prose invokes such passion. There were parts of the book that took my breath because I realized that what I was reading was pure feeling: when we realize that Anna is no longer pushing Vronsky away, when Levin proposes to Kitty, and later when Levin thinks about death. The book effectively threw a shroud over me and sucked me in--I almost missed my train stop a couple of times.

That being said, there were some parts that were difficult to get through. I felt myself slowing down in Part VI. I was back in through the remainder of the book once I hit Part VII, but I understand how the deep dive into politics and farming can be off-putting. Still, in those chapters Tolstoy's characters are interacting, and it's incredible to see them speak and respond to one another. It's not only worth the trouble, but deep down, it's no trouble at all. It's to be savored, and sometimes we must be forced to slow down and think about the characters' daily life as they navigate around in their relationships.

A word about this translation. When I was in college I attempted to read the Constance Garnett translation. I didn't stop because it was awful (I think finals came up, then the holidays, then more classes, etc.). However, I never really felt like the words were as powerful as they should have been. Years later, the only image that stuck in my mind was of Levin meeting Kitty at the ice skating rink. I just never really entered the world of Anna Karenina, perhaps my fault more than anything. However, the diction and sentence construction in Pevear and Volokhonsky's translation is poetic and justifies the title "masterpiece." Through this translation I grew to appreciate Tolstoy not just because he told good, philosophical stories, but because he could do so with utmost subtletly and compactness--yes, I think Tolstoy is concise. Each word has its place.

Understandably, many are unwilling to give themselves to this book. Many expect it to do all of the work. But it's an even better read because if the reader works, the experience of reading this book is incredible. -

Tolstoy draws a portrait of three marriages or relationships that could not be more different. Anna Karenina is rightly called a masterpiece. Moreover Tolstoy does not spare on social socialism and describes the beginnings of communism, deals with such existential themes as birth and death and the meaning of life.

Tolstoy’s narrative art and his narrative charm are at the highest level. He also seems like a close observer of human passions, feelings and emotions.

All in all I was touched by his book because it was one of the most impressive books I have ever read.

"Kendi yüceliğinin yüksekliğinden bana bakmasına bayılıyorum". Sayf 55

"Belki de sahip Olduğum şeylere sevindiğim, sahip olmadıklarıma da üzülmediğim için mutluyum."

Sayf 167

"Kadın dediğin öyle bir yaratık ki istediğin kadar incele, gene de hiç bilmediğin yanlarıyla karşılaşıyorsun..."

Sayf 168

"Insana akıl, onu huzursuz eden şeylerden kurtulması için verilmiştir."

Sayf. 758 -

A few months ago I read Anna in the Tropics, a Pulitzer winning drama by Nilo Cruz. Set in 1920s Florida, a lector arrives at a cigar factory to read daily installments of Anna Karenina to the workers there. Although the play takes place in summer, the characters enjoyed their journey to Russia as they were captivated by the story. Even though it is approaching summer where I live as well, I decided to embark on my own journey through Leo Tolstoy's classic nineteenth century classic novel. Although titled Anna Karenina after one of the novel's principle characters, this long classic is considered Tolstoy's first 'real' novel and his take on a modernizing country and on people's lives within it.

The novel begins as Anna Karenina arrives in Moscow from Petersburg to help her brother and sister-in-law settle a domestic dispute. Members of Russia's privileged class, Darya "Dolly" Alexandrovna discovers that her husband Stepan Arkadyich "Stiva" Oblonsky has engaged in an affair with one of their maids. Affairs being a long unspoken of part of upper class life, Dolly desires to leave her husband along with their five children. Anna pleads with Dolly to reconcile, and the couple live a long, if not tenuous, marriage, overlooking each other's glaring faults. While settling her brother's marriage, Anna is reminded of her own unhappy marriage, setting the stage for a drama that lasts the duration of the novel.

Tolstoy sets the novel in eight parts and short chapters with three main story lines, allowing for his readers to move quickly through the plot. In addition to Stiva and Dolly, Tolstoy introduces in part one Dolly's sister Kitty Shcherbatsky, a young woman of marriageable age who is forced to choose between Count Vronsky and Konstantin Dmitrich Levin. At a ball in Kitty's honor, Vronsky is smitten with Anna, temporarily breaking Kitty's heart. Even though Levin loves Kitty with his whole heart, Kitty refuses his offer in favor of Vronsky, and falls into a deep depression. Levin, seeing the one love of his life reject him, vows to never marry.

Anna becomes a fallen woman and rejects her husband in favor of Vronsky, fathering his child, leaving behind the son she loves. Even those closest to her, including family members, are appalled. A G-D fearing woman in a religious society is supposed to view marriage as sacred. Yet, Anna does not value her loved ones' advice and chooses to live with Vronsky. Despite a comfortable, upper class life, Anna is in constant internal turmoil. Spurned by a society that clings to its institutions as marriage and the church, Anna chooses love yet isolation from all but Vronsky and their daughter. Her ex-husband is viewed as a strict adherent to the law, cold, and unsympathetic, and will not grant a divorce. Even though Anna is clearly in the wrong, Tolstoy has his readers sympathizing with her situation, rooting for a positive outcome. He brings to light the plight of lack of women's rights, especially in regard to divorce, and has one hoping that Russia changes her ways as she modernizes.

If Anna's situation sheds light on the worst of Russian society and Dolly's reveals its stagnation, then Kitty, who later marries Levin, shows how the country begins to modernize. Kostya and Kitty marry for love, rather than gains in society. Believed by many to be Tolstoy's alter ego, Levin is an estate farmer who is well aware of the rights of his tenant farmers called muzhiks. Along with his brother Sergei Ivanovich, Levin works toward agrarian reform. Both men, Sergei Ivanovich especially, is swept up in the communist ideals that are beginning to form, in rejection of the tsarist governing of the country. Tolstoy diverges pages at a time to farming reforms and one can see in these pages his own beliefs for the future of Russia in the late 19th century.

Through the three principle couples: Stiva and Dolly, Vronsky and Anna, and Levin and Kitty, Tolstoy presents the old, changing, and new Russia. Having Levin introduce farming mechanisms from the west and Vronsky participate in a Slavic war, Tolstoy presents a Russia that is no longer completely isolated. He reveals how communism begins to shape up as farmers are no longer happy as tenants and many privileged classes adhere to newer values. Meanwhile, through Dolly, Anna, and Kitty, Tolstoy also presents how a woman's role in this society changes, including schooling and her place in a marriage. As the twentieth century nears, Russian life is no longer set in antiquated ways.

Had I not read a drama set in the tropics, I most likely would not have journeyed to 19th century Russia. I enjoyed learning about Leo Tolstoy's views on life there and how he saw late 19th century Russia as a changing society. I found the plight his title character depressing while reading about Levin and Kitty to be uplifting as Russia moves toward the future. Tolstoy's words are accessible in spite of the novel's length, a testament to the stellar translation done by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. A true classic, I enjoyed my time with the characters in Anna Karenina, and rate Tolstoy's premier novel 5 shining stars. -

Alright, I'm going to do my best not to put any spoilers out here, but it will be kind of tough with this book. I should probably start by saying that this book was possibly the best thing I have ever read.

It was my first Tolstoy to read, and the defining thing that separated what he wrote from anything else that I've read is his characters. His characters are unbelievably complex. The edition of this book that I read was over 900 pages, so he has some time to do it. His characters aren't static, but neither are they in some kind of transition from A to B throughout the book. They are each inconsistent in strikingly real ways. They think things and then change their minds. They believe something and then lose faith in it. Their opinions of each other are always swirling. They attempt to act in ways that align with something they want, but they must revert back to who they are. But who a character is is a function of many things, some innate and some external and some whimsical and moody.

So all the characters seem too complex to be characters in a book. It's as if no one could write a character that could be so contradictory and incoherent and still make them believable, so no one would try to write a character like Anna Karenina. But people are that complex, and they are incoherent and that's what makes Tolstoy's characters so real. Their understandings of each other and themselves are as incoherent as mine of those around me and myself.

One of the ways that Tolstoy achieves this is through incredible detail to non-verbal communication. He is always describing the characters movements, expressions, or postures in such a way that you subtly learn their thoughts.

He does an amazing job in the internal monologues the characters experience. You frequently hear a character reason with himself and reveal his thoughts or who he is to you in some way, and all the while you feel like you already knew that they felt that or were that. Even as the characters are inconsistent. There are times when he can describe actions that have major implications on the plot with blunt and simple words and it still felt rich because the characters are so full.

The book takes on love, marriage, adultery, faith, selfishness, death, desire/attraction, happiness. It also speaks interestingly on social classes or classism. He also addresses the clash between the pursuit of individual desires and social obligations/restraints. There is just so much to wrestle with here.

And you go through a myriad set of emotions and impressions of the characters as you read. At times you can love or hate or adore a character. You can be ashamed of or ashamed for or reviled by or anxious with or surprised by a character. And you feel this way about each of them at points. But it isn't at all a roller coaster ride of emotion. It's fluid and natural and makes sense.

One of the many points that the book seemed to reach to me was the strength and power of love. Tolstoy displays it in all its power and all its inability. In the end love is not sufficient enough to sustain. He writes tremendous triumphs for it, and then he writes the months after when the reality of human failings set in. But love is good, and there is hope. Life can be better with love in it. Should I have kids one day I think I'll make reading this book a precondition for them to start dating (that and turning 25).

I was also surprised by a section towards the end of the book where Tolstoy through Levin, my favorite character and the one that I identified with the most, makes a case for Christianity that was so simple but at the same time really impacted me. I guess I'll leave that alone here.

Basically, I don't have high enough praise for this book. I hope everyone reads it. It is very long, and I found the third quarter or so slow. But I could definitely read it again. Not soon but it could become a must read every 15 years or so for me. Between he nature of the content and the quality of the words, I would say that this is the greatest masterpiece in words that I've ever found. -

Another classic in the books!

I have to say, Anna Karenina is the most spoiled book I have ever encountered. I was not surprised by the ending because I have seen dozens of books, movies, etc. where the climax of this book is discussed with reckless abandon. If this book has not been spoiled for you yet, and if your luck is anything like mine, read it soon!

Russian names:

Have you read any Russian authors before? If so, you know that not only are names repeated over and over, they are also often said in totality and they have several variations – some of which are nothing like each other. Because of this, if you try this one, get ready for lots of names and possible confusion over which character is being discussed. But, don’t worry! In general, the key players are easy to follow.

Russian politics and labor:

While this large tome has lots of story, it also has a lot of discussion on Russian politics and the labor climate at the time it was written. This could prove to be either interesting for you or boring depending on what you are looking for in a book. I did not mind it much; it did not end up being my favorite part of the book, but I do think it added a lot to the atmosphere and setting.

The role of Women:

Overall, I was left with the impression that during the time this was written, women were treated very unfairly in Russia (and, I am sure, all around the world). No matter what happened or who was at fault, a woman paid the price. I know this still goes on today with women being considered “sluts” if they sleep around, but men are considered “studs”. Shows that in some respects we have not advanced very much as a society! If a story based on unequal treatment based on gender interests you, this is a good one to read and analyze.

Overall impression:

I enjoyed this book a lot. I have seen many fawn over it as some of the greatest literature ever. I don’t feel like I was quite that enamored with it, but it was an enjoyable, easy to read, follow, and appreciate. I am very glad I took the time to read this classic and if you are looking to take on a big, famous book, this one would not be a bad choice. -

Levin (which is what the title should be, since he is the main character, the real hero and the focus of the book!) (But who would read the book with that title, I know!)

If you don't want to know the ending, don't read this review, though I won't actually talk about what happens to Anna specifically, something I knew 40 years ago without even reading the book. I didn't read the book to find out what happens to her. I knew that. Probably many of you know or knew the ending before reading the book. And this isn't so much a review as a personal reflection. I was tempted, finally, after decades of NOT reading it, to now, approaching my 60th birthday, finish it, all 818 pages, tempted to just simply write: Pretty good! :) But I resist that impulse, sorry (because now, if you so choose to read on, you will have to read many more than those two words. . .).

This is as millions of people have observed over the past 140 years, a really great book, and those of you who are skeptical of reading "Great Books" or "classics" may still not be convinced, but this has in my opinion a deserved reputation of one of the great works of all time, and one of the reasons it IS so good is because it speaks humbly and eloquently against pomposity and perceived or received notions of "greatness." Why do I care about its place in the canon? I guess I really don't. I just think some books deserve the rep they get from the literary establishment, and some deserve the rep they get from the wider reading public. This one is a great literary accomplishment AND a great read, in my opinion, and deserves to be read and read widely by more than just the English major club. And I say this as one who prefers Dostoevsky to Tolstoy; I seem to prefer stories of anguish and doubt to stories of affirmation and faith, and the atheist/agnostic literary club I belong to is maybe always going to favor doubt and anguish over faith and hope and happiness. But to make clear: This surely is a book of faith, of family, of affirmation, of belief in the land, nature, goodness, and simple human joys over the life of "society" with all of its pretension. Yes, all that affirmation is true of the book in spite of what happens to Anna.